The Daily Worker Newspaper, September 17, 1929, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

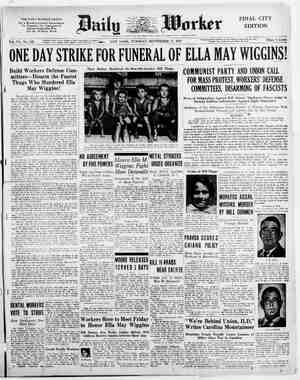

* tionary labor movement). Cor iets Pudlished by the Comprodaily Publishing Cox Inc. pie ¥en square, New York City, No Y¥. Telephone Stu oun “address and mail all checks to the Daily. Workei The Labor Movement in the Philippines E labor movement fi arose in the Philippines about thirty nfluence of the National Revolution of under the di q led to the fo ion of the First Republic in the : jis revolution the role went over spontaneously to tthe proletarian elements in the towns and to the poor strata of the population in the rural d a movement that was headed by Andres Bonifacio against iously alarmed at losing thei tened to capitulate to th mn Subsequently, the Amer tion in the Philippines v tion) and commenced to downing be riches ans and tht ed the S irected prima appress the emar rgeois clique who, s and other privileges, betrayed the rebellion. aniards (for the revolu- against Spanish domina- ipatory movement of the people. It was only after three years of bitter struggle that the U.S. A. finally got ds. The small labor nat se Manila, the capital of the islands, round about 1901-2 were inspired chiefly by a group of prom nent intellectuals who } ved their edu mn and knowledge of sh labor move- , formed chiefly the labor movement in Sp And so we find ment of that time, with its small craft organ’ it of ndicraft i the movem ter and man, was thus the Philippines. dustry great] and to this day have a Despite the peacef generally, severa! strikes occurred d the movement s of the e- ment thanks to the results of the high cost of living t nd the econ- omic policy of the Americans (with the A ns in control the trade turnover rose from 62,000,000 peso in 1903—a growth that was only possible by of the country). The repressions directed by the American authorities against the strikers and their leaders strengthened the peaceful tendencies in the labor movement, the more so, since at that time the labor organiza- tions were not purely proletarian in character, there being many small shopkeepers, handicraftsmen and others among the memt The bitter struggle between the labor leaders (the majority of whom-were not workers at all) to use the labor organizations as a means of getting parliamentary seats, started during the first elec- tion campaign (1907) when the parliament of the Philippines was first established after the Americans had “pacified” the country, extremely weakened the labor organizations. It was universally recognized at that time that the labor movement would have to gather its forces to- gether and reorganize itself—a task that was undertaken by the Printers’ Union—the most progressive labor n at that time. Sev- eral new unions catering for the tobacco worl seamen, carpenters, tailors, boot and shoe operatives and others were organized on a new basis which made it impossible for any of the masters or employing class to become members. By the first of May, 1913, all these organ- izations had met and formed the Philippine Labor Congress—the largest National Labor Federation in the Isla 5 to 132,000,000 peso The bitter struggle that arose again between the politicians—the | congress leaders—seriously retarded the work of the congress and in 1916 a group of unions headed by one Balmori broke aw group formed the so-called Federation of Labor which sub: became the extreme Right wing of the labor movement, zealously s porting class collaboration. This Federation is still. the loyal agent of the capitalists in the labor movement of the Philippines. At the present time the percentage of workers organized in the Philippines is very high indeed. In 1927, of about 300,000 workers em- ployed in industry, transport and trade (including lumberers and fishermen working for hire), there were 92,000 organized, of whom 66,137 belong to the Labor Congress (not counting the agricultural workers); 3,268 belong to the Federation of Labor, while 22,786 were lined up in the Independent Unions. The Peasant and Agricultural Workers’ Confederation, affiliated to the Labor Congress, likewise became a very strong factor in the labor movement. However, the percentage organized among the agricultural workers is altogether negligible. The Confederation has less than 15,000 workers lined up, although there are more than 2,000,000 workers employed in the agri- cultural trades of the Philippines. The growth of the numerical strength of the workers’ organiza- tions especially apparent during the post-war period beginning with 1917, went hand in hand with the rapid growth of industry. At that time many new large-scale enterprises arose, equipped on the latest engineering lines, employing large numbers of workers. There was also a marked ‘increase in the number of transport workers, as the railways were extended and other transport facilities introduced, Despite the fact that a large number of the workers were organ- ized in