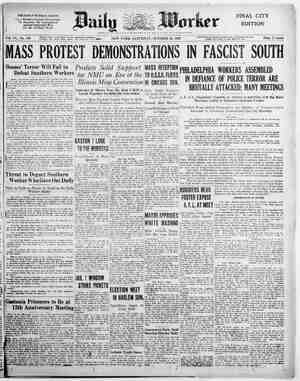

The Daily Worker Newspaper, October 26, 1929, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

f ; U 4 iy the ‘Square, New York ( Address and mail all Comprodaily Publishing Co., , N. ¥. Telephone Stu: cks to the Daily Worke! Inc., daily, ant | 1696- 26-28 Union Dt Sunday, at 26-28 Union a IWORK. 4 New York, N. ¥. exce} Central Orga f the Co: AQ? munist Party of the U. 8. A. a re SUBSCRIPTION RATES: By Mail (in New York only): $8.00 a year: By Mail (outside of New York): $6.00 a year; $2.50 three months $2.00 three months $4.50 six months: $3.50 six months; OF BREAD Reprinted, by permission, from “The City of Bread” by Alexander eroff, published and copyrighted by Doubleday—Doran, New York. TRANSLATED FROM RUSSTAN (Continued) Next they caught sight of 2 That kind could be seen in S lady with many combs in her hair. That father u peacocks. The lady stood on thi of a green car, there were two gold rings on her fingers and an ring glittered in one ear. Even her teeth were different from other peop} they were of gold. A crowd of children had gathered aro o at them, and the chil- mouth. The lady began throwi dren scuffled wildly for th up a shril piping like a tangle of up again and stood in a row, waitin) When the lady had thrown all the meat bones, she threw a crust of bread. A storm of bitter anger shook Mishk aney fe “She’s throwing bread around, the foo! He adjusted his s: and went over with hka to the fray. “You try to grab some, and I will too.” Mishka was not big, but he was sturdy. He took after his uncle Nikanor, who had bee a master at fist fighting. When that one boxed you over the ear—you heard music all through your head. and purposely flung strils dilated. He lunged The lady saw the boy in the wic a bigger piece in his direction. forward with his right arm, kno n two youngsters and sat astride a third. He forced the boy’s head into the ground, and began squeezing his throat as though with pincers. A little piece of bread, all squashed and covered with dirt, was his prize. Before he could get his breath, the lady flung another piece. With amazing strength, Mishka leapt for it. “Grab it, Serioshka!” But a bandy-legged boy with a big belly was quicker than all of them. He tripped up Serioshka, who fell down right on his nose. Serioshka jumped up, saw no one near him and struck out with both hands, but his blow went wild. The bandy-legged boy flung aside a girl in a long dress, and bristling like a pole-cat, turned on Mishka who was running toward him. Two other boys yelled: “Give it to him, Vanka!” Mishka shifted his sack on his shoulders and pushed back the visor of his cap, which had fallen over his eyes. “Come on!” “Huh, do you think I’m afraid of you?” “Come on, come on, try it!” Again the lady tossed them a piece of bread. And at the same time some one threw a little packet out of the car window. “Oh, the devil take yo Mishka would have liked to divide himself into two halves, but it could not be done. He flung himself toward the packet. “There must be sSmething in it!” With trembling fingers he undid the paper—nothing but cigarette butts. “Fui, devils!’ May boils devour your body!” The game lasted a long time. Once Mishka threw two others, once they threw hmi. He had grabbed more than any of them, and he had not fared so badly at their hands either. Maybe he would bump into another peacock like that. let her throw things around, if it amused her. Anything, so he could get to Tashkent. And bring back fifteen pounds of seed with him, and bread—big pieces. The grave, tranquil,orderly visions of the husbandman floated through his mind, filling his heart with quiet gladness. The though of sowing his own field next spring warmed and comforted him. His thin famished body ached with the sweet languor of the soil. Serioshka had not succeeded in getting anything at all. He had caught one tiny morsel, but bandy-legger Vanka with the big belly had, wrenched it out of his hands, and scratched up his face for him too, with his long dog’s claws. They sat down together, back of the station. Mishka counted the crusts he had gathered and said: “Fine! Three for me, two for you.” Serioshka gulped down the crusts but the taste in his mouth grew still worse. “Mishka, give me a little more, I’m still empty.” “That’s all for now. We'll fill up with water and go to sleep.” “Well, just give me that tiny crumb there.” “Where?” “There on your knee.” Mishka had not had enough either; he fingered the bread he had stolen from the peasant and pressed his lips together. “Always give and give! And when will you start giving?” “TI gave you the nut.” “I won 4t.” Serioshka was silent. Mishka drew the nut he had won out of