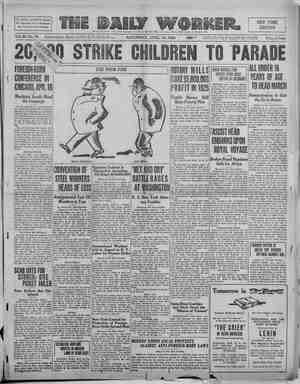

The Daily Worker Newspaper, April 10, 1926, Page 9

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

SA A ST Mysticism in the New York Theatres » By MICHAEL GOLD. UGENE O'NEILL is still America’s great dramatist. For he is hon- est; he has a fire in his belly; is bale- ful, grim, smouldering, passionate; he is not a “little Johnny Weaver” chorus girl of the arts, flirting skittishly with the emotions; he is a man. Everything he says seems as sin- cere as the raving of a gangster under the third degree, or a truck driver having his legs amputated after an accident: O'Neill suffers real pain; he has made art out of this pain. One respects this man; he has never sold out, One respects honesty that wears for ten years in America; it is rarer than black pearls. This is a nation of intellectual prostitutes; most young rebels at thirty become some- body’s hired brain; -the cities are full of slick, bored, purchasable sophisti- cates. Menckenism and. the disillu- sionment of the war have ruined whole generations. But O’Neill has endured. The Drift of Mysticism. HE American intellectual has come to the impasse where he believes in nothing—nothing except making a comfortable living. He scoffs as Bab- bitts; but he himself is deeper sunk in dollarism than the innocent, crude Babbitt. Many have accepted this state in the mood of the lady who took the “easiest way”—‘there seemed to be no other,” she cried between a sneer and a sob. But the best of the younger intel- lectuals are trying to fight a way out. They know that in Menckenism, or sneering, or posing as a rake, a super- man, a boulevardier, and a wise- cracker, there is no more solid nour- ishment than in cream-puffs and syn- thetic gin. The mind cannot live by froth, by negation alone. It must feel that life is moving somewhere. But life, in the United States, is only moving toward a great, crass, loud, selfish, luxurious machine—plu- tocracy. We are building a bourgeois empire -wilk-simother the world. And “s6° thé iiteltectuals swing to the opposite extreme and become mys- tics. If there are no answers in life they grope forward into eternity. Eugene O’Neill, because he’s so bitter- ly honest, seems to be one of those headed in the direction of mysticism. So are John Howard Lawson and other young writers. There is a strong ten- dency toward that on the stage and in books. This is alone real and it fights us with weapons of reality. To fight it back with shadows and vague sym- bols is to throw the battle entirely into its hands. The Great God Brown. pier newest play is built on a solid theme—the conflict between the creative and the acquisitive values in life. He handles his theme nobly, and with his undimmed dramatic genius. In form the play is experi- mental; this man never rests on his laurels, he is always pressing forward into virgin places, a pioneer. He ex- periments with masks in this play. There are two men and a woman,.and they show each other only the masks all of us wear. One made is an art- _ ist; the other is the Great God Brown, the type-symbol of American pusher, go-getter, exploiter, the sterile money- grabber who sneers at the artist, yet envies him his rich treasures of the mind, The conflict between creator and exploiter, presented in power scenes, reaches its climax when the artist dies of despair, and the American suc- cess steals his mask, in order to pos- sess the woman both have loved. But the deception proves a failure; Brown is still sterile under the stolen mask. The play is capable of many inter- pretations, and it is true, also, as the fattest of our New York stage critics have declared, that its symbolism be- comes confusing at times. What is clear is O’Neill’s burning hatred of dollardelirium. . All his plays have a social over- tone, even when, as in this one, mys- ticism rides over their surface like a fog, blurring outlines and meanings. Why so many Bible quotations? That hook of old pastoral poetry should feel as useless to a young modern writer living in New York as to a scientist. It is a fairy-tale, fit for only funda- mentalists and dilletantes, but we are in deadly earnest. We want real an- swers to our problems, not mystic soothing syrup. O’Neill is in deadly earnest, but_he seems caught in the mystic wave that is creeping into American literature. Lawson’s Nirvana. Jom HOWARD LAWSON has had a more virulent attack. This man is the author of “Processional,” pro- duced last season, and as yet the most powerful, most sinrere, most stimulating and ground-breaking play that has grown out of the rich, rank soil of the American labor struggle Read the book, if you haven’t seen the play; it is really a classic. Lawson’s newest play, “Norvana,” was produced a ‘few weeks ago in Greenwich Village. It was badly pro- duced; the actors gave off a faint flavor of ham. (Few American actors are convincing in any play where the characters are really intelligent and modern.) The play was written in the mood of Dostoevsky, a wild, lurid rending, epileptic and impossible ac- count of the God-seeking of a group of American intellectuals. The hero searches for a faith in bourgeois America; and as there is none, ex- cept the national belief in the eagle on the dollar, he goes stumbling for- ward to some wierd electro-magnetic god, who is finally revealed to him and to us by a ludicrous Christian Science miracle at the last curtain. Lawson’s attempt at truth was mag- nificent. He was trying desperately to break thru the barbed-wire stock- ade that hems the American intel- lectuals into @ common compound with their enemies, the sterile Bab bitts. But he failed. Lawson has wit, he has dramatic skill second only to O’Neill, he has passion, sincerity, fine cool brains, youth, courage—he has everyfhing— but he cannot break thru the bour- geois philosophy. He has hammered ne philosophy out for himself, and has to go god-seeking, His