the trade unions, the mutual aid societies and other organiza- tions, the whole labor movement of the Philippines down to recent years was still characterized by its marked division, as seen in the early period of its development and a craft outlook. (For example, in Manila, alone there were eleven unions catering for the tobacco work- ers. Some of the organizations could not boast of any members out- side a given factory. There were five unions for the seamen, and so on.) The idea of class peace still had a strong hold on the workers, there were no militant leaders; neither were there many active trade unionists. It was the organizational structure of the Labor Congress, which is a loose federation of varioys organizations and the fact that no paper was published and no dues fixed, etc., that prevented the Congress from becoming a real organ uniting and leading the labor movement. And, finally, it must be said, the weakened side of the labor movement in the Philippines was its complete isolation from the international labor movement. Besides this, the absence of an independent labor party seriously weakened the unit weight of the labor organizations in the political life of the country. Prior to the formation of the Labor Party of the Philippines in 1928, the workers were mainly influenced by the political views of their leaders who usually belonged to one of the two bour- gevis parties. For example, in the struggle for national independence —sugi a vital question for the working masses of the Philippines—the workers followed the lead of the national bourgeoisie. But the last year or two marks a new era in the labor movement of the Philippines. It was ushered in by the tempestuous growth of the revolutionary movement in China and the fact that the Philippines were drawn into the orbit of the international revolutionary labor move- ment when the Labor Congress affiliated to the Pan-Pacific Trade Union Secretariat (affiliation was made in the middle of 1927 immediately after the Pan-Pacific Trade Union Conference had been held). Thanks to the fine work carried out by the most progressive and revolutionary section of the labor movement in the Philippines to strengthen the unions, to reconstruct them on the industrial principle, to get trade union activities going at the factories and plants, to strengthen unity and propagate the idea of international working class solidarity, urging an implacable class lead, and the strengthened strike movement of the last period, the successes already achieved in the trade union field have certainly been remarkable. For example, Philippine workers and Chi- nese workers came out together; Chinese and Philippine boot and shoe operatives struck for more than four months; the recent woodworkers’ strike should also be noted. The Chinese workers in the islands are united in the so-called Philippine-Chinese Laborers’ Association which set up close contact with the Labor Congress, despite the efforts of the native bourgeoisie to foster a spirit of national antagonism. Sev- eral strikes that arose at the end of 1928 and the beginning of 1929 were remarkable for the solidarity shown by the workers and the large numbers involved. The growth of the militancy and solidarity of the workers was seen especially during the strike of last December, when 10,000 workers came out to protest against the arrest of one of the tobacco workers’ leaders (who had struck a scab). The conservative elements, however, have been furiously resisting the continued radicalization of the labor movement. (In the Philippines the right wing of the labor movement is nicknamed the conservatives; the left wing—the radicals). At the outset this resistance was seen in the internal struggle in the Council of the Labor Congress and in the way the organizations controlled by the right wing leaders sabot- aged the new policy. » Subsequently, the intensification of the struggle between the two tendencies led to a split in the Labor Congress at the annual congress held at the beginning of last May in Manila and a new labor congress of the Philippines, known as the Proletarian Labor Congress was formed. Where the so-called conservatives are leading the labor move- ment is seen from the declarations made by their leaders (Tehadi and - others) after the split had taken place, which state, among other things, that the labor movement of the Philippines must now strengthen con- tact with the labor bureau (a government body), and resist all outside interference in the labor movement and national life of the Philippines (which means there must be no contact with the international revolu- That the services of these gentlemen have been recognized is seen by the sympathetic way in which the bourgeois press support all their efforts, while rabidly attacking all militant elements and inciting the reactionary forces in the country to perse- cute the left wing. . 