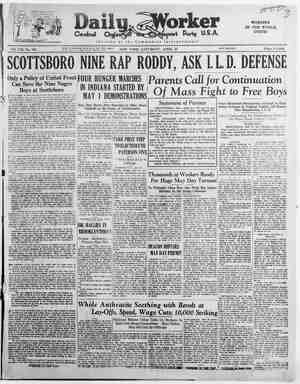

The Daily Worker Newspaper, April 25, 1931, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

RE Bch onan ¢ VALENTINE VY. KONIN ing himself shouted s hands. him the asked sceptic: each other pected, eay From across greeted the Bol: shower of thundering bo throughout the night, the two tc buried in the grave of Carpa Valley, roared and sh shocks of the exp ‘The next d tablished | a h the about t Ing inven locking up tt with them leafle the ydistributed working elements of the town. Before | long, half of our youth in town join- ed the Communist Party. Vaska, the bookbinder’s apprentive, began to call: himself Comrade Cher. noff, and took tl around rich peop! ops. They brought and posters which and went to villages to, §) peasant women. The shop keepers in town feared her. The intellectuals snickered at her and called her “Sec- ond Jeanne d’Arc.” For the first time in our town, things began to | look as if something were going to happen. Town Bustles With May Day Plans At the end of April, when the| brown of Carpathian Mountains be- | gan to curl with soft, lemon colored down the city at the foot of the east- ern mountain was bustling with | preparations for May Day. The for- mer Alexander Square, opening up| towards the river, so that one could | look across until the Rumanian | mountain shut off the sky, was dec- | orated with posters and festoo: ‘There was to be a march and a dem- onstration of the workers in honor | of the International Workers holid All this was new in our town, but ‘was received with great enthusiasm. The center of attraction on the square Was @ huge wooden collonade, lit up by electric bulbs, declaiming in gigantic red letters a revolutionary | thyme: “In spite of bosses’ hate and ire, “We'll spread the flames of world fire. “Just ake @ look at that,” said Stepan Mikhailovitch Ogonov, the the former director of Boys’ Gym- nasia, passing by the square with aj friend of his, a former banker. “They are forgetting that one can eas see across the river. Rumanians will never allow the demonstration to take place.” Kolka, the former bootblack, who ‘vas puffing under the weight of a huge poster, heard the remark and raised his head. “We are forgetting nothing, com- lavishly among the | he said d with in- but his idged him red enr- a member wadays a than a Crowd Marches to Meeting Place ched into the Alexander had been cool ‘ble ue, and ‘the river quivering | wrinkles. In the orchards, pink blossoms, Is fell like snow ust of the un- red posters, peop! ts into the square, ar sxpectantly around the de- over the peak of a blue cloud, chip of marble, to float over the firmament. by the western wind, it spread | the air, and the leaves acacia trees swished e wild currents of the wind. le Gornostaiev, with a red his khaki uniform, climbed of statue. T tre- f hand clapping an- is greetnig. He straightened led down his jacket, and be- to speak. Rain, Water and Powder A heavy drop of rain fell on the ground with a soft thud. The crowd, | e, turned up their heads to- | A lavender zigzag | x ‘ore through the cloud, a to! ent of round drops burst | The crowd joyfully, | thirstily the fresh smell ly shouted to Com- y, who stopped for o “We are not Comrade Gornostiev in. parees inced another word, two peals But prono! of thunder—one from the sky, the} other from across the river, roared together in freightful dissonance. A g bomb burst into fragments behind the statue, hurling up a foun- tain of earth and stones. MAY DAY OS of the gloom and the grim,/} bitter fight Rising to greet thee, O first of May| Toilers and slaves we emerge from the night To hail the Red Dawn of the work- ingman’s Rese ck ae Songs of our fury ring through the air | Reckless and fearless our rebel re- frain. Strong in our numbers, if we but dare We shall our freedom and liberty gain er wey Remember our comrades the masters | have slain When loud in the struggle their voices were heard. . | Remember their hours of torture and pain | Because they blieved in the workers— the “herd.” ee es | Songs of the struggle thrill us today Songs of protest, of defiance, of hope. | Ours is the laughter born of the fray | Scornful of masters and of their yoke. | * We hear the red thunder in China. proclaim The Soviet surge of the people in chains The Red Armies marching and feed- ing the flame That, yet shall consume the lords and their gains. eee ieee | Songs proletarian sung by the workers Songs of rebellion, of vengeance, of hate Death to the parasites and all the shirkers All power and life to the toilers’ estate! ON THE BREADLINE By AL DASCH , STAND on the breadline; it is raining and very cold. I draw my thin and tattered overcoat closer! ‘that is called soup which acts upon your stomach as if it were a acid. igs TI leave the line and the rain, but if I did, my lost and what is rai) uld be delayed an All along