play was-@, magnificent 4aiinne, and it should have been an everf tiete magnificent success. This Lawson has the stuff of a world playwright in him. Only O’Neill is his master in this country. But he is doomed if he con- tinues on the path to Nirvana. He must go back to the realities of the West Virginia miners of his last play; he must stick to.the earth, where he is strong. Goat Song. HE Goat Song, by Franz Werfel, one of this season’s importations of the latest fashionable foreign mod- els by the Theater Guild of New York, was also a blend of mysticism and revolution, Revolution—among vague foreign peasants, some three centuries ago, in a mythical country, not America. Revolution—dolled up in pretty Maxfield Parrish settings, with charm- ings groupings, and nobody gets hurt. Revolution—sprung from the sick subjective brain of a student, instead of from the need of the masses, Revolution—symbolized by @ mon- ster who has been pent for years in a cellar, (And why-such a symbol? Surely the monster is capitalism.) Revolution—not something real, not something that cuts into the lives of a New York audience, but something in a theater. Something ending in Sun- day school bible lessons. There were great moments in the play; and perhaps a New York audi- ence cannot digest anything like strong red meat in the way of revo- lution. Maybe this is the limit. But I would like to see the Theater Guild put on a revolutionary play about the New York garment workers, with real workers massed on the picket line, New York cops pounding them, and an audience of New York clothing merchants writhing guiltily under the tongue-lashing of the agita- tor-hero. That would be social revolution in the theater, The Theater Guild does some really splendid things; despite its strange prejudice against American writers, it makes sacrifices for tlle new experi- mental stage, Why doesn’t it build a little studio Keep Religious with Cal “Our institutions” must be made to rest on the foundation of “reverence for religion,” which will help to keep (the working) class from asserting itself against (the capitalist) class, said the cool Coolidge this week, to the journalist’s congress. where it can give young revolutionary American playwrights a real chance to rei OF. succeed—at least to learn? In five’ niot“need to import the works of the parlor-mystic, Herr Werfel. Personally, I believe there is more hope for the American theater in a failure by Lawson, or in even a crude native success like “Is Zat So?” than in a hundred imported Goat Songs. One can learn a few things from others, but not how to create. This is a lesson, too, for the workers. They must experiment in order to find their own culture, which will not be mystic, like that of the bewildered bourgeois intellectuals, but real and dynamic as the barricades. By HENRY. NE of the many important features of Easter in the Roman Catholic church is the baptizing of eggs and sausage. Last Saturday was the day set aside by the church for that par- ticular function. Passing one of the Roman Catholic churches in the near northwest dis- trict of this town, I noticed a large assembly of boys and girls in front of the church, each carrying a small bas- ket, the contents of which was neatly concealed under a snowy-white nap- kin. Drawn by curiosity, 1 managed with some effort to elbow my way in- side the church. Lo, and behold! what greeted my eye? ‘The priest in a long black skirt covered with table cloth, small book im one hand, funny-looking whist broom in the other hand, sur- rounded by a crowd as large as the one outside, was murmuring some mysterious words in Latin to the amazement of the black-faced boys and girls surrounding him. From time to time he ‘dipped the bushy end of that whist broom in a shallow ves- sel containing water, and with digni- fied motion of his hand sprinkled the tables upon which were hundreds of small baskets, each containing sau- sage, eggs, chunks of pork chops, or a cut of beef, dressed with green leaves. The contents of each basket upon the table were exposed to_ the precious holy water which the priest freely showered upon the baskets with his whist broom. I asked one of the boys who ap- parently was owner of one of the bas- kets: “How will you find your basket when the ceremony is over?” “Oh! I keep my eye on it all the time; I can see it now,” he told me. o ——_—_—— SO OOO eee ee ere |\Sanctifying Sausages EN the holy ghost suffictently permeated the cold storage eggs, the embalmed sausage and pork chops, the priest closed his Latin book, com- mitted the whist broom to the care of his small pug-nosed assistant, and the show was over. By cross-motions in the air with his hand in the direction of the loaded tables the priest signi- fied that by his magical words the holy ghost was firmly fixed in the sau sage, eggs, pork chops and beef, and it is ready for the christian table. Immediately the crowd of children surrounded the tables, hunting for their respective baskets. Several ef derly women tried to maintain order and acted as referees whenever com troversy arose as to ownership of bas- kets. At any rate the children mirac- ulously found thetr baskets, or at least it appeared to me that each one got his or her basket, as they poured thru the wide open door street. S I was about to leave the place my attention was directed to group of boys and girls, each one with a small milk bottle in his hand. In the midst of them stood the priest’s assistant, wildly gesticulating with his hands to the growing crowd of chil- dren, “Don’t! Don’t! The priest may see it!” he plead in a subdued voice. “This is all the holy water we have today and the ceremony is not over yet!” Finally I heard the assist- ant say, “Aha! the thieves of holy water!” “The thieves of holy water,” I re- peated as I left the holy house of god, just when another crowd with baskets filed with we oi eggs and pork to pour into the sanc- tuary.