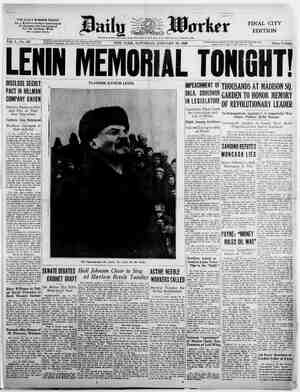

The Daily Worker Newspaper, January 19, 1929, Page 6

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

a corres es Page Six Sone neem oie DAILY WORKER, NEW YORK, SATURDAY, JANUARY 19, 1929 ° SeYe hex LENIN—LEADER OF THE WORLD REVOLUTION Central Organ of the Workers (Communist) Party SUBSCRIPTION RATES: By Mail (in New York only): r $4.50 six months three months outside of New York): $3.50 six months Published by the Worker Publ 2.00 three months checks Address and mail all y Wo . New York, ROBERT MIN to WM. F. DUNNE Editor . Ass, Editor Lenin—and Leninism On January 21, 1924, Vladimir Ilyitch Lenin died. At the age of less than fifty-four years, the death of this greatest leader of our time was the heaviest misfortune to the work- ing class of all countries. Lenin’s hand was the strongest that has shaped history in all time. His work was of a kind and a magnitude which dwarfs comparison with any of his contemporaries. The whole future of human civilization, the decisive currents of present history fall under the influence of that which we call “Leninism.” By its best definition, in the words of Stalin: “Leninism is the Marxism of the epoch of imperialism and of the proletarian revolution. To be more precise: Leninism is the theory and the tactic of the proletarian revolution in general, and the theory and the tactic of the dictatorship of the proletariat in particular.” This definition is correct, as Stalin says, first of all, “because it gives an accurate demonstration of the historical roots of Leninism, which is described as Marxism of the epoch of imperialism ~ -this being an answer to certain critics of Lenin who falsely suppose that Leninism did not originate until after the imperialist war. It is correct, in the second place, because it accurately indicates the international character of Leninism—this being an answer to the social-democrats, who consider that Leninism is not applicable anywhere except in Russia. It is correct, in the third place, because it accurately shows the organic connection between Leninism and the teaching of Marx, describing Leninism as Marzism of the epoch of imperialism—this being an answer to certain critics of Lenin who believe that Leninism is not a further develop- ment of Marxism, but merely a revival of Marxism and an application of Marxism to Russian conditions.” The death of Lenin did not altogether deprive the revolu- tion of Lenin’s guidance. Lenin built too well for that. Heavy as was the blow of his death, great as is the loss of his living participation in our struggles, Lenin left to the world’s oppressed millions the means of utilizing his leader- ship for the gigantic class struggles that are proceeding and will proceed for decades after his death. For Lenin was the founder of the Communist (Bolshevik) Party of Russia, the leader in the creation of the world-party of revolution—the Communist International. His leadership fertilized the vanguard of the working class with the revolu- tionary Marxist-Leninist science, tactics and organizational principles which guide the proletariat to what we must now regard as inevitable victory throughout the world. The first great stronghold of the world-revolution, con- quered under the leadership of Lenin, stands solidly based in one-sixth of the surface of the earth, and just as firmly based in the loyal support of the rapidly increasing class-conscious sections of the working class in all countries of the world. The Union of Socialist Soviet Republics now stands victor against all past efforts of capitalism to destroy it. Its safety has more than a dozen times been confided, and is still confided, to the working class as its watchful guardians in all capital- ist countries and to the Red Army of workers and peasants. The Soviet Union is truly the world-fortress of the revolu- tionary working class; it is not a nationalist “Russia,” it is the Socialist Fatherland of all workers of all countries; its Red Army is ows Red Army—the Red Army of the American workers no less than that of the Russian workers. It was Lenin, above all, who taught us this internationalism. Leninism is not a “peasant-Russia” product, but the high- est development of the science and practice of international revolution. “The dictatorship of the proletariat is the tap- root of the revolution,” said Lenin. Leninism is the guiding light of the proletarian revolution. But Leninism is vastly different from the shallow, chauvin- ist “socialism” of the Second International, which pretends to confine Marxism within the boundaries of the “civilized” (i. e. capitalist) countries. The “Marxism of the epoch of of imperialism” sweeps over the continent of Asia, with its more-than-half