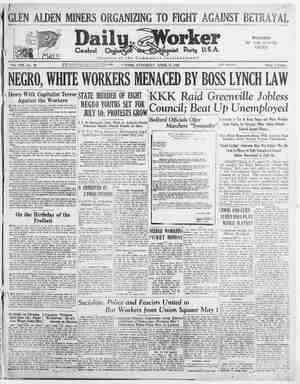

The Daily Worker Newspaper, April 11, 1931, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Page Four “The Holy RECASTLE, a low @ dark hol ricane lamp is ceiling. The f. very sick, and struggling to k flares up an A the table Tread wa light flares. mending shirts, and, co’ ressi fed in the for frightfully quiet. internal heat, and then being longer, he would get up, grit and grapple with whom he would sn ces thus it feel admiring with a sarcastic er old ship Ma riggings that are in the. moonli ter like silver, of a phantom st port and sai. forth — is heard of again A rowboat comir fre bangs against the side of the The ladder clatters as somebody ip, and jumps on deck. ps are heard going f ward, they stop, then turn and enter the forecastle. The hurricane li in shame anguisl brighter, gives a we! reveals a deep-chested sailor who has just entered and the middle of floor brawny arms folded 2 He is about to spe 1 around. Again the light «contrac and then suddenly flushing red as in -shame and anguish, it s hi upon the late comers’ weather bea and-rather handsome face that now bfuised, battered, one eye almost closed. “Well, Olaf, what did the consul tell you?” Anders confronted him. Anders a big, raw-boned Finn in- quiringly looking through his deep set eyes that made a stfange con- trast with his weather-beaten, battle- man the scatred face by virtue of being so} blue, so clear and of such strength and determination rightly to be ad- mired. “Oh, the b—!” exclaimed Olaf. He looked around, his swollen face took a sad expression. “He threw ™e.out,” he began, and after a pause, “What could I do? I told-the consul how the captain had framed an innocent man, thrown him continued: in prison in order to clear himself of | having deliberately, may as well say: thrown the soldier overboard! I also showed the consul our statement, signed by all of us, how the captain is responsible for the death of three of our-shipmates, who were washed overboard when he broached the ship into.the gale. “But the consul simply laughed. He tore up our statement. He did It so coolly, deliberately tearing it into small bits, over and over again, and then he let the small bits fall into the waste basket, like he was play- ing. Again he laughed. I stood and looked, just looked. ‘The consul saw me-and frowned. ‘Get out of here!’ he cried.” I would not go. I still persisted, wanted to tell, explain how the captain-had so unjustly thrown Jim- tiy ip-prison. I wanted him to be swollen and| ~ of us ¥ the voyage nd no f the deep ibdued voice af ok around Rerr r the word. Anyone who with us—is against us. struggle is for life and death.. We shall take no chances. For it is either we or they. There is no middle ground.” Anders fi d, crossed his arms on his chest stood like a statue of a as slight com: body got up silently each other all around. se, horny hands met and clasped | feeling that can only course through And thus the mn and another ship the bl DAY d of workers. Was? S¥ ht ntinued.) NEXT WEEK a Bl smith Shop,” |“On the Breadline,” “Workers’ Life |in Dallas, Te: by Allen Johnson, |“Red. Mother Goose,” by Henry | George Weiss, book reviews, cartoons, drawings, are all scheduled to ap- pear next week. Don't forget to look for them. HAVE YOU DONE YOUR DUTY? Have you done your May Day duty? Have you sent in your feature story, cartoon, or picture for the special May Day issue? HAP JINGLES . Jack and Jill went up the hill, The drought had seared, the lowland; They found the hil! starvation-still, For there the poor had no land. —Drawings by Gropper. Little Jack Horner | Begs on the corner, | Ready to ravage and rob; e's paid in ‘9 the rez Bat they never found bim a job. | | * 2 | not | tor did ni Y| and told stories rmth and a sincerity of | DATLY WORKER, NEW YORK, SATURDAY, APRIL 11, 1931 | The Girl Who Surprised Herself By JOSEPH VOGEL WO girls who worked side by side a dress contractors’ shor mentally as unlike as red and ; but they happened to be good y was a radical Helen her breast the most T ten in bourgeois of bourgeois saspirations Both were strong willed, but Ms | was quiet, serious, whereas Helen was ironic tongue. machines whirred Helen @ continuous stream, whether the boss was behind her or “You listen to me, girls, some day this baby is going to get a fur coat for herself, and a rich guy, and you know what else? You won't catch me working all my life in a dump ‘ike this.” “So this place is a dump, eh?” said boss, upon overhearing her, “Well, | nd you'd give us all fur its for a bonus, wouldn’t you?” said ¢ talk more respectful to your * said her employer, ed away. Helen whi hard luck for us if harder, hor Tll spit in The girls giggled. g the brief lunch hour M: m with her obstreperous about what nerve and tongue