The Daily Worker Newspaper, August 16, 1927, Page 6

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

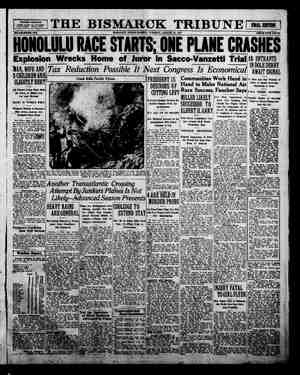

~Jater “The Camp” was opened, on June 19th. " opening on this day. “ necessity of participation in the co-operative movement Page ‘Six ‘ tne REE THE DAILY WORKER, NEW YORK, TUESDAY, AUGUST 16, 1927 Boston Capmakers Plan | Celebration Saturday of} Their 40-Hour Victory): By J. LOUIS ENGDAHL. HE ruling class professes to be very much troubled how the workers will spend their spare time when| the workday is shortened. Judge Elbert H. Gary. on Mon the steel trust head, who died | d as one of his arguments in “that it would keep the work- ore prohibition was supposed to have dried up the saloons, it was charged that the shorter would cause work to spend more time around workd : the grogshops. In fact, the fewer the hours of labor,| the worse for labor, in the eyes of the “open shop” ex- | ploiters. | , who feared that a shorter work- , helping in part to cripple the day of toil. Nevertheless, the movement has made progress. * * * is significant that this Saturday afternoon, the} progressives in the Capmakers’ Union, in Boston, are planning to play hosts to all the progressives in the needle trades in the metropolis of Fuller, Thayer and the other would-be murderers of Nicola Sacco and Bar- tolomeo Vanzetti, a 40-hour week celebration to be held at Camp Nitgedeiget, near Franklin, Mass. The Capn ’ Union this spring won the 40-hour week in B ‘The progressive capmakers believe that the 40-h be won by all the other work- jes, so they are trying to get them to talk it over and plan for this new advance on the industrial battlefield. Camp Nitgedeiget (Don’t Worry) is itself the best answer to the employers’ fraudulent dxead that the workers will not know what to do with their spare time. The “40-hour, five-day week means Saturday off, as well as Sunday. It means one more day in the open. Another day to recuperate from the ‘ravages of toil, that makes the worker victim of the many occupational dis- eases that hover like buzzards seeking their prey about every industry. Camp Nitgedeiget, perched on one of the highest spots in the entire state of Massachusetts, looking off over Lake Uncas, and giving an eye-resting view of far- away hills, is born out of conditions arising from two days’ rest in seven. \ ers in the ne together this * * * e Tt is 28 miles as the automobiles go, from the prison cells that hold Sacco and Vanzetti, to Camp Nitgedeiget. But there is a closer relation, because Sacco and Van- zetti sought to win some of the joys of recreation and education, that “The Camp” makes possible, for the less favored, the unorganized workers in the great New Eng- land industries of shoes and textiles. I felt this close relation as I journeyed from Boston to “The Camp” to become one of the speakers at last Sunday’s celebration of the progress that “The Camp” has made, Camp Nitgedeiget is the first effort of the United Workers’ Co-operative Association that was brought in- to being at a conference of 20 workers’ organizations held last Feb. 27, in Boston. Less than four months It now has more than 400 members drawn from the Workers (Communist) Party, many trade unions, the Workmen’s Circle and other similar organizations. There are 95 acres in all, with 27 acres of lake and the rest in open field and dense woods, strong scented with evergreens. * * During the summer many workers have come to Camp Nitgedeiget and given voluntarily of their labor, in t! construction of spacious and comfortable cottages, in the clearing away of timber, in the building of roads, in performing the multitudes of tasks that transform a wild place in the open into a comfortable place of recreation for thousands. It was estimated that 2,000 visited “The Camp” last Sunday, many to remain thruout the week. Meyer Birnbaum, chairman of the board of directors, presided at the day’s program, For the purpose of gatherings of this kind, a stage has been erected high on a rock, to be faced on one side by a natural amphi- theater. Israel Kutisker spoke on behalf of the Jewish Bureau of the Workers (Communist) Party; S. D. Levine, for The Freiheit; Sol Friedman, for Workman’s Circle, No. 718; Fanny Aissen, secretary, fer the Moth- ers’ League, while Sarah Fel Yelin, read the camp hymn, “Nitgedeiget,” that has been set to