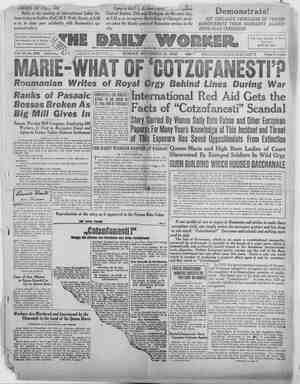

The Daily Worker Newspaper, November 14, 1926, Page 10

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

a 3 TWO LETTERS By MOISSAYE J. OLGIN, (Letter No. 1 was published in the November 6 issve of this magazine.) LETTER No. 2. Dear Maria: To ayoid scenes and voluminous talk, I have decided to let you know of my decision thra a letter, I have decided to part with you forever. I do not intend to return from this trip te what we fraudulently termed our heme. Frankly speaking, I do not see the need for explanations. We are fres people, a man and a woman, equal in rights and responsibilitie, It would have sufficed if I declared: “Life with you is no more acceptable to me.” Perhaps it would have been more dig- wified. You know I never believed in “explanations.” One of the sources @f frritation im our mutual life was your uncanny desire to weare a fab- rie of words around every occurrence. No fact 6xisted for you unless you enveloped it with wrapping upon wrap. ping of set phrases. You will not be _at sase until you have pui into well- rounded woris the “meaning” of oar parting. So be it I spoks about fraudulently calling our cohabitation a home. I mean what I say. We have never had a home. In your conception, a home was some- thing sweet, soft, pink, lacy and thoughtless. Yor wished every breath of real life, every experience which always carries with it strong currents and pungent smells, to be kept out- side of that yacuwm which you choose to call home. To me it was a waste ef time, to say the least. But it was more than that. It was degrading. What amazed ms in your mental pattern more than anything else was the ready classifications that always were at your disposal. Here was pub- lic life, here was privacy; here the world, here, we; here, experience, here, faith, religion, worship. You were mistaken in me when you ostraightforwardly assumed that I was against religion. You will be shocked if I gay that I respect real religion. A mighty force that grips you against your own volition, a fathomless yearn- ing for things beyond your reach, a total submerging of one’s personality with a gigantic objective power, why, this is beautiful, but this was not your religion. Yours was something perfumed, something evanescent, a thought thinned down almost to noth- ing, a yearning as gentle as the re- flection of sunzet late in the evening, the shadow of a shadow, the reminis- cence of a sound that is no more. Your religion, dear ‘Maria, was the pastime of decadent generations play- ing with futilities where real expe- riences are ‘too strong to stomach. This I cannot respect. Decadence is tantamount to rotting, to decomposi- tion. You do not expect me to respect the negation of life. You called it beauty. You consider this the greatest value in life. I may as well confess that it was this ready- made, pretty something, that fragrance of refined spirituality, that captivate. me when I first met you. At that time it seemed to me you embodiéd all tha; may soul was craving for from early boyhood. You know my “biography. .The son of a day laborer, raésed in squalor First, an apprentice in a blacksmith’s shop, then a youthful factory worker with a devilish hunger for the higher things in Hfe. A self-taught inte! lectual parvenu, who, thru long’ and weary evenings of poring over books thru crue] assiduity in trying to take ag large a bite of knowledge as his intellectual digestion permitted, was trying to patch up the apalling holes in his edifice of knowledge, only to discover that those confounded holes were growing in size and number. starving man full of corroding énvy of those who had the leisure and the fa- cilities to acquire knowledge. How mont! I early becang involved in the class struggle, and I was not the last among the comrades of my age, but lato my revolutionary ardor I person- ally brought in this.added envy for the cultural possibilities open before the bourgeoisie—an envy akin to pain. My class consciousness surely was not limited tp the problems of bread and butter, as yon chose to characterize it again and again, The revolution was for me a step towards the realization of this spirit- ual yearning of the working class, of which I considered myself only a more advanced ember. When ‘we confis- cated bourgeols houses, nobody knew with what awe I entered places which I almost intuitively considered tem- ples of beauty. I will mever forget two hours spent in the library of Ryabkov’s mansion, of which I was assigned to take inventory. What a wealth of taste, what a blending of colors! What.a mollifying combina- tion of lights, what an atmosphere of pure, delightful thought, and what beoks! What a number of well-bound, beautifully printed volumes! Never did my heart throb in the presence of ® woman ag violently as it did that evening when I opened one bookcase after another. When I met you I tnought the most exquisite flower of culture had come into my path, I never believed in saints—not since I was five—but you, Maria, actually seemed to exude a cer- tain radiance. With you and thru you I thought to reach those heights of “real” culture, the vision of which tor- mented my soul for years, You may not have noted what an infernal amonnt to labor ft cost me to adapt myself, at least outwardly, to your ways, to your standards of beha- vior. Iam a working man with strong - arms and a powerful body, I am used to wield a hammer,.a Shovel, a ladle of molten metal, a machine gun. You demanded gentlemanly manners, I molded myself according to your re quirements. My comrades — often mocked at my “excess of refinement,” calling me derogatory names in per fectly friendly good humor, I took the pain of breaking myself. I thought it worth while. Only on common