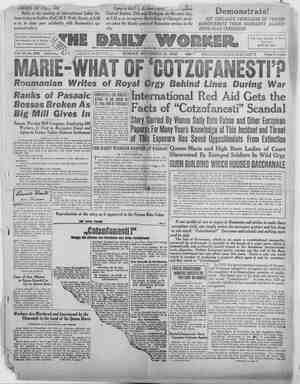

The Daily Worker Newspaper, November 14, 1926, Page 9

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

4 ad mt in ‘Chicago, and gave it revolutionary leader- Pp. r over 20 years the question of the eight- ar di’ had been “legally” agitated. Then, in 1884, wml - of unions determined that May 1, 1886, should set for its inauguration. At the beginning, so long the idea scemed a plaything to be dangled just out labor’s reach and keep it contented, it received the thusiastic support of the bosses, As the day set proached, however, and it became evident that labor 8 in dead earnest, no longer humbly beseeching for 3 passage of laws that would never be put into ef- it, bit ready to take what it wanted by its own or nized strength, then capital completely changed its ny As trade after trade prepared to strike and the gov ;|aent assumed nation-wide proportions, the press ‘oh| imto hysterical denunciation of the movement Louis Lingg } am anarchist plot. Im Chicago, the center of the movement, the eight var plan took tremendous hold on the workers’ tmag- ations, Unions tripled their membership. . New ions were organized, Altho Powderly, chief of the By Amy Shechter movement in the back (for which he was duly lauded by the capitalist press), the rank and file of the Kgot L. unions gave it wide support. Night after night Spies, Parsons, Engels and the other leading Internationalists addressed eight-hour meetings and helped in the or- ganization of new unions. On the Sunday preceding the first, they held a great mass meeting of over 25,000 on the lake front, and a visiting German pronounced it more imposing than anything of the sort he had seen in Paris or Berlin or London. By this time employers were panic-stricken. The market was shaken, stocks declining. Calculations were published to show that the reduction of hours would mean the loss of hundreds of millions of dollars of profits. Desperate measures were being planned to smash the movement. “A short and easy way to settle it,” wrote the New York Herald, “is urged in some quarters, which is to indict for conspiracy every man who strikes and sum- marily lock him up. This method Would undoubtedly strike a wholesome terror .nto the hearts of the work- ing class. Another way suggested is to pick out the leaders and make such an example of them as would scare others into submission,” Extensive military preparations were made as May 1 approached. Hundreds of Pinkerton stool-pigeons and sluggers were hired by the concerns where a large number of men were expected to go out. “The die is cast” wrote Spies, in an editorial in the Arbeiter Zeitung. “The first of May, whose historical significance will be understood and appreciated only in later years is here.” Then, after reviewing the growth of the movement from passive pleading to ac- tion, he continued: “That the workingmen would proceed in all earn- estness to introduce the eight-hour system was never anticipated by the confidence men; that the working- men would develop such a tremendous power, this they never dreamed of. In short, today, when an attempt is made to realize a reform so long striven for; when the exploiters are reminded of their promises and pledges of the past, one has this and one has that to give as an excuse. The workers should be contented and confide in their well-meaning exploiters, and sometime between now and Doomsday, everything would be satisfactorily arranged. “Workingmen, we warn you! You have been deluded time and time again. You must not be led astray this time. s “Judging from present appearances events may not take a very smooth course, Many of the exploiters, aye, most of them, are resolved to starve those to “rea- son” who refuse to submit to their arbitrary dictates, i.e. to force them back into the yoke of hunger. The question arises—will the workmen allow themselves to be slowly starved into submission, or will they. inocu- late some modern ideas into their murders’ heads.” _. May Day and Police Violence. With May Day came the greatest display of labor solidarity America has ever witnessed. By May 3rd the strike had become general. Some 200,000 were out throughout the. country (at a conservative capitalist estimate). In Chicago alone, 80,000. Spies, address- ing a meeting of some 10,000 striking luniber-shovers at 22nd St. and Blue Island Ave, that afternoon sud- denly heard a number of patrol wagons coming down the street and then volleys from the direction of the McCormick Harvester Works some quarter of a mile to the south. HaStening over to the works Spies found the police firing volley after volley into a fleeing crowd of men, women and children, The McCormick Harvester Works had long been a storm center in Chicago. In the spring of 1885 several men had been killed there by Pinkertons while striking against wage cuts. In Feb. 1886, another strike broke out when the men’s demands for the dismissal of a scab moulder was contemptuously refused. The plant reopened with scabs and 300 armed Pinkertons were hired to protect them. The situation was extremely tense and on the day of the reopening of the plant the Tribune had appeared with a headline, “Will blood be shed?” On his return to the Arbeiter Zeitung office, filled with the horror of what he had seen, Spies drew up a circular with a short description of the slaughter of the workers, and