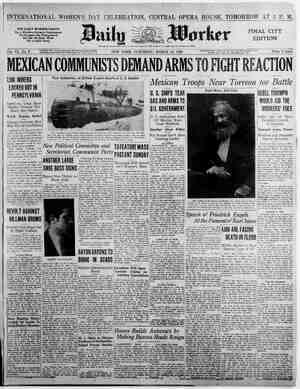

The Daily Worker Newspaper, March 16, 1929, Page 6

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

DAILY WORKER, NEW YORK, SATURDAY, MARCH 16, 1929 . SUBSCRIPTION RATES: By Mail (in New York only): 58.00 a year $4.50 six months $2.50 three months By Mail (outside of New York): $6.00 a year 3.50 six months $2.00 three months Address and mail all The Daily Worker, Squ Published by the National Daily Worker Publishing Association, ¥y checks to Union ROBERT,MINOR . WM. F, DU! New Yor e, All Revolutionary Traditions Belong to the Communist International The month of March is replete with anniversaries sig- nificant to the revolutionary labor movement. On March 18, 1871, fifty-eight years ago, the Paris Com- mune, the first appearance in history of the dictatorship of the proletariat, was proclaimed. On March 14, 1883, the great founder of the Communist Party, Karl Marx, died. On March 14, 1917, the Russian czar was overthrown. From March 2 to March 7, 1919, occurred the first Con- gress of the Third International—the Communist Interna- tional—in Moscow, which had become the capital of the vic- torious Russian proletarian revolution. $ All of these “events of March” are inseparably bound together in the history of the long struggle of the enslaved working class for freedom.- And the last-named of these events—the founding of the Communist International just ten years ago—constitutes the embodiment of the whole of the revolutionary traditions that are called to memory by the other anniversaries. s The vevolution of the Paris working class which founded the Commune was a direct historical ancestor of the revolu- tion of the Russian workers and peasants of 1905 and of the subsequent, successful revolution of October, 1917. The Paris Commune was in a real historical sense the predecessor of the present dictatorship of the proletariat of the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics. In the Paris revolution of 1871 were active members of the International Workingmen’s As- sociation, the First International, of which the present Com- munist International is the direct heir and the successor on an immensely developed scale. ‘ Marx contributed to the world proletarian revolution the tremendous work which laid the foundation of the science of proletarian revolution embodied today in the Communist International. The founder of the “Communist League” which issued the “Communist Manifesto” in 1848 is in fact also the founder of the Communist International. Vladimir Ilyitch Lenin, under whose leadership the proletarian revolu- tion was won and the successful dictatorship of the prole- tariat established, and whose strong hand guided the Com- munist International into life, did much more than the mere “revival” and “application” of Marxism. For Lenin was himself the creative genius of revolution who ranks with Marx in the building of the revolutionary science. The per- iod of imperialism, the last stage of capitalism, the period of the proletarian revolution, bringing forth unprecedented phenomena, found in Lenin not a mere repeater of knowl- edge long ago learned, but another revolutionary giant of the stature of Marx—a creative leader capable not only ‘of the complete mastery of all that Marx had given, but also capable of carrying that science forward to unprecedented development on both the theoretical and the practical plane under the new conditions of imperialism, world-war and the breaking of the imperialist chain by force of revolution at its weakest point.. It is thus that revolutionary Marxism, not only as Marxism, but also as Leninism, found its triumph in the victorious revolutionary Soviet Union. It is truly said that Lenin was the founder of the Com- munist International, and it is just as true that the historical origin of the Communist International dates back to Marx who shares with Lenin the title of its founder. We recall the efforts to claim the traditions of Marx as belonging to the social-democratic parties of the Second Jnternational, in op- position to what the social-democratic traitors called the “Asiatic Socialism” of Lenin as embodied in the Communist International. But the hideous lie burns the lips of those who tell it. Even the yellow sociai-democratic traitors themselves hardly dare any longer to maintain the shameless pretense that the revolui‘onist Marx belongs to the counter-revolution- ary party of Hillquit and Cahan, Scheidemann, Noske, Muel- ler and MacDonald, and today their papers are full of “ex- planations” that Marx is now “obsolete.” Marx belongs to the Communist International. The overthrow of the Russian czar, preceding the ’prole- tarian overthrow of the Russian bourgeoisie, would have re- sulted in nothing even resembling the liberation of the Rus- sian masses, if it had not served as the starting point for the proletarian revolution. Its traditions also are meaning- less except to the history of the Communist revolution. Throughout the world it is customary for class-conscious workers to demonstrate on the 18th of March in memory of the Paris Commune. longer a dead thing of tradition alone! The Paris Commune actually lives in the form of the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics. The slightest word of glorification of the heroic deeds of 1871 becomes shameful hypocrisy unless