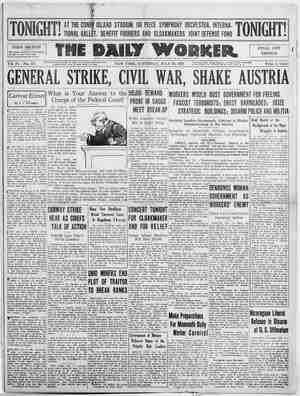

The Daily Worker Newspaper, July 16, 1927, Page 9

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Housing in the Soviet Union ene visiting the U. S. S. R. are in- variably surprised at the changes which have taken place within the last few years in the country which they formerly knew as Russia. They are accustomed to think of Russia as an ignorant, barbaric country. This they learned from books on old pre-revolutionary Russia. During the war with Germany I lived with an Austrian prisoner of war. He was an excellent locksmith and the Russian officials forced him, therefore, to work in a munition factory. He re- ceived very little wages as he was an “enemy.” What always surprised me was how that man could live in a cultured and clean manner on his meagre earn- ings. He bought neck-ties and white shirts. After work he used to wash and dress up and take a walk out of town. Later on he made me teach him Rus- sian and he read the daily press. That surprised me at that time, and it surprised many others, We used to say, “here is a cultured man.” Twelve years have elapsed since then. Not so long ago (only a month ago, I lived in Ivanovo-Voznes- sensk) I travelled’ again through the oil districts of Baku and Grozny. I often thought of my Aus- trian friend. If I knew where he was I should write him a cheerful letter saying: “Friend, we have caught up with you, in fact, we will soon be ahead of you. At any rate you would not surprise me any more with your neck- ties, white shirts and cultured manners.” eee Heusing In Czarist Days. es It is very interesting to observe how our working man changes. He is not to be recognized. Here is an oil pumper, a Persian from the Baku oil fields. Pumping oil is tedious and monotonous work. The Persian is ignorant; he has a poor knowl- edge of the Russian language. He recently left his native country as he was threatened with death from starvation. The only aim in life of that Musselman is to have enough to eat, The “enlightened” bourgeoisie says about such people: “He is despicable; he is just like an animal.” Perhaps in their eyes he does resemble a beast; for them every man should possess a dinner jacket. The eyes of a Russian proletarian are somewhat different. An ignorant, filthy, ragged man is a brother at work and a class relative. When the mil- lionaire bosses had charge of him, he lived under horrible conditions, his domicile could not even be compared with a stable. One must know the dark, low, stuffy, over-crowded barracks in the oil-dis- tricts to realize the significance of house construc- tion for the Russian workers. The Persian knew his filthy corner in the barrack. To this corner he brought his wife, there she bore him his children; there he lay ill in filth and dark- ness. He knew no other life. He could not imagine anything better. He saty the large European Baku with the masters’ palaces, their fast trotting horses and automobiles, but that was all for them; for him these were things beyond reach. And suddenly the Persian is given an apartment. Ye is no longer in a corner, no longer in filth; he 1as a light apartment—three whitewashed rooms. He is bewildered. He, the down-trodden, ignorant, Persian is ready to ery. In his apartment there is 1 gas-stove, a bath with hot water. He comes home from his work, washes, eats hot food, and every- where around him is light and cleanliness. What should he do now? Somehow he must arrange his life differently. He must now spend his after-work- ing hours differently. And here we see a man be- coming transformed. He is cleaner, he has bought himself a neck-tie and a shirt. He goes to the club; he is learning to read; the Persian is becom- ing a cultured worker. That is the essence of home construction in the U.S. S. R. That is its enormous significance. I saw hundreds of such houses in Baku scattered in small towns near the oil fields. Architecttrally they are . beautiful. They are light and comfortable. There By NIK. POGODIN (Baku) is the village and the club, flower-beds and electric railways which take one to work. The local admin- istration took it upon itself to build houses for the workers. It spent more than was allotted for hous- ing and the centre raised objections, but when peo- ple from Moscow came around and saw the differ- ence between the old horrible barracks and the new villages, they said smilingly: “Fine!” This is also the case in Grozny. The Grozny works can truly be called Soviet works as everything was burned down by the bandits during the civil war. Now the poweiful works have been restored, and they are known on the world market for the ben- zine they produce. Railways have been constructed. New villages are being built which resemble the small towns of Switzerland. Windows glisten in the sunshine, woman and children promenade the cheer- ful, sunny streets. Here is the local Ivanovo-Voznessensk Soviet. We are taken out to see a new workers’ town. It is built on European lines; the streets are cut straight, rows of trees are planted. In about two years the town will be like a garden. Further, we went from Orekhovo-Zuevo back to Donbas, the mining dis- trict, and