of the world’s population, it flows through the heart of Africa to the Congo, through South America, Cuba, Haiti—to Indonesia and the farthest ends of the earth. Lenin showed the oppressed of the world that it is the firm alliance of the oppressed nationalities of colonial and semi- colonial peoples with the industrial proletariat of the capital- ist countries—that this is the revolutionary front which will invincibly overthrow world imperialism. Upon the alliance of the workers with the peasants of Russia, Lenin’s party founded its victorious revolution in that country. And upon the alliance of the world’s working class with the proletarian and peasant masses of those countries exploited by imperial- ism, will be founded the victory of the world revolution, The Chinese workers’ and peasants’ revolution, no less than that of Russia, owes its clarifying light to Leninism. It was of course, not an accident that the first victorious struggle of the world-proletarian revolution occurred in the midst of the imperialist world war. To a “socialist” move- ment betrayed by venal leaders, agents of their own imper- ialist bourgeoisie, Lenin brought the fiery example of a pro- letariat working for the defeat of its own bourgeoisie. Against the treacherous petty-bourgeois program for bringing the war to a utopia of capitalistic “peace,” Lenin brought forth the revolutionary working-class program of “war against war,” the transformation of the imperialist war between nations into the civil war for the overthrow of the bourgeoisie. On this anniversary of the death of our great leader, the capitalist world is more heavily armed than it was on the eve of the last world war. Rapidly the preparations for the coming imperialist war are being carried forward. Will we also do our duty as the Party of Lenin did in 1917? Shall we, the heirs of the revolutionary traditions of Lenin, — be able to purge our Communist Parties of the poisonous in- fluence of bourgeois ideology upon the working class, the opportunism of social-reformism, in time enough that our Communist Party may in the coming imperialist war show itself the true Leninist leader of the working class? To the extent that we Balshevise our Party, to the extent that we mercilessly criticize and eradicate our mistakes, to the extent that we steel our Party in the lessons and practice of Leninism—to that extent we may do honor to our working class cause in the cataclysm that is coming. Leninism is still our guide. . wae sparing of: every ko | | By YAROSLAVSKY. ANY things will be written and many thousands of people will talk of Lenin, of his doings, his words, and his deeds. But even those who never met Jenin, who never saw him or spoke with him, who never had any direct contact with him, felt his power. What was the secret of his influence which was felt in the most out-of-the-way cor- ners of the earth? It was that Len- in managed to be a really great leader and at the same time to re- main a simple, comprehensible man, kin to the most ignorant peasant and {the most backward worker. everything he did. When Lenin spoke to the workers or peasants, his speech was not beyond the scope of the vocabulary of the mujhik and the worker. He spoke a simple language, without strain or affecta- |tion, and it always seemed to the workers and peasants that Lenin guessed their thoughts, that he was speaking of that which they them- | selves were thinking. Wherein lies the secret of this tremendous influence over the work- ers and peasants? It lies in the |fact that Lenin knew how to listen to the voice of the workers and peasants. The Mensheviks have fre- quently remarked that Lenin knew how to issue very simple slogans which the people were capable of junderstanding. This, in fact, was one of Lenin’s strong points: he |knew how to select a simple and comprehensible slogan which united millions of people, a comprehensible \call for a clearly defined p From conversation with indiv workers, from chance talks with | peasant men and peasant women, | |Lenin was able to guess, to sense |what the people were thinking, |what interested them and what |troubled them. In order to under- |stand such people he would’ some- | times speak for hours with the six- teen-year-old son of the worker, |Emelyanov, who was an anarchist, |and regarded himself as being more jleft than Lenin. ‘tion with a Finnish peasant woman, | who said that there was no need to \fear a certain msn with a rifle, be- leause that man with the rifle was ‘a Red Guard, Lenin sensed how the | peasantry regarded the Red Guard. How often did workers and peasants come to Moscow in their great need! | They knew that if they “got to Len- in,” if they wrote to him, Lenin | would do something. He would listen | to them and would help them. When |Lenin spoke to the workers and peasants, they felt that he was speaking from his heart, that he was laying before them his intimate thoughts and ideas. But surpassing all this, was Len- in’s extraordinary modesty. Those who know how he lived abroad must admit that in Soviet Russia, when he became president of that vast Soviet Republic, one-sixth of the territory of the globe, when he was i f the Council of People’s s, he lived in the same simple manner, a simplicity with which no president of any other re- public lives or has ever lived. In his apartment in the Kremlin the most extreme simplicity pre- vailed. Lenin lived just like a skilled, comparatively better paid worker. A simple oilcloth covered the table, the dining room was small and narrow, with plain flower pots on the window-sills. The bedraom was severe, without decoration of any kind and the blankets were plain, almost like soldiers’ blankets. The same simplicity was maintained in his clothing. Lenin was often to be seen with patched boots and threadbare jacket. He was not con- 3 honoring Lenin’s memory we fit ourselves to do |tent with talking of economy; he pin's Work, SD sn aa “kopeck of the He was extraordinarily simple in| From a conversa-| Lenin the Comrade, Lenin the Friend and _ Lenin the Worker Soviet government. In no one were these external qaulities so closely bound up with internal modesty as with Lenin. It was not the humility | which, it is said, is more akin to} pride. Such humility he never pos-| sessed. There was, indeed, a sort of pride in his modesty, but his modesty itself was natural and simple. The peasants remember how he came to the First Congress of Peasants’ Soviets, almost unnoticed, in a threadbare overcoat; you would hardly pay any attention to \him, the peasants said, | Everybody has observed his great care for the needs of his comrades, and this too was the result of Len- in’s extreme simplicity. Everybody knows that he not only knew how to \listen to a comrade, but that he never forgot that it was sometimes necessary to do something for a jcomrade, Everybody who came into close contact with Lenin became aware of this characteristic. I think that at least half an hour of J.en- in’s time was spent on an average every day in attending to the needs lof some comrade or other, arrang- jing for living quarters for him, or, jif he were siek, for medical atten- tion. He insisted that we should look after the health of comrades who had broken down, he was al- a rest or to feed up, or arranging ways sending some comrade off for cures for comrades who were suffer- ing from overwork and overfatigue. He overworked himself in the care of others, but he appeared to do so without strain or difficulty. Lenin’s work was immeasurable. When ,we examine now all he did, all he“wrote and thought, one feels that there is no sphere or corner of our work which Lenin has not illum- inated with his creative mind, which has not received direction from him, which does not bear the mark of his genius. It is difficult to im- agine how one man could do all this work alone. It is true that he was unsparing of his mental energies, that he burned himself out in a slow fire. He was the chairman of the Council of People’s Bureau, the real chairman of the Council of Labor and Defense; he was the chief re- porter at all party congresses and every question at the congresses of Soviets was subjected to his examin- ation; considered by him and tested by him, he endowed it with his ini- tiative and his creative thought. He saw to the execution of every de- By A. B. All their tall words. How from out your Your eyes rivet us LENIN MAGIL, They who hate us, they shall find How we answer hate with hate | And repay them soon or late, How the mountain of your mind Crushes into littleness They shall see How invincible we can be, By your strength made pitiless. They who circle us with night Shall find how sun thru darkness seeps, thousand sleeps with light. Solidarity—the Cuban Workers and Peasants Answer to the Murder of Mella By Fred Ellis | jcision that was taken, he would go| into details, he would investigate everything. But all this required a| superhuman exercise of brain, | nerves and of the whole organism. | And indeed, Lenin wore out his or-| |ganism in 54 years. Perhaps that |powerful personality would have| ‘survived for another twenty or thirty years. If Lenin, five or six years ago, had been asked which he| preferred, to work as he worked, with the concentration of every ounce of energy and to sacrifice ;every drop of his blood for another |five or six years, or to work at a} normal rate for 15 to 20 years, he} would certainly have chosen the| former. | The great force of attraction