music by Harry Rosen, who is graduating out of “The Pioneers” into the Young Workers League. ‘ * * * * * I brought the greetings of the Workers (Communist) Party and of The DAILY WORKER. The message was warmly greeted, altho perhaps the majority of those in attendance were non-party members. But they were close sympathizers. The day’s attendance was consid- ered a triumph in view of the fact that the right wing- ers have established a camp of their own, and had ex- erted considerable effort to draw a large crowd to their It was not difficult to impress upon this audience the generally. They were convinced co-operators. Yet they were happy to hear of the role the co-oper- ative movement is playing in the reconstruction era in the Union of Soviet Republics, On the other hand, I Ten Days in the Workhouse By REBECCA GRECHT. PART II. FAIRLY large room with a smaller | one adjoining. A cement floor.| ral barred “windows, through | which on one side could be seen the} Hast Ri and on the other a wel-| come vision of grass and trees. And beds, beds, beds,—iron cots, one right | next to the other, with not even walk- | ing space between. This constituted | the quarters of the imprisoned fur pickets in the Workhouse for Women. | We were greeted with cries of joy| by a group of comrades who had been| given a 3-day sentence the day be-| fore, atid were already occupying the| room. They had been expecting us| since morning. Men prison under guard, had been setting up iron cots all day, for the additional guests. All Together. How glad we were to find pur- selves all together, instead of in separate cells. What mattered it that | our two rooms had twice as many in. mates as they should have had, even under prison rules, or that we had to| climb over other beds to get to our own? Were we not all comrades? That word seemed especially dear to us, then. | The situation was not so terrible, | after all. We could survive it. It} ‘was really entirely up to us—how we | reacted. And at the most, we’d be} confined only for ten days. Mili- | tants have- endured far more than| that, as penalty for their activity in | the battle against capitalist exploita- tion. These thoughts could be read on the faces of our comrades, as we examined our “property”—a bed, with three blankets, one as a covering and two in place of a matress; a small straw pillow; gome aluminum utensils for our food; a piece of soap; a hand towel to be shared by two or three comrades. A Queer Food. We did not have time or energy to investigate our surroundings more} closely. We-awere hungry, and our| only concern, for the moment, was to} get food. We ‘had arrived after the supper hour, but the matrons were| gracious enough to give us our intro- duction to prison fare that night.! Two slices of white bread, half-baked, with a strange, unpalatable flavor, aj} plate of spaghetti, evidently medica- ted, repulsive to look at and worse to eat, and. some muddy tea—that was supper. % | Shall we ever forget that tea? It) was the puzzle of the workhouse. Wel held a conference to decide what it| contained, how it could be described. | It might have been dish water, Pos- | sibly, in the far distant past, its chief ingredient may have resembled a tea leaf. The drop of milk it was sup- posed to contain may have once upon a time actually come from a cow. But opinions differed, and not being able to make a chemical analysis, we never came to any conclusion. Suffice it to say that none of us drank it, that first night. Nor did we eat the spaghetti. Then Darkness. At nine o'clock, the lights were | turned out. And much was forgotten, | no doubt, as we slept in utter weari- | ness, glad that one day was gone. | The next morning a few of us held} a consultation. Some comrades were! leaving that day. A few had received | a five-day sentence and would leave on Monday. The rest—83 in all, were | to serve 10 days or more. It was} evident that some sort of order had| to obtain, some system had_to be or- ganized. We had to establish a firm feeling of comradeship, or the dis-| comforts and irksomeness of prison! life might cause us, naturally enough, to vent our dissafisfaction upon one anothér. And we were determined to! keep up our spirit and courage. | Organization. We called all the comrades to- gether, spoke about the situation, and elected a committee of three, to- take charge of our little community. The