the Urals, the metallurgical district. Everywhere new, light, workers’ towns are in con- struction and a new cultured Soviet worker is de- veloping. Ideas are determined by environment. ‘Light and rest which give a good home to the worker bring forth new desires for knowledge and for a rational, cultured, organized life. ~ *T=using Under the Soviets. July Days in Russia Ten Years Ago - (Continued from Page One) opportunists, arranged a demonstration of their own. But the masses, coming more and more under the influence of the Bolsheviks, changed it into a triumphal demand for the Bolshevik slogans against the coalition: All Power to the Soviets! With the Capitalist Ministers! Political Offensive? Down Down with the This was an attempt to force the moderates in the Soviets to act against the coalition government. But on the next day, after careful preparations, a counter-demonstration of the bourgeoisie took place. In order to stem the rising tide of discontent with and fury against the coalition the bourgeois (constitutional democratic) ministers resigned from the government. This act was a public admission of the instability of the coalition and convinced the revolutionary workers of Petrograd and the seeth- ing masses in the rest of the country that their de- mands were proper. It was apparent.that a great spontaneous movement was about to break in Petro- grad. The situation was tense. One false move might jeopardize the whole revolution. Kerensky, foreign minister in the coalition government, was now made premier while still retaining his port- folio as foreign minister. He and Tseretelli began frantic preparations to deliver the revolution into the hands of capitalism. He was waiting for time to mobilize the “loyal” regiments against the masses. The Bolsheviks, along with every other working class group, advised against demonstrations, did everything within their power to persuade the work- ers of Petrograd that such outbreaks would be futile. The leaders of the revolutionary proletariat were aware of the fact that the masses outside Petrograd, although profoundly affected by the events of the preceding months, were not ready for the decisive struggle. But the masses poured into the streets anyway. When the ‘July action took place and the masses were in the streets and face to face with the enemy it was no longer a question of debating. It was the imperative duty of the Bolshevik party to try to take the lead and impart a more peaceful character to the demonstrations and to give organized expression to their demands. The question of armed uprising could not yet be placed on the order of the day. The July days constituted the turning point of the revolution. The Social-Revolutionaries (who afterwards became paid agents of the Allied mili- tary missions in an attempt to overthrow the vic- GENEVA The powers round a table sit And play with loaded dice. A pistol’s hidden in each mit— And yet they smile so nice. They sit upon their mighty seats And talk of guns and speed, Of ratios and merchant fleets * And such like things, I read. They play for mastery of the sea And speak with bloated lips. They give no thought to you and me— We build and man their ships. Then let us say: “Kind sirs, attend! This game has gone too far. To all your navies make an end— We'll have no more of war!” HENRY REICH, JR. torious workers’ and peasants’ government) and Mensheviks exposed their true role as would-be hangmen of the revolution. They completely iden- tified themselves with the Cadets and other bour- geois reactionaries and aided the massacres of the Bolsheviks, the suppression of the Pravda, the ar- ~ “* rest of Trotsky, orders for the arrests of Lenin and Zinoviev, who were forced to flee for their lives, only to return on the wave of the November revo- lution. In assailing the Bolsheviks the members of the government put into circulation the most infamous slanders, repeating and elaborating the -fabrications to the effect that Lenin was a German agent in an effort to arouse, as they boasted, “the Savagery of the troops.” During the frightful reaction that set in the Kerensky government was eclipsed by the general staff of the army which was officered by junkers and agents of the allies. The Soviets likewise, with the exception of the Petrograd Soviet disappeared from the scene. The reaction proceeded with the disarming of the revolutionary regiments that had refused to participate in the pogroms against the workers who turned into the streets to vent their fury against the betrayers of the revolution. July Days in Russia clarified the party lines; no longer was there any doubt regarding the role of the Mensheviks as lackeys of the reaction and ene- mies of the proletariat. Kerensky tried ta divert the lightning-flashes of revolution by constantly promising to call for elections for the censtituent assembly, only to continuously postpon@ it. The Bolsheviks kept before the masses the slogan “All Power, to the Soviets,” as a rallying ety for the masses in an effort to overcome the effects of the counter-revolution, and assure the revival and the final triumph of the revolution, which was realized in a few short months.