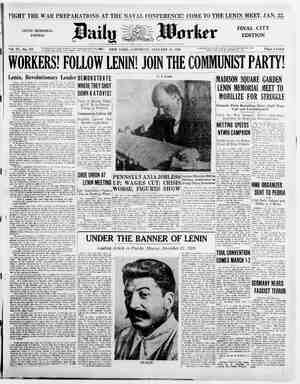

The Daily Worker Newspaper, January 18, 1930, Page 8

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

are, New York 28 and mail all a Page Eight * PARTY RECRUITING DRIVE City, N. ¥. checks to the ne Stuyves: Daily Worker ~] District w entering the een the ed the arge sed ri The re- sults correctness of the Pa ready to join the Party in Di Two, has now pz By the time Lenin M will have unde edly realized 75 of 1,000 new The develops y the very weak units of the Party working with de- he workers are numbers. 50 point neeting, we of our quota members. drive um 4d All others ition of the ve begun s to the objectives of the not only to secure the given bers, but, also and even more t a change in t ci n of the Pa uit at Least Bring the » the revolution- I into the is of 480 applica- e drive began will show s are following the line ruiting drive 480 new 1 ial com- arty in the r 100 of the Of these 20 are housewives and the z women. 293 nder 32 years of mbers are are Passes 50°% of ‘uota age 109 the the are workers e working in r st are lerks, re otfice wor stor etc. ‘0 work- are Latin e number a re native Americ hiefly from the nd t, 4; shoes, 16; 1, 20; needle,5; al workers are ¢ ustri t following building, labore printing, This analysis shows that we are not yet suf- ficiently orientated upon the basic industries and the Negro and native workers. The remain- ing period of the drive must be devoted not ‘ ting the remainder of our quota, towards re ing the work- ustries who are just as re- whom we are now recruit- reraft, 7 food, 6 but more espe ers of the basic sponsive as are tho: ing in larger pr. portions, but whom we fail to appr energetically and consistently. Compared to previous drives, we see a tre- mendous improvement which must convince every Con t of the splendid pc bilities to build ¢ rty in the factories and along the most exploited and oppressed sections of the working class. This should encourage us to greater efforts and better res: ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT NEW YORK DISTRICT (TWO) ; Letter trom Lenin to America In the middle of November, 1915, Lenin received a leaflet of the American League jor Socialist Propaganda, the contents of were proof of the internationalist course of the League. In answer to this, Lenin sent a lengthy letter to the League in which he enclosed the “International Leaf- lets” of the Zimmerwald Left, and the pamphlet “Socialism and War.” The text published by us is only part of Lenin’s letter, To the League for Socialist Propaganda in America the opportunists who should be expelled the Party, especially now, after their conduct during the war. If in every a small group (at present our Committee represents such a small p) could act and push the masses to the revolution, this would be very good. In all crises the masses are unable to immediately get into action, they need the support of small groups in the central organs of our Party. Right from the beginning of the war, since September, 1914, our Central Committee ham- mered into the masses, not to listen to the lie of the “war of defense,” that they must break with the compromisers and the so-called “Jin- go-Socilaists” (this is what we called the so- cialists who at present stand for the “war of defense”). We think that these centralist measures of our Central Committee were use- ful and necessary. We agree with you that we must fight against craft unions and for industrial unions, ie. for big centralized trade unions and for the most active participation of all Party mem- bers in the economic fight and in all trade union and cooperative organizations of the working class. But people like Mr. Legien in Germany and Mr. Gompers in America we ¢con- sider bourgeois, and their policy in our opinion not socialist but a nationalist policy of the middle class. Mess Gompers, Legien and their like do not represent the working class. They represent only the aristocracy and bureaucracy of the working class. Your demand that the workers should “come forward” in masses, has our full sympathy. The German Revolutionaries and International- ists-Socialists have the same demand. We are trying in our press to define more in detail what is to be understood by “political mass action”—as for instance the political strike (which is very frequent in Ri street demonstrations and the civil war which from Workers! Join the Party of Your Class! Communist Party U. A. 43 East 125th Street, New York City. I, the undersigned, want to join the Commu- nist Party. Send me more information. Name .. Address .. eee