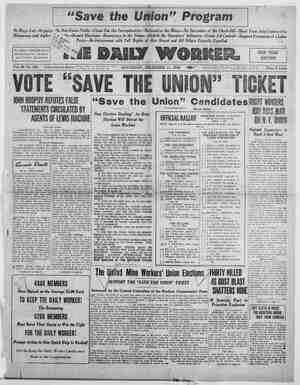

The Daily Worker Newspaper, December 11, 1926, Page 9

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

AG: Hes See a SS tT _ He Had Joined the Navy - - T was on one of my scouting expeditions, when I go out to examine what is variously called the hobo, the unemployed, the down-and-outer, or more pleasingly, the poor whom we have always with us. On these trips I almost invariably find someone in- teresting. This night I had a special hunch that I was going to run across something worth whole. I knew it for sure as soon ag I set eyes on him. He was a youth sitting on-a wooden bench which -van along the wall of a cheap poolroom in the West Madison Street district. He sat by himself and looked alien to his surroundings. I knew at a glance that he was not habitually accustomed to such a district. I knew that he was not one of the petty ‘larceny thieves who infest these pool halls. And, altho I am_no particular judge of racial character- istics, I knew immediately too that he was of North Italian stock, Now I have no racial prejudices or national fa- vorites on which to bet my money. But I will say this. Taking youth as a whole, by and large, I be- Neve there is no better class of young chaps than the boys of North Italian descent. If I were an ex- ploiter of labor, I would pick them as my victims every time. Besides being intelligent, well-manner- ed, courteous, and gentle of speech, they would give any establishment much the appearance of a male beauty show. : So I went and sat down by this youth, to get his story. I soon had it. Speaking both languages equally well, he had as a mere boy, in fact under the legal age, enlisted in the Italian navy, altho he had been born in this country. After serving there, he had enlisted in the United StateS~navy. Three weeks before I met him, he had been discharged in Boston, and given a ticket to Chicago as the place where he had enlisted. 2 Arriving here, he had no place to which to go. His parents were dead and his nearest relative in the city was an uncle with whom he was not on the best of terms. For three weeks he had been hunting for work, knowing no trade at which he could offer himself. His money had run out. For three nights he had slept out of doors, altho it was in April, and still cold. The night before he had slept in a contractor’s empty tool box on the street. Knowing that he was of course hungry, I took him to a restaurant. To my many readers on the Gold Coast, I will explain that, when you take a chap of that character into an eating place, you have difficulty in getting rid of your money. They will sit down to the lunch counter and remark casually that they believe they will have a sandwich and a ~eup of coffee. You. heve to urge them to order some- thing that looks like a meal, Even then they will pass over the steaks and chops on the card and light on hamburger or liver and bacon, as being cheap. And they never have room for any dessert. They fear to impose on your generosity. I did get some- thing like a meal down DeRose, for that was his name, but he refused dessert. After we were safely in the restaurant and he could not thereby be suspected of hinting for a meal, he mentioned that he had not eaten for twenty-four hours. Said he positively could not go out on the street and ask men for money. He said that about a half hour before I appeared on the horizon, he had decided that he must do so. He had gone out, met a man who looked kind, stopped him, and then at the last moment his courage had failed him ahd he had asked for a match. Taking his match, with no cigarettes to be lighted with it, he had gone back and again sat down on the pool hall bench, where - I had found him. Later in the evening he admit- ted that he had not eaten as much at my expense as he really wished—because he did not care to spend my money. For that he got a mild bawling out. I bought him a bed. As I was about to leave him, he said with some hesitation: “You have been so good to me that I wonder if I might ask you for one thing more. If you could, would you leave me fif- teen cents for coffee and doughnuts in the morn- ing?” That was the cheapest breakfast that he could buy. I said, “See here, kiddo, I hadn’t forgotten about the breakfast. I expected you would wake up with an appetite as I hope to, but I was leaving that till the last thing before I sain good night. But you don’t get off with any fifteen cents.” And I slipped some money into his hand. ; As I finally left, he looked after me with a long ing that would actually almost have touched the heart of a railroad detective. I suppose I had look- ed to that boy somewhat like an angel—an angel in disguise, of course—very much disguised—in fact, hardly recognizable in the role. But nevertheless more angel than devil. Tho, confidentially, my phy- sician, who has, I suppose, as few successful, if fatal, operations to his discredit as any man in the pro- fession, tells me that so far he cannot find a wing sprouting on either shoulder of mine. But let us hope! After I got home and to bed, that kid lingered in my mind, or perhaps in what, in moments of spir- itual exHaltation, I am pleased to call my con- science. He had said that in the navy he had been © used to at least foods, shelter, and clothing. He could not endure much longer the present hardship to which he was not used. He had had his fill of the navy, but if worse came to worse, he would have to re-enlist. Now if he or any other boy really picks the navy as a career, I’ll not quarrel with him; I'll simply refer him to the psycopathic ward. But here was a chap who had had, as he said, plenty of it, Yet he might in desperation go back to it. He got on By C. A Moseley my mind. The very next night I went again to the district, determined to find that chap and, by. some