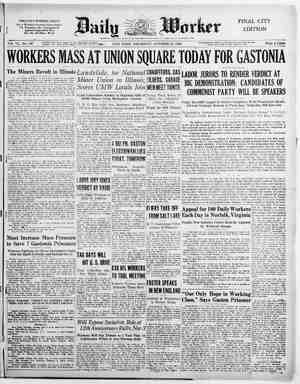

The Daily Worker Newspaper, October 24, 1929, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

a PablRREd by the Cor B 2 ‘ s to" the'Daily.’ Wo rodally Piblshing Cot Inc, aatly, except Sunday, at z Telephone Stuyvesant 1696-7-8. be * er, 26-28 Union Square, New York, N. ¥. +28 Union IWORK." Cable: ot ‘New. oe Be RH Gules " SOBSCRIP York ont Stee & year: ‘Oork): $4.50 six months: $3.50 six months; $2.50 three months $6.00 a year; $2.00 three months PARTY LIFE Bhiladelphia Plenum Challenges Detroit » “Socialist Rivalry” Applied to Party Building The Plenum of District 3, meeting ni Philadelphia October 20, amid great enthusiasm, sent the following telegram to District 7: District Plenum, Detroit, Mich.: The District Plenum of District 3 after hearing a report on the CEC Plenum and unanimously supporting the line ‘si down and de- ‘cisions made took upon itself the following concrete tasks as a means of putting this line into effect: to initiate a membership drive to last until May 1st by which time the ¢ t is to have three hundred new members at least one hundred of which should be Negroes and to es’ lish 26 nuclei in mills, shops and army. To establish a special distri page in the Daily Worker and to double its circulation in this distric This plenum has resolved to challenge you in the name of District 3 to do the same or better. With Communist greetings for a United Bolshevik Party. PLENUM DISTRICT THREE. PA The Face of German Social-Fascism By R. GERBER. The bloody May days in Berlin, the white terror loosed under social-democratic leadership and social-democratic slogans against the traditional mass demonstration of the proletariat, and the Madgeburg Congress of the S. D. Party which passed the social-chauvinist defense program—these events, occurring more or less together, indicate a certain maturity in the development of social-fascist tendencies in Ger. many. They justify us in speaking no longer of the growth of the leading reformist circles in the direction of fascism, but of definite, and conclusive signs of fascism in German reformism as a whole. It is, however, incorrect to see fascist development in Germany only in the growth of social fascism. There is also (as the Landtag elections in Coburg-Bavaria show) a great advance in the Nationalist-Socialist Party, whigh is openly and consciously fascist (an increase in votes of 100 to 150 per cent in one year) and which is recruited chiefly from the petty bourgeoisie and (in connection with the chronic difficulties of coalition government, expressing the general crisis of parliamentarian- ism) there is also a definite revival in the activities of the various de- fense organizatons, from the Wehrwolf to the Reichsbanner. German fascism is advancing in three partially separated columns, each active in a different sphere. It would therefore be wrong to ex- pect to find all the signs of fascism fully developed in one of them— the social-fascist column. It is true that in this article we are not dealing with German fascism in general, but only with social-fascism; still, we must point out its general connections which will give us a basis for the limits within which we may expect similarities to Italian fascism. It may be objected that in such a broad conception of fascism, fascism loses its specific content, that the totality of these “three columns” is nothing more nor less than the bourgeois reaction, and that it is not worth while seeking fascist elements in each of them. This alternative, put forward by the conciliato the denial fascism, or the obliteration of all differences within the bourgeois reac- tion, is false. There are a number of factors which are common to all forms of German fascism and which, taken together, differentiate fas- cism from other forms of bourgeois dictatorship. As distinct from a purely military dictatorship (which in recent times, it is true, tries to strengthen its position—and with a fair amount of suecess—by creating fascist support for itself) all forms of fascism are based upon broad mass organization whose activities are contrasted with the failure of bourgeois parliamentarianism and which—otherwise the masses could not be won for fascism—use a certain “anti-capitalist” phraseology, and refrain from appearing openly as representatives of capital. Fascism is differentiated from the terror exercised against the working class by a parliamentary democracy (a terror which in its out- ward manifestations may be just as brutal as fascist terror) in that it justifies its terrorist actions, not from the formal standpoint of the “will of the majority,” but by the particular weight of the interests it represents. o bourgeois democracy it opposes the “organic member- ship of society” by the cooperation of various group organizations— fascism does