coupled with honor to the “Paris Commune” of today—the Soviet Union. Would you live again in the traditions of the bar- ricades of Paris—defending the Commune from the armies of reaction? Well, then you have your chance to do ‘this, not in stupid make-believe, but in deeds. For the living Union of Socialist Soviet Republics is facing attack today. The imperialists are plotting war for the destruction of the Union of Socialist Soviets. Defend it with your life—work- ers of all countries! Would you do honor to Marx? Then do honor to the living organization of proletarian revolution which is in the truest sense founded by Marx—the Communist International. And not in words, but in revolutionary practice—by be- coming a member of the Communist Party of the United States of America, the section of the Communist Interna- tional. The Communist International is the world-Party of the proletarian revolution. In it are found the glorious tradi- tions of all of the history of the working class struggle. In it is found the only leadership that anyone can even dream _ of as leading in the revolutionary overthrow of the imper- jalist capitalist ruling class. It embodies the leadership of the proletariat together with the leadership of the revolts of the colonial oppressed peoples of the world. The Communist International is your world-Party, if you are a worker. ~ ~ Join it today. But today, the Paris Commune is no | Personal Recollections of Marx | By PAUL LAFARGUE. (The following is from an article by Paul Lafargue, son-in-law of Marz, entitled “Personal Recollec- tions of Karl Marz.” It tells of Marzx’s intellectual life, his literary interests, and his methods of work.) * * * At my first visit, when I saw. him in his study in Maitland Park Road, he wasso me, not the indefatigable and unequalled political agitator, | but the man of learning. This room has become historical. From all | parts of the civilized world those | who wished to consult the master of | | socialist thought flocked to it. | Any one who wants to realize the} intimate aspects of Marx’s intellec-| tual life must form a mental picture of this workroom. It was on the | first floor, well lighted by a broad | window looking on the park. The | fireplace was opposite the window, and was flanked by bookshelves, on | the top of which packets of news- | Papers and manuscripts were piled up to the ceiling. On one side of the window stood | two tables, likewise loaded with mis- cellaneous papers, newspapers, and books. In the middle of the room, where the light was*best, was a small THE “IDES OF MARCH” + Larfargue Writes of Marx’s Intellectual Life and Methods of Work Year after,year he would read Aes-| chylus again in the original text, re- garding this author and Shakes-| peare as the two greatest dramatic geniuses the world had ever known. For Shakespeare he had an un-| bounded admiration, He had made an exhaustive study of the English playwright whose lesser characters, even, were familiar friends. He rested his mind by pacing up and down the room, so that between door and window the carpet had been worn threadbare along a sharply de-| fined track, like a foothpath through | a meadow. Sometimes he would lie} down on the sofa to read a novel,| and had often two or three novels| going at the same time, reading| them by turns—for, like Darwin, | he was a great novel-reader. He had| refuge in it during the most painful | sponsibility. a preference for eighteenth-century | novels, and was especially fond of} In the days of his wife’s last ill-| thenticity there could be the slight- Fielding’s Tom Jones. Among modern novelists, his fa- vorites were Paul de Kock, Charles} Lever, the elder Dumas, and Sir| Walter Scott, whose Old Mortality | he considered a masterpiece. He had/ riod he wrote an essay upon the in-| worked over it again and again, and | a predilection for tales of adventure | finitesimal 3 |tained were so appalling. Some de-| Marx was moved by a very differ- By Fred Ellis | due to carelessness, or to show that ea of his demonstrations were based on facts which could not be corrobo- | rated. | Thanks to his habit of consulting the authors he chiefly prized: Push-| originals, he would often quote au- kin, Gogol, and Shedrin. thors whose names were known to But his main reason for learning| very few besides himself. Capital Russian was that he might be able| contains a number of such quota- to read certain official repofts —| tions — so many that it might be which the government had suppress-| supposed they were introduced to ed because the revelations they con-) make a parade of learning. But voted friends had managed to pro-|ent impulse. He said: “I am per- cure copies for Marx, and there can| forming an act of historical justice, be little doubt that he was the only|and am rendering to each man his western economist who had cogni-| due.” It seemed to him obligatory zance of them. ‘ to name the author, however insig- Besides the reading of poetry and| nificant and obscure, who had first novels, Marx had recourse to an-| expressed a thought, or had express- other and very remarkable source of| ed it more precisely than any one méntal relaxation, this being math-| else. ‘ ematics, of which he was exceeding- ly fond. Algebra even gave him mo- ral consolation; and he would take) moments of.a stormetossed life. ness, he found it impossible