UltY.cesccvee Occupation . . Age. Mail this to the Central Office, Communist Party, 43 East 125th St., New York, N. Y. | alliance with these people is a crime. is being prepared by the present imperialist world war. We do not preach the alliance with the pre- sent socialist parties (which dominate the Sec- ond International). On the contrary, we insist on a breach with the compromisers. War is the best object on. In all countries the compromised politicians, their leaders, their most influential papers and magazines, have really formed an alliance against the proleta- rian masses. You say that there are also in America, socialists who are in favor of the “war of defense.” We are convinced that an This means an alliance with the national middle class and with the capita and the breach with the international revolutionary working class. But we are for the breach with the nationalist compromised politicians and for the alliance with the international revolutionary Mars and parties of the working class. We never objected in our press to the unit cation of the Socialist Party and Socialist Labor Party in America. -We have always referred to Marx’ and Engels’ letters (especially those addressel to Sorge who was an active participant in the American socialist move- ment) in which both of them condemn the se tarian character of the Socialist Labor Party. We entirely agree with your criticism of the old International. We participated in the Zim- | merwald Conference (in Switzerland, Sept. 5 to 8, 1915). We formed there a left wing and presented our own resolution and a draft mani- festo. We have just published these documents in Germany and I am sending them to you (together with the German translation of our little pamphlet “Socialism and War”) hoping that you have comrades in your League who are familiar with the German language. If you could help us by publishing these things in English (this is possible only in America, we would then send them to England), we would gladly accept your help. In our fight for true Internationalism against the “Jingo-Socialists” we always refer in our press to the leaders of the policy of compro- mise in America (in the S.P.) who are for restriction of the immigration of Chinese and Japanese workers (especially after the Stutt- | gart Congress of 1907, in opposition to the decisions made there). We think that nobody can be an internationalist and can at the same time defend such restrictions. We maintain: If, apart from everything else, American, and especially English alists, who belong to a dominating and oppressing nation, do not fight against each and every restriction of immigration and against the occupation of colonies (Hawaiian Islands), if they do not | fight for the full independence of the latter, then such Socialists are in reality “Jingos.” In finishing, I repeat best greetings and wishes for your League. We would be very glad to get further information from you and to jointly carry on with you our fight against | the compromise politicians and for true Inter- nationalism. Yours, N. LENIN. There are two social-democratic parties in Russia. Our Party (Central Committee) is against the compromise politicians. The sec- ond party (Organization Committee) is oppor- tunist. We are against an alliance with them. You can write to our offitial address (Rus- sian Library; for the CC. 7, rue Hugo de Senger, Geneva, Switzerland). But better write to my personal address: Wladimir Uuja- now, Seidenweg 4a ILI, Bern Switzerland. A Soviet Tractor in the Field One of the tractors produced in the Krassni Putilovetz factory being manned by a worker on a co-operative farm. holdings with their primtive methods of farming. Notice the wide stretch of field in contrast to the old, small peasant It is tractors of this type that will in crease the grain yield even to a greater extent than already achieved under the Five-Ycar- Plan, y ty Baily 345 Worker Central Organ of the Communist Party of the U. S. A. N—Destroyer of Capitalism, Builder of By Mail (in New York City only’ By Mail (outside of New York City s! SCRIPTION RATES: 0 a yea 4.5 6.00 a year; $4.50 six months; $3.50 six months; $2.50 three months $2.00 three months aa = | Socialism By Fred Ellis “Then a moment will come when the movement will rush forward with a speed such as we today cannot imagine in our rosiest dreams.”