not deny class contradictions; it merely maintains that they can be overcome Within the framework of “common interests.” In this way it seeks to organize the anger of the masses at the bank- ruptcy of parliamentarianism in a manner which involves no danger to the rule of finance capital, and, when bourgeois democracy fails, tries to utilise that anger for the mantenance of bourgeois class rule in other forms. For the working class movement, the particular danger of fas- cism lies in its use of demagogy as well as terror, lies in the fact that it awakens among the workers the illusion that the dictatorship which it is anxious to establish, or has succeeded in establishing, is not the rule of their class enemy, but the result of their own work. In this sense, of course, fascism is the general tendency of the de- velopment of bourgeois democracy in the period of capitalist decline. The growth of internal and external contradictions necessarily leads to an intensification of the white terror against the proletariat and also makes the parliamentary democratic form of bourgeois class rule less and less useful for finance capital. On the other hand the increasing difficulties and working class revolt which is drawing more workers into the struggle, necessitate the creation of bases of support within the working class, support which is won by the corruption of the labor aristocracy. The smaller this aristocracy becomes, because of growing economic difficulties, the closer, by way of compensation, grows its con- nection with finance capital. For this limited group to fulfil its duty of binding the greatest possible number of workers to the policy of finance capital, it must convince them that the tendencies in the de- velopment of imperialism—increasing monopolization and trustification, state capitalism, the enrollment of members of the labor aristocracy in the executive organs of bourgeois class rule—are means of oveercoming “the bad side of capitalism.” This is but a paraphrase of the fascist ideal of the “organic state,” of “structural democracy.” The organiza- |THE of social | tional concentration of the national economy by means of state capi- | talism in the interests of finance capital appears as the “supersession of private capitalism,” and the use of degenerate working class ele- ments to suppress their class comrades as the “participation of the working class in the management of industry.” These basic elements of fascist ideology will, in the conditions of the third period, develop to a greater or lesser degree all over the imperialist world. It is there- fore of the greatest importance to deal with the growth of general fascist tendencies in those organizations where this course of develop- ment is in most glaring contradiction to their past history and where, consequently, the new state of affairs is most sharply expressed. I. The objective social basis of reformism generally is the corruption of the labor aristocracy (which*in certain circumstances may be very great and in some countries even form the majority of the working class) rendered possible by the imperialist extra-profits of the bour- geoisie. The question then arises: does the development of reformism to social-fascism correspond to a change in its social basis, to a change in the type of corruption. This is true of countries such as Germany. Before the war, and during the first period of prosperity after inflation, the skilled groups of workers were fairly well off, and reformism rested on the basis of this prosperous position of certain, generally highly qualified crafts, but in the period of capitalist rationalization this state o faffairs has undergone change. The special positon of these highly- qualified workers was lost as a result of the growing mechanization of labor. Statistics show a lessening in the gap between the wages of skilled and and the wages of unskilled workers, despite the growing wage differentation within the working class as a whole (cf. the state- ments on pages 167 et seq. in the report of the C.C. of the C.P.G. to the Twelfth Berlin ongress). The explanation of this apparent con- tradiction is not far to seek: capitalist rationalization draws large masses of badly paid workers (practically women and juveniles) into the process of production and depresses the wages of the working masses, while on the other hand it creates well-paid positions for a limited group, a group which by no means coincides with the skilled workng class, but includes also semi-skilled and unskilled workers. Individual workers who either act as foremen, or whose rate of work determines that of their fellow-workers, must, in rationalized under- takings workng on the transmission belt system, be urged to more intense activity in the interests of capital by means of higher wages, | HE STAIE “PROTEC? This gives