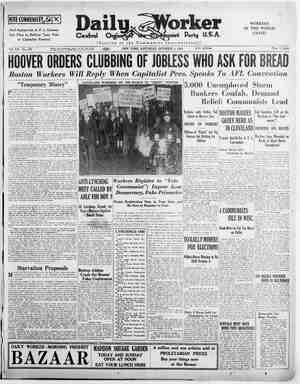

The Daily Worker Newspaper, October 4, 1930, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

_Page Foor _DA Communist, Fi armer Talk Things Over Farmer Finds That These Reds Are His Friends, | _ and That in the Soviet Union Peasants as Well as Workers Have Won Freedom and a New Life By HARRISON GEORGE Ja Chairman of Agricultureal Commit: | tee, Communist Party of U. 8. A: over | | | | Introduction: There are 6,000,000 farmers in the United States. Most of them are Poor Farmers, having little or no money or credit to serve them as capital, | unable to buy expensive as do the Rich Farmers and farm| corporations, and if they manage to buy, cannot use it profitably on their | small farms. About 40 percent are | tenants; millions are mortgaged. All of these Poor Farmers have been get- ting poorer and poorer and are des- perately loo; for some way out, | support their machinery | ng some way to live a families, It is to these Poor Far ers that the Communist Party speaks. munist: We, the Communists, ‘ou as a Poor mer to vote for candidates for Congr : Why? How Party munist rent political parties? | Communist: All the other parti are for the big ca s and against | all who toil. The republican and | democratic parties are openly for the | trusts, which are all controlled by| the big banks; while the so-called | “socialist” party is actually against | socialism, really the same as | other capitalist parties, but uses more “radical” talk to get the poor people, the workers and poor farm- ers, to follow them. But, where these fake “socia ruled in Germany and England, they are the best defenders of th api- talist class and the worst enemies of workers and poor farm Farmer: What about where the Communists rule, in the Soviet Union? The papers say that things are terrible over there; yet they ad- | mit that production is going up there | while it's going down here, and we| | | | | | | | | ferently | erty in land. and you can't pay. You can’t join a tive without turning in capi- rai bank And whe. you can't that, most of the poor can’t, you're left out, that’s a Farme as But how do they do it dif- a? Communist: revolution By workers and farmers seized the gov- ernment power from capitalists and landlords and abolished private prop- It belongs to the nation and the farmers paid no rent, it by a loan from the do farmers the | but | only taxes in what they raised. Many big estates, more all the time, are farmed by the government as Soviet farms, farms were united into 82,000 “Col- lective” farms; land, mals, everything. and Farmers’ private banks as credit, sets up machine repair Then recently 4,000,000 small | machinery, ani- And the Workers’ | Government—not the here—gives them | and tractor stations to help them plow and sow. This way, with less work, the same ing with others than by number of farmers farm more land, get better yields per acre (the gov- ernment gives them the best seed), | and each makes a better living work- himself. | They build big community houses (what you call hotels) with central kitchens, laundries, and so on, to make women's lives easier, and have theatres, libraries, schools. Here in America there are a few large scale farms, but nothing like that, is there? | Here | not! out and the Farmer: I should say we poor farmers are shut big farms belong to one rich farmer farms they run day and night and | goin’ back fo’ to work fo’ his people.” reduce costs that way. Farmer; Gosh, that’s wonderful. And you say they got that by making a revolution? i've seen a war be- tween capital and labor coming a Company shacks in which agricultural laborers are housed in the beet fields of hear of agriculture being “socialized,” j enormous farms with lots of machin- | ery, bigger crops at less cost than even here. ers putting their land, animals, ma- chines and so on together, even build- ing hotels, whére they live together like city folks and doing other things co-operatively. But we have co- operatives here, too, yet they don’t work that way. Communist: They can’t work that way here because we still have cap: talism here. The land is private property. Its owners demand rent. Money or credit (the us@ of money) is private property and/ its owners | demand interest. All machinery and animals used are private property, and the owners wouldn't think of let- ting the poor farmers who haven't got them use them without paying— We hear of all poor farm- | “ f Colorado long time. come here? Communist: Revolutions don’t just come.” They are made, and we revolutionary workers