first matter we took up was the question of food. The supper of the night before, the morning’s break- fast of a bit of cereal, watery milk, and sugarless coffee, had made us realize what a problem that would be. Comrades, we said, you must forget about all the good things you ate be- fore. Forget that you liked your mother’s cooking, or your own, or the restaurant meals you may be accus- tomed to. We must keep up our strength, and not weaken ourselves physically. Let us try to eat every- thing—as much as we can, | which “we all gladly joined. told. We asked them to speak to/ him. We sent him a note. We re-| quested an interview. We got no reply. His majesty, the warden of the workhouse, whose hobbies, we} were informed, were dinners and ban-| quets and card parties, and whose! table overflowed with all good things, including certain stimulating) and soothing delights, could make no ex-| ceptions for such lawless individuals | as strikers. This was prison, and we | were criminals. That settled the matter. We waited a week for dury fruit, and then—But of that later. Health Endangered. | We investigated our surroundings. | Our quarters were called the Annex. | Next to us was the Special Ward. | Tere were supposed to be first- timers, and those not suffering from any_veneral disease—street walkers, | keepers of houses of prostitution, | pickpockets, drunkards, young ones, | old ones, all together. Upstairs were | the drugeaddicts, the colored ward, | the medical ward. Outside, in the| “flats,” were single cells for diseased | prostitutes, etc. We were compelled | to use their toilet, to wash our dishes in the same room. . We learned much of what goes on there in the workhouse. We heard from those unfortunates stories to make one’s blood.run cold. Said one, a young girl, arrested for prostitu- tion, “The next time I come here, it will be for something real.” And another, with a sly grin, “What I’ve rned here, I never knew outside.” | id a third, hard-boiled, indifferent, | “They caught me again—this is the second time I’m here. The next time they'll have a harder time getting me.” And this is the House of Correction. In these surroundings, no, doubt, Judge Ewald thought we would be cured of our ‘criminal tendency to strike, to picket. On the contrary, it made us feel only the more keenly the injustice existing in the present system of society, the miserable fail- ure of millions of lives which capi- talism is respongible for. It made) us even more eager to fight to put an | end to the system of exploitation and | oppression that makes such condi- | tions possible. All of the regular inmates are given some work to do. And here before} proceeding further, let me make a} confession. I am sure it will be very | disappointing to all who read this; tale of our experiences in the work-| house; but cost what it may, the truth | must be told. No Work. Many comrades have asked me, Did they put you to work? Sue did you | all do? Perhaps it would be more} interesting to speak of chopping wood, or cutting stones, or peeling potatoes, scrubbing floors, and sew- ing prison uniforms. That would surely lend more of a glamour, an air of romance, to our experience. But alack and alas—we must admit the sorrowful, prosaic fact. We were not | put to work. Physical labor didn’t cause our muscles to ache at. the end | of ‘the day. We were ladies of | leisure, within the four walls of our prison room. \ Our chief tasks was sweeping and washing the floor, every morning, after breakfast. That, indeed, was a sight to gratify the most exacting | ousekeeper. Thirty girls, or more, busy pushing beds aside, carrying | pails of water, sweeping, mopping, | wringing—a real physical relief, in There was no other work to give us. In fact, we were a bit of a puzzle to the matrons, right from the start. They| had never dealt much with strikers before. They didn’t exactly know what to do with us. But we taught them,. before we left, what a political prisoner means. But Hard Beds. If our muscles didn’t ache from workhouse labor, they ached from other causes. To sleep on those hard cots, with only two thin blankets separating us from the hard spring, was quite a test of physical endur- ance. When we woke in the morn- ing, we felt every mark of the spring on our backs and sides. We offsét that, however. One of the first habits our little community established was