the rise to a new and quite peculiar anti-proletarian attitude on the part of the new labor aristocracy. The compositor or mechanic who in former times had a good position by virtue of his professional knowledge, thought himself to be somewhat better than | other workers, he had more to lose than his chains and, in his principles, he supported capitalist society. In accordance with this attitude he was a reformist and Bernstein, who proclaimed the peaceful development of capitalism into Socialism, was his prophet. Beyond that, however, this labor aristocrat was united with all his professional colleagues as against the employer, fought with them for better conditons of labor and therefore had a certain understanding (even were it only expressed in benevolent neutrality) for the struggles of other groups of workers against their exploiters. Today, the man who has first place at the transmission belt and who receives higher wages in payment for driv- ing his fellow-workers to quicker work (from which they gain not even a temporary advantage) this man is an enemy to them. The old sort of labor aristocrat may have had no proletarian class-consciousness, but only a craft outlook, but the labor aristocrat of today is bound by no tie whatever to his colleagues; he is bound by many ties to the employer by whom he is bribed. His object is not common adyvance— even of his craft alone—but personal advance, if possible, out of the community of factory workers, among whom he is an outlaw, and into the category of “employes,” each one of whom, he thinks, “carries in his knapsack the marshal’s staff” of advancement into the bourgeoisie. | It is not only in.the factory that this movement of the new labor aristocracy out of its own class and into the middle class is taking place. The number of posts which they can fill is Imited; but the machine of bourgeois oppression is growing greater. Thousands of social-democrate workers are getting employment in State and local government bodies, the “fortresses of the working class,” in the police, ete. A few reach to the height of minister or police president, the highest levels of the pyramid, and are accepted in the society of the bouregoisie. They are only few, but why shouldn’t a parish councillor one day become a great minister? Those who have climbed to this eight influence the way o fthought of the whole. The desire for per- sonal social advancement assumes the form of an effort to obtain position in the State or party machine, and in the mass organizations which are closely associated with the State and in the consciousness of the reformist official there are many bridges leading to the State ma- chine. A wide labor bureaucracy ari oted below in the mass or- ganizations an dreaching above to al lbranches of the State apparatus; this bureaucracy serves as an excellent means of imposing the will of finance capital on the workers influenced by the reformists. However illusionary the experiments in indusrial democracy may be from the point of view of changing the order of society, they have the very real effect of employing thousands of workers (there are over 40,000 in the cooperatives alone, besides the “labor bank” and various industrial un- dertakings) in conditions which are better than those of the mass of the workers ,provided, of course, that they show themselves wliling tools of their party, that is, actually, of finance capital. The greater that social-democratic influence in local bodies grows the more do local undertakings, employing their thousands of workers, assume a social- democratic character. The character of German social-fascism is determined by this new type of corrupted labor aristocrat. Since the economic situation of German capitalism no longer allows for the corruption of whole craft groups to a greater or lesser degree, groups includng millions of Ger- man workers, only a limited number can be bribed with the decreased extra-profits; but they are corrupted more intensively. This state of affairs develops its own ideology, in which personal advance into the ranks of the petty bourgeoisie, and the hope of future advance into the bourgeoisie, is considered as the advance of the whole class, and these in their turn try to bind the workers to the bourgeoisie. Faced with their peculiar position in the rationalized process of production, faced with the fact that the general position of German capitalsm does not permit of concessions even to craft groups, they deliberately repudiate every idea of class struggle ,even in its craft forms, replacing it by the conscious glorification of common interests, both economic and political. This is just what fascism does, and the further this process develops, the more do the organizations involved assume a typically fascist char- acter. / es, Til. As we stated at the beginning, we