to goeon| with his ordinary work, and his only escape from the thorght of her suf- ferings was to immerse himself in mathematics. At this distressful pe- calculus, Professional |and plain writing table, three feet) and humorous stories. The greatest} mathematicians who have read ‘it,| by two, and a windsor armchair. Be-| tween this chair and one of the| bookshelves, facing the window, was} a leather-covered sofa on which} Marx would lie down to rest occa-) sionally. On the mantelpiece were more| books, interspersed with cigars, box-| es of matches, tobacco jars, paper- weights and. photographs — _his| daughters, his wife, Friedrich En- gels, and Wilhelm Wolf. Marx was} a heavy smoker. “Capital will not} bring in enough money to pay for the cigars I smoked when I was writing it,” he told me. But he was| still more spendthrift in his use of| matches. So often did he forget his pipe or cigar that he had constantly | to be relighting it, and would use up a box of matches in an imcredibly short ttme. He would never allow any one to | arrange (really, to disarrange) his |books and papers. The prevailing | disorder was only apparent. In ac- | tual fact, everything was in its prop- | er place, and he could put his hand | on any book or manuscript he want- \ed. When conversing, he would of- ten stop for a moment to shoW the | relevant passage in a book or to find numerical reference. He was at one with his study, where the books and papers were as obedient to his will ‘as were his own limbs. He disdained appearances when arranging his books. Quarto and oc- tavo volumes and pamphlets were placed higgledy-piggledy as far,as size and shape were concerned. What interested him was their content. To him books were intellectual tools, not luxuries. “They are my slaves,” he would say, “and must do as I bid them.” He had scant respect for their form, their binding, the beauty of paper or printing; he would turn down the corners of the pages, un- derline freely, and pencil the mar- gins. He did not make notes in his books, but could not refrain from a ques- tion mark or a note of exclamation when an author kicked over the trac- es. His system of underlining en- abled him to refer back to any de- sired passage. Every few years he would re-read his notebooks and sa- lient passages in the books he had read, in order to refresh his mem- dry—which was extraordinarily vig- orous and accurate. From -early youth he had trained it in accord- ance with Hegel’s plan of memoriz- ing verses in an unfamiliar tongue. He knew much of Heine and Goe- the by heart, and would often quote these poets in conversation. Indeed, he read a great deal of poetry, in most of the languages of Europe. | and follies. masters of romance were for him| Cervantes and Balzac. Don Quizote| was the epic of the decay 6; chival- | ry, whose virtues were depicted by| the rising bourgeoisie as absurdities | . His admiration for Balzac was so) profound that he had planned to} maine as soon as he should have|Teached a form in which it could) joaye them behind him unfinished. finished his economic studies. Marx looked upon Balzac, not merely as the historian of the social life of his} time, but as a prophetic creator of| character types which still existed | only in embryo during the reign-of | Louis Philippe, and were not to un- dergo full development until the days of the Second Empire, after Bal- zac’s death. . Marx could read nearly all the leading European languages, “and could write three (German, French. | and English) ina way that aroused | the admiration of all who were well| acquainted with these tongues; and he was fond of saying “A foreign language, is a weapon in the strug- gles of life.” He had a special talent for lan- guages, and this was inherited by his daughters. He was fifty when he began to learn Russian. Although the dead and ,the living languages al- ready known to him were of no help in the mastery of Slavic roots, he had made such progress in six months to to be able to enjoy reading in the original the works of Scientific Thinker and Revolutionrry Fighter By G. PLECHANOFF. (From angarticle written in 1903.) The thirty-fifth number of “Iskra” appears on the twentieth anniver- sary of the death of Karl Marx, to whom tée first place must there- fore be allotted. If it is true, that, the great international working-class movement was the most remarkable social phenomenon of the nineteenth century, it follows that the founder of the International Workingmen’s Association was the most remark- able man of that century. A fighter and a thinker rolled into one, he not only organized the forces of the CS army of the workers, but forged for that army (in collaboration with bis faithful CJ a | of many lands. describe it as being of the first im-) portance, and it is to be published in} his collected works. { In the higher mathematics he could trace the dialectical movement} in its most logical and at the same} time in its simplest form. Accerding| to his way of thinking, a science was| | write a critique of La comedie hu-| not properly developed until it had} make use of mathematics. | Marx’s library, comprising more than a thousand volumes laboriously | got together in the course of a life-| time of research, was insufficient for his needs; and for many years he was a regular attendant at the Brit- ish Museum Reading Room, whose