the line I umbling of the sullen waiting for something to appease their hunger. I listen in to some of their remarks and I grow} “Damn it! What the hell are we gonna do?” Shea getting desperate. I'm gonna do something soon if things don't! | "Ys this whet I went over for in. "18? Well, my know what to do next tim I get me milits on 2 oun.” Tye betteweeking °0 years Jook what I've got now.” ip me and A “Something's wrong with this coun- try, fellows, and we gotta do some- thing for ourselves, because the rich ain't gonna do it for us.” Suddenly the law appears. “Cut out that beefing you guys or we'll throw you the hell out of here.” I look up and see the beefy, a florid face of One of New York's finest. He is tall and big and strong, such as I was once myself. In direct contrast to my gauntness I see his bay-window protruding through the folds of his large and comfortable slcker. A great and overpowering rage wells up in my heart, as I gaze upon thie minion of the bosses. If I could only hurl myself 25 this brutal beast whe serves and protects those who are re- sponsible for the degredation of thc workers. Little chills run up anc down my spine and my scalp begins to itch, I feel that I am working my- j sel f into a frenzy of excitement. My , dull for months, I know are gleaming Tam tense and aflamc with emotion, I must let somethine loose or T burst; but—I control my- self. The time is not. yet ripe. But, our day will come soon so that we can shake off our chains and shackle: and emerge free men atu workers ~not slaves, will be | toon of May ist, a huge f igh and spot- | Dressed in red shirts, | Alexander II. | st of the road began | | ‘The crowd turned into a stormy sea of heads. In insane panic, people crushed each other, running over fallen bodies, yelling with pain and freight. With a prolonged, deafen- | ing whistle, another bomb shattered the remains of the statue and threw up into the air a mass of stones and human flesh, Sobs and shrieks were lost in the sound of bursting bombs, and the hard steady pouring of the first thunderstorm of the year. Once more throughout the night | the twin mountains glowered at the flaming bombs flying across the river. In the mornin gthe warfare ceased, and the risen sun lighten up with joyful brilliancy the green of the re- freshed forests, | Prepare for Vengeance Alexander square was a pitiful sight. Human bodies, piles of stone and earth, and hardened fragments | of shrapnel, were scattered on the ground in choatic disorder. The | soaked posters and festoons hung | from the tree branches in curling | shreds. Over the glistening smooth- ness of the grass, raindrops were | trembling like tears. But strangely | enough, one half of the oollonade was | still standing, and dancing in the | waves of the wind, the red letters glared challengingly across the river: “In spite of bosses’ hate and ire, “We'll spread the flames of world fire.” “Those sober virtuosi of Protestant- ism, the Puritans of New England, in | 1703, by decrees of their assembly set |a premium of $200 on every Indian scalp and every captured red-skin; in 1720 a premium of $500 on every scalp; in 1744, after Massachusetts- | Bay had proclaimed a certain tribe ce rebels, the following prices: for a male scalp of 12 years and upwards, $500 (new currency) ; for a male pris- | oner, $525; for women and children | prisoners, $250; for scalps of women and children, $250. Some decades | later. ..at English instigation and | | for English pay they were toma- | | hawked by red-skins.”—Marx: Capi- | tal, Vol. I, p. 825. Last year thousands of workers downed tools on the workers’ holiday. Moscow, New York, Chicago Buenos Aires, Madrid, and Shanghai. \ Toiiers marched in Berlin, Every indication shows that this year’s May Day demonstrations will be even larger and mightier than the preceding year. By ALBERT MORALES, Dressed in shorts and a sleeveless blouse, he was sitting in the doorway | of the blue, plastered, one-room house | looking from the ground to the hand- | mado ladder leading to the railway | emhankment, up to the sky of stars multiplying in number and brightness |as the Hot day faded. From the embankment came a pro- |cession of greetings: Goodnight, handsome youth! You're alright down there, aren’t you? Till tomorrow, little brother! He answered all of them, exchang- ing quick jokes with those who were not 60 tired. ‘The long line of people—consist- ing mostly of brown-skinned women wearing colorful blouses and skirts spe to their bare feet, and carry- jing empty baskets on their heads— was like a multicolored serpent grace- fully gliding homeward. From the opposite direction, where |the railroad bridge crosses the river that divides this tropical Mexican village into almost two equal parts, appeared a group of young peasants, | dressed in clean white muslin shirts and trousers, and dragging long pieces of sugar cane