cannot éxpect to find, all the elements of fascist ideology developed to an equal degree in German social-democracy is the fascist economic program. It is clearer and stronger than in the openly fascist organizations, whose economic ideas are exhausted in misty thoughts about the “expropriation of the banking and financial masters.” Social-democracy has this advantage over other fascist tendencies in Germany that, with regard to carrying on anti- capitalist demagogy, by which fascism hopes to win the workers, it was in its orign a really anti-capitalist organizaton. It was not necessaty to work out a new form of social-demagogy; it was enough to develop the old ideology (in doing which even the appearance of continuity was as far as possible mainained, the better to deceive the workers) in such a way that it could be used to deceive the masses. Two factors are essential to every fascist ideology as far as its industrial program is concerned (and this is true internationally): firstly, a struggle against one section of*the capitalists; this ,because it is deliberately aimed at only one section is always a sham fight; and secondly, the putting forward of demands which—apparently directed against the capitalists —are actually serving the interests of finance capital. In Germany, the first condition is fulfilled in most obvious fashion by the National Socialists who adopt anti-semitic slogans and differen- tiate between “creative” (i.e., industrial capital) and “parasitic” (i.e., bank and trading captal), the latter alone being responsible for the bad sides of capitalism. This primitve differentiaton is enough to win over the petty bourgeoiste—this being the specifc task of the declared fas- cists—who do, in fact, feel the weight of bank and trading capital. Social-democracy ,which has to face a do tute class trained for many years in the ideas of Socjalism, could do lle with si is the industrial capitalist whom the worker feels t obe his natural enemy; and the old appeal of social-democratie coaltion policy to bank and trading capitalists, who were regarded as “reasonable,” as op- posed to “scoundrelly” capitalists and'who (or whose democratic party) were for a time the chief object of social-democratic coaliton policy, has become pointless because of the monopolst development of German capitalism, because of the practically complete amalgamation of bank- ing and industrial capital. In its agitaton now, reformism simply draws a distributon between “reasonable” and “unreasonable” capitalists, ‘ac- cording to their readiness to enter into coaliton with the socal-dem- ocrats, to support a “democratic-pacifist” government policy, and to use more refined methods of abitration as the exploitation of labor power increases. The special ‘capacity of social-democracy for government, its appropriatness for carrying out a fascist economic policy in Ger- many, lies in avoiding discrimination aganst certain domnant sections of the bourgeoisie. Even the large landowners who were long described as wicked capitalists in socal-democratic agitation, and who are not quite in favor today because of ther reluctance to enter into a coalition, were recognized as vital components of the national economy, in the agrarian program of the 1927 Kiel S. D. Congress, and the “commu- nity” must preserve the vitality of that economy. Recently (June, 1929) the social-democratic members of parliament have been very actively trying, in cooperation with the national junker members, to establish a State monopoly in grain trading. According to social-dem- ocratic ideology toflay, the capitalist may be fought with the weapon of the “community” only when he does not submit to “common inter- ests,” i.e., to the will of finance capital. In his speeceh at the Hamburg T. U. Congress, an din his memorandum submitted to the Congress, Naphtali declared that the replacement o ffree competition by mono- polist organization was proof that “capitaalism can be bent before it. is ripe enough to be broken,” and that “the advance of monopolist capi- talism indicated the victory of socialist tendencies over this ‘bent’ capitalism.” This brings us right up against the positive side of the fascist economic program, the side which, as stated earlier, is most clearly expressed in the S.D.P.