catalogue he greatly prized. Even his: opponents are constrained to} admit that he was a man of pro-| found and wide erudition; and this not merely in his own specialty of} economics, but also in th® history, philosophy, and belletristic literature | Marx was an extremely conscien- tious writer. He never gave facts or figures which he could not sub- stantiate from the best authorities. In this matter he was not content with second-hand sources, but went always to the fountain head, how- ever much trouble it might: entail. Even for the verification @f some subsidiary item, he would pay a spe- cial visit to the British Museum. That is why his critics have never been able to convict him of an error friend Friedrich Engels) the power- ful spiritual weapon with whose aid it has already inflicted namny de- feats upon its enemy, «nd will ere long win a ‘complete victory. If socialism has become scientific, we owe this to Karl Marx. Further- more, if awakened proletarians are now fully aware that the socfl rev- olution is an essential preliminary to the final deliverance of th® work- ing class, and that this revolution must be brought about by the work- ers themselves; if they now show themselves to be the implacable and indefatigable enemies of the bour- geois system of society — these things are due to the influence of ‘a thorough study of ‘it. | would have been most distressing to him to show one of his manuscripts | scientific socialism, | His literary conscience was no less strict than his sense of scientific re- Not merely would he never mention a fact of whose au- est doubt, but he would not allude to a topic at all unless he had made He would not publish anything until he had until. what he had written seemed to him satisfactory in point of form. He could not bear to offer half- finished thoughts to the public. It before it had. been finally revised. This feeling was so strong in him that he said to me one day he would rather burn his manuscripts than His methods of work often involved him in tasks enormously more ardu- ous than the readers of his books could imagine. For instance, in order to write the twenty-odd pages of Capital dealing with British factory legislation he had consulted a whole library of blue-books containing the reports of special commissions of enquiry and of the English and Scottish factory inspectors. As the pencil markings show, he read them from cover to cover. . He regarded these reports as some of the most important of the docu- ments available for the study of the capitalist method of production; and he had so high an opinion of the men who had made them that he de- clared it would be hard to find in any other nation “men as compe- tent, as unbiased, and as free from respect of persons as are the Eng- lish factory inspectors.” This re- markable tribute will be found in the. preface to the first volume of Capital. Copyright, 1929, by Internationai Publishers Co., Inc. BILE HAYWOOD’S == BOOK Haywood, a Captive, Rushed by Special Train to a Death Cell at Boise, Idaho, Charged With Murder All rights resesved. Republica- tion forbidden except by permission. In previous chapters Haywood told of his early life as miner, cowboy and homesteader in the Old West; of his years as union miner in Idaho; his election to head of: the Western Federation of Miners; its great strikes in Idaho and Colorado; the formation of the I. W. W. in 1905; of the explosion which killed Steuenberg, ex- governor of Idaho and how he, Moyer and Pettibone were kidnapped in Denver in February, 1906, and put on a special train under guard, bound for Idaho, charged with the murder. Now go on reading. * By WM. D. HAYWOOD PART 61. ° ee E had a car to ourselves except for the guards, one of whom was Bob Meldrum from Telluride. I have never seen a human face that looked so much-like a hyena. His eyes were deep-set and close together. His upper lip was drawn back, showing teeth like fangs. The deputy warden of the Idaho penitenti-ry came up and spoke to us. In the course of his talk, he teld us.many of his exploits in arresting dan- gerous men. We listened for want of better senter- tainment. Later Bulkeley Wells came into the car with a bottle of whisky and asked us to have a drink, which we did, handling the glass rather awkwardly on account of the handcuffs. We found out from him that we were on a special train and that we would arrive in ‘Boise the following morning. We were going at terrific speed. The engine took on coal and water at small stations and stopped at none of the larger towns along the route. When we arrived at Boise we were put into separate conveyances, At the depot a crowd had gathered, I saw among the people a storekeeper whom I had known at Silver City. He spoke to me genially. a *e. * 'E drove to the penitentiary. There was the sign over the gate, Admittance Twenty-five Cents, but as before, when I had come to see Paul Corcoran, I was admitted without charge. In the office we signed a paper authorizing the warden to open any mail that came for us, and I requested that a telegram be sent to John O’Neill in Demver, asking him to forward my personal mail to the penitentiary. I couldn’t help noticing the look of surprise that went over the face of Bulkeley Wells at this;ghe could not have expressed more plainly in words his astonishment that I had nothing to hide in my personal mail. After