his pocket and threw it at his feet. “Go on, eat that, if you don’t want to be friends.” Neither spoke for a long time. “How many pieces of bread do you owe me?” “Three.” “How do you reckon that?” “Count them up—then you'll see. That time we stopped to rest, I gave you one, one at the station where we got on the train—that’s two; and just now I gace you two pieces—that’s four. I’m not like you, I don’t reckon more than there are.” Serioshka began to cry. “My insides hurt so!” he sobbed. In the night it rained. The fields around the station began to swarm with mujiks and women, the coals hissed in the campfires, angry curses flew back and forth. Some one shouted through the darkness: “Bring along the overcoat!” “Where is it?” The whole herd trailed over to the station, crawled heneath the cars. Only one woman who had been left behind in the field scolded furiously: “Nikolai, Nikolai, where has the devil dragged you?” For a long while Mishka and Serioshka splashed along through puddles, floundered around in dtiches. When they got to the station at last, it was too late, there was no place to sit. They squeezed up against the wall in the corridor, squatting on their heels. Serioshka’s stomach began t ohurt: “Mishka, I must go out in the yard.” “In the yard again? Run out by the wall there quick!” ‘You come with me.” Mishka spat in exasperation. “What a queer fellow you are, Serioshka! You need to go, so I must go too. There are no wolves there. No one will bite your feet.” Ten times Serioshka ran out, straining, sobbing, and each time he said to Mishka in a weak, freightened voice: “Mishka, it’s coming again. . .” “Well, try not to...” “I do, but it comes itself .. .” “Try t oswallow your spit.” “My insides are all upside down.” Mishka was tired of bothering with him and said sleepily: “It will get better, only don’t think about it. It’s diarrhea from drinking bad water. Serioshka tried not to think about it. He shivered, pressed close to his comrade to get a little warmer, and closed his eyes. “I’m cold!” In the dim light of the platform lantern big raindrops were falling. They splashed into the puddles, drummed 6n the roof of the station. A man in a leather cap came running by, his heels thudding along the corridor, and trod on Serioshka’s foot. Serioshka broke into a wail. Mishwa rammed his cap down over his eyes, and. asked wearily: “What are you groaning for, Serioshka?” “I’m cold... my head is burning . That was all they needed! Mishwa rose and pushed his way through the crowd, crying: Gy des, give a sick boy a chance to warm himself a little.” No one answered. All right, (Ho be Comtipued) 3 to call them | | THE HOUSE CLEANED, THE MINERS MINERS UNION MOVESIN. _ By Fred Ellis, | anything but anti-parliamentary. i , NATIONAL MANERS UX ton NN a RIES PR a eee The Face of German Social-Fascism (Continued) aa iy. While the union of reformist organizations with the machinery of oppression, and the ideology of economic democracy which expresses this union was being worked out in recent years, there seeemed to be an important—and for international fascism a characteristic—-sphere ir which fundamental differences between fascist and reformist ideology were apparent: this was the conception of the State, which was in- voked to establish order in industry and to enforce agreement between the classes. On one side the glorification of bourgeois democracy, on the other an assertion of its bankruptcy and the deliberate preaching of dictatorship as a higher State form; closely allied to this, fascism proclaimed the “sacred egoism” of one’s country as the highest rule of conduct in international affairs, while social-democracy indulged in pacifist phrasemongering. The differences were never so great as they seemed to be. Polish fascism and the military dictatorship in Jugo-Slavia, began their activities under the slogan of protecting and | defending democracy, or of suspending it temporarily only in order to re-establish it more firmlyslater on. Jt was only during the course of the dictatorship that distatorship was declared, more or less openly, te be the highest form of state organization. Even in Italy, before the present state of affairs was reached, there were various stages in the exercise of constitutional rights and various corresponding ideas as to the “ideal” type of national state. The ideas at the first of these stages did not differ greatly from the demands of German democrats and social-democrats for a “strong leadership in democracy,” and were The rattle of the sword, as recent years have shown, is but an occasional tactical maneuver in fascist dictatorships as well as in democratic states; it is not the normal, which in both cases consists