—that of economic democracy. The Hamburg T. U. Congress in September, 1928, expressed these ideas definitely (cf. article in “Unter dem Banner des Marxismus,” German edition, Vol. III. No. 2. “Industrial Peace and Economic Democracy.”). The fundamental idea was expressed by Nolting in a speech at the Frank- furt T. U. Delegate Conference on November 1, 1928: “The worker «must be placed where industry is really carried on, that is, on the management of monopolies. The introduction of workers into the control of monopoly management is the meaning of economic democracy. This change sometimes takes place with- out any activity on the part of the State, which assumes the right of control and supervision. The worker has a part in this control - because in a democracy the popular will is decisive. What is new about it is this—that representatives of workers’ organizations should be placed by the State in part control of monopoly organ- izations.” In both cases the road to the “worker’s voice in the control of industry” lies over the bourgeois state, and, quite logically, Tarnov said at the Hamburg Congress that making economic democracy their central slogan would bind the trade unions “still more closely to the democratic state.” The other aspect of this ideology is the denunciation of the “obsolete” method of class struggle against the employer, its place being taken by a “worker’s voice” on the supervisory council, guaranteed by the bourgeois state. This was expressed, in a primitive but objective fasion, by a delegate to the Hamburg Congress, who said: “The class struggle has moved from the street to the negotiating room.” The social-fascist. theory of econgmic democracy is the modern form, corresponding to the present situation of finance capital, of the old revisionist thesis of ‘development nto Socialism.” The reformists continually emphasize—to avoid the reproach of having surrendered their Socalist aims—that their economic democracy is not in contra- diction to Socialism, but is “Socialism in the process of becoming.” This argument, seized upon eagerly by the left, only makes the be- trayal of Socialism more obvious. For economic democracy, as preached by the reformists, is nothing but the developing process of the mono- polization of industry, plus the growing importance of State capitalism in monopoly capitalism, plus the emolument of the labor aristocracy into the bourgeois machine of exploitation and oppression. These are not figments of the imagination, but the real tendencies.n the develop- ment of German, as of every other, imperialsm. The reformists mean something very real by economic democracy, The treachery lies in this, that the strengthening of the bourgeois apparatus of oppression and the increasing enrolment of workers, estranged from their class, to fight their own class comrades, is put forward as an achievement. To “retain the aims of Socialism” seems therefore to mean the pro- | clamation of capitalism today as “Socialism in process of becoming,” | | and the tendencies in its development as Socialism already achieved. These ideas were expressed in the rsolution passed by the Hamburg Congress, which states: “The democratization of economy leads to Socialism... The change in the economic systém is not an aim of the distant future, but a process which is developing from day to day. The demonstra- tion of economy means the gradual elimination of the rule based on the possession of capital and the transformation of the leading economic bodies from bodies serving the interests of capital to those serving the community. The demonstration of economy takes place gradually wit hthe structural changes in capitalism which are be- coming increasingly obvious. There is‘ no doubt that development is leading from capitalist private industry to organized monopoly eapitalism.” This program is differentiated from any fascist declaration only by its terminology, only by the fact that, in deference to a working class brought up in Socialist traditions, a Socialist Jabel is stuck on to were BY i ALEXANDER NEWEROFF THE CIT OF BREAD Reprinted, by permission, from “The City of Bread” by Alexander Neweroff, published and copyrighted by Doubleday—Doran, New York, TRANSLATED FROM THE RUSSIAN A Ree (Continued) Mishka lay on his back in the grass, and gazed long at a curl; blue-gray cloud that floated across the distant alien sky. In his euiteatl. it was as though needles were stabbing him, his mouth filled with spittle that gummed his lips together. He spat, and pressed both hands hard against his temples. Then he began to put on his sandals; absent-mindedly he drew them on, inspected the strips that bound them, and the torn heels ,and languidly shook the dust out of his stockings. He stole glances at Serioshka’s trousers pocket where the precious iron nut lay. He scratched his head. Luck comes to those who do not deserve it. See how it was. He, Mishka, took care of everything, ran around and found places on the train ,helped the other climb up on the car, and then it had to be Serioshka who found the nut. Mishka beat his stockings against a brick, and said: “All right! Keep your nut! I don’t need it... .” Serioshka made a wry mouth, his eyes began to blink. He had been clutching the nut so tight that it was all damp with sweat, as though it had grown to his palm. There would be a fight if Mishka tried to get it away by force. What did he have to be so high and mighty for?