The Daily Worker Newspaper, September 27, 1924, Page 6

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

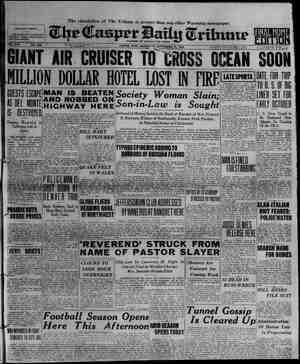

a oe wee The Proletarian Will to Power By MAX SHACHTMAN. HE history of the working masses is also the history of their at- tempts, to free themselves from op- pression; it is the history of struggle against the ruling class. : The oustanding struggles of the working class against the bourgeoisie in the nineteenth century were the Chartist movement in England, the revolutions of 1848 in France and Ger- many, and, most important, the Paris Commune of 1871. It is of these that we shall treat here. The Chartist Movement. The conditions of the British work- ing class at the middle of the last century were indescribably horrible. The Reform Bill of 1832 had been of advantage to the middle class alone and left the workers without the suf- frage. Five years later, one of the numerous radical societies that had sprung up all over England, the Lon- don Workingmen’s Association, drafted a six points petition which later became the People’s Charter. It called for equal electoral districts, universal male suffrage, annual par- liaments, no property qualification for M. P.’s, the payment of members and vote by ballots. To achieve this aim, no revolution would be necessary. But attracted to the Chartist movement were the leaders of the “miserable proletariat of the North,” the physical forcists of the Bronterre O’Brien type who made it plain that the Charter was the preliminary step to ‘social equal- ity. : : Thus, J. J. Coombe, a Chartist jour- nalist, answered the question as to the object of the People’s Charter by writing: “Social equality means that tho all must work all must be happy. And now having answered the inquirer as to what I consider social and political equality to mean, just let me ask you, kind reader, one single question, do you expect that such a state of things, will ever come to pass, by go- ing down on your bended knees and praying. for it? Be not decieved, your tyrants will néver concede justice till they are compelled; never will they yield to your démands even till they are overcome by fire and sword, and driven or exterminated from the face of the earth.” The Chartist: agitation was given tremendous impetus by the severe crisis of 1838. The movement gained thousands of adherents. A conven- tion which met in February presented the first petition, and, while awaiting the result, considered what its policy would be in the event of rejection. The physical forcists were increasing their influence to the detriment of the moral forcists led by Lovett, The situation, considerably aggravated by the bloody riot in Birmingham, and the arrest of Lovett, brot the conven- tion to declare a general strike. On second thot the strike call was with- drawn, but it was too late. Welsh miners appeared in armed bands bearing down on Newport with the in- tention of capturing the town and proceeding to Cardiff. At Newport they were met with a fusillade by the hidden crown throops and retired in confusion. Nothing To It - The height of Chartism had been reached and from then on, despite the sporadic outbursts, the movement was doomed. The final blow was not only the ridiculous failure of the sec- ond. petition but also the repeal of the vicious Corn Laws of ’46, the pass- ing of the remedial Factory Acts, the rise of the standard of living accom- panied by the revival of a stronger trade union movement. The fiery appeals and leadership of Feargus O’Connor, O’Brien and John Frost were forgotten as the hungry masses rushed to pick up the crumbs that were falling from the table of England’s overstocked prosperity. They were lulled to sleep by the trade unions under the pacifist lead- ership of the predecessors of J. H. Thomas and Frank Hodges. to .come to revolutionary TYrance., “glorious workingmen’s revolution . There he gathered the members of the League of Communists and pro- ceeded to the Rhineland to establish the historic Nue Rheinische Zeitung. His brilliant contribuisons to its col- umns- remain the outstanding results of the German revolution. In them are concentrated the history, the lessons, the criticisms, and the com- mendations of the German and French revolts. “Revolutionary upheaval of the French working class, general war— that is the index for the year 1849. And already in the east a revolution- ary army, comprised. of warriors of all nationalities stands confronting the old Europe represented by and in league with the Russian. Army, already from Paris looms the Red THREE HEROES OF MASS MURDER LUDENDORFF NOSKE MUSSOLINI 9,750,000 Dead The Spectre That Haunted Europe. For almost a decade the wave of Europeah revolution was at ebb. Then, suddenly, following on the heels of the Communist Manifesto— its memorable beginning: “A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of Communism:” its ominous warning —*Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution”—came the uprisings of 1848 in France, Germany, Hungary, gnd Italy. In France the workers, who could no longer stand up under the horrors of unemployment after the severe cri- sis of the winter of 1847, participated in a demonstration; soldiers attacked them; a riot began; the king fled; the provisional government was pro- claimed by Lamartine, and the nomi- nees of the workers, the socialists and radicals, abdicated before it. Marx, who so early as 1843 in a letter to Arnold