in the justification of armaments by an appeal to the necessities of “defending peace,” “protecting the fron- tiers,” etc. If, in those countries where it is to a large extent based upon or- ganizing the petty bourgeoisie against the proletariat, fascism has de- veloped an open anti-parliamentary and anti-pacifigt ideology only very gradually, so that it is not complete even today—and in any case this development has occurred almost entirely after the seizure of power— it would be quite stupid to expect German social-fascism to fulfil its task of winning democratie and pacifist masses for war and dictator- ship by publicly renouncing a democratic and pacifist ideology. Social- fascism’s work on behalf of the bourgeoisie consists in transforming this ideology in such a way that it can be used in the propaganda for a fascist dictatorship, and for this purpose such a renunciation would be the worst possible method, This is the real reason why the group concerned with the Socialist Monthly—which has for many years de- | clared that parliamentary democracy is bankrupt, and hag advocated a “structural democracy” based on economic corporations, after the style of fascist syndicates, joking maliciously about pacifist ideology and openly sympathising with Italian fascism—why this group, although leading trade unionists and prominent persons like Severing and Wisgel belong to it, and although it has fairly correctly foretold social-demo- cratic tactics on all internal matters, cannot guide the development of social-fascist theory, but can only influence it from outside. In an in- dustrial country such as Germany, the task of social-democracy con- sists in preparing and organizing the fascist dictatorship by spreading ideas—if possible “Marxist” ideas—calculated to mislead the greatest possible number of workers, and not in openly and honestly expressing its treachery to the old principles. The Magdeburg S.:D. Party Con- gress was particularly significant because it took a definite step in guiding this democratic pacifist ideology into fascist channels, After German social-democracy had declared the rule of the bourgeoisie to be “socialism in process of becoming,” it was only right and proper that the social-democrats should solemnly announce their duty of defending that rule against all internal and external foes, The real idea behind the replacement of bourgeoig democracy by fascist dictatorship was expressed by Wels (S.D. leader) in a famous speech, in which he said that the dictatorship is at first established in the interests of a later “re-establishment of democracy,” and that the parliamentary crisis ig recognized to be only of a temporary character. Actually, it is clear that the longer the fascist dictatorship lasts, the smaller becomes the possibility of a return to democracy, and that once in the stream of “managing the dictatorship” (hich has its own internal logic, wherein one measure gives rise to an other) the theory to justify this management will be found and baged on “Marxist” prin- ciples (if this word has not been entirely discarded, as its spirit was long ago), as that the social-fascist dictatorship is the highest form of democracy, from which it would be senseless to return to lower forms. It is significant of the real spirit of the entire social-democracy that the lefts accepted Wels’ famous statement not in a critical man- ner, but as an indication of the partys growing militancy. _ Should the social-fascist dictatorship be established in Germany, it will differ from the Italian brand in its efforts to use with greater care extraordinary force, which is a part of every fascist dictators) and which is employed both in the form of “emergency m si ns ins Py 5 ‘ (which, nominally only temporary, outlive their legal limits) and in the form of the employment of “private” and “irresponsible” force exercised by organizations formally unconnected with the state, Since German fascism finds its chief support in social-democracy (as was to be expected from the structure of the country) which must have un ideology to cling to, state emergency measures will be the dominat- ing form. Severing’s speech in the Reichstag on June 27th indicated this. After the rejection of the law for the protection of the republic, he declared that the government was prepared to use the emergency clause 48 of the Reich constitution (a year ago the social-democrats protested against the use of the same clause to bridge over certain legal gaps). The actions of the Coalition Government are very greatly accelerating the development of the required ideology. There is also a good deal of preparation for the use of extra-legal force in the ac- tivities of the Reichsbanner, which