with them. Amid spicy remarks almost sung at them by the younger women, they managed to get to the left side of the embankment and walk along single file. “Romulo—.” Four of them sprang lightly down the ladder to talk to him. “We have to see you, about plans for the May First demonstration. You know—strong language, like the work- jers in the oil fields use .. . lixe you j Were telling us. Now first of all, we |are going to protest against the. gov- ernment’s attempts to disarm us, against their refusal to give us more Jand—” “Come back here tonight, It will be better,no? We'll go over the ques- tion well.” “That's fine, comrade. Here’s some sugar cane for you and Auria. So your love will never be anything but sweet—” They left, going along the foot of the embankment past little blue, pink and yellow houses with red-tiled roofs, to the corner where the street is on a level with the railwaytracks and where the other i were waiting for them. Romulo pretended not to see her coming from the river near-by. Slowly he rose and caried the chair inside. He was standing close to the deep yellow hammock suspended be- tween two walls when suddenly he felt her head of damp laid against the back of his neck. From over one shoulder, he watched her large black eyes, brillant as the stars outside. She gave his raised shoulder a hard push; he lost his balance and fell into two strong arms, Laughter like tropical rain dispelling the vapor rising from the hot soil. “I have to get up at dawn, Romulo, and go out with the Jimenez’ to pick flowers for the church festival.” “It's about time you left all that, to the poor old women—well, you etter stay at the Jimenez’ tonight, decause T have a meeting here tonight with some peasant comrades. We may be up pretty late.” “No I'll stay. It’s too late to go over there now. We'll put the table “seinst the wall there, so the ham- “ook won't be in your way... That's ond, Well. let me prepare gmner, diy youth, Don't you want to light a ca coal ashes?” | “Just give the ashes one of those | tender glances, Auria, to make them | flare up like the midday sun—” As she began to awake, tobacco smoke and the light from a dying | candle irritated her half-opened eyes. The tobacco smoke was everywhere. With the hammock strands pressing against her nose, she watched it hazily, gliding in thin waves over the dark brick floor, spiralling leisurely up the white walls. Through one eye le while I fan the char- jshe saw the wooden door, shut fast; jfrom the left side pf the room came | the sound of whispering voices grad- ually getting clearer.’ Her clothes | jand body were damp with perspira- tion. Sleepily she shifted to her right | side. Through the hammock, the back | He | was sitting at the table surrounded | Sheets | of Romulo’s head was visiblé, by the four young peasants. of paper littered the small low table. Words and phrases broke against her |.. Sleepy senses like clean white surf on @ deserted shore at night. TROPICAL AWAKENING | “Fight ... against this crisis caused by capitalism . .. May First demon- stration . . . must be . . . militant fight ... against unemployment... Protest against government ... fas- cist labor code... trying to sell work- ing masses into slavery .. . to foreign imperialists . . . and national bour- geois agents . . . workers, peasants, and soldiers . . . must unite . . .Peas- ants must not surrender . . their arms + Protest against government white terror . . . against the massacre of revolutionary . . . workers and peas- ants—” Ghosts of Sherman’s Army By ALLAN JOHNSON | I tried the impossible task of mak- | ing myself comfortable while we, were speeding across the Louisiana flat- lands at 65 miles an hour. |I thought of how far-reaching the influence of the Party had become. |Capitalists in far-away Texas, an empire as large as Germany and just as remote in the minds of most Americans, had become so fearful of the Party’s in- fluence among the exploited workers in the state that they had resorted to kidnappping two of the Party’s or- ganizers, That ride through Louisiana has burned itself on my memory. The state was utterly desolate. It was as if the ghosts of Sherman's army were still on that mad rampage that had started in Atlanta and had ended in the violent birth of the Ku Klux Klan. Weatherbeaten houses buckling in the middle, barns on the verge of immi- nent collapse, fences long out of re- | pair, tattered clothing poorly dis- guising the thin shanks of the starved-looking farmers. Mules so emaciated that they dragged them- selves around as if weights were at~ tached to their legs...what but a conquering army could have left a land so poverty-stricken? It was an army, in fact, which had overrun the land, but it wasn’t Sherman's army. Dallas in its half-mile of business section has a dozen slim skyscrapers, as many broad-windowed depart- ment stores, and two or three