ask you poor farmers to join with us, to become members of the Communist Party, | which is the only working-class party, to support the strikes and struggles of the workers, to form your own revolutionary organizations of poor farmers and follow the guid- ance of the Communist Party which will help you right now in your struggles. Nobody's going to make a revolution and give it to you present. We all must get eeaiitee and fight as one. Next week we'll talk over this wheat business and what the capi- | talist papers are saying about the Soviet Union selling short. The Fish Comic Opera Reconvenes By PAUL VINCE The curtain rises on a scene Of desks and chairs of lustrous sheen Bet for investigation. - Mahogany and brilliant brass, Upholstered walls and polished glass Bring gasps of admiration. The delegates skid gracefully across the marble floor, ‘And spit with unctuous pride into a golden cuspidor, Each one selects a cushioned chair And poses carefully just where The cameras cannot miss him. They chant in accents clear and bold A lesson learned by rote:—“Uphold Our grand exploiting system!” The delegates arise and bow, with reverence turn pale, ‘Ae foolish Fish himself appears, pre- ceded by a scale. He grins and giggles foolishly, Remembering a lynching bee Which he had once attended. “Bring on the witnesses,” he cries. “See who can shout the loudest lies. ‘We have too long pretended!” Djamaraoff adagios across the marble A floor And somersaults into the golden cus- pidor. “The Reds! The Reds!” tones His voice, convulsed with dnguished moans, Emerges from the spittoon. “The Reds are growing fast as weeds. They're plotting dark and direful In muffled deeds, And we are not a bit too soon. ‘ll make us work to earn our bread; They'll make us work to earn a bed. Oh, miserable are we men! guide" ed us shovels, picks and How very devastating. Let's waste no further time this Fall, We'll pass a law and hang them all— No more procrastinating!” Bernadsky suddenly appears from somewhere in the rear, Smirks knowingly to each in turn, then screams in Fish’s ear: “Revive your flagging spirits, Fish. The ‘Whites’ anticipate your wish— These tricks we never fail in.” He prances to a fat, black bor; A button—presto! Shock of shocks! When out pops Grover Whalen! Then Groves flops his porpoise way across to Fish’s feet. He bows his oily head to wealth, and waves a printed sheet. “These forgeries,” sighs, “Were planned as a supreme surprise To send the Reds askidding. But something must have gone amiss— Td like to wriggle out of this. Command! I'll do your bidding.” he groans and AU minds are filled with doubts and fears, And each one stands with trembling ears, But voicing no solution. “We must go on,” cries fretful Fish, “And stop tiem now or get a dish Of rebet retribution!” Just then a rebel battle cry, “Work or wages!” rends the sky— As unemployed go marching by And chant of revolution— Assails the frightened ears of all Within the gilded meeting hall And leave them in confusion, From trembling fins Fish drops his scales As Gorgeous Grover Whalen wails “Hide quick or you're a goner.” And ites us strain our tender backs As laborers or seamen!” The delegates rise with o jerk, ‘And chorus: “Work They'll make And politicians frantically, Without a thought for dignity, Look for the darkest corner; As delegates and White Guards fight To get bellies out ht Ape beetle out of sigi But when is it going to| | By ELLEN WETHERELL The wom: an’s voice bell and on his stom- , that he might thborne!” as Rathore tu ch to his oth better. "s kickin’ up wo'ful up in the orf S The woman stopped ar the i lola > and tucked refractory “cornrow” back under her pink sunbonnet as he said, “I reckon they’s a-gettin’ ady fo’ the Day of Judgment.” “Who tole yo?” asked the man, push: bare, black toes deeper white sand. yo’ repeated Rath- 2 hot, tole borne, | “Who tole me?” said the woman loftils at’s my business, Rat! I told you the fact; the n’ up pow’ful up in the old Norf © an’ I reckon that Day of Judg- t ain't far tole rawir o! ye “Who demanded toes sand, only to nto the moist heat. sorne’s temp: from heard mo’ that an’ the Day of J ’ the papers an pulled an arm, | whipcords, from his head and rolled onto his e ers lie an’ lic The woman tossed the remnants of her ' to the watchful birds. the pickins’, time wi ; yo’ knows why we doan news in the papers; y ‘they doan’ mean the blac toe know the truth of thes r they am-workin’ fo! ay of ‘Judg! ‘ment, but I’se heard from Tilly's Sam. Sam's r at knows heaps |or a company. They have the trac-| to