ground could I meet with you to share that which you were to offer me, I thought. It took me some time to ‘Qenofey that you had nothing to offer. True, you were a fair representative of the culture of your class, but I had not known that that culture was shallow. It was a thin, glittering skin covering, a very selfish, self-centered substance. All your beauty, all your refinement, was, as the English say, skin deep. You had manners, you had ready-made patterns of conduct, yow had ready- made patterns of opinion, but it was all on the surface. You never know what it was to be storm-shaken to the very last vestige of your being. Since I have allowed myself to in- dulge in this futile frankness I may just as well tell you that your com- pliance was repelling to me. You were opposed to the revolution. Why didn’t you fight? I was an enemy of your class, a destroyer of the existence of those dear to you; how could you F ta, DEMOCRATIC” UNCLE SAM “PREFERS QUEENS? AL I idealized the college students, shin- | vd demigods moving in an atmos- phere of power, of spirituality, they were to my fervid imagination. How | longed to cast off the crudities, the :wkwardness, the humiliating con- sciousness of inferiority that I had wrought with me from my environ- rn a cE ES nL TTS Cotzofanesti _ethe shades of night were falling fast When through the Balkan darkness passed The Reaper grim. . :.A soldier died Without his nurse, his queen, and cried— “Cotzofanesti!”’ While peasants starved and workers went To prison for their discontent, The tyrant queen of all this hell Was nursing soldiers who were well - At Cotzofanesti. This nurse, this queen, the gay Marie, Had other business, as you'll see, With officers of greater vigor Than the poor boob who pulled a trigger _At Cotzofanesti. Like Messalina on a tear With nymphs and satyrs gathered there, The royal dame who ruled the nation Left little to imagination At Cotzofanesti, So when you’re asked why Queen Marie - Has mobilized a huge army Of soldiers strong and broad and tall, - You have, therefore, but to recall— - A Story seek peace in my arms? Why did you not kill me in my sleep? You con- sider yourself a romantic lady, you love to carry this sign of high emo- tlonalism, Let me tell you that for months after we became lovers I stil anticipated an act of violence on your part. I hardly went to sleepy without a lingering idea that you might kill me, after ali, You had not the strength to do it. You never thought of that. You found shelter and devo- tion in the enemy’s camp, and you gradually learned to talk his jargon. Is that romantic? Here I touch upon something funda- mental, perhaps the most fundamental, of all things. You are concerned with yourself alone. You think of the world only as a source wherefrom to draw conveniences and pleasure. It is al- ways you and the world, You are a veritable enemy of mankind; never for a moment do you forget your own self. I know this is not a personal peculiarity of yours. It is a charac- teristic of your class. But what value is there in culture, beauty, refinement, spirituality, when ft is alt for oneself, all, so to speak, for jndividual consump- tion? Theoretically, I had none of the individualistic propensities of the bourgeoisie. A live experience it be- came to me only thru association with you, ; Ah! you blamed me for coldness! You never knew that flame of exulta- tion when a man loses the conscious- ness of his self, when a man is capa- ble of throwing away his self as one throws away a discarded rag, because he does not think of himself, because the bigger universal thing had capti- ated him with such power that it stance. No, with all your refinement you never lived the life of the uni- verse. You recited your spiritualist poets, who, you said, were groping by sheer intuition for the things expe- rience can never achieve. What did will not be able to understand what I ‘| have just. written down, And then something else. Your ava- rice. You did not realize that you became somewhat like an aft drag- ging things into its nést. It was hid- eous, Maria‘ hideous! You seemed to ink that the revolution was made for the express purpose of furnishing a beautiful apartment for you, of se- curing you box seats at the opera. You even took it for granted that, being the wife of a state official, you had to wear jewels. I could not dis- suade you. It was too humiliating to argue such things. You thought it your privilege to shine in a lodge with a diamond ring flashing all sorts of colors in front of my comrades. You never thought of that, eh? To you it was beauty; to me ... The least said, the better. Dear Maria, I do not want to be untrue to myself and to you, I cared for you a great deal. I wish I had not become so much attached to you. You are lovely underneath and beyond your shell of bourgeois culture. I often thought yeu would be able to cast’ off the old Adam and Eve. I saw, I thought I saw, seeds of a future love- liness that would overshadow the past. My hopes have not material- ized, I waited long and labored pa- tiently. I hate to give up a task. As things stand, I must admit my ‘defeat. Better let us part, peacefully if we can, You will think of another woman, I assure you there fs none. This much you have done to me, that the women of my own class all seem crude and primitive to me. The theoreticians of our movement would say that associa- tion with the bourgeoisie has placed me in between the two classes—a white raven, as it were. I wish I had a sense of humor strong enough to laugh at my own plight. But let’s not talk of this, Good-bye, Maria, ahd be happy, if you can, If I am not mistaken, you will find some peace of mind in asso- elation with people of your own class. Be well, became his own life, his very sub °