hun- dred expensive looking shops. Here the] resmblance to a metropolitan city ends. Under the nose of Dallas’ busiest street lies. “Little Mexico,” where 6,000 Mexican workers live in the direst poverty in tumbledown shacks flanking dirty yellow mud streets. As many as 20 Mexican workers are forced to sleep in a common bedroom. Adjoining the business section lay the Negro workers’ homes. The Ne- “Little Mexico.” »Stark, brutal poy- erty enfolds both districts like a shroud over a huge grave. The white workers in Dallas are somewhat bet- ter off than their Negro and Mexi- can fellow-workers, but still it is al- most impossible to walk a hundred yards without being asked for a handout by two or three white work- ers. I met up with a comrade. He was @ native Dallasite, a youngster of 20 who had joined the Party two months before. Members of the Klan were following him, evidently wait- ing for him to lead them. to a meet- ing of the Party comrades, and we home to shake the vultures off. The home was as bare and as clean as a pin. He introduced me to his mother, @ careworn, stoical woman who suc- cessfully hid any fear that she might have had for her son's safety. After speaking to her for a moment, we went into a room facing the street. Sitting in a cane rocker was the boy’s father, a man of bout 60, with @ shotgun across his knees. He eyed introduction, “Tm not a Communist,” he sald, “Tm too old for that, You need young ones in the Party. I can’t do very much, but I've got plenty of buckshot in the house for those bas- tard Kluxers if they come here look- ing for trouble. I wish I hat my chance all over again. I've voted and campaigned for every faker in the something forthe workingman— Cleveland, Bryan, Roosevelt, La Fol- lette...all of them, even the local ones. T know now that the issue can’. be avoided. We'll have to turn to our guns sometime. I hope it’s soon —under the leadership of the Com- munists. I* hope I'm alive...well, we're accustomed to guns in the south. “It's hard for a Southern white | man to get used to the idea of treat- ing a nigger equally, An empty belly sort of changes your mind, though. We hd 4,000 in the February 25th demonstration; 3000, niggers and 1,000 whites. I never thought I'd live to see the day when whites and niggers would get together like that. You don't mind my calling them niggers, son, and not Negroes? It’s hard for an old man to change his tongue." had to take a roundabout way to his | past 40 years who promised to do’ gro quarter varies but little from|:°- | me suspiciously, in spite of his son’s|** [fighting cold tears. .", She could feel the perspiration gathering on her forehead and up- per lip. The room was a boiler. Steam in the form of tobacco smoke was coming from the little table . . from the young worker and peasants standing around him .. with one bare leg she was instinctively pushing against the floor to sway the ham- mock, “... at Jimenez’... by dawn flowers for festival...” With her foot touching the dark brick floor, she fell asleep again. “I hope he brings some coffee with the buns—” Voices that semed to be laughing. “Watch—he’s been gone only a few minutes, but he'll come back with a whole history—” Warm air was coming through the slightly open door, and the room was even hotter than before. She heard Romulo speaking in a low voice. “Remember, comrades, these resolu- tions must be gotter. to the district headquarters at once; to be mimeo- graphed and copies sent out immed- iately to all locals. Remember, in case the original you have is taken, there is a copy up there—” Up there? Auria opened her eyes. Romulo's profile was smiling at the framed photograph of herself dressed in the classic native peasant dress. It happened very quickly. The laughing young peasant entered hold- ing an armful of sweet buns. “There was a fellow near the river with a bouncing, squeeling pig on his back; he saw me and started running, like a buzzard over the sand . .. like this + well, everyone has his own strug- gle for a living—.” ‘The door was pushed open violently; sweet buns went scattering over the floor. Star- ing through the hammock, dazed from sleep, her wide-opened eyes saw the room as a whirlpool of tropical helmets. Silent armed soldiers: A young captain’s rapid commands. Still half asleep, she was rushing after them as if in a dream. The night, soaked in perspiration and tears, Peasant feet over the ground, Dogs barking around the shoes of silent marching soldiers, A peasant girl’s skirt ruffling the soft tops of sleepy littie shrubs. The warm droning of a distant, water pump. The beating of a frightened heart. Seated on a rock near the military barracks where they had been taken, she felt a thought struggling against her memory. Something she must do. Sleep drummed at her senses. The gray dawn was spreading thru the foliage. Flowers for the festival. No. Something Romulo