to help make ditions better in the shop, to help nize so we can get hig you'd acco 1 somethin: ot only for y for all of us “Oh, you and your revolution,” said Helen mockingly. “Why should I id about other girls? hands full taking care of ‘How foolish!” said Mary. “The boss won't give you alone a ri in e that would ma the when all of ‘h me, kid,” explained Helen. a raise before the end of this ch.” urhed to their machines, to t and render imitation silk into the latest styles from Paris ae | ‘Two months later the rush season t = girls had no time now hile at work. The contrac- hire extra hands, com- plaining that he could not afford to, ness had been so bad all year good luck never hi ned to et.” Helen no longer laughed at the end of the day she could scarcely rise from her “| chair to go home. On the other hand, it was Mary who now talked to the girls at every opportunity. “The boss is spe ig up his machines and he isn't S a cent extra. Don't let him fool us by saying he'll appreciate it if we cut down our lunch hour a few min- utes. If he wants to show any ap- preciation, he can do it in salary.” One day the boss surprised the girls and he m, if you would only use! “See if I don’t make him give] » “You'll simply have to fin- ish up the day’s work, or not, stay | overt: for a few minutes. I can’t wu cand it, but you're so slow these days on the job. What's the trouble with you, don’t you sleep enough? “By the way, how much are you | , Said, imitating her friend's mocking | tones, “Goodbye fur coat.” | “We'll see about that,” answered Helen, bitterly. On the next day when the machines usually became quiet, the contractor | | | | | Mosselpron Factory in | Union, | Louis Lozowick, who is one of the May Day delegates to the Soviet Union organized by the Friends of the Soviet Leningrad, a. Lithograph by \ | going to pay us for overtime?” asked Mary. ‘The contractor looked at her as if he had gone crazy. “How much I'll you for overtime? Listen to me you should be glad to have a job these days, and you. should thank God I don’t cut your wages now that business is 50 ‘bad and I'm losing | hundrdes of dollars a week.” | “Say, how can I work when you make so much noise?” shouted Helen, turning around in her chair. The boss opened his mouth to re- ply, but changed his mind and walked away. “Dou you stil] think you'll get a | raise?” whispered Mary to her friend. | And after several moments, during which she watched Heien's face, she (A Review by HARRISON GEORGE) “No more parties! We are all | Germans and only Germans! Our |Army! The Navy! Hurrah!” These were the cries of the Ger- |man masses on those first days of August, 1914. Between these words which are jot the rarest of war books | Kaiser’s Coolies,” by Theodor Pli- vier) and the last lines of the book, is a tremendously graphic picture of how imperialist war is transformed into civil war. The last lines are “The Emperor's flag was lowered. The Red flag was hoisted. All the ships yielded without a struggle.” No revolutionary worker who wishes to understand the Leninist conception of the transformation of an imperialist war into a civil war can afford to be without this realis- tic picture of the process—we re- peat, the process and not the act— by which such transformation is carried on. Compared to “All Quiet on the Western Front,” by Remarque, “The Kaiser's Coolies” is in every way superior to the book by Remarque, which is only humanist rubbish by comparison, which ignores the masses and magnifies individual characters. Plivier’s book, on the contrary, takes the German masses as a whole, the tremendous significance of the war to these masses, and only upon this basis does he follow the individ- ual characters through the war from its beginning until its revolutionary close. Thus, the whole perspective is altered from an individualistic out- look to @ class outlook. This is the great contribution which Plivier has made particularly to the youth of today who did not see the war, who did not feel the horror of the war, who have not in their experience the perception of how war affects the lives of the toilers and how and why civil war arises out of imperialist. war. Here we see the German mer- | chant sailors taken by force from an jold tramp steamer as it enters a | German port-in the opening days of ven to the opening pages of ene | ©The | announced that the girls would have to work an hour overtime. “Of course you're paying us extra,” said Helen. ; “Are you Leginning with such nen- | sense again?” said the boss sharply See you tomorrow morning.” She walked to the cloak room and ieft. “The next girl who does that. I'l fire on the spot,” shouted the Pointing toward the cloak rom’ he said, “if Helen wasn’t such a good worker I'd fire her tight now. Alright, get to were ...come on!” The