the ’cashon an’ tole all he know: tors and we have a spavined mule or} Tilly's Sam is goin’ back, but he two. | goin’ back to work fo’ his people Communi Corre and what's | The woman stood up, tall, raight, more even can’t use tractors to/ and handsome, her yellow face aglow the full capacity, while on Soviet|with enthusiasm. Sam am sombre black thborne turned hi: eyes up to his wife's clear, hopeful ones; he saw the light of expectancy in their “depths; he saw her lithe form, and he recognized her strength. WHAT FARMERS SAY The following is an extract from a country doctor who is evi- dently disseminating more than pills in his locality: Out here in the “Back- woods of Michigan” I felt as isolated as a fish in the middle of Sahara. But I soon found out the farmers were doing some thinking, too. When I told them about how radical the city workers were be- coming, and that I expected they might soon start a revo- lution like Russia had,— “When it comes, I’m ready for it,” said farmer No. 1. “It can’t come any too soon to suit me,” said farmer No. 2. “Yes, sir! The city men are going to do it, and us farmers have got to back ’em,” said farmer No. 3, emphatically. Genuine Leninist attitude, yet not one of them had ever read a single piece of radical litera- ture, nor knowingly spoken to any kind of a radical. Where did they get these ideas? “Oh, over the radio and in the newspapers,” they replied. “But these are unreliable capitalist sources.” “I know it,” said farmer No. 3, but us farmers are getting wised up lately and can see through a lot of it. I think we ought to invite those Com- munists to hold a meeting out here after harvest is over.” Then his glance dropped to his own rude limbs. He laid a strong, supple hand on the swelling bunch of whip- cords of his right arm, and drawled, “thar’s muscle ‘nuff, Nelly, an’ its muscle that Tilly's Sam is going to use fo’ his people.” “Certainly it am, Rathbone,” said she, “muscle an’ the grace the Lord gives both fo’ the work.” She tied the pink strings of her sunbonnet ftnto a hard knot, reflecting it was for six hours. “But how ‘bout brains, tily asked her husband. “Brains, Rathborne, am reckoned in ‘long with the grace. Brains am of no ‘count without the grace. Rathborne shook himself angrily, every whipcord in his dusky arm purpling the deeper. “There's brains in the old Norf State,” cried he. “Do's yo’ "low thar’s grace thar? There's brains way i‘orf in Boston.” Here Rathborne laughed a bitter caustic laugh. “Way Nort in Boston where brains am born, do's yo’ ‘low that am grace thar?” Nelly and Rathborne were now away down in the field, Nelly’s pink sunbonnet nodding close to her husband’s head, her lithe, yellow fingers darting in and out among the Nelly?” tes- the | push | The Farmer Discovers Who Are His Friends ILY WORREE _NEW ORs: _SATURDAY, OCTOBER 4, 1930 | bur: ing cotton boles. She called to | her husband over her shoulder: |What's goin’ to make the change, | Rathborne? Her drawling voice was very sweet. The Separation Line “T'se never reckoned that was goin’ to be ar : he, “’longs | the color of the skin an’ the kink jin the har am a separatin’ line be- twixt peoples.” Nelly shook her head lat Baihboree from over her aboulaer. | ‘I reckons,” said she, “that separatin’ | line can be rub out.” “Rub out!” cried he, ‘aas, rub out with blood, the white man’s blood, an’ the black man’s blood, to make the w ers’ free.” hat line am drawn mighty | down here in South Careliny |drawn sharp up in Boston,” TYPICAL harp 'n’ its said | Photo by Bw | Log and split mud hut, with stick “sr Rathborne, “whar black folks have {chance in the schools as teachers; no chance in the stores as clerks; no chance in the white churches with CHRISTIANS’; |the ‘WHITE no oh in the government. Ydas, , that separ line am drawn mighty sharp down south and ‘way “Rathborne (Nelly’s voice was very “am yo' goin’ to work | 2 ain Rathborne’s ‘I’se goin’ to work fo’ nobody.” Ff basket was swung high at his side, and was bulging | white with the cotton boles. “I'se | goin’ to work fo’ nobody,” he repeated |emphatically. His voice grated very |harshly on Nelly's ears. “Yo's needed,” said she. “Yo's has {a pow’ful voice, an’ with the grace I reckon yo’s kin beat Tilly's Sam. Rathborne swung his basket slow- ly. to his shoulder. “I’se goin’ to work for nobody,” replied he, dog- gedly. “I'se knows the way, but it am another thing to walk in that thar way.” “Yo! only needs the grace, Rath- borne, jes’ the grace. Tilly's Sam has the grace.” “Who tole yo’? Sam?” Of Rathborne’s irony Nelly took no