—YV. I. Lenin. Editor’s Note: The following selection is taken from Lenin's essay on Karl Marx, writ- ten originally’ for the Russian encyclopedia -Granat, in 1914, and soon to be published by International Publishers in the Imperialist War, constituting Vol. XVIII of Lenin’s Col- lected Works. * ee By V. I. LENIN. As early as 1844 or 1845, Marx came to re- alize that one of the chief defects of the earl- ier materialism was its failure to understand the conditions or recognize the importance of practical revolutionary activity. During all his life, Marx, alongside of theoretical work, gave unremitting attention to the tactical problems of the class struggle of the proletar- iat. All Marx’s writings bear witness to the fact, especially the four volumes of his cor- respondence with Engels, published in 1913. The material bearing upon this still remains to be collected, organized, studied and ex- plained. Here we shall have to be content with a very brief account of the matter, em- phasizing the point that Marx justly consid- ered materialism with this side to be incom- fundamental lines of proletarian tactics were laid down by Marx in striet conformity with tical outlook. Nothing but an objective ac- «tionships of all the classes of a given society, and consequently an account of the objective stage of development of this society, as well as an account of the mutual relationships be- tween it and other societies, can serve as the basis for the correct tactics of the class that forms the vanguard. All classes and all coun- tries are looked upon not statically, but dy- namically, i. e., not as motionless, but as in motion (the laws of their motion being de- termined by the economic conditions of ex- istence of each class). The motion, in its turn, is looked upon not only from the point of view of the past, but also from the point of view of the future; and morepver, not only in ac- cordance with the vulgar conception of the “evolutionists,” who look merely at slow changes—but dialectically, “In such great de- velopments, twenty years are but as one day and then may come days which are the con- centrated essence of twenty years,” wrote Marx to Engels. At each stage of develop- ment, from moment to moment, proletarian tactics must take account of these objectively necessary dialectics of human history, utiliz- ing, on the one hand, the .phases of political stagnation, when things are moving at a snail’s pace along the road of the so-called “peaceful” development, to increase the class cofiscious- ness, strength, and fighting capacity of the most advanced class; on the other hand, con- ducting this work in the direction of the “final aims” of the movement of this class, cultivating in it the faculty for the practical performance of great tasks in great days that are the “concentrated essence of twenty years,” Two of Marx’s arguments are. of especial im- portance in this connection: one of these is in the “Poverty of Philosophy,” and relates to the industrial struggle and to the indus- trial organization of the proletariat; the other is in the “Communist Manifesto,” and relates 4 the general principles of his materialist-dialec- | count of the sum total of all the mutual rela-. , Single place a crowd of peopl plete, one-sided and more dead than alive. The | Tactics of the Class Struggle to the workers’ political tasks. runs as follows: “The great nidustry masses together in a unknown to each other. Competition divides their inter- ests. But the maintenance of their wages, this common interest which they have against their employer, unites them in the same idea of resistance—combination....The combina- tions, at first isolated....(form into groups and, in face of constantly united capital, the maintenance of the association became more important and necessary for them than the maintenance of wages....In this struggle— a veritable civil war—are united and developed all the elements necessary for a future bat- tle. Once arrived at that point, association takes on a political character.” (The Poverty of Philosophy, p. 188.—Ed.) Here Marx sketches, some decades in ad- vance, the program and the tactics of the in- dustrial struggle and the trade union move- ment for the long period in which the workers are preparing for ‘a future battle.” We must place side by side with this, a number of Marx’s references in his correspondence with Engels, to the example of the British labor movement; here Marx shows how, industry being in a flourishing condition, attempts are made “to buy the workers” (Briefwechsel, Vol. 1, p. 136), to distract them from the struggle; how, generally speaking, prolonged prosperity “demoralizes the workers” (Vol. IL, p. 218); how the British proletariat is becoming “bour- geoisified”; how “the ultimate aim of this most bourgeois of all nations seems to be to estab- lish a bourgeois aristocracy