girls retur to work, and the contractor continued, “don’t worry, you'll hear something more about this whole business.” The next morning Helen returned to her machine. The boss said noth- boss. “THE KAISER’S COOLIES” jval service, while the bourgeots-in- | fluenced masses feverishly hurrah |for the Emperor! It is the opening strains of the overture which, all unexpectedly to the imperialists, changed three years later into the mutiny of millions of armed men, | the simultaneous uprising of the suf- | (LIAR IN SImtaray ) MNT Te Wor tin iF Teey Fear AIS foe es ‘The Emperor makes a speech of sympathy to the working class. —By Walker. fering working class and the crash- ing tones of the Internationale. Tere s E) This book is tremendously human. Nothing in a sailor's life is omitted, from dipping into the wine cargoes of the old freighter to “short-arm inspection” in the navy. No detail is left out which goes to picture either the hilarity or the hardness of a sailor's life. ‘The characters of the story are brought forward just as they are, whether noble, cowardly, loyal or traitorous to their class. Here we see the bureaucratic officer class and the development of the spirit of mutiny with which the war was ended. In this book, “The Kaiser's Cool- ies,” we see where the common sailor is not only brutalized but robbed by the officer class and sent to instant death by the thousands in order to gratify a military ambition, Here are the first signs of the storm that lis coming, the ribald verses scratched jthe war and dragooned into the na-! on the lavatory doors by the sailors and—audacious trick—on the cap- tain’s door! Sparing nothing, Plivier takes us to the homes of the sailor folk in the German cities, where women with their lungs wasted away and great sores on their bodies from the chemicals in the munition plants, greet the eye, along with the beastly- treated Russian prisoners of war, and every sailor finds that in his home his children are starving, his wife weakening under the terrible hunger and war work and worry. —By JOSEPH VOGEL. | thought of it herself, and she, of all | people. had let an opportunity like ing to her. In the afternoon he tap- ped Mary on the shoulder and told} her to stand up. “I’m sorry I have to do it, but I’m getting too many complaints about your work. Your stitching falls apart before the dresses are even delivered. Don't worry, I won't take my losses out of your pay, but I'll have to let you go.” “You know that’s a lie,” said Mary. “You're firing me because you want to get rid of me so you can exploit the girls still more.” “Well, if you're so frank,” returned | the boss heatedly, “I'll be frank too. | I’m firing you because your mouth is too big. ‘You're putting crazy ideas into the heads of my girls, and it’s| for their benefit that I get rid of you. So never mind arguments. Go on, get out.” “Now I like that!” said Helen, standing up at the side of her friend. “So you're firing Mary because her mouth is too big, hey? You don't like her ideas, is that it? And you're doing it for our benefit, eh, big- hearted boy? Well, take 2 good load of this! I! she goes, I go too! Now meke up your mind quick!” The boss threw his hands to his head. “What's happening in my shop?- Are you crazy? Don't you realize this is my rush season and I can't afford to break in new girls? What kind of craziness; do you call this?” e * Tl say it’s rush season,” said Helen, resuming her old mocking tone. “But I don’t see you rushing to pay us for our extra work.” “Oh, I'll go crazy in another min- ute,” shouted the boss. “She wants to suck the last penny from my pock- et.) He turped upon Mary. “You see what yer crazy ideas did to a fine girl like Helen?” “Not my ideas, but overtime with- out pay,” said Mary. “Well, are you taking us back?” said Helen “....with an apology and time and a half for overtime?” The boss grew wild. “God in heav- | en, she wants to suck the last drop | of blood out of me. What does she| want from me?” “Oh, go suck a lollypop,” exclaimed Helen. “Come on, Mary, we'll find another job in a better dump than this one.” They walked out, leaving a dumbfounded boss behind them “You certainly surprised me,” said | Mary, after they had walked a ways up the street. “I never expected such splendid solidarity from you.” Helen said nothing. Suddenly she stopped stockstill and exclaimed, “well, Ill be damned!” “What's the matter?” asked Mary. “Can you beat it? .We forgot to take the rest of the girls out with Mary was startled. She had never that slip by! “Well, the next time we'll know better,” she said. “The next time,” said Helen, “we'll have the girls s0 organized that when the boss tries to put something over on us we'll all get up like one person and strike.” “Why, you surprise me!” said Mary, amazed at the transformation