would indi- cate, Sleep pressed against her eyes. A smiling profile. Up there. There— the photograph . . . Of course, be- tween it and the frame. “. . .must ‘be gotten to the district headquarters at once . . . copies to be sent out im- mediately to all locals.” Sleep « « protest against ... the massacre ... of revo- lutionary workers and peasants.” ~ "| hand. Fish Scales-May Ist! cas By DAVE HOROWITZ May Day, 1930, The workers of the world on the march. Metal work- ers, textile workers, marine worsers, office workers, and food workers hailing the spring of Freedom with red songs, red banners, placardy of defiance of militant labor against the Tuling classes. Workers of Europe, in Germany, ‘England, France —all against the terrorisms of old world capitalism. Workers of Asia, in China, Japan, India—against tmpe- rialism and its horrors of super-ex- ploitation. Workers in the Latin Americas—against the blood sucking tyrants of Wall Street. Lands of Boss Luxury. May Day in America, land of capi- tlist prosperity and mass poverty ana misery, to the far north and south, labor breathing the distant alr or Freedom from the land of the So- viets. May Day in a little room on Ave- nue C in New York. Jacob Bordan- sky, fish worker, sitting on-a broken chair, thinking of what society would call, his life. From the ceiling a rope is hanging, limp nd waiting for the victim of capitalist equality. Through the dirty pane of the single window the bright May day sun struggles to light up the squalid shabby room, But the sun alone cannot awaken the spirit of the worker broken on the rack of twenty years of stupia driving toil. The Toiler Tells His Tale. I am that worker, Jacob Bordan- sky, fish worker, forty-five and ready to die. I will speak to my fellow workers of the thoughts that hound- ed me in my last moments, Listen! My parents were killed in a po- grom in Kiev, and I came to America to escape the -oke of the czar and to make money in the land of oppor- tunity. My heart was fuil of hope that here I would find a better life and happiness. A retail fish market owner in Washington Heights gave me my chance “to become rich.” In return for honesty, diligence, and veryhard work, he made me “manager” at the end of five years. My salary was $25 a week for which I opened. the store at 6 am. and swept the floor and coveved it with sawdust. I chopped two full cakes of ice and filled the empty fish bins with it. When the truck came from the market I helped un~- load the barrel and boxes of fish. Then, I filled the bins and assorted fhe fish to look good to the custom- er. At noon I felt tired but a “man- ager” must work hard and besides my. boss would bring me lunch, two rolls, canned salmon and coffee. Then the rush came and my real work starts. The boss would take the order from the customer. He weighed the fish, and talks nice'to her. Then he shoyes the basin of fish to me. The fish are slippery corpses. They must be nailed upon the cleaning ta- ble and I scraped way at the sides until the scales are removed. Scales Are Like Pests. ‘The scales are like mosquitoes in summer. They fly all around. They settle in one’s hair, in the ears, they dart at one’s eyes, down the neck, into one’s clothes—but one gets used to them. Then, for the insides. Slit the belly. Rip out the guts, scrape a the bones until the fish has been stripped of all its matter. The eyes stare at one dully, stupidly, but It is @ fish made to be eaten, one mz a living at it, and so to the next ana the next until the arm ts the fingers swollen with salt and the hands full of cuts and brutses. But. the customers keep coming in, ‘and the fish grow into an endless jungle of sliding bellies and flying scales— and the receptacle under my table is foul with an awful stench, Unti it seems that all the fish in’ the ocean have come to me for the finish, Equality of Opportunity, This was my life in Free America. I wanted education in her. “free” schools, but she gave me no time. for it. She took my energy, my life blood to the last drop while I was dream- ing of wealth and a better life. She doped my mind with Her cheap, jin- goism through her press, her cinema. Before I die I must confess to the one crime of which IT am guilty, - My crime is I believed her. Jacob rose suddenly from his chair and stood upon it to gain the proper height from the floor. He placed the noose about his neck and’ gave the rope an experimental jerk before leaping into nothingness. But before he could do this there was a great uproar from the streets below.'''A trermendous wave of sound that grew stronger and stronger like the noise of a great multitude in an arena, cheering the combatants. What was it? People were cheering, singing, ‘for what? One more look at humans that could be happy in such a world! Jcob threw off the noose walked slowlyl to the window. He opened it and staggere dback from the blinding glow