heed. “Sam tole nothin’ but them | stories of them killin’s up in the old Norf State. All facts, said Tilly's | Sam, an’ Sam he reckoned with me that that Day of Judgment was com- | in’ fas’ to that old Norf State.” “What's Sam goin’ to do "bout it?” drawled Rathborne lazily. “Tilly's | Sam doan’ say what he am goin’ to |do, but I reckon he knows, an’ he |am goin’ to do it mighty quick, too.” “Did Sam tole yo’ the whole of that las’ Jim Crow affair in Washington?” asked Rathborne, after a pause -dur- ing which he had swung another | basket from his shoulder to the load. Nelly threw up her smooth, yellow arms. “All of it,” said she, “an’ mo’.” “What mo’?” asked he. Working for His People “Oh, all ‘bout the Negroes throwin’ of that Jim Crow car into the Poto- mac river,” Nelly’s voice was non- chalant, but in her eyes was a smoul- | der of indigation. “What am yo's_ sayin’, asked Rathbone. “Negroes takin’ rect action on that Jim Crow "s been lyin’ to yo’, Nelly.” Never,, repeated Nelly, hotly. “Tilly's Sam doan’ lie, Tilly doan’ lie, an’ they say that car Was saved | up Norf.” | soft and sweet) | fo’ yo’ peoples? | laugh was ca je. Nelly?” di- car? “God, Nelly, miracle ito save a Jin Crow car, now's tellin’ _me straight, jes what Tilly had to say.” Nelly realized that she had to tell the whole story—Rathborne was get- ting interested, and she reasoned that maybe he would go to work for his people. She went on: “At the Navy Yard that Jim Crow Car started fo’ Georgetown, an’ up the river. It was said that Northern tourists had found fault with the Negroes aridin’ with the white folk, so them tourists, Sam said, went to the commissioner in Washington city, an’ the commissioner put on a sep’- rate car, jes fo’ the Negroes to ride in an’ that car was called Jim Crow. Tilly's Sam’s cousin works at that Navy Yard an’ lives in Georgetown has a lil’ house there, jes fo’ him- self an’ his wife, Tilly's Sam’s cousin is jes as straight as Sam, an’ he got hot when he heard of this Jim Crow Car been put on the Georgetown line. Sam’s cousin is a union man, Rath- borne, yo’ know that.” Nelly gave a quizzical look at her husband. “Oh, I'se knows all 'bout unions,” said Rathborne. SHANTY OF SOUTHERN NEGRO Sam's cousin am workin’ fo’ his people.” “What yo’ mean, Nelly, how work- in’?” asked Rathborne. “For the freedom of his people; | to organize, so he says, to make union |men an’ women of his people-white workers, an’ black workers, Rath- borne, jes as workers—this is all, no white, no black, jes workers, doan’ yo’ understand, Rathborne?” “Go on, Nelly, witl? yo’ story. “Thar am, so Tilly’s Sam's cousin says, heaps of Negroes in that Navy Yard. They am sort of sep'rated from the white workers, but they am doin’ a pow'ful lot of thinkin’ ‘bout things in that city of Washington. So it was not hard to get the Negroes together with some white workers. An’ the commissioner appointed white FARMH: AND ing Galloway and dirt chimn men fo’ both conductor an’ fo’ motor- man.” “Oh, Oh,” cried Nelly, “am it goin’| j “Of course,” cried Rathborne. | to t our pickins’ from us? Po’ | “Curse the dev |Tily, po’ Tilly. What will Tilly do?| “So, continued Nelly, “on that very |She mos’ fifty years pickin’ in the | particular night, that car that made |fields, an’ now, she'll hat to die, many trips through the day, thbor crowded chock full of blac! all workers in that Navy all livin’ in Georgetown, Now, Sam says his cousin was a lea them workers, an’ he jes ‘till that car was Jes at the “ sin Bridge” that General Washington built ‘cross the Potomac River. Yo! knows ‘bout General Washington, Rathborne?. He was a big man, so Tilly's Sam says.” “General Washington owned slaves, black Negro slaves, Nel here Rathborne gave a husky laugh. “Go on,” he cried, “what mo’?” Nelly reached up for her basket that Rathborne had taken from her, and continued, “When that Jim Crow car had reached the river, an’ ‘way up to that {hain Bridge Gen- eral Washington had built, Tilly's Sam's cousin jumped to his feet, cryin’ Give me liberty or give me death. ‘Come on boys. All you good-work day folks, come on. This car stops heah, It am goin’ down the bank an’ into the Potomac River. This am the~nation’s capital city— we as workers, black an’ white, won't stan’ for this business in this city. All out, everybody out. An’ Rath- borne, such a rush of peoples to get out. Tilly's Sam's cousin's voice am a loud one, an’ he made every man an’ woman leave that car on the jump.” “Them was Patrick Henry's words,” said Rathborne, a bit net- tled over his lack of knowledge of the