and a bourgeois proletariat, side by side with a bourgeoisie” Vol. II, p. 290); how the “revolutianary en- ergy” of the British proletariat oozes away (Vol. III, p. 124); how it will be necessary to wait for a considerable time “before the Brit- ish workers can shake off their bourgeois in- fection (Vol. III, p. 127); how the British movement “Jacks the mettle of ‘old Chartists” (1866; Vol. III, p. 305); how the English work- ers are developing leaders of “a type that is half way between the radical bourgeois and the worker” (Vol. IV, p. 209, on Holyoake); how, due to British monopoly, and as long as that monopoly lasts, “little can be expected of the British workers” (Vol. IV., p. 433). The tactics of the industrial struggle (in connec- tion with the general course and the outcome) of the working clazo movement are in the let- ters considered from a remarkably broad, many-sided, dialectical, and genuinely revo- lutionary outlook. On the tactics of the political struggle, the “Communist Manifesto” advanced the fol- lowing fundamental Marxian thesis: “Commu- nists fight on behalf of the immediate aims and interests of the working class, but in their present movement they are also defending the future of that movement.” That was why in 1848 Marx supported the Polish party of the “agrarian revolution—“the party which in- itiated the Cracow insurrection in the year 1846.” In Germany during 1848 and 1849 he supported the Left Wing of the revolutionary democrats, nor subsequently did he retract what he had then said about tactics. He looked upon the German bourgeoisie as “inclined from the very first to betray the cause of the people” (nothing but an alliance with the peasantry would enable the bourgeoisie completely to ful- The former ) , Now: The excerpts printed below are taken from Lenin’s famous brochure, “What is to be done?” which is included in Volume IV of the Collected Works of V. I. Lenin, just published by the International Publish- ers, 88t Fourth Avenue, New York. This vol- ume, published in two parts, includes all the writings of Lenin between 1900 and 190B, and covers the formative period of the Rus- sian Bolshevik Party. * * * (Trade-Union Politics) We said that a Social-Democrat, if he really believes it is necessary to develop the political consciousness of the preletariat, must “go among all classes of people.” This gives rise to the question: How is this to be done? Have we enough forces to do this? Is there a base for such work among all the other clasess? Will this not mean a retreat, or lead to a retreat from the class point of view? We shall deal with these questions. We must “go among all classes of the people,” as the theoreticians, as propagandists, as agitators and as organizers. No one doubts that the theoretical work of Social-Democrats should be directed toward studying all the fea- tures of the social and political position of the various classes. But extremely little is done in this direction compared with the work that is done in studying the features of factory life. In the committees and circles, you will meet men who are immersed say, in the study of some special branch of the metal industry, but you will hardly ever find members of organiza- tions (obliged, as often happens, for some rea- son or other, to give up practical work) especi- ally engaged in the collection of material con- cerning some pressing question of social and po- litical life which could serve as a means for con- ducting Social-Democratic work among other strata of the population. In speaking of the lack of training of the majority of present-day leaders of the labor movement, we cannot refrain from mentioning the point about training in this connection also, for it is also bound up with the “economic” con- ception of “close organic contac: with the pro- LENIN ON THE ROLE OF A COMMUNIST PARTY vare able to arrange meetings of workers who letarian struggle.” The principal thing, of course, is propaganda and agitation among al) strata of the people. The Western-Europea Social-Democrats finds their work in this fiel facilitated by the calling of public meetings t which all are free to go, and by the parliament, in which they speak to the representatives of all classes. We have neither a parliament, nor the freedom to call meetings, nevertheless we desire to listen to a Social-Democrat. We must also find ways and means of calling meetings of representatives of all and every other class of the population that desire to listen to a Demo- crat; for he who forgets that “the Communists support every revolutionary movement,” that we are obliged for that reason to enaphasize general democratic tasks before the whole peo- ple, wtihout for a moment concealing our So- cialistie convictions, is not a Social-Democrat. He who forgets his obligation to be in advance of everybody in bringing up; sharpening and solving every general democratic question is not a Social-Democrat. “But everybody agrees with this.”