—wouldn’t let you do anything! Mishka watched him moodily. mt 4 “You're a fine comrade! It’s worth while traveling with you! When it comes to gobbling up my bread, you’re ready; but when it comes to the nut, you’d rather choke than give it to me. Who saved you from the Tcheka? Next time you get caught, you won’t find me worrying about you. And I won’t give you any more bread either, and I’m going alon, without you. You can stay here with your old nut...” Serioshka’s lips quivered, his eyes grew dark with resentment. For a moment he let his fist open weakly, but then he shut it again tighter than ever. It was not the nut he cared about, but he was angry at Mishka. Was Mishka his master, that he should always keep him from doing things? They got up and went further. ‘ a Serioshka wanted to walk beside Mishka, but Mishka pushed him away. “Go on, I don’t want you.” ; ee Serioshka snuffled, and trotted along after him. He looked hard at his iron nut, rubbed it on the knee of his pants. What a pity! He would have to give it up. Mishka had brought him here, way off into this strange land, and now he might go and leave him there, on the road, with the Kirghiz and everything. : 2 OF ee, He Icked the nut a couple of times with his tongue, then said sud- denly: “Mishka, let’s draw lots for it!” “T don’t want it.” “Do you think I care about it so much?” Mishka breathed more easily. =“Do you see, little devil? You won’t get anywhere without me.” He was very sad. and a short one. But Serioshka changed his mind. “You'll fool me. Let’s do it a different way.” “All right.” Mishka picked up a stone and said: ‘ “J'll shut both my hands. If you pick the hand with the stone, the nut is yours. If you pick the hand without the stone, the nut is mine.” For a long time Serioshka pondered which one to choose. He screwed up his eyes, turned away, even prayed silntly: “Dar God, let me win!” “Hurry and choose!” “Left!” Mishka clicked with his tongue triumphantly. “Huh, you little fool! I always hold things in my right hand... .” Serioshka handed over the nut, and began to feel hungrier than ever. Wit hthe nut in his pocket he had felt fuller inside, but now there was only emptiness in his belly, and in his mouth was the evil taste again. Mishka boasted: “What a lucky fellow I am! When I ge home again, I'll make something out of this nut, or maybe I’ll sell it to the blacksmith for a hundred rubles.” Serioshka raised his head. “A hundred rubles! That’s too much!” “Why? It’s iron, and it’s good for almost anything.” “You won’t get a hundred.” “Do you want to bet?” VOR Serioshka was very downhearted. He went on for about twenty paces, then he consoled himself. ee ahead and sell it. I’ll find another one, a better one too, cast iron!” Being de (To be Continued} on of individual interests by means of greater organization (individual interests being called “capitalist interests” by both reformists and fascists, because for them capitalism as a whole is not capitalism at all) in favor of the “interests of the community,” the State playing a leading part in the change. We cannot ask more of the social-dem- ocrats, and it would be childish to base the recognition of the presence of social-fascism on the surrender of the word Socialism. For the bourgeoisie, the specific value of social-fascism consists in the fact | that the fascist program is preached with a Socialist phraseology, just | eas the specific value of the Hakenkreuzlers (a fascist, anti-semitic organization—Ed.) for the bourgeoisie (including its Jewish members) lies in their fascist program preached with an anti-semitic phraseology. With the formula of economic democracy, German reformism, becoming | social-fascism in the process, found the idea best adapted to its nature whereby to.win over the largest possible number of workers to support its own desertion into the other class camp and the advancement of certain corrupted working class elements into the petty bourgeoisie, binding them, in this way, to the bourgeoisie. The consequence of this was drawn by Dittman at the Madgeburg Congress in his speech on the defense question (a question also affected by these ideas, for they form the basis of social-chauvinism) when he said: “We are no longer living under capitalism; we are living in the i] transition period to Socialsm, economically, politically, socially.” / t “And: “In Germany we have ten times as many Socialist achievements to defend as they have in Russia.” Whence follows, naturally, the results of this defense, particularly against the Russians, so backward in Socialism. Wheher this form of society, to be defended against the proletarian dictatorship and real Socialism, is called Socialism or corporate economy (as Italian First they decided to put two sticks into Mishka’s cap, a long one