hook or crook, tide him over till he could find a job in civik ian life and get on his feet. I combed the district several times. Again and again I went to the pool ~-hall where I had first found him, thinking that some instinct might lead him back there for a. reappear- ance of his angel. But owing probably to a faulty religious education, his faith in angéls must have been weak. Faith had not led him to expect a sec ond reincarnation. Or, more flattering thought to me, possibly he felt that owing to my goodness I had been snatched up by a fiery cloud and tran® lated to heaven—or snatched up by the police and deported as an undesirable citizen..Take your choice of the theories; the price is. the, same. I have never seen the boy since; tho. on the, fol- lowing night I again combed.the district. My, guess is that, aftér one night in a real bed, the luxury of the thing had sent him to the recruiting office to join the navy again. Probably now he is somewhere én the seas, polishing ‘brass or an officer’s shoes. Must you have a moral to this tale? Here it is. As soon as a young fellow in a recruiting office signs on the dotted line, his economic problem is solved. From that moment, food, clothing, shelter, medical and dental service fall on him like manna from heaven. But let him try to go out to do productive work, in contrast to the unproductive service of the army or navy, and the situation is different. He will not be hired unless the boss can see a way te make money out of him. And if the boss can’t see it that way—he may sleep in empty tool boxes and go hungry. : Ruskin somewhere says that we feed, train, and dress men for the labor that kills, when we ought to feed, dress, and train them for the labor of life. That's a mouthful. ‘So that is the moral. The sequel will never be written unless I again sometime run across that pleasing young Italian-American—and I might not even recognize him if I did. And the angel has be- come such a devil, that by no chance would he know me again. aa The Wages of Patriotism. A Guitar in the Rain - N a rainy day in the fali Don Pancho came to sponge. The dampness creeps into every cell and corpuscle. It reaches the marrow in your bones, The air hangs low. The breath of the stockyards ‘erawls into every pore. Like the slimy tentacles of @ monster. j O* a Tainy day in the fall Don Pancho came to Chicago from Mexico. With Don Pancho came his brother.. Their wives. Ten children, The Madison street car stood near the North- western station. The conductor fumed. “Step lively, “there!” The rain tears your nerves into shreds. “Come on, shake a leg!” Don Paneho rushed to the car. The conductor eursed. Don Pancho carried a guitar in his hand. ‘A guitar With ribbons. Red, white and green. Mex fean colors. “Andale Mujer.” Maria followed. And then the rest like beads on a string. Jose, Conchita, Jesus, Pablo,, Esperanza, more—eight more miserable lit tle humans. Excited. Bustling. Bundles, Color. Don Pancho struggled, pushed, encouraged. “Hur- ry, careful! Conchita, don’t lose that bundle. Jose, stand aside.” s : The conductor slammed the doors and cursed the rain, He cursed the day. The company. The job. The goddamned foreigners. 3 But Lon Pancho spoke no English, Valgamo Dios, “The fare senor? How much must one pay? And for the little ones?” The conductor cursed again. One two, three, six small children, “Pay only for eight, fifty-six centavos, senor,” I volunteered. “Ah, Senor, muchisimas gracias. We are strang- ers here.” Don Pancho bowed. Maria bowed. Jose nudged Conchita. “The Senor will help us.” The Senor paid the fare. He directed them to their seats. ‘ “One can sit anywhere in the car? All is one class?” =. ‘The Senor secured transfers. He arranged every- thing. Si, he will direct them where to change cara, “Muchisimas gracias, Senor, You are very kind to us pobrecitos!” The conductor cursed the arrangements. He cursed the Senor. He cursed in colors as vivid as those in the entourage of Don Pancho, “CVI, SENOR. Woe are from Sonora, Dispensome, unmomentito..., my guitar. One must be careful, It is so little, but then life gives so little to the worker. Is it not the truth, Senor?” Don Pancho saw the guitar secure with a loving tenderness. “Si, Senor, we come to work in the stockyards, My brother and I. One brother~ is now working there. “You will get rich?” “Ojala, But, no... my brother ts not rich, The children will go to school, Senor, I will work, Maria can still work a little. Jose is growing up Maybe ++.» If Dios fs good... = By Walt Carmon ALSTED STREET. “Maria. The children, Andale. Conchita be careful. Thank you, Senor. Thank you. Mil gracia&, May Jesus, Mary and Joseph .. .” : “Say, what the hell do you call this, anyway?” The conductor slams the door in disgust. “This is the car? Muchas gracias, Senor. Adios,” WATCH Don Pancho board the car. My thots go to my Mexican comrade who lives in the yards. For four years now he and his little family have-lived in the yards. For four years now’he and his little family have lived im one room. His little girl died last winter. There is seldom any heat. They sleep on the coki cement floor. Work is scarce. Wages are small, My comrade has been coughing a little, “It will pass,” he assures me, “NW /TIL gracias, Senor, Adios.” The car moves, To he stockyards. Maria waves a gratefyl “Adios.” The children smile, Don Pancho waves “Adios,” again. He grips the guitar in his hand, The ribbons have become wet. They droop a littla The car is swallowed up by the rain and fog... the yards eee WILL work, Maria can still] work a little, Jose is growing up...” Work. The yarda, “My, guitar, .. life gives the worker so little, Senor, does it not?” The rain drings a weird, depressive feeling tn its dampness. I walk thra the and curse the brant, vivid curses of the conductor, ona