exercise, before breakfast and after supper. For ten or fifteen minutes, twice daily, we jumped, kicked, bent, twisted, turned our heads and arms and legs —all in a narrow space between two rows of cots. The stout ones among us began to lose excess weight (or! so they hoped), round shoulders be- | The Blood of Martyrs |fat paw! | sky. jof meat and pitch, of oil and coal and cotton and leather | | brothers to death. For not willing to make peace with By M. J. OLGIN. Translated from the Freihéit by Joseph N. Katz. HEY are spilling our blood. They squeeze it out with iron presses in the iron factories; they let it, drip—pitch-black streamlets—in coal catacombs; they suck’it into delicate silks, expen- sive points, caressing furs, beauty, splendor. They stand over our heads with a whip woven of hunger, fear, desperation. They pelt our bodies with thorns of shame, contempt and hatred. They stand up a golden mummy among us and say: “Bow! Kiss the Burn incense for. the wide-opened mouth!” When we say “No,” they call the executioners. Adorned with things showy are the executioners. Vel- vety-soft the clean hands. Clear oil the round words. Pious the mien, holy the sigh. “In the name of Justice. In the name of Equality. in the name of God almighty, we put you down on the block, and for your own good, in order that you should no more be able to sin, we cut assunder for your rebellious neck. Amen. Amen.” In the name of Right. In the name of Democracy. * WIND blows. A quiet evening falls down upon fruit- laden fields. Rivulets murmur. ‘Somewhere sings a grill. Somewhere smells a rose. Above lies a wide blue In their death-house wait two comrades. In their grave-house count two comrade the remaining minutes. One turns for the last time with death-scorched lips to the brother workers of the whole world. One weaves yet from gall and irony an unfinished curse. A large, bony hand reaches out, grips them around, chokes, chokes. ... In large libraries, among old, heavy bands, with clean mind and quiet héart, sit the learned executioners. Beau- tiful is the world. God is just. Godly is the sentence. The will of the rulers be done. Hey, you, overworked, famished, wake up! You, iron-smelters' of Gary, lift up your eyes from the inferno, wipe the sweat from the burned brows, look about! / You, copper-diggers from Montana, straighten out * * your bent spines, let down your heavy axes, which drill | © the belly of the earth, listen! You, gum-spillers of Aikron, turn away your faces from the hot, bad-smelling stuffs, catch the pain-racked breath, ask: what’s happening? You, weavers of Lawrence, stop the devilish-hastening machines, go out of the overheated torture chambers, talk things over! Pe You, railway-machinists over the length and breadth of the mighty land. Catch the news, that carries itself from near and far,’ conclude, understand its meaning; You, workers of steel and wood, of linen and stone, and gold and tin, you who Work upon the ground and | under the water and in the woods and over the houses and in the bellies of the heavy-laden ships, who build the mighty land—from the age-old Canadian woods to} the blue Caribbean waters, from the eternally feverish | New York to the dreamy, flower-woven San Diego and| far over the shores of Mexico and further—you all tor- tured, driven, never with bread sure, with feet stepped | upon, by no man respected—look about what. is (done) with you. For a word of restlessness they send your your slavery they slaughter these fighters. Insolent, haughty, brutal, before all your eyes they lead upon the echafot the storm-birds of your class, theecallers of your emancipation? t Hey, you, slaves, when will you already feel, that you are the strong and that no strength can stand against you, if you only will? * 4 'ACCO! VANZETTI! Brother martyrs! Like the first | birds of Spring you hit against the ice of‘ your broth- ers’ hearts, the ice of ignorance, dullness, indifference. You have drop by drop given away the warm blood of your love-full hearts and the ice is beginning to melt. Sacco! Vanzetti! In a dark time you were brought to the edge of the grave, in an hour of history when the whip whistles, the wolves howl and the appetite grows —and loosely hang the hands of the masses and you have been betrayed by the leaders, and the yellow god of plunder and shame grinds his teeth and laughs at the | world. Sacco! Vanzetti! We have done and do all, that we can—we the few, the seeing, the forward-going, the un- defeated. We have surroufided you with our love, as with a red fortress; we have fanned you with the storm of our protests; we have lifted up our voices in a high and burning cry. But small is our number among the tens of millions of our class-brothers, who still lie caught in the foe’s nets, and great is the betrayal of those, who could, but did not want to drill through the deaf wall and uplift the masses. ’ But you must live! * * * ROTHERS! Martyrs! Great is the pain., Heavy the heart. Why should we deny it—it is a day of! mourning for us all. Sacco! Vanzetti! Take heart: you are not alone. are with you. Our heart is filled with your pain. blood trembles with every drop of your blood. Sacco! Vanzetti! We swear. By your martyrdom do we swear to hold fast the flag, to go daringly forward, to awaken the fallen away, to unite the divided, to make | seeing the blind, to forge a strength, to lift a fist. | Sacco! Vanzetti! Not for nothing is your sacrifice. | Upon good ground fall the seeds of your work. There will come a day. The slave will arise. A brother will recognize a brother. The ranks will close. Revenge will come. Freedom will come. . From martyr-blood will arise liberation. We Our First pictures of some of the originating in the Dead Sea-regi 400 lives: Top, one of the deep the heavy tremors. palace at Jericho, In this building, three Indian tourists were killed and buried. results of earthquake in Palestine, ion, causing the loss of more thae fissures at the Dead Sea caused by Below, ruins of the newly constructed winter Katie, a Miner’s Child By VERA BUCH. Katie Vratrick, six years old, is the | daughter of an anthracite coal miner. She is little, thin, and quick, with gray eyes dancing in her thin little face that has such a roquish smile. Her parents come from Jugo-Slavia, in southern Europe, but she, Katie, was born in great, noble, free America. So great that it lets Katie and her brothers grow up in a bare, ugly little shack, bitter cold in winter. So noble, that it allows her father to work deep down inside the earth, in the dark, dangerous mine, where more workers are killed every year by accident than in any other country in the world. So free, that when the boss finds out from his spies that Katie’s father be- longs to the Workers’ Party, he is at once fired from his job and often, be- fore he can find another, is out of work a long time, and then there is not enough to eat. in the house. In summer, Katie runs with the other children on the coal heaps. There she is perfectly happy, bare- footed, in a torn dress. She ;comes home at night black#as a coal miner, and must get scrubbed with soap be-| fore she can go to bed. High as the mountains are the coal heaps, the} playground of, the miners’ children. They belong to the colliery which is only a few doors from Katie’s home. Sometimes Katie manages to slip in- to “the breakers, that great, black, noisy building, towering into the sky, where: the coal is crushed, Here she stands wide-eyed and silent amid the din, watching the rushing streams of black, shining coal. So near is the colliery to their home, that day and night they can hear its loud noises, like the roaring of the sea, Only Katie at night, hears nothing, she| falls asleep the minute she tumbles down on the feather tick on the floor where she sleeps with her three brothers. Some days, she goes with her mother, carrying a pail, to help pick coal. That js a hard job for her mother, Katie knows, and gives her a backache. Last winter her mother ee to have an operation because of | doing too much heavy work. Since ‘then Katie tries to help her with the | dish-washing and cooking for their |family of six and four boarders. | If winter, she goes to the hateful school where she must sing a thou- ‘sand times: “I pledge allegiance to | my flag,” and “My country tis of thee.” At honte. she learns very different things. Her mother taught ‘her the “International.” The tune she can’t get right, but she sings it with her own tune. “Arise, ye wretched of the earth!” Katie knows who are the “wretched of the earth.” They are the coal miners, like her father, bent and broken from the hard work in the mines; like her mother’ who has always a backache ; from washing and cleaning 4nd must | Worry so much how to get