2 The recent developments and the increased opposition between the © é 4 . wld t : enhancing the exploitation | ees 2 SIE Central ¢ By Mai! (in New York onty) By Mail (outside of New Worker >t y of the T SUBSCRIPTION RATES: $8.00 a year York); $6.00 a year; $2.50 three months $4.50 six months; $2.00 three months 33.50 six months; WILL AVENGE OUR DEAD By Fred Ellis ELLA MAY WIGGINS | CLAS Hi) ° oc Ts. ? et PIGHTER. R by 4 Poe, Cel ae 4 § igs oem, ELLA MAY WIGGINS, Gastonia mill worker, widowed mother of five children, murdered by Manville- Jenckes gunmen, Sept. 14, 1929. z . The International Situation and Tasks of the Communist International Report of Comrade Kuusinen AT THE TENTH PLENUM OF THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OF THE COMINTERN I believe we should more than ever devote our attention to the struggle on questions of wages and working hours. We must place the question tegy of surrender that is constantly pursued by the reformists, the workers are frequently confronted with a desperate situation. The Guestion of “to fight or not to fight” becomes ‘the question of “to be or not to be” for the worker. If the masses hesitate on this question, the Communists should not make the least concession to the surrender strategy of the reformists. The latest concession wou! paralyze the radicalization of the masses. We must encourage the masses to take clear decisions. Thus the masses will soon take up independent eco- nomic movements, without the reformist leaders, and partly in spite of them. The masses need and are looking for new leaders to organize and to guide their struggles. If the Communists begin to hesitate on the question of developing the economic mass strikes, or if they attempt to replace such a fight by a policy of revolutionary phraseology and semi-reformist practices, they are going to lose their hold upon the revolutionary movement. They are going to divert the leftward move- ment of the masses from the path of revolutionization to the path of reformism. A further stage in these fights (these stages must not necessarily be conceived as chronological sequences) consists in that the co action of the bourgeois state in alliance.with the employers’ associa- tions, with the trusts, etc., imports a political content to the economic struggle of the workers. The fascisation of the state authority and of the dominant bourgeoisie as a whole, beginning with the factories in which open imperialist war preparations are carried on, is a powerful factor in emancipating the masses from the spell of pacifist illusions. The social-fascist practices of the reformists furnish the necessary object lessons to the masses. The old mechanism for the maintenance of “social peace” (social insurance, etc.) is becoming more and more discarded. Nevertheless, certain new methods of corruption may be tried out here and there. In France, for instance, a suggestion was made by a certain bourgeois politician that shares of industrial enter- prises be distributed among the trade unions—of course, not among the Unitary, but among the reformist trade unions—in order to get them interested in the profits of the business. (A voice: They are talking about this also in Germany!) This shows the efforts of the bourgeoisie to devise new methods for corrupting a section of the work- ers. This, however, does not yet constitute the distinguishing feature of the present period. The whole course of the bourgeois class domina- tion is directed towards replacing more and more the old mechanism of the maintenance of “social-peace” by the methods of fascist terror. The political effect of the reign of terror upon the working class is not so uniform as was the effect of the illusions. As a matter of fact, the problem of mass activity under the fascist regime should be studied more closely than hitherto; because we have to learn to organize the mass movement in such forms as would be able to survive the white terror, which would render it most difficult for the dominant regime to crush the mass movement, to deprive the masses of their leaders, to exterminate the revolutionary leadership, and so forth, On the one hand, terror as a system of government may render the mass: ‘| passive to a certain extent. Even good revolutionary workers may or some length of time remain passive in the legal organizations, i. the re- formist trade unions, ete., under the pressure of the reign of terror; while the situation is not yet acutely revolutionary, they are not pre- pared to make such big sacrifices as they would be called upon to make when the final fight comes and which they will then be prepared to make. On the other hand, the reign of terror leads to a rise in the spirit of class hatred among the masses. But there is an important point to be noted in this connection. Every reaction may lead to the shattering of reformist illusions among the masses and to an increase of their class hatred. These are essential elements in the revolution- ization of the proletariat. Yet this does not explain everything that is new in the character of the present mass fights. The