will certainly be extended as the difficulties of the German bourgeoisie come to a head. The dominant | feature (as is to be expected considering social-democracy’s special function) is the tendency to make social-fascist organizations and their terrorist acts a part of the mechanism of the state apparatus. At the last conference of the leaders of the Reichsbanner, where the May Day struggles were discussed, the question of establishing connections be- tween that organization and the Reichswehr and Schutzpolizei (semi- military official bodies) was the principal item considered. It was stated there that they were only a hair’s-breadth off from doing so; this may be an exaggeration in actual fact, but it was an exaggeration designed to facilitate the ideologic and organizational preparation of social-fascist terrorist groups for the coming class struggles. Wels—as any avowed fascist might have done—referred to the strength of the reformist organizations as a special justification of reformism’s claim to exercise the fascist dictatorship in Germany. Actually, reliance on mass organizations outside the state apparatus is part of the nature of any fascist dictatorship, and gives it (from the bourgeoisie’s standpoint) an advantage over the traditional forms of military dictatorship. Ideological and organizational unity and the exclusion or violent elimination of any anti-fascist tendency, are the essential conditions for the usefulness of an organization as a pillar of fascist dictatorship. The greatest practical advance of German social- fascism at the present time is probably the progress of the trade unions and other mags organizations controlled by the reformists, along this road, It is impossible to enter into all the details of the reformist offensive directed to splitting all these bodies, Since we are dealing mainly with the ideology of German fascism, we must be content with pointing out that the measures responsible for splits and exclusions have undergone change in the last year or two. Previously Com- munists were excluded because they “brought politics into the trade unions” by expressing their ideas, and violated the “neutrality” of the nominally unpolitical mass organizations; now “neutrality” has dis- appeared even from the official statements. The connections of these bodies with the “trade union party” are openly proclaimed and Com- munists are excluded, not because they introduce politics, but because they carry on a definite, anti-social democratic policy and fight against the “trade union party.” At Hamburg Tarnov pointed out that the program of economic democracy would necessarily bind the unions more closely than ever before to the party working for that program in the state. Objectively, these ties are nothing new, but their open admission indicates” great progress in the development of these organizations towards fascism, because it prepares the minds of the members for the part which, ac- cording to Wels, these bodies will play in the coming dictatorship. The Reichsbanner bore typically fascist features from its very foundation, but the May Days, for the first time for many years, witnessed the trade unions acting as promoters and exponents, and finally as de- fenders of the white terror used againgt the working class (they jus- tified the prohibition of the demonstration as necessary to “protect their meetings,” and declared that “the interests of the community must be protected from a minority of disturbers of the peace”). This fact both implicitly and explicitly affirms the social-fascist character of their actions. The political objection of social-fascist arming, and the chief pur- poge for which the bourgeoisie requires this social-fascist development, is the coming imperialist war. In this sphere Magdeburg showed great progress in the development of fascism, \ So much has been said and written about the social-democratic program of defense that little further is necessary. Nor, after what has been said above, need we explain the necessity (from the standpoint of the special functions of social-fascism) of coupling pacifist phrases with the imperialist reality and why this in no way prejudices the fascist character of the pro- gram, Its fascist character is, on the contrary, intensified by the “concessions” made immediately before the Congress, to the critics within the party. The original statement on the necessity for an army (and therefore of the coming war) stated that, in view the “fascist and imperialist powers” threatening the German republic with counter-revolutionary intervention and new wars (according to Her- Les Suit ~yaceghinmemiainecracpc i lle gan coved gece ed geass J + mer a ‘ \ No Compromise! | No