of the brilliant May Day'sun, from the sudden rush of life that leaped up at him from the giant spectacle on the street below. : ‘ Vanguard of Working Class._ I saw a great army of tollers marching together. They waved ted banners, carried huge placards contained a challenge to organized capital. “Down with Capitalissp!” “Down with exploitation!” “That's right! That's good! Down with the masters who drive us Uke staves. Wait, wait for me. Ill be right down.” Solidarity Forever. On the street fifty thousand work- ers marched to the tune of “Sdli- darity Forever.” Every branch of-in- dustry under its trade union banner, Food Workers Union, Needle Work- ers Union, Office Workers, Marine Workers, Metal Workers, Shoe Work- ers, Machinists Unions. “The union makes us strong.” Jacob took his place with the food workers. . “Solidarity forever.” “That's. good. No more alone. There is a place for me. He called me comrade. Com- rade, sure we're all comrades. Where are the fish cleaners?” Jacob didn't find the fish cleaners, but you will see him next year,on May Day holding a banner in his hands. The fish workers branch of the food workers union. For he is spending all his time organizing all the fish cleaners in évery fish store in the city. And you will hear 4 new voice, a strong voide, leading. his comrades in “Solidarity Forever.” By JEANNETTE D. PEARL. ‘We had to stand in line to be ad- mitted to the banquet tendered to Comrade Foster by the workers of Los Angeles. When it came my turn to enter there was a shout from within “no more.” The door was about to close upon me, when my coaxing gaze halted the doorman'’s “Guess we can make room for one more comrade,” he said, his stern face relaxing in greeting me. As the door, closed behind me, I saw two flights of stairs, one following the other, that lead to the large hall of the Workers Cooperative Auditor- ium. On both sides of these stairs and on each step, was stationed a Red Guard, grim and silent. None were armed. Yet it seemed as if each man had a rifle slung over his shoul- ded. I sensed each man knew that something might happen and each stood prepared. My heart began beat- ing fast. This was no dress rehearsal. Its grim reality gripped me. Passing through this flank of invisibly armed Red Guards I had the feeling of the iron heel of our American democracy. Coming into view of the banquet hall, the scene was changed. Here a festive gayety pervaded the hall. Long tables with dazzling white linen cloths stretched across the entire length of the hall which was ablaze with many lights, red floral decorations, and banners. About 1,000 people were massed in the hall, The diners were crowded at the tables while others stood in the isles and against the walls, waiting the arrival.of Comrade Foster—or Commissioner of Police, Greetings were being extended by various delegates, pledging moral and financial support to build the Trade Union Unity League. Lively chatting, smiles and radiant faces, expressed the joy of “this is our day, ours”! Yet beneath the spirit of festivity, one could discern a feeling of apprehen- sion in the intermittant glaces cast at the door, which was to admit the symbol of freedom, Comrade Foster; or the reality of brute force, Police-. man Hynes. Suddenly a commotion, one felt the pressure of hushed breathing as the entire neck of the audience craned at the door. Comrade Foster with a body guard had entered, He stood there in person, unharmed. ‘The re- pression of the evening burst forth in tumultous applause, cheering, stamp- ing and Sie of hands, A raptus’ | Who Would Enter the Door? rous wave swept the audience and their emotions burst into song. ‘They sang the International with all. the fire of their souls. why A seat had been reserved for Com- rade Foster near the door, a tionary measure in the event of a raid or arrest. As honor guest at the table sat the Japanese cont:nde, Hama, with a crown of. white ’ban- duced to speak, the entire audience. tose to its feet and again began cheering amidst thunderous approval circled throughout the Comrade Foster spoke of the Set Comrade Foster pang re gy e intensive force. mendous courage he instills ina audience!” a technical worker|/ob- served. It is precisély this this confidence and pais in the es that endears Comrade ‘Foster to the masses. At the conclusion of the Comrade Ida Rothstein, the man, announced that the those standing were to leave first and her admonition was that each . person go straight homé, Between the two columns’ of ® Guards, we filed out. The silence, the quick way was a foretast ot the determination and hope :for bamgney cious = abe For Next Week~: ‘The Saturday Feature: Page ;will exe childhood in leans oko ers’ childhood in “Mush and Milk,” “No Incentive For. Work,” poems, and several drawings. Have you sent in your contributjons for the Saturday page, tf not wet busy Se Oe er i. ? i