regime of terror can make the masses conscious of the necessity for the political fight, but this does not yet mean the starting of the fight itself. This does not yet explain the enthusiastic desire for political mass fights ob- served in connection with recent mass actions, even with those of an opportunist and revolutionary tendencies make it imperative for the left wing to stand together solidly and give a clear lead in carrying out its policy, reinforcing achievements already gained and struggling actively to unify the labor movement on the basis of the class struggle, urging an eight-hour day, increased pay, recognition for the unions, protection of female and child labor, both in town and village, against the inhuman exploitation of the agricultural workers and: the poor peasantry, thus extending their influence among the workers (news at hand shows that half of the organized workers have already affili- ated to the new Labor Congress), organizing the unorganized and tak- ing up their place in the vanguard of the struggle for independence, ears | ~-ALVAREZ, " hs; Feri of the seven-hour day in the foreground. Owing to the stra- | economic character. This desire for the political class struggle, this tendency towards stormy extension of the battleground, this aggressive spirit of the proletarian mass fights is the most important new trait io be observed. Not everywhere is this new trait clearly expressed, byt it has beef already quite clearly signalized by the actions which have taken place in Berlin, in the Ruhr, in Lodz, in Bombay. e The Shaking of the Relative. Equilibrium. What are the objective causes to this new character of the mass fights? I should like to draw a comparison with the war period. The bourgeois class terror was naturally strongest at the commencement of the war, when the front of all the imperialist powers was still strong. At that time, the radicalization of the soldiers was an exceedingly dif- ficult process. But as soon as the difficulties started at the front, as soon as the soldiers began to be aware of a weakening in the situation, a different spirit asserted itself both at the front and in the rear. The same is shown by examples from the Russian Revolutions of 1905 and 1917, as well as by the German revolutionary events of 1918-19 and 1923. Similarly, such a semi-reformist, semi-revolutionary mass move- | ment at the shop steward movement in England in 1919-1920 was ob- viously connected with the objective crisis experienced then by the ruling system of British imperialism. If the situation were today in- deed,as appraised by Humbert-Droz and other conciliators, if capitalist stabilization were,really getting stronger, then the present semi-revolu- | tionary, militant character of the mass movements would be a puzzle, The thesis of the German conciliators says: “Economic strength- ening of the present basis of the relative stabilization, and consequently of the political might of the bourgeoisie” (December Memorandum by Ewert and others). Even if they go on to “recognize” generally the existence of the capitalist contradictions, this is of no political signi- ficance, if there is really an economic strengthening of the basis of the political might of the bourgeoisie going on. But we know this to be utterly wrong. This is also in sharp contradiction to the line of the Sixth World Congress. We know that owing to the intensification of the essential antagonisms during the present period, the relative stabi- lity gained by the capitalist world during the second post-war period is becoming more and more undermined. In my opinion, “relative equi- librium” is a more appropriate term than “stabilization.” Lenin spoke at the Third World Congress about a “relative, temporary equilibrium.” The talk about “stabilization” came into vogue in our political language enly in connection with the stabilization of the currency of the different countries. Of course, one may use also this term, if properly applied and correctly understood. For instance, if one speaks about “contra- dictions of stabilization” this is rather a vague expression, and when German conciliators speak even of “structural changes inside of stabil- ization,” is is so sophisticated that I fail to grasp this mysterious stabilization; it appears almost like a modern hotel “inside” “of which everyone may accommodate himself as he sees fit. According to the conception of Humbert-Droz and Ewert, the objective character of the present period is confused with the subjective stabilization aims of the bourgeoisie in the different countries and with the pioys wishes and illusions of the social democracy. To be sure, the bourgeoisie may even now attain some partial success here and there by stabilization. Yet it is exactly the specific character of the present period that even these “achievements” of the bourgeoisie serve only to itensify objectively the fundamental contra- dictions of the capitalist system, to set into motion ever-stronger coun- ter-forces