of her friend. “Listen,” said Helen. ‘Th-s little girl is surprising nobody moze than herself. What do you say? Let’s gol” soles were advertised and dried milk and unrationed meat substitutes. Professors and diatetic specialists had discovered that the turnip was an excellent and nourishing food for the populace. Coffee made of tur- nips! Turnip soup! Boiled turnips! “Every naval officer was allowed twenty bottles of wine a month. Three times a week banquets were held.” ‘Then came mass protest. The men refused their rations. The grand gold-spangled gentlemen in the of- ficers’ quarters called them “swine.” A Work On my way back from Edgewater, New Jersey, I met a Daily Worker newsie. “Buy the only workers’ paper,” he cried. “I've got no money,” I answered He gave me a free copy. I never read this paper before. I found that if every man out of work would read this paper, we would be able to put an end to all our misery in a very Short time. I thought I'd write in and let you know my story. July, 1930; I was laid off from the Ford plant, where I was working, on account of cut-down production. Since that time I have been looking for any kind of a job, one that any- body could do. But I got no job at all. In January, 1931, I made up my mind to stick to the Ford plant, and for two and a half months I went there every day, spending 40 cents a day for both fares, freezing 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. Only yesterday (March 31) at about 11 a. m. was I picked out for a@ job. A thousand men waited in line. Of course, each and every one wanted to be in the front. Police clubs brutally held them back. About an hour was taken to pick out 20 men. I was among them and we were again put into line Then we were put into line by twos and marched to the employment of- fice. At the employment office we got in one at a time, Signed the applica~- tion card twice and our name and address on another piece of paper. Then we were taken to the doctor, where all sorts of questions were asked again. We undressed. The doctor examined our heart, lungs, hands, eyes. I misspelled some |i ters. The docto rsaid: “Don't know how to read English?” ou Next country, date, name of ship, city, married, children, citizen, how long out of work, and s0 on. Finally, we were taken to the di- rector of the employment office and again examined. He looked at all of Thousands of joble: tions, and then be told, “You: By An EX-SERVICEMAN. from | ™ and were asked all sorts of questions. | I was asked when I arrived in this | ss wait outside the high fences of the Ford plants for their turn to be asked dozéns Of ques- The ‘Daily’ Saves ers’ my papers and then sa@idt “‘Your.reo ord does not allow me to take you back.” I asked him, “Why? There was no wer, The watchman showed |me the door. . | It was then 3 p.m. Tifeund my- self outside of the Fordy plant for- ever. It was'a very cold@day.’ I was hungry, freezing, no \moriey¥-No° job, my wife and three chtildteh: waiting for me for something. to eatii I must poy up my three months’ back rent. |I owe $150 to my neighborss pb) I got home at 5 p. micoi“Did you |get a j m my_Jwifec« “Pop, | to eat?”=from thy awhile=-came the 3g After landlord: “Well, did you-get a job?” | c en he heard the newsje sald: “T've been too good to you for three But, now you've gotto get of here.” My neighbors. asked for the return of :their.;money. wife and three children were cry< ‘There no way, out.for us to die of starvation. and exposure. That ht I-secretly..decided to commit suicide, so that somebody might take care of the,family, And 5 ting for the time when-I could | kill myself, I took .out..the~ Daily | Worker. In it there .was.an article about war. I read it very.carefully, I did not understand it rly. But what Ivrealized was : Iam an ex-servicenian and T | fought in the last World War. While I was fighting in France,and risk- ing my life, Mr. Ford was making millions of dollars, Today this sams “gentleman” told me that my record was no good, and so by,thig-he mans that I, my wife and children must die of starvation in the midst of plenty. i I accept your words,-“Hon't starve, fight.” I shall not commit suicide. But I'm going to feed myself.on the breadline and in whatever way I can. I'm going to be a Red and fight as a Red can fight; to the ut- most. bed Yours for the abolition of this sys- tem of robbers and starvation, On with the fight. —An Ex-Serviceman. | My | ing but igor r services are not needed. On the Picket Line Picket line, picket line, Picket every day Until Mr. Hickey will change his mind And give us back our pay. We'll sing you a song, We'll not make ft long: We'll sing of our children In the chapter devoted to the Bat- tle of Jutland is the most graphic picture of the hell of the battle that this writer has ever