clothes | for the children and pay the ‘rent; like herself, who feels so keenly all the dark,’terrible things that weigh upon their life. Katie tells, you: “I~went to Pas- | saic.” If you are clever you will say: “You mean, you saw the Passaic Strike movie.” Then she’ll nod her head vigorously. “I saw the picket | line, and the cops, and Brother Weis- | bord speaking to the workers,” She can’t remember the last miners’ strike, she was too little, but her mother will tell you how she used to run out on the porch and yell “cab, ’cab,” when the scabs would pass by towards the colliery. Now she'll tell you: “Boss—chop his head off—hate him!” Her brothers have organized a Pioneer club in- the little village. Katie is too young now to join, but she comes to the meetings and listens with wide eyes to what the leader says. She is waiting to be old enough | to join so that she can show what a good fighter she, too, can be for the | working class. TEN DAYS IN THE WORK- HOUSE (Continued from 8rd Column). a week, in the prison yard. | All day long we were confined indoors. And ‘the glimpse we had through the win- dows of the river, and the fresh grass and blue sky, only made our confine- | ment worse, Besides, for us to be! pay your fine. You can go home.” | We said not a word, and waited quietly. The comrade at first hesi- | tatingly said no, but when told that her mother was ill, she chan; her mind. In a few minutes she was gone. One of our comrades had weakened. » It hurt us, saddened us, ineveased the air of depression whicd pressed like a heavy wall against us. But we gaid little. suddenly deprived of activity, while. |our comrades outside were working | and struggling, meant a strain that) SEND IN YOUR LETTERS | pointed out that under Mussolini, in Italy, the co-oper- ative movement, as well as the trade unions and the party, had been outlawed by fascism. * * * gan to straighten out, chests ex-| We swear. panded. In the beginning only 10 or} 12 joined in. Later, there were more | than 20. The matrons stopped to) And try we did. Gradually the} food line lehgthened, when meal time | came around. The beans, the watery | soup, the mashed potatoes—all very | A few minutes later, the matron came in again, and called out three more names. No reply. “Your rela- _ tives are here to take you out. Don’t : we could not deny. | The ruling cl: fedrs the bona fide co-operative movement of the working class, and already Camp Nitgedeiget has been raided by the bloodhounds of the Thayer-Fuller plunderbund, hunting for evidence with which to discredit labor's militants, especially in the needle trades unions. ‘ ee. | * Tt was across one of the long tables of the huge dining room that I again met William Seligman, chairman of Capmakers’ Local Union No. 7, who had spent last Tuesday in company with Jacob Miller, president of the union, in the custody of the police. Seligman and Miller had been charged in the press with being implicated in the bomb b in New York City. The police had fol- lowed what then considered a “hot trail” to “The Camp,” where Miller and Seligman had spent the previoug Sun- day. It is declared they found two sticks of dynamite, | explosives used in blasting stumps and building Toads. | * * * * | Suffice it to say that every capitalist sheet in Boston | had to go down on its knees and apologize thru its col- umns for the lies that had been spread. Thus we fi on the first page of The Boston Post, for instance, Fri-| day, August 12, this headline: - "NO KNOWLEDGE OF BOMB PLOT; YOUNG MEN ABSOLVED OF ANY CONNECTION.” Then for more than a quarter of a column “The Bost” | points out that the police officials had satisfied them- (Continued on 4th Column). highly seasoned with pepper to ob-| literate the taste of what had been} put in; the bit of meat, sometimes sickeningly sweet, sometimes hard as wood, the dry bread and spaghetti—all | of this we learned to eat. Some even began to drink the “tea,” welcome} after a constant diet of starch. But} a few, up to the last, ate nothing but | bread, a boiled potato, and a little | milk. Headaches, stomach aches— these were daily occurrences. But our decision proved to be much better than a policy of fasting. High Living Warden. One privation, however, we felt keenly. No food can be sent in from, the outside, but once a week the | prisoners of the workhouse may buy fruit and crackers. On Sundays they fill out commissary slips, and on Thursdays they receive their orders.