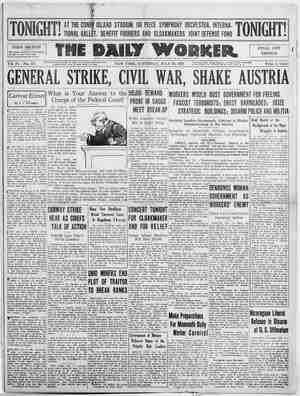

The Daily Worker Newspaper, July 16, 1927, Page 10

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Canton is also the head- quarters of the Canton Fed- eration. of Peasants’ Unions. This organization was in the early part of 1926 more or less confined to the prov- inces of Kwangtung and Kwangsi, but its influence was extending to other prov- inces. The organization of the Peasants’ Unions is as fol- lows: The’ peasants and small farmers in a village are organized in one unit. These units are grouped ia towns, districts and prov- inces. If more than one-third of the farmers join the union, then they form a branch. In small villages where there are less than 30 members, they cooperate with an adjoining village. Larger areas are sometimes divided into arrondissements. Mr. Wang, secretary and member of the execu- tive of the Federation of Peasant’s Unions, in- formed me that there are 66 districts comprising 60,000 members. The villagers hold mass meetings, the larger organizations delegate meetings. On the central executive committee there are 13 members. There is also a standing committee of five and in the districts standing committees -of three. Pro- vincia! congresses are held annually, district con- gresses every six. months, congresses in sections smaller than districts every three months and vil- lage meetings every month. Members of the central executive committee hold office for one year, of- ficials of distriet committees for six months and others for three months. The conditions for membership are as follows: Members 1.—Must own less than 100 mow of land (roughly less than 17 acres of land). 2.-—-Must not be farmers whose interests..conflict with the peasants. : 3.—Must not be moneylenders who mortgage farms. 4.—Must not be “churchmen.” 5.—Must not have connections with imperialists. The entrance fee is $1 {I was told sometimes less), There is 2 maximum monthly fee of 10 cents. Those who smoke opium or gamble are excluded. I asked Mr. Wang, the secretary, how they could know this. He replied that it was easily known to the village circle if, for instance, anyone was an habit- ual gambler. Persons who Ga szt attend three meetings ar those who refuse te ~-y the orders of ‘the party, are expelled. The chief points in the program of the Peasants’ Union are: 1.—To obtain better conditions for the peasants and small farmers. 2.—To improve village organizations, which are now in the hands of the landlords. 3.—To raise the social status of the peasants and small farmers. The farmers in Ewangtung, the province in which Canton is situated, are divided in two: those who are independent and those who are tenants of the landlords. Their condition is very bad on account of the bandits who infest the territory and also as a result of the fighting. The organizers of the Peasants’ Union stated, as regards the economic status of the peasants and small farmers, that the average size of the small farm belonging to an independent farmer was from 2 to 8 mow (one-third to one and one-third acres). One mow is said to produce about $30 per annum, so that the independent peasant farmer may get between $60 and $240, that is between £6 and £24 from his farm per year, The rent of these small farms often swallows up as much as one-half to two-thirds of the revenue. Not very long ago the provincial office of the peasant organizations had just two old tables cov- ered with papers in disorder, some rickety chairs, a poor desk and a poorly paid copyist who, having too much to do, could finish nothing, When I visited the headquarters of the Peasants’ Union in May 1926, there were five departments working regularly, organization, propaganda, economic and military de- A Chinese Peasant Hut. partments and the secretariat. Besides voluntary workers, there are twelve paid clerks. Four booklets and forty-three pictorial bulletins and slogans have been’ published. A weekly paper, the “Plough” ap- pears regularly in twenty to thirty sheets and 10,- 000 copies are distributed. The Peasants’ Organization has undoubtedly been of considerable military value to the Cantonese in assisting their advance in their Northern Expedition. ORGANIZATION OF WOMEN. The organization of women workers is one of the most pressing of China’s industrial problems. Wo- men and children are now more and more entering industry, in order to supplement the insufficient earnings of the father of the family; and the fact that in general they receive even lower wages helps to depress the rates of the men workers. At present, where they are organized at all, they appear to be organized with the men workers—and that is chiefly in the textile industry in Shanghai. True, in Canton, I was told of a trade union which had been in existence for two monts which organ- ized the women in a match factory together with the men; and of a