—the ir patient reader will exclaim—and the new in, structions given by the last Congress of the League to the Editorial Board of “Rabacheye Dyelo,” says: “All events of social and poli- tical life that affects the proletariat either directly as a special class or as the vanguard of all the revolutionary forces in the struggle for freedom, should serve as subjects for political progaganda and agitation.’ (Two Congresses, p. 17, our blackface.) Yes, these are very true and very good words and we would be satisfied if “Rabacheye Dyelo” understood them, and if it refrained from say- ing in the next breath things that are the very opposite to them. .Surely, it is net sufficient to call ourselves the “vanguard,’ it is necessary to act like one we must act in such a way that all the other units of the army shall see us, and be obliged to admit that we are the vanguard, And we ask the reader: Are the representatives of the other “units” such fools as to take merely our word for it when we say that we are the “vanguard?” By LEON PLOTT. What Inner Party Democracy Means One of the outstanding characteristics of a Communist Party is its principle of inner Party democracy. The principle of inner Party democracy presupposes: the election of all leading communities from the bottom up, the right to criticise all Party mistakes, and the discussion of all questions facing the Party by the membership. Thru the phinciple of inner Party democracy we increase the conscious- ness and the activity of our membership not only by having our members express their opinions in considering Party questions, but also by their participation in the leader- ship and execution of our Party’s tasks. The Party cannot develop unless its members discuss Party problems and take a critical attitude to the mistakes and weaknesses of the Party. But what are the limits of inner Party criticism? How far can a comrade go in his freedom of criticism? This criticism must be limited to certain definite condi- tions, namely, under no circumstances to de- viate in our criticism from our Bolshevik base and not to destroy our organization founda- tions. Our criticism must be revolutionary, constructive and to the point. In the past in spite of our long discussions and debates, we did not have real criticism. In the past criticism was understood factionally and was utilized not to correct the mistakes com- mitted by the Party, but only for group struggle. We must be against such criticism. The Leninist conception of criticism is: Leninist Conception of Party Question “It is necessary that every Party or- ganization shall pay much attention, that the absolutely necessary -riticism of the weaknesses and mistakes of the Party, or analysis of the practical experiences of the Party and mistakes committed, etc., shall not be directed on the criticism of groups, which have built themselves on some sort of a platform, etc., but on the criticism of all Party members.” (Lenin at X Congress, C. P. S. U.). As Bolsheviks, we not only can, but w must, severely criticise everything that rep: sents a diviation from Marxism-Leninism. A‘ ehe same time, the Party must struggle wi all the means at its disposal against thi “freedom” of criticism which would represent with itself “freedom” to advocate social democratic, petty-bourgeois views and _ anti: Party ideas in the ranks of our Party, whic would inevitably destroy its Leninist founda. tion. We therefore cannot speak of criticis: abstractly. Inner Party democracy presup. poses only such criticism which is revolution ary constructive, having as its aim th strengthening of the authority of the Party, the strengthening of the Party thru th elimination and correction of our mistakes. (TO BE CONTINUED.) fil its aims), “and to compromise .with the crowned representatives of the old order of society.’ Here is Marx’s summary account of the class position of the German bourgeoisie in the epoch of the bourgeois-democratic revo- lution—an example of materialist analysis, con- templating society in motion, and not looking only at that part of the motion which faces backwards, Lacking faith in themselves, lacking faith in the people; grumbling at those above, and trembling in face of those below. . . dreading a world-wide storm; nowhere with energy, everywhere with plagiarism... ; without initiative . . . a miserable old man, doomed to guide in his own senile interests the first youth- ful imvulses of a young and vigorous people. (Neue Rheinsche Zeitung, 1848; see iLterarischer Nachlass, Vol. III. p. 212.) About twenty years afterwards, writing to Engels under the date of February 11, 1865 (Briefwechsel, Vol. 111, p. 224), Marx said that the cause of the failure of the Revolution of 1848 had been that the bourgeoisie had pre- ferred peace with slavery to the mere prospect of having to fight for freedom. When the revo- Intionarv enoch of 1848-1849 was over, Marx was strongly opposed to any playing at revo- lution (Sehapper and Willich, and the contest with them), insisted on the need for knowing how to work under the new conditions, when new revolutions were.in the making—quasi- “peacefully.” The spirit in which Marx wanted the work to be carried on is plainly shown by his estimate of the situation in Germany dur- ing the worst phase of the reaction. In 1856 he wrote (Briefwechsel, Vol. II, p. 108): “The whole thing in Germany depends on whether it is possible to back the proletarian revolution by some second edition of the peasants’ war.”* Until the bourgeois-democratic revolution in Germany was finished, Marx directed all the attention of the Socialist proletariat, as far as tactics were concerned, to developing the demo- cratic enerey of the peasantry. He held that Lasalle ‘objectively betrayed the whole work- ing-class movement to the Prussians (Brief- wechsel, Vol. III, p. 210), among other things, because he ‘was giving comfort to the land- lords and to Prussian nationalism.” On Febru- ary 5, 1865, writing to Marx about a planned appearance of the two with a joint declara- tion in the press, Engels said (Briefwechsel, Vol. IIT, p. 217): “In a predominantly agricul- tural country it is base to confine oneself to attacks on the bourgeoisie exclusively in the name of the industrial proletariat, while for- getting to say even a word about the patriar- q “have demoralised the proletariat and taken the chal, ‘whipping-rod exploitation’ of the rural- proletariat by the big feudal nobility.” Dur- ing the period from 1864 to 1870 in which the epoch of the bourgeois-democratic revolution in Gerany was being completed, in which the ex- ploiting classes of Prussia and Austria were fighting for this or that method of completing the revolution from above, Marx not only con- demned Lassalle for coquetting with Bismark, but also corrected Wilhelm Liebknecht who lapsed into ‘Austrophilism” and defended par- ticularism, Marx insisted upon revolutionary tactics that would fight against both Bismarck and “Austrophilism” with equal ruthlessness, tactics which would not only not conform to the wishes of the “conqueror” the Prussian| junker, but would renew the struggle with him! upon the very basis created by the Prussian Tuilitary successes (Briefweehsel, Vol. III, pp. | 184, 136, 147, 179, 204, 210, 215, 418, 487, 440, 441). In the famous Address issued by the® International Workingmen’s Association, dated September 9, 1870, Marx warned the French proletariat against an untimely rising; but when, in 1871, the insurrection actually took place, Marx hailed the revolutionary initiative: of the masses with the utmost enthusiasm, say- ing that they were “storming the heavens” (Letter of Marx to Kugelmann).* In this situa- tion, as in so many others, the defeat of a revo- “Briefe an Kugelman, Berlin, Viva, 1927, letter dated April 12, 1871.—Ed. lutionary onslaught seemed to Marx, from the point of view of dialectical materialism, from the point of view of the general course and, the outcome of the proletarian struggle, a lesse evil than would have been a retreat from a posi-. tion hitherto occupied, a surrender withou' striking a blow, as such a surrender would fight out of it. Fully recognizing the import- ance of using legal means of struggle during periods of political stagnations, and when bourgeois legality prevails, Marx, in 1877 and 1878, when the Anti-Socialist Law had been passed in Germany, strongly condemned the “revolutionary phase-making” of Most; but he attacked no less fiercely; perhaps even more s0,° the opportunism that, for a while, prevailed among the leaders of the German Social-Demo- cratic Party, which failed to manifest a spon- taneous readiness to resist, to be firm, a revo- lutionary spirit, a readiness to resort to un- constitutional struggle in reply to the Anti. Socialist Law (Briefwechsel, Vol, IV, pp. 307, 404, 418, 422, and 424; also letters to Sorge.) é 3.