being searched in the office we were taken into the prison ang put in the death cells. I have always thought that we were put in the death cells in order to condemn us in the mind of the. public before we were tried. While we were there I was constantly under the eyes of the death-watch, who sat immediately opposite my cell. Many times I thought, “There are moments when one likes to be alone.” . * 8 ® ¥ AS we entered this corridor and our numbers were called out Pettibone quoted, “There is luck in odd numbers, said Barney McGraw!” My number was nine, Moyer’s eleven, and Pettibone’s thirteen. Through the window that faced the rear wall I could see what I after- ward learned was the death-house, where the condemned were hanged. ~ Here we were in murderers’ row, in the penitentiary, arrested + without warrant, extradited without warrant, and under the death watch! We had been-kidnapped in the dead of night and did not know whether our lawyers were aware of our destination. Certainly no one could have expected that we would be put in the penitentiary without a hearing, without a trial, or even the semblance of an investi- gation. They held us there for nearly three weeks. We later found out that Governor Gooding had said that we would “never leave the state alive.’ This remark piled up a lot of tribulation for the gov- ernor. He got thousands of letters of condemnation from all over the world. One person contrived to mail him a letter from a different ‘city every day in the year. We were told that he got six post-bags of mail in one day. But in spite of this’ he was later elected United States Senator. * 8 oN either side of my cell were men‘who had been condemned to death. Immediately in front of me was the death-watch with his chair propped back against the wall. He did not seem to be interested in the men he was put there to watch. He seemed to keep his veno- mous eye fastened upon me except when the cell was opened to take out the bucket, or at meal-hours when he would turn the food over im | the plates and then slip it under the door. It is difficult to realize that under these circumstances I could get news from outside. But the Boise penitentiary was no exception to prisons in general. The pris- oners had a code language in which they could discuss almost any- thing. Messages came in and went out. I cannot tell you how, be- cause there are men still in Boise who were there when I was, twenty years ago. os “28 «@ QNE day I saw a strip of paper coming through the interstices of the front bars from the cell on my left. I got up and grabbed it, but pulling it too hard I tore it in two, I kept the part I had concealed in my hand until I could find a moment to read it. The guard, who had prcbably turned his head away for a moment, thought that I had slipped the message to the other man. He called wa “trusty” and sent for the warden. In a few minutes there was a general commotion. They dragged out the man and threw out his bedding and bunk, and examined everything minutely. Finally they pulled out the bucket, and found the charred remains of a bit of paper, a part of the message he had tried to slip me. The little bit of paper I got was blank, Members of Italian Consulates Act as Agents for Fascisti PARIS, (By Mail).—It is a well- known fact that the diplomatic representatives of the fascist gov- ernment work quite openly with the local fascists and interfere very definitely in the affairs of the coun- tries to which they are accredited without any protest being made by the governments in question. A new case has’ been reported, this time from Liege. An anti- fascist Italian immigrant in Bel- gium married a Belgian girl, In order to obtain identification papers, the young woman went to the Ital- ian consulate and thete she was in- formed quite simply that if her hus- band ‘would give up his anti-fascist opinions and join the 1 Fascist League, both he and she could have all the papers they required, a The warden came up to my cell and said: “Haywood, while you're here you are under the rules of this penitentiary. I do not want you to attempt to communicate with any one,” I replied: “You needn’t be alarmed about that. I don’t know wl:om | you have got planted around here.” s © « Artes awhile he came back with ‘a box of cigars that had been ser] «to us*from town by some friend. The cigars had been taken oft, of course, and the box had been examinetl. He was going to hand them through the bars but I told him to give me a few and take th, / rest to the other boys. ‘ ; ; «When our lawyers got on the ground, they raised such. a hulla. balloo about our being in the penitentiary that we were transferred to the county jail at Caldwell. The morning we left for Caldwell we ate | breakfast in the prison kitchen, with a guard at the elbow of each of us, It was the first meal we had eaten outside our cells, | : . In the newt instalmegt Haywood writes of his transfer to the’ Ada County Jail at Caldwell, Idaho; of the “kangaroo court” and meeting, unexpectedly, with an old acquaintance—but hardly a| | + friend, The graphic story of “Big Bill” Haywood is an invaluable | asset to all who would understand the American labor movement. Get his book free by sending in a yearly subscription, renewal or | extension to the Daily Worker. Send just the regular subscriptio; ‘price and say you want Haywood’s book. i 7