women’s union in a stocking fac- tory, claiming 200 members, which is said to have been in existence for three years. But these are tiny numbers compared with the women employed in the cotton mills and silk filatures. In Shanghai, there are said to be 125,000 workers employed in textile factories, of whom 57,700 were stated to be organized in the cotton unions affiliated to the Shanghai Federation of Labor Unions. As more than 60 per cent of these cotton workers were said to be women, it is to be presumed that some of the organized workers are women, but TI could not ob- tain any specific figures. Probably, also, some of the women employed by the Chinese-owned Nanyang Bros. Tobaceo Co. are among those who are organized in Yellow unions in Shanghai, as about 70 per cent of the 5,000 work- ers employed by this company in Shanghai are apparently women. : In Shanghai the secretaries of both the Red and Yellow Union Federations stated that there was no organization at all among the silk workers, of whom there are 75,000, mostly women and girls. I was told that at one time a trade union was organized in the silk filatures by a Chinese woman worker. She was soon taken over by the Chinese employers ~ Organizing the Chinese Workers as a sort of welfare worker. All trade disputes went through her hands and in the opinion of the workers she looked after the employers’ interests and not theirs. She became an official safety-valve instead of a workers’ organiz*r—a much safer per- son. When I met her she appeared to be in very prosperous circumstances. Her volte face had rather disheartened the silk workers in Shanghai and dis- couraged any further attempts at organization. There were, however. in June 1926, a number of strikes, ane of them affecting as many as 30 silk filatures, in which 13,400 workers were involved, which indicate considerable solidarity among the women workers. Two of the strikes, according to the reports which I have seen, complained of the formation of a new Silk Filature Workers’ Union, charged the union with being in conspiracy with the owners to @elay the payment of the workers’ wages and demandél the closing down of the union; which was done hy order of the chief of the Woo- sung and Shanghai Constabulary. All this is dif- ficult to understand unless the new union was held by the workers to be a bogus organization set up by the employers, in order to forestall any other movement, Quite recently in Shanghai some women social workers have gone to reside in the chief silk filature area, in order to get into touch with the wemen workers, study their needs and help them to improve their conditions. The majority of the silk filature workers in China appear to be employed in the neighborhood of Can- ton. I was told that out of the 300,000 silk workers in factories in the whole country there were 200,000 workers, almost entirely women and children, em- ployed in 170 silk filatures at Shundak, about four hours by boat from Canton up the Pearl River. They have no organization at all, although their conditions of work appear to be just as bad as else- where in China. I asked the secretary of the All China Labor Fed- eration at Canton why no attempt is made to or- ganize the women in the silk filatures both at Can- ton and Shanghai—especially at Canton where trade unionism is legalized. He replied that 95 per cent. of the silk workers were women and therefore very difficult to organize. He also said that the bad con- ditions were partly due to Japanese competition and partly to the failure of the silkworms in the last two years. Such organization of women as is done appears to be largely on political lines. In the province of Kwangtung, where Canton is situated, considerable efforts have been made in this direction during the past year or more, There are three bodies, the Wo- men’s Freedom League, the League of Women’s Rights and the Organization of Women Revolution- aries. I discussed these with a Chinese woman who was working in the office of the: Women’s Freedom League, who spoke to me in French. I give the English equivalents of the titles as-best I can. (Continued en Page 7) KARL RADEK head of the Sun Yat Sen University in Moscow. —A friendly caricature by a Russian Artist. The Stevedore When ships come in from Glasgow, Singapore Or Java, stevedores have their work to do Unloading kapok, spices, wool or glue, Or from the Straits a cargo of tin ore, Or Madagasgar rubber’s to the fore, Or then again it’s cotton from Peru, Or burlap from Calcutta or a slew Of hides from Argentine to get ashore. And then come precious silks from far Japan And gold from Africa to please the plutes. — § — And though such cargoes nearly break a man I think of those who toil—mere beaten brutes— Beyond the seas producing all these things ° To swell the coffers of their lords and kings! —HENRY REICH, JR. a0. i A la I ca UNCC Pt HS