Wavering! The opportunity is not always offered to the “gentlemen of the press” to attend “secret” political meetings, as such attendance custom- arily leads to publicity, which, however, is ust what was wanted by the almost-forgotten, near-Napoleon, Alexander Kerensky, when he, in Paris, called the journalists to a “secret” session of counter-revolution- ists to hear the absurd yarn of one George Bessadovsky, who was dismissed from a subordinate post at the French embassy in the French capital recently but who refused to return to Moscow to stand trial for stealing a considerable sum of money. Bessadovsky chooses to paint his case as political, that he is a martyr to the cause of the Russian peasants, whom he fears to return to Moscow to face. But there are serious sides to this affair of counter-revolutionary thieves and blackguards getting together “secretly” with the kind permission ; of Monsieur Briand. ] Bessadovsky asked to join Kerensky’s group of counter-revolution, and Kerensky spoke for the applicant, explaining, so the capitalist press tells the world,-“that such hesitants, if turned down, would finally fight on Moscow’s side when the conflict to overthrow the Communist regime occurred.” So that it what is planned by Messrs. Kerensky and Briand! And in the same city, with equal “secrecy,” Briand permits the separate, but politically akin, Russian monarchists to organize, the eligibility to which is based on a satisfactory reply to the question: “How many Red Army commanders have you killed with your revolver?” Paris, the organizing center and haven of refuge for counter-revo- lution against the Soviet Union, under Briand is, however, a scene of implacable struggle for legal existence by the Communist Party of France, sixty Communists, includnig the leading mmeebrs of the Cham- ber of Deputies, having been arrested the day before Kerensky’s “secret” meeting and, added to the hundred arrested on August 1, in the Anti- War Red Day demonstrations, all are to be tried for “threatening the interior and exterior security of the state’—for treason. Nor is the insect Bessadovsky the only sudden convert to counter- revolution as the fight sharpens in France between class and class, as waves of strikes rise ever higher, caused by proletarian resistance to rationalization, worsening conditions and the growing danger of war directed first of all aguinst the Soviet Union. Recently, in the world capitalist press, another pimple burst In the form of flamboyant “exposures” by an hitherto unknown soldier of counter-revolution, Paul Marion, a petty-bourgeois intellectual, who sought a career in Communism. Being an nitellectual he was taught to need an education, and at what better place to learn than at Moscow, where, however, after working ni a minor position a while, he was sent back to France with the testimonial to the French Communist Party that he was a cheap careerist and an enemy of the working class, With this recommendation, Marion found it more than difficult to establish himself with the C. P. of France, and feeling expulsion com- ing his way, “quit before he was fired,” making use of his visit to the Soviet Union to sell himself to the bourgeois press, delivering reams of nonsense about the “failure” of the Five-Year-Plan at the very mo- ment the same papers were getting repeated assuranc from thir Mos- ' cow correspondents that the Five-Year-Plan is a marvelous success! Let no one think this constellation of events is grotesque or im- possible, that the French bourgeois press is so liberal as to argue on all sides. The whole wrold bourgeoisie sees with growing fear and dread the astounding success of the Five-Year-Plan of Soviet industrialization. The imperialist bourgeoisie knows full well that the accomplishment of the Five-Year-Plan is a sword thrust at its own heart, and it is precisely for this reason that it gathers up all the Kerenskys, all the Bessadovskys, the Marions and the monarchist officers of the Czar, and is preparing M. Briand of the “Right” capitalist party group to turn over the business of making war on the Soviet Union to the “Left,” as shown by the growing ‘left” face of the new cabinet. Such is tre galaxy of counter-revolution in the “republic” of France. What lesson for American workers in this? Plenty! Let none | forget that Bessadovsky cries out to Kerensky, and Kerensky cries to Briand to rescue the Russian peasant from the “clutches of Stalin’— which is what the international Right Wing renegades, whose Amer- ' ican champion is Lovestone—blabbers about when speaking of the So- , viet Union. And what says the vindictive insect, Paul Marion? “In Russia there is neither the dictatorship of the proletariat