}| We arrived late Thursday afternoon. We had just missed commissary. We spoke to the matrons, asking whether an exception could he made in our case, as otherwise we would have to! subsist on prison food only for a full week. And our girls might become ill.\, It is up to the warden, we were * i | watch in amazement. Exercise of that sort had never heen seen, ap- parently, in the workhouse. But a: for us, we enjoyed it. It helped the days pass more quickly and it brought us more closely together. First Experience. But let it not be thought that we were merely spending our vacation in the workhouse. Or that we were unfailingly optimistic and in good spirits. We were in prison, and we felt it. In the long run, ten days are nothing—-a meré™smoment in a life- time. And in comparison with the years of suffering to which class war prisoners in America and in other countries have been and are sub- jected, our terms was a_ trifling matter. But most of us had never spent even a day in jail. This was our first experience. There were moments when we were overwhelmed with loneliness, and im- patience, and sadness. We were not. permitted to get newspapers or other reading matter. We could not leave the building, get out into ‘the fresh air. That is permitted only once in (Continued on 5th Column). | The DAILY WORKER is anxious to réceive letters |from its readers st4ting their views on the issues con- |fronting the labor movement. It is our hope to de- | | velop a “Letter Box” department that will be, of wide | interest to all members of The DAILY WORKER family. | Send in your letter today to “The Letter Box,” The | | DAILY WORKER, 33 First street, New York City. | CELEBRATE FORTY-HOUR VICTOR Xe (Continued from 1st Column). | -selves that “the men were innocent of any connection | with a plot.” But in the meantime the lies had been spread over the nation, ¥ * * So we could forget about “the plot,” for the time be- ing, and discuss the 10-hour week celebration that the progressive needle trades workers will celebrate at Camp Nitgedeiget this Saturday. “The Camp” breathes the struggle of labor; the struggle that the exploiters fear. Incidentally an important section of “The Camp” has been set aside and is fully occupied by “The Pioneers.” Even the youthful reserves of the working class, thru | education as well as recreation, are ig efforts of Inbor ahead. being trained for the ;complaint of another. Keeping a Brave Front. But, howver, miserable we may have felt at one time or another, we tried not to speak of it openly, so as not to! affect the others. “I feel so impa-) tient, that I could just scream,” says | ome comrade softly. “Sream inside, to yourself,” is the answer. “How de- pressed I feel. It’s so hard to sleep. There isn’t enough air,” is the quiet “Tam. so} anxious to learn what is happening | on the picket line, how the strike is progressing, that I cannot rest,” says a third, in a whisper. But aloud we laugh and joke and sing. It is part of the battle—a mere pastime. It will soer pass. And our feeling of comradeship grows, our solidarity re- mains. We had a test of that, on Saturday, the third day of our imprisonment. It was long_after supper, almost 8 o'clock. We were very quiet, that evening. The gloom of the work- house seemed to have enveloped us. On the faces of many comrades could be seen an expression of utter weari- you want to go home?” “We're not going!” was the determined response. Again the matron left, and again she returned, this time with a special message for Comrade Steinberg, one of the three, that her daughter had collapsed. We looked at the coms yade. ‘There was eager questioning. in ous eyes. We felt that the states ment of illness in the family, as in the case of the other comrade, was simply 2 ruse. But would\this comrade stick, or would she go? And when Com- rade Steinberg gave her final, em phatie. Nol, it? was if a current of fresh air had suddenly been blown into.the room. It made us happy in- deed, relieved our tenseness, dispelled —- the gloom. é The matron may have thought us queer lot—but we felt proud of our comrade, » And when the next day we sang our songs of ah ok was with added enthusiasm and spirit. We were going to stick through to the end, the rest | holy. Sudd the is and called a 4] as militant fighters sh