Jim Crow car affair. “Makes no differ’” said Nelly, “it am good sentimen’, give me liberty or give me death, That made the peoples rush out an’ give a helpin’ The Soviet Tractor Speaks Thing of iron and steel am I, Built to labor beneath the sky, Made to lighten the work of man, To grow his food by a better plan. Feed me gas and feed me oil, Drive me over the leagues of soll, Sell your horses for what they bring, Straighten your backs and learn to sing. List to the pants of my hot breath, As hard old methods I do to death. Those who made me did not see My future Rebet possibility. But over here in Russia free, Peasants save to purchase me, Beneath my paint, within my soul, They see the labor saving goal. han’ to roll that car down the bank to the Potomac River. They all cried with Tilly's San cousin, no Jim Crow car in this city, an’ they begins to rush that car off the tracks. Tilly's Sam says, that white motorman, an’ that white condugtor was as pale as death could make them, an’ they be- gin to swear at Tilly’s Sam's cousin, then to pray to him not to do the deed. They said, “We'll all lose our jobs if we ruin this car.” An’ somehow “An'” continued Nell; “Tilly's the words lose: our jobs went to the WE P Wont Give ME ane re valle HEAT FED heart of Tilly’s Sam's cousin—he was not at work for peoples to lose their jobs, but at work to organize them, So, he made that white motorman an’ that white conductor hol’ up their han's an’ pledge, sollem-like an oath that they would never again run a Jim Crow car. An’ them men swore they would join a union of colored an’ white men—organize all over in a new union. Sam said his cousin took the names of all the men on that car, an’ he said there were ‘bout 100,000 Negroes in Washington, an’ there were some one thousand Ne- groes standin’ by, ready to do all they could. ‘Tilly Sam’s cousin's heart soft- ened a bit ’bout all them men losin’ their jobs on the railroad, so he made a great speech for unions an’ liberty, an’ fo’ an army to stop lynching. We will not die, we will fight, cried Tilly's s cousin. I tell you, Rathborne, Sam said it was a big time, right on that historic ground, an’ we'll make | Sam jin South Carolina.” | | , an’ | Rathborne, ly’s | ee |take the cotton pickin’, | | | jit |that if he will stick with fore finger, with thumb*out, pointed to a little, crawling thing coming {down the last row. “Doe yo’ see it, Nelly, that car, | near the last row?” | “Over there, near the last row, | Rathborne, Rathborne, what am it? |Jes we a salamander, with lon it am pickin’ more historic by ‘this rallyin’ to- gether.” “T was proud, tell that it to Ri Rathborne, an’ I to hear id, TH he'll know his people, stick with the workers, pull with them, he'll be one of the brave men tell The Cotton Pickers’ Song “Nelly, Nel cried Rathborne, ‘ou am too good fo’ me. Come over », it is mo’ than six o'clock; \the | rds flyin’ low, an’ I hear the screech of an owl from the woods. You come with me, put yo’ han’s to | yo’ eyes, shade them, an’ jes where I point.” then look | Rathborne’s long n’ oh, hborne, it am wea What am it? “The new cotton picker, Nelly, an’ this field. It can pick Soviet The following article describes an agricultural commune in the Soviet Union, which is typical of one type of agricultural co-operative which more than siz million peasant house- holds have now joined. “Modern Farming—Soviet Style” is written by an American woman who has lived in Russia for the last ten years. The entire pamphlet may be purchased for ten cents from International Pamphlets, 799 Broadway, New York City. By ANNA LOUISE STRONG Soon I reached the collective farm, Hipiorsk. Tens of kilometers of rich, black earth in a single piece, bining twenty-two hamlets: com- the lands of such was «the commune “Fortress of Communism.” In its fields at regular intervals brigades were working—brigades of oxen, des of horses, and one brigade of seven tractors, from four to seven years old. They were driven night and day, stopping only for refueling, and “half an hour at night to cool a little, just so you can touch it with your hand.” At night the fields were dotted with lights of the encamped brigades. Music of balalaikas arose; motion pictures and political discussions were held in these encampments. All the co-operators said: “It is easier and merrier working together. Some plow, some harrow, some seed, and some mend harness. Now even the horseless peasant finds constant work, We are planting twice what these same people planted last year.” The commune, “Fortress of Com- munism,” was the