on a national and international scale, and thus to accelerate the tremendous clash. Certainly the relative, temporary equilibrium of the capitalist world is not yet liquidated. This will be accomplished only at the end of the process which is going on during the present period. But’ the dynamics of development in the present period are fundamentally different from those of the second post-war period, The Character of the Present-Day Mass Struggles. It is highly characteristic that the present process of the shaking of the capitalist equilibrium has been better understood by the large proletarian masses than by some opportunistic Communists (like the conciliators), The masses have an instinctive feeling that the revolu- tionary struggle is now possible. There is now no longer any hesita- tion whether to fight or not to fight; there is not even the heavy consciousness that the fight is objectively unavoidable even if hopeless; there is rather an eagerness for the fight, for the political class strug- gle, for the political mass strike. During a stabilization period of capitalism the center of gravity in the struggle of the masses—and this is a vast difference—lies in the immediate partial demands. The linking up of these partial de- mands with the strategical goal of the revolutionary movement during such a period is to the large masses more or less a matter of indif- ference, or a sub-conscious objective. This linking up of the ultimate revolutionary slogans with the immediate demands is chiefly of propa- gandist importance during such a period. at } , Also during the present the magaes sxe senggting for |" CRE 1g Be SR ee rahe ae lua Translated by Brian os MAY 4 E L Ee HENRI BARBUSSE “1 Say It Myself” by Henrs Barb: P. Dutton & Cow Ince New ¥ | t Reprinted, by permission, from published and copyrighted by E. CONTAMINATION * A Bulgarian among a group of Italian refugees who are working on the Cote d'Azur under the eyes of the Italian police tells a story of his native land—a village swathed in snow, a church tower, children playing. ety. 2 soPHE father,” he said, “was standing there, standing on his big feet, flat as platters, and first he watched the children at play. Then off he went, on his big feet. “The children wore little sheepskin caps, some grey, some black. Some new, others worn bare in places. They had soft leather leggings and shoes like leather stockings. When they called té one another by name they said ‘Mentcho, Netcho, Dinkcho.’ ” “What were they playing at?” f “Ah, that was it. They were playing at the big, important things they had heard talk of. They were playing at Life with a big LY “Children,” sententiously remarked a Piedmontese who spoke French, “are more intelligent than men, because they know less foolish- ness. But they’ve one big fault; they imitate men as much as they can!” The Bulgarian, who had waited till the Piedmontese had done talking, went on: 3 “A few years back—and several of these children were only just crawling about and making noises then—they were playing at war. Armies, generals, gun firing, beating of negasants by loud-voiced, gold- striped soldiers.” . . ® (Qe this Bulgarian had the gift of expression. “You're a school teacher?” x ‘ “Yes. But they had heard that the war with foreign countries was over. So war games were no longer the thing. They were playing at police games now, instead of war games. They had herad tales of the dire deeds of vengeance done by police officers and judges, men who search houses in towns and make their appearance in villages, like the destroying Angel in the Bible story; and these tales had had an exciting effect upon their imaginations. “Now there were three criminals who were far more famous than all others; the three men guilty of the outrage in the Cathedral: Koeb, Zadgorski, and Friedmann. These were the three, but Marco Friedmann was the tallest in height, and they talked especially of him. “Thousands of men had been killed by the police heroes after the bomb exploded in the Cathedral. But they hadn’t, unfortunately, taken photographs of all that, whereas Friedmann’s trial and end had been cinematographed. The children knew that fifty thousand people had been there to see the ceremony and that it had been like a great festi- val. They also knew all that Friedmann had said: how in court, he had never stopped crying: “I am innocent.” * * . “a7 Lee the journalists’ cameras had recorded his smallest movements at the last, up to the very moment when the gods of justice had hung him, under the spectacled nose of the Public Prosecutor, before. Pove and officials and officers and soldiers and fifty thousand good people. “It was this final scene that the children were acting. The prose- cutor was there, the general, the Pope and the executioner, and Marco Friedmann. The crowd was the only missing thing, but, after all, they had what really mattered. “The boy who was Marco Friedmann wasn’t very pleased. He frowned and looked gloomy, and that was all to the good, “The royal judge clenched his fists and pursed up his lips. His forehead had a wrinkle. He had put spectacles on to be more like the judge. “And now the pigmy Friedmann grew excited and began shout- ing: ‘I am innocent!’ “Silence, scoundrel!’ cried the Pope, tapping the ground with his foot. But he didn’t dare to move too much, for fear of getting his legs mixed up in his Pope’s skirts. “The children had chosen this place for the trial because there was a swing standing there and it did capitally for the gallows. “‘Hang him!’ they cried. “They did just what the picture postcards, newspaper photo- graphs and cinema had shown was done. They tied a rope to the hook up top and round the neck of the condemned; they put a sack on his head. They made him get up on the table. . 8 6 ae sentence was read, The prosecutor took it from the clerk’s hands and read it himself. He read it really well, emphasizing his words, and trembling a little because these were serious doings (and the sentence was the real sentence, carefully copied out). “‘Away with the table!’ they said. 1 “The moment was such a solemn one that his majesty’s prosecu- tor threw away the cigarette he was smoking like a man. “Marco Friedmann’s tiny legs kicked about in the air. “And they hanged him. “They cut him down. But a few moments had come between, strangely exciting, voluptuous moments, and when they cut him down,. there was nothing left but a poor little puppet of flesh and blood. The face underneath the sack, which was not easy to take off, was so still and so white, so like the snow, that they let him drop to the ground and ran away, “The father was a long way off at work. No one knew anything till the evening.” The other Bulgarian, with the blue muffler, now began to speak, and the sound of his voice seemed familiar. ee 1 4 KNOW that story about the child actually hung by his playmates. and there wasn’t any snow. But it didn’t happen exactly like that. It was in June or July, It was in the country, near Bourgas.” “Not a bit of it,” interrupted the third Bulgarian, with the black muffler for colors. “It was in a suburb of Pleven that all this hap- pened. A little boy was found, stiff as a log; ‘his playmates had hanged him for fun, to copy grown-up people as far as they could.” “What's all this?” one of us asked. Explanations followed, and it appeared that the first was right, the second wasn’t wrong, while the third had told the strict truth. There were several more or less similar episodes, and all ended the same way. The true story happened several times over. It is more than true, then. And what is no less true, is the contamination spread by sav- agery, and mad and criminal acts. (Tomorrow: And We Were Celebrating Peace.) | their immediate everyday needs. This we should constantly keep in mind when framing our tactics. Nevertheless, the struggle is now no longer limited to these immediate partial demands; there is now a distinct and strong tendency for the struggle to go beyond these limits. Rs A fight is now waged even in such cases when the workers know that. th the immediate fulfilment of the demands cannot be attained; a fight is S waged in order to show the power of the proletarian class, in order 2 to avoid surrendering to the class enemy like abject slaves. Force against force, such is the sentiment among the large masses of the ry workers. Eventual partial defeats during this period no longer cause KS a mood of depression, and heavy defeats are borne even more easily than cases of surrender without a fight. (Hear, hear.) The masses are now raising more or less consciously the demand for fortifying the fighting positions in order to prepare for a new trial of strength against the class enemy. This is the character of the proletarian offensive which is now more or less clearly revealed in some of the mass fights, as against the defensive character of the movement during the second post-war Ks priod. Whether the fight is based directly upon the slogan of higher tio ‘wages, or upon resistance to wage reductions, is immaterial to the die character of this movement. The approaching revolutionaty upheaval ai is foreshadowed—I should say—by a certain red glow upon the horizon, i This arouses the fighting spirit of the masses, the eagerness for poli- fre tical mass fights. This is connected also with the growing revolu- tionary attraction of the Soviet Union for the large masses of the proletariat in the capitalist countries. The Soviet Union is a living, “ } grand, gigantic example that the Socialist revolution and the prole- tarian dictatorship are possible. Hence, the great interest now shown i in the Socialist construction efforts of the Russian proletariat. the The revolutionization of the mass movement is a process which the has just started, or has reached only the middle of its course; but it I is bound to develop farther. The farther it develops, the more it will of mmunist Parties, if only the me lead to the growing influence of the Co: A by the Gomm “