Ruge had predicted ‘the revolutionary wave, was invited 25,000 Dead 20,000 Dead Republic!” wrote Marx. Prophetic. words. The revolt of the- Parisian prole- teriat, lacking in consciosness and disciplined leadership,. failing to real- ize that there was only one means, in the words of Marx, “of shorten- ing, simplifying, and concentrating the torturing agonies of society—only one means—revolutionary terrorism,” was butchered by the troops of Cay- aignac in the frightful days of June. The German uprising, a _ reflex largely, of the French attempt, rose as easily as it was put down. The revolutions were petty bourgeois, with few proletarian elements. Order was restored by the bourgeoisie, the prol- etariat vigorously suppressed, so that commerce and finance might continue unhampered by turmoil! But from Paris loomed the Red Re- public! The Glorious Commune. + » » took undisputed sway of Paris.” The most mature and im- portant example of the proletarian will to power of the nineteenth cen- try was being exhibited in swift, dra- matic scenes. The fall of the Little Napoleon, the failure of , Thiers’ treacherous attempt to seize the can- non of the National Guard, the frater- nization of the troops of the Line, the rise and proclamation of the Com- munes of Creusot, St. Etienne, Lyons, Marseillies, Narbonne, and Paris— all followed in bewildering succes- sion. . Paris, whence all but the revohr tionaries had fled, established the workers’ dictatorship over all France. Marx had advised against the revolt, He had proposed, instead, the crea-: tion of a strong proletarian fighting organization, taking advantage of any freedom they could squeeze out of the code of republican “liberties” and with growing, disciplined army of revolutionaries, await the propitious moment to strike for victory. But the Commune was nevertheless established. (Revolutions have that habit of not waiting on anyone!) It was the first proletarian dictatorship and it had its numerous shortcom- ings, weaknesses. It failed to lay hands on the Bank of France; it did not .deal summarily with. traitors in its own ranks; it had the vain hope of securing peace with Thiers; only at the last hopeless moment, did it put Delescluze in charge of the army in place of the incompetent Cluseret, or Rossel. But then, it was composed of such diverse elements as Blanquists and members of the First International; radicals and revolutionaries; serious rebels and dabblers; honest men and brave like Delescluze and scoundrels like Blanchet or mouthers like Felix Pyat. Yet it was the working class in power! The Commune of the peo- ple’s army, the demolisher of the Vendome column, the seizer of aban- doned factories, the “ally in a conflict which can only end in the triumph of the communal idea.” The Commune lasted a little over two months. It was drowned in a sea of its own blood, drawn by the wretch Gallifet. It will be “foréver celebrated as the glorious harbinger of a new society,” Marx wrote in the valedictory which was also the fare- well to the First International. The workers of Europe were not to rise again for a half century, with the interlude of the heroic Russian revolution of~1905, when Lenin _ first recognized the Soviets as the form of the proletarian dictatorship. But when the proletarian will to power again expressed itself, when the Rus- sian giant rose and felt its huge strength, it had behind it the lessons of the revolutionary nineteenth cen- tury. It had as its staff and sword the teachings of the revolutionary Marx; as its leader, the, iron-willed Lenin. In the image of the First In- ternational it bore from its loins the Communist International, carrying the red torch to every corner of the earth, giving inspiration, hope, and belief in the coming of the new so- ciety, in the proletarian will to On the 18th of March, 1871, the!’ power! By Nathaniel Buchwald (IMPRESSIONS OF THE LaFOLLETTE MEETING IN NEW YORK) supposedly has swept and swayed and|—the chairmap, the preliminary | which illumines Communist rallies of sitrred up the well-advertised mass-| speakers, “Fighting Bob” and all. size, which was characteristic Of so- Comrades, there is nothing to it. I mean that LaFollette hullabaloo. The. big meeting was a bust. It was hollow, and the fine acoustics of Madi- son Square Garden gave full reson- ance to this hqllowness. : To confess, I was all tense as I proached the Garden, I was read summon up all the clear thinking Communism has taught me to stand the onrush of that blind compelling enthusiasm, of the revival- ist progressivism (1924 brand) which ZEEsS es that are behind LaFollette. But I Perhaps I can impart to you a sense | cialist gatherings of did not have to call upon my reserves | of that gathering, its color, its of hard Communist thinking. A primer | ual timbre, its moral was more than sufficient. Not even ajdead from LaFollette spirit- | trace- of it, not a quiver of inspira- fabric. It was|tion, of splendid madness, It was all down or from |sport, all fun. People applauded, the audience up. The noise at the |whistied, yelled in a light-hearted candidate’s arrival was a spiritless,|manner, bantering as they did so, perfunctory merry making. Merry mak- | laughing at their own childlishness of ing is the word. I looked at their |joining in the noise. This still-born faces, I wanted to detect in them that jovation would have run its course in inspired glow, that irresistible faith, |two or three minutes, and if it lasted