which Lenin exercised lay in his ex- traordinary endurance, his’ insist-| ence upon principle, i. e., his ability | to insist upon the important and fundamental in the teaching of} |\Communism. One may give way in trifles, one must know how to man-| ‘euver and to retreat, but not give) way on fundamentals. This is how} he treated the problem of Petrograd at the time of the seizure of power: | \“We must at all costs seize and re-| tain the telegraph stations, the telephone stations, the railway sta- tions and above all, the bridges; Let leverything perish, but the enemy | must not be allowed to get through.” | | At such moments, indeed, Lenin} | did not know what it was to retrea' | His endurance and fidelity to princi-| ple were more than once tested in practice when the whole party was} vacillating, when certain of its lead-| ers doubted and wavered. Lenin never | hesitated to break with a comrade if| in his opinion, that comrade was hin- dering the cause of the proletariat. | That was why he was so often re- garded as a sectarian, an extremely intolerant man, a fanatic. His opin- ion was that if the path he had taken was right, it was not such a terrible matter to remain alone for a time, pfovided only that he was convinced that the path he had chosen was the right one. He was sure he would convince millions of others, that he would succeed in convincing the whole party and the whole working class. This simplicity, combined with great modesty, his attentiveness to the needs of the comrades, his tre- mendous capacity for work, his en- durance and fidelity to principle, and the fact that he introduced strict discipline into the party, made Len- in a man capable of victory. Therein lay the secret of his great influence upon us all. We knew that if Lenin wanted a thing, he would stick to it stubbornly until he got it; hé would use every argument, the whole force of his logic, he would cite every fact and take advantage of our owr weaknesses in order to demonstrate his idea and compel us to admit its truth. Soviet Trade Union Delegation to Go.to Amsterdam Peace Meet (Special to the Daily Yorker) MOSCOW, (By Mail).—The Red International of Labor Unions, the Russian Miners’ Union, and the Transport and Metal Workers’ Unions and other unions have been invited to attend the peace confer- ence which takes place at the begin- ning of January in Amsterdam, Among the members of the Soviet delegation are Melnichansky, Figat- ner, Yusopovitch and Tcherny, prom- inent Soviet trade union leaders. The Soviet delegation will make a de- claration at the conference explain- ing the attitude of the proletariat of the Soviet Union to the methods to be used in the struggle against war. Copyright, 1929, by Internatio: Publishers Co., Inc. BILL HAYWOOD’ BOOK TODAY: A Cowboy Feud at a Nevada Rode: a Duel—Weapons, Six-Shooter Against a Lariat; the Story of Walter Rice All rights reserved. Republica- tion forbidden except by permission. In foregoing chapters Haywood wrote of his boyhood among th Mormons at Salt Lake City, his birthplace; the rough life of the oi west in mining camps where he got his first schooling and met h first sweetheart; a miner at nine; odd jobs at Salt Lake City; his fir: strike; his years in a remote Nevada mine; converted to the caus of labor; marriage and a baby; mining again; homesteading harc ships; domestic distress with a sick wife. Now go on reading.—Edito * * PART XII. At THE fall rodeo of the cattle ranches of northern Nevada the: ‘were some bad men among the cowpunchers, quick on the trigg« and ready to shoot at the drop of a hat, some of the best broneh busters of the West and some who were experts with riatas. The outfit was camped for two nights on the left bank of the Humboldt River, a few miles from the lively town of Winnemucca, where the cowboys did much drinking, wild riding and reckless shooting, which was nothing out of the ordinary. This was the scene of a tragic fight between two cowboys, one armed with a double action six-shooter, the other with a viata, I'll give you the story as Walter Rice, one of the participants, told it to me when he came to McDermitt. I was crossing the parade ground one day when I saw a vaquero coming down the road, easily discernible from the way he rode, and from his outfit. I wore chapereros, the leg guards of the cowboys, made of goatskin wi long hair outside, a sombrero was set on the back of his head, ar long tapaderos flapped in unison with the nodding head of his big fin looking cream colored horse. Before I recognized him he called out: “Hello, Bill!” Touching his horse with the spurs he rode up on a jump, pullir his mount back on its haunches just as he reached me. He put o his hand with a western “How?” “Good,” I said, “get