type of collective that is growirig. Ten years ago, in the war-torn fields, seven families of red soldiers decided to plow to- gether, coming each from his own home in different villages. In the first years the men carried rifles to fields against the remnant guer- illas of White Gua and their Modern ‘Agriculture Style munism” was s0 successful that within a radius of five miles nine other communes and two artels (pro-' ducing co-operatives) had sprung; up,| In the field of Hopiorsk were ‘not only the peasants. Every kind of brigade poured into the villages— city workers, students, professor: judges, bookkeepers, young Commun- ists, to help the collective farms. A brigade of opera singers from Lenin- grad was touring the district to sing for the festive processions that opened the spring sowing. A white- haired professor of astronomy with a lantern-slide lecture was sent from the University of Leningrad to give cultural lectures to field brigades, Astronomy in the midst of class war, and problems of sowing, division of labor, repair of implements? “Why not?” said the president of the Com- mune. “The field brigades like cul- tural lectures.” Farm experts from every agricul~ tural college were mobilized to work out the program for collectives; brigades of Young Communists, y bred youths and maidens were fol- lowing a harrow for the first time in their lives, under the lafighing in- struction of the peasant boys and s Their “party work” was not merely to help the commune with labor, but to strengthen the local or- ganization of Young Communists. Newspaper brigades were also there to ferret out abuses and expose them. A ting them in their work was a brigade of judges, the most unique, I think, of all the brigades I met. These judges were thrown at once into villages where abuses were dis- covered, and six days later the news: paper, “Traveling Struggle,” was an- nouncing a dozen sentences of the officials exposed. (The,author then describes the other brigades which had visited this commune during the past six months. A brigade of women had been sent out by the Women’s Section of the Party to help draw more women peasants into the col- the kulaks (rich farmers). three times faster than we doe.” “Never you cry a ly,” said “we'll organize, we'll or- ganize, an’ you'll see us do it. We'll we'll take the we'll take the money, cotton fields, an’ yo’ po’ Tily won't want fo’ a good home. Nelly take my han’ an’ let us sing: Ho, the Car of Emancipation.” Ho, the Car of Emanct- pation Ho! the car of Emancipation Rolls majestic through the Nation, Bearing on its train the story, Liberty, a Nation's Glory. Roll it along! Roll it along! Roll it along through the nation— The workers’ car for Emancipation. See the mighty hosts advancing, Hear the music all entrancing— Lightning's flash—rolls the Thunder, Oppression’s Laws to rend asunder. Roll it along! Roll it along! Roll it along through the nation— The workers’ car for EMANCIPA- TION. From Dirie’s land, with its children toilers, Comes the cry to the nation’s work- ers, “We want to be free; we want to be free; We want to be free through the nation— Children all for EMANCIPATION.” * Roll it along! , Roll it along! Union Labor is on the tender; Men and women they'll defend her; From the Capitalist Gang they'll take the plunder, And send them all, By Gosh, to Thunder! Roll it along! Roll it along! Behold! Great Russia's new-born glory Shines resplendent through her atory— From vile oppression, death, starva- tion, She “went Over The Top” for EMANCIPATION. She's “Over The Top,” She's “Over The Top,” She's “Over The Top” for a workers’ nation— She's “Over The Top” for EMANCI- PATION. Roll it along! Roll it along! Roll it along through the nation— The workers’ car for EMANCIPA- TION. [Editor’s Note:—Will the author of | this story please communicate with Saturday Feature Page Editor, as her address has been misplaced.] NEXT WEEK On the anniversary of the death of John Reed, American revolutionary writer, the John Reed Club will con- tribute several articles and drawings for this page. By Rhyan Walker PEASANT SOLDIERS They collected enough harvest to build a central barn and dwelling, to which all moved. But during the | first four years they had neither beds nor bedding, but slept in hay. When their first really good har- vest, in 1924, gave them a surplus. they not only bought bedding, but made first payment on a tractor. To get it they sold livestock; they placed the cherished machine in their summer kitchen. On the night be- fore Christmas a gang of kulaks poured kerosene