advising workers in the future to appear armed and ready for self-defense. The McCormick shooting had been no isolated in- stance. The Chicago police were notorious for their brutality in dealing with workers and the time had come when a worker’s only protection in that city was his own gun. In his “Reasons for Pardoning Schwab, Fielden, and Neebe,” Gov. Altgeld of Hlinois, who in 1893 unconditionally freed these three anarchists who had been sentenced to imprisonment instead of hang- ing, and had declared the whole trial’ to have been a preposterous miscarriage of justice, scathingly de- nounces the reign of terror carried on by the Chicago police againet the workers at this period, “For a num- ber of years prior to the Haymarket affair” he writes nights of Labor, sent out @ secret eircular knifing the | “there have been labor troubles, aud im several cases i | a number of laboring people guilty of no omense have been shot down ‘in cold blood... and none of the murderers were brought to justice. Peaceable meet- ings were broken up and raided.” Citing a number of cases of police violence in strikes in 1885 he says that the police under the leadership of Capt, John Bondfield “indulged in brutality never equalled be- fore;” and that in the spring of the following year, 1886, “the police brutalities of the previous Year were even exceeded.” The Haymarket Meeting. The day following the McCormick shooting, May 4th, a number of unions called a protest meeting to be held that evening at Haymarket Square “for branding the murder of our fellow workers.” It was a stormy evening and the meeting was not very well attended. The mayor of Chicago, Carter H. Harrison, attended the meeting and left at ten o'clock concluding that it Was ga peaceable assembly. He told Capt. Bondfleld that he could issue orders to his reserves to go home. A downpour was threatening and only a couple of hun- dred remained at the meeting. Suddenly some 200 policemen marched down on the crowd which Fielden, the English anarchist was addressing and began vie- iously clubbing them right and left, and firing. Sud- dently a bomb burst among the crowd, wild excitement ensued and a number of workers were killed (the actual number was never established), scores wounded, and seven policemen killed and sixty wounded, And now the capitalist organs were easily able to work up a mad wave of hysteria against every mili- tant in the country. The eight hour movement was smashed. Hundreds of arrests were. made and finally eight selected to stand trial in Chicago: Spies, Parsons, Fielden. Fischer, Schwab, Spies’ assistant on the Ar- George Engel . Adolph Fischer beiter-Zeitung, Neebe, and Lingg. Parsons was not to be found at the time buf came and gave himself up to the police preferring to stand trial with his*eompadee” The Anarchist Trial The trial was the wildest of wild travesties of jus- tice. To start with, instead of the jury being drawn in the usual manner, by lot, Judge Gary appointed a special bailiff to go out and get together a jury of his own choosing. When this bailiff’'s method of procedure was questioned he replied: (Altgeld vouches for this) “I am managing this case and know what I am about. These fellows are going to be hanged as certain as death.” The prosecutors constantly harped upon the fact that most of the men were “foreigners.” Spies wrote, no criticism could be made of “such wise and intelligent men as Mr, Grinnell and his jury for hanging miscre- ants who ‘have shown so little discrimination in the selection of their birthplace. Society must protect itself against offenses of this kind.” Altgeld showed in his review of the case that first of all the jury had been packed, then wholesale bribery and intimidation of witnesses resorted to, that the “de- fendants were not proven guilty of the crime charged -inwbhe indictment,” (none of the defendants could be at all connected with the bomb throwing), and that “the trial judge was either so prejudiced against the defendant or else so determined to win the applause of a certain class in the community that he could not or did not grant a fair trial.” The actual bomb-thrower was never found. Every indication pointed to the fact that it was provocateur’s frame-up and later a number of facts came to. light that tended to show that the secret service had pre- knowledge of the whole affair. A number of such bomb scares, but with less tragic consequences had come to light in various cities at the period. Czarist methods ‘had been taken over wholesale by the republic, The conduct of the accused in court made a deep impression among the workers both of America and Europe. They used the court-room as a rostrum from which to proclaim the principles or revolution. Parsons went into a lengthy analysis of conditions in the United, States under the capitalist system and the need for revolutionary change. Engel described the long and bitter road of proletarian life that had made him a reyolutionist. Lingg’s brief speech was a cry of de fiance to his capitalist hangmen, ‘typica] of his bitter and passionate youth: “I repeat” he ended, “that I am the enemy of the order of today, and I repeat that with all my powers, so long as breath remains in me, I shall combat it. I declare again, openly and frankly, that I am im favor of using force... I despise you, I despise your order, your force-propped authority, Hang me for it!"