nor the building up of socialism, but the dictatorship of a caste and the burial of social- ism.” Glib phrases, and where can we find them better repeated than in the sheet conducted by one James P. Cannon! Then in the mouth- , ings of Trotsky! i And what must we draw as a conclusion from this international aggregation, what can any member of the Communist Party extract from all this, other than that these various gentlemen for various rea- sons, which have nothing to do with proletarian nterests, all fit into the scheme for war on the Soviet Union, the world plan of counter- revolution! And let no leading body of our Party tolerate their fledglings in the party of Lenin, the party of revolution! , Those who do not fight against them, those who keep silent, are not Commu- nists, but cowardly conciliators with counter-revolution, for whom this period of struggle leaves no room in our ranks. as German imperialism) a defensive force was necessary “to protect the self-determination of its (the German republic’s) people,” while the text finally adopted runs: “To protect their neutrality and the poli- tical, economic and social achievements of the working class.” Externally, this seems to indicate a weakening of the avowedly nationalist ideology (the German people’s right to self-determination), actually it is a further development of typical social-fascist ideology, which developed, not by simply adopting nationalist phrases, but by basing and justifying dictatorship and war on the special interests of the working class. In the coming war the question will be not so much of making propaganda for the war, as of having at the government’s disposal organizations to defeat the revolutionary proletariat and to maintain the war industries. Levi, a “left winger,” in his pamphlet on the subject, expressly emphasized the particular capacity of the working class to further a war “in its own interests,” because of their control of military supplies and their strong organization. In thus planning the future role of the organization (in which work left and right share) German social-fascism is carrying out the main object of its development. If the organizations are to be maintained as an ef- fective force, their fascist work must be based upon “the interests of labor.” The idea of the nation is not surrendered, but sharply under- lined by laying emphasis on the special interests of the working class in the war conducted by and for the bourgeoisie. This assures the bourgeoisie of organizational support from among its one real enemy, the working class. Magdeburg brought the ideological development of German gocial- fascism to a certain provisional conclusion. In its counter-revolutionary activities social-democracy will cast off the last “shackles” of its past and also thousands of workers which it has misled in the past—and, by virtue of its pogition, will become the strongest counter-revolu- tionary force in the country, attracting to itself the labor aristocracy and numerous petty bourgeois elements. Every step on the road to. social-fascism means accelerating and extending the next steps, as it affects the social structure of the party, repulsing workers and at- tracting the petty bourgeoisie, Jf German social-fagcism is to be use- ful to the bourgeoisie it had necessarily to develop out of a “prole- tarian” ideology, but every step in*this development takes it further from the starting point. Democracy and pacifism, two years ago.im- t portant planks in reformist propaganda had, at Magdeburg, changed from slogans of action (or at least things to be defended) into petty beautiful “distant objects” to assure which, for the time being, war and dictatorship must be accepted as part price of the*bargain. { The new elements that have come into the party will start with the “provisional” justification of war and dictatorship and will, in practice, reach their ideological justification, will reach a hundred per, cent fascism (which the leaders have done long ago). Magdeburg clearly announced the participation of German social-democracy in the anti-Soviet war. While Breitscheid, referring to the May struggles, } talked of the “impermissible interference” of the Soviet Government in German home affairs, Wels declared German capitalism to be a higher form of socialism than that in Russia, and Crispien referred * clearly enough to the necessity, in the end, of intervention, The campaign for the imperialist war of intervention against the Soviet Union, together with the greater use of the state machine in the class struggles during the autumn and winter, will bring .with it he great steps in the development of social- arcing piaaiae Se - Viena i I ed at an eat a ~—otpokec