on the tractor and the building and burned it. The des- perate communers, by going on short rations, managed to raise 300 rubles for repairing it. Today the tractor still works in the tractor brigade. lective life, A repair brigade came sated IN THE RED ARMY, from the Moscow Amo Automobile Factory, consisting of five mechanics, who overhauled all the machinery as a free gift from the Amo workers, and another brigade from this same plant was sent to work with the com- mune for two years.) Such is the process whereby city workers are flowing into the villages, joining with peasants in the tasks of collective farming. It is breaking down the old barriers between city and village. No more shall there be workers and peasants; the words already are “commune workers” and “factory workers.” They are build- ing swiftly the basis of a socialist society in which the oldest an- tagonism, that between city and » By 1928 the “Fortress of Com- country, is disappearing. LABOR Last Sunday, after eating a hearty chicken dinner, a New York preacher stuck his fat head into sports news by announcing that “sports” is the best substitute for war.” He claims that boys and men should talk it over like sportsmen and substitute sports for the rough game of war. He goes on to say that sports will satisfy the “psychological demand” for rougher sports—war. This is a very clever scheme. to divert the attention of the youth and the worker sportsmen from the real causes of war, which are the greedy fights for world mar- kets and the capitalist system. Back to your Sunday dinners, you war makers; your scheme is to militarize sports and prepare the youth for an- other war! Another religious lie un- covered—chalk up another score for the workers! While preachers of the gospel are spreading religious dope and cooking up war schemes, the Labor Sports Union organized an open street race A GAME FOR WORKERS (From 5 to 30 Players) All of the players stand around in a group. One of them has a stick (about the size of a broomstick). Each player takes the name of any country in the world except the USSR. The stick represents the Soviet Union and Communism, The player with the stick throws it as far as he can, at the same time calling the name of one of the countries. The one who threw the stick and all the others except the one whose coun- try was called, scatter and run. The one who was called must pick up the Buena Vista, Ore. Dear Comrade: I have seen the puzzle in the Daily Worker and I thought that I would send you my answer to it. I hope that 1 did it correctly. This summer I worked picking fruits. The conditions are not so good for my dad has been out of work since April 22 and is trying to find a job, but there are none, AM the camps are closing down and it's hard See ee aes, SPORTS in Conneaut, Ohio, last Sunday, which kept many workers and youth from church. The workers stayed to witness the sports event and heard a talk on workers’ sports and the role of the church sports organizations. They learned also that the L. S. U, is preparing for its National Con~- vention in Cleveland, Ohio, which | will take place on November 7, 8 and 9, to make further plans for workers’ sports. _ The L. 8. U. has in its ranks only workers such as Comrade Liuska, @ stone quarry worker, who won over Mr. Fager many times this summer) before Fager was kicked out for pro- _ fessionalism and participation in bosses’ sports. Comrade Liuska won © the five-mile street run at Conneaut, Ohio, recently with a splendid time of 27 minutes and 24 seconds. More speed to you, Comrade Liuska! Down with the bosses’ Olympics of 1932. Hail the Workers’ Olympics of 1933) to be held in the Workers’ Republie of the Soviet Union! ” CHILDREN—THE USSR stick, and he becomes the Soviet Union, and must chase the other” countries, trying to win them for the revolution, Any player he catches he © touches with the stick (hitting not allowed) and that player joins him in — trying to catch the others, Any one |— caught by the second player must — hold him until the USSR can come and touch him with the stick. cel he touches him with the stick he} makes this country a Soviet and de-| feats the bosses. The game ends when all the countries |) have become Soviets. and nothing at all happens here. i Every day when the paper comes I), read it the very first thing. A bunch of the children and I gather round to) read the paper and discuss it. School is opening and some folks) even haven't the money to buy the books and clothes for their children, What are they going to do? e From your comrade, - Vora,