down and look at your saddle. Put up yor horse and have a bite.” We started back toward the barn. * * “I don’t know whether I’m going to stay long. I’ve got a story tell you.” Pulling out the makings, he rolled a cigarette. “All right,” I said, “but wait till after dinner. I guess you’ hungry.” “Hungry is no name for it. I crossed the Diamond-A desert ye terday without a stop, and rode from the other side of Buckskin Mou™ tain this morning.” Knowing the distance, I looked at him and remarked: “You must have been in a big hurry.” “Yes, Yet I don’t know but what I’m going the wrong way. haven’t heard anything?” “Not a thing. But let’s eat. Then you can tell your beads.” After dinner we went out and sat on the grass. Rice said: “I think I killed a man before I left camp.” Surprised, I asked how, “Give me a match. I'll tell you just how it happened,” he sa after wetting with his tongue the cigarette he had been rolling. was riding for the P-bench ranch with the rodeo. We camped j: north of Stauffer’s field on the Humboldt, and had the saddle hors in the field. The first night some of the boys come back from tov pretty drunk, I had rolled my bed next to Mex Ricardo. I didn’t p much attention to him, took off my gun and slipped it between t blankets under my coat that I had rolled up for a pillow. Next mor ing when I got up, I straightened the blankets a little, rolled them in the canvas, washed and went to breakfast. After breakfast I we back for my gun. I: was gone. None of the boys had seen any o around my bed. I didn’t think of Ricardo at the time. But I sure w mad. That gun was a beauty, pearl-handled, blue-barreled, thir eight on a forty-five frame. A kind of a keepsake that I hated lose. Where I got it is another story. * y * * “Nearly every one was saddled up before I caught a wall-e; pinto that I rode that day. We were moping along through the | | hills between the river and the Toll-house when Tom Baudoin, ridi just behind me, sung out, ‘Rice, I thought, you said you’d never 5 your gun?’ ‘What for would I want to sell it?’ I said; ‘I couldn’t b a better one.’ ‘Oh!’ he says, ‘I thought you sold it to Ricardo. Y just let him take it, huh?’ ‘No, I’m damned if I did,’ I told him, Td 1 to see that Mexican right now.’ “We got through early that afternoon. When we had parted « the beef steers and had done what little branding there was to do, ‘ sun was still high. | Everybody worked lively; guess they wanted get to town, for it ’ud be their last chance to clean up for quite a wh I met Ricardo at the chuck wagon and said to him, ‘What did you with my gun?’ He answered kind of sheepish-like, ‘I throwed it the river.’ I told him he’d have to be a damned good diver becaus: was going to make him get it. He was kind of playing me for a j belly, I guess. He said, ‘Don’t get sore; I'll give it back to you in « morning,’ and walked off with his plate and knife and fork. Pre soon I saw him cinching his saddle. I knew he was going to town. “He didn’t show off much that night before the senoritas. hhadn’t unsaddled Pinto yet. I went over and climbed on. My 1 was coiled loosely over the horn. I started after Mex, caught up w him, told him I wanted my gun and wanted it damn quick. I was expecting him to shoot. He had my gun inside the belt of his cha He pulled and plugged me through the arm here.” Pulling up his coat-sleeve, Rice showed me his left fore-a1 bandaged with a bloody handkerchief, and continued: “When he shot, his horse started to pitch, but Ricardo fired age just grazing my leg. That didn’t hurt much, but my arm did, I kn that I’d have to do something and do it quick. When his horse stop} bucking he’d get me sure. So I grabbed my riata, held the coils this arm but it couldn’t do much, swung my loop and tossed the str’ on him just as the bay colt he was riding quit jumping. I took turns and started for camp. He struck the ground with a thump. could feel that we were pulling up sage-brush, but I didn’t stop w we got to the wagon. “There was some excitement. One of the boys took my rope ‘ I coiled it up and asked the fellers who were looking at Mex if was dea’, They couldn’t tell. I said, guess I'll go for a doctor and this fixea up while I’m in town, My arm was bleeding a stream. ‘ me tie that up before you start,’ said one of the boys, taking his b danna off his neck. He tied it. tightly around my arm above wound. It didn’t take a minute. Guy Kendrick made the ride with m * s . In the next instalment Haywood tells of the end of the duel tween the two cowboys; how one of them had a sweetheart but o how she had another; killed with his own gun; Billy Beers the ranc and how he liked to eat; Haywood’s homestead hope collapses, a fe ful blow; dark days and Coxey’s army. At Lenin’s Tomb