read. And it is not given without its political back- ground and the ambitions of the commanders of the German and British fleets, Jellicoe and Scheer. And here, too, is the individual tragedy of one of the impressed sail- ors, who, floating on a life-saving belt, from a sunken battleship, half- crazed, reaches over towards a float- ing sea mine, which he takes for a Hamburg waterfront prostitute, and touches off an explosion in the middle of the North Sea. Plivier brings in, in the most art- ful manner, the coming books of the commanding officers which, like Per- shing’s memoirs, are to serve as propaganda for the next war, These officers! How they gabble about strategy and pretend to be interested in the lives of the seamen! Plivier tears the mask off these pretenses. He shows that those rare and ex- traordinary officers who had even the remnants of human feeling to- ward the men they sent into hell, were ostracized and even deliberately sent into situations from which the military clique expected they would never emerge alive. Chee vai * fi The first mutterings of mutiny are here developed into the preludes for mass action. The seaman who, refusing to obey orders, yet not counting upon support of his com- rades, stoically nails his own hand to the table with his knife, is an ex ample; and Plivier matches this at once with the following: “In the’ German newspapers steel Murmurs arose in the fleet. “The workers ashore are begin- ning to understand. They can’t carry on either with empty bellies. It is beginning everywhere. That is why they make us do so much infantry drill If the workers ’ strike we are to fire on them.” ee ie This is the beginning of the end. On a mad adventure the German fleet commanders were attempting desperate things. To order the fleet, as the sailors knew, into andther A very bad book to send to your friends in the Navy. great battle that was’ nothing less than a massacre of their own men. The mutiny began: “Comrades! It is each for all and all for each! Better and end with horror than horror without an end. Down with the war!” This was the voice of 600. The w In the children’s club; They're young and they're bright, ‘They're surely all right; They're learning to fight very hard, “Yo Ho! Jing a ling a ling, Jing a ling a ling, Yo ho ho ho ; We are still kiddies, but some day we'll grow, Jing @ ling, jing a ling 2 ling, Yo he 40 ho ho : Young kiddies are we, don't you know, yo ho. officers tried to “find the leaders.” Court-martials. Death sentences. ‘We see these first sacrifices in the | death cells, before the firing squad. The Emperor makes a speech of sympathy to the working class! “Anyone who strikes is a scoundrel —we must stick it out. Carry on! Hold our tongues!” But the ruling class was unable to rule. in the old way; and the working class was unwilling to live— and to die—in the old way! The crews were deceived. The fleet was ordered to war. Maneuvers? No! They found from the tell-tale wind that the fleet was moving north- westerly! “Against England!” It was the hour of action. “Orders were given, but not from the bridge. ‘Out of your hammocks! To the for- ward battery! All hands to the for- ward battery!’” The officers pretented that the enemy fleet was in the offing. “Clear for action! All hands to baitle sta- Seen by the Compass By HATCTIN. FENNeBOL | Rouse me with the winds of harvest, | Waké me with the song of steel ships that plough the seas to new, harbors. © bold seamen, be bold forthe seas hold new mysteries of anchorage, The seas are older thay nten} « The seas are colder than the’ traves- ties of pain, : Slain sea-serpents, carcassed Moby dicks, writhe in memory again, Sailors, which way shall The east is red, The west is red, North and south are no'tonger point of the compass, but‘gteat towers of red that pelt the seas’ darkness. Gangway, for the new masters of the | ships, Tani | They have won new harbors, Gangway for the men who have known the seas’ coldness, 5° bs socnal tion!” The ixick failed. One after / anothet tne greyhounds of the Ger-_ “an High Sea Fleet fell out.of line The firemen had put. out the fires! ‘The officers, from the heights of in- solence, came to vain entreaties. Armories were smashed .in!, Crowe bars, hand-spikes, side-arms! Offi- cers trampled under -footl.. Others barricaded themselves under the armored deck. “ “Five thousand naval officers had sworn loyalty to the flag, ..The up- roarious banquets, raising. glasses filléd with champagne. They had repeated again and again that they would stake their lives:for, their flag and Emperor—only tires, defended the flag!” arts | gay rhe On the flag staff, where.for four and one-half years the symbol of im- perialism had flaunted, -was the red flag! This is a very, very ‘had. look to send to your friends inthe navy.