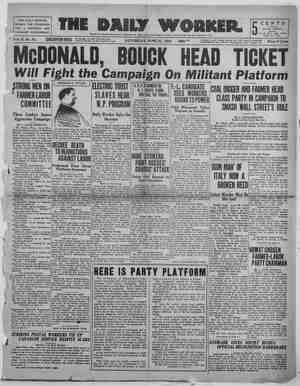

The Daily Worker Newspaper, June 21, 1924, Page 5

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

i a anes mem ap P “The idea becomes power when it pene- trates the masses.” —Karl Marx. SPECIAL MAGAZINE SUPPLEMENT THE DAILY WORKER. JUNE 21, 1924. SECOND SECTION This magazine supple- ment will appear every Saturday in The Daily Worker. Impressions of Russia - EFORE we plunge into a detailed analysis of the Russian economic and political situation, let us cast a glance at the outward appearance of Russian life. We know from statistics that agriculture in Russia has reached 75 per cent of its pre-war output and industry is approaching the 40 per cent mark. To the prejudiced mind it seems a low level, especially in view of the fact that even in 1914 this was not a highly developed industrial country. However, figures alone can- not give an idea of the realities that make up the life of a people, and if comparisons are necessary, they should be made, not with pre-war years of prosperity and economic ex- pansion, but with the years of civil war and revolution, years of economic gressive, he is glad to be left alone, whicn seldom happens since the sov- ernment of the workers and farmers is after each of his manipulations. The Nepman may fill the theatres of the more conservative kind; he may sper.d his nights in the shady cabarets that were opened by his fellow Nepmen to satisfy his bourgeois tastes; he may have a banking account and a dia- mond on his finger. Yet, he is only tolerated. He has no rights. He does not vote. He does not serve in the Red Army as a weapon carrying soldier. He does influence thedestinies of the country. He is a temporary evil. Eco- nomically he is neither a leading man- ufacturer, nor a mine operator, nor a railroad magnate, nor a financier, all industries, foreign trade and banking business being in the hands of the gatherings of trade unions, clubs of workers and Red Army boys, schools and faculties of workers, demonstra- tions of workers. It is enough to have a stroll thru a Russian city to recog- nize that this is a country under the dictatorship of workers. The prevail- ing garb is that of the worker. The women’s headpiece is a red handker- chief. The general tone of life, man- ners, customs, are those of the prole- tariat. There is no roughness or crudi- ty in this life, but there is simplicity, directness, amity and a disregard for petrified conventions. The difference between the worker and the so-called intellectual is gradually disappearing. In my dealings with great numbers of Soviet functionaries and trade union people, it is sometimes almost impossible for me to define whether LUE ae A DEMONSTRATION OF AGRICULTURAL WORKERS IN OSAKI | deterioration, general misery and hunger. The present writer was in Russia in 1920-21, and .the impressions that forced themselves upon him from every direction, produce the picture of a patient who recuperates after a dangerous sickness. When the con- valescent is by nature a vigorous fel- jJow with a sound body and optimistic mind, the sight is hopeful, indeed. A country full of hopeful activity, this is how one finds Russia in the spring of 1924, It is, first of all, a proletarian coun- try. Talk what you might about the new economic policy, about the ap- pearance of the new bourgeois, about his nefarious influence on the poor bedevilled Russian simpletons, when you are in Russia you know all this is bunk. The Nepman is not a leading figure, he is an outcast, He is not ag- proletarian state. What the Nepman’s activities are confined to is internal trade of the more petty variety, espe- cially between city and village. Here he is competing, and often successful- ly, with the government and co-oper- ative stores, but his competition only stimulates the state and public agen- cies to more efficiency and better adaptation to the peculiarities of the market. In the sum total of economic and social life, the Nepman is of small account. Nobody is afraid of him, and he himself is aware of his subordinate position. Life in general is dominated by the workers in the cities, by the peasantry in the villages. What you see and what you come in contact with on every step is a government of workers, state and city officials them- selves former workers, conferences of workers, conventions of peasants, a my interlocutor is a former mechanic or a former student. Soviet life has a leveling effect. Former workers have. acquired a great amount of in- formation. Former intellectuals are losing their aloof air and their con- sciousness of being a chosen race. Work of construction is bringing to- gether all the live elements of the proletarian state. Present Russia is a busy country. I have discovered a monthly magazine called “System and Organization.” This is characteristic. System and Organization is the slogan. The Rus- sian worker, the Russian factory man- ager, the Russian builder, the Rus- sian state official, the Russian trade union leader, the Russian collector of revenue, the Russian agriculturist, the Russian public trader have to re- linquish the old sluggishness, the laxity, the “work is no beast, it won't By Moissaye J. Olgin run away to the woods” psychology of jezarist times. We have to learn how ito do business, or else we will not jretain or develop the conquests of the lrevolution!—this is the prevailing jidea. For an outsider who thinks of ‘revolutions only in terms of insurrec- jtions, barricades and red banners, it may be strange to discover that a revolution is busy with calculating |indices of prices, with stabilizing the currency, with increasing the output lof manufactured commodities, with improving transportation, with tinker- ing in a thousand and one fashion {around the economic apparatus of the country. The proletariat has con- 'quered power. The proletariat has taken into its hands the economic or- | ganization. It could not improve it as long as it was forced to fight for its supremacy against external and in- ternal foes. Now that power is se- cured and foreign intervention is not likely, work of reconstruction becomes the most imperative problem. And the work is carried on on a gigantic scale. The first task was to free the state organization from its superfluous ballast. In the times of compulsory labor and state rations, everybody had to be given some kind of work, if only nominal. State offices were overcrowded with functionaries who did very little, who could not do much because they did not know how and because the average vitality of the population was 60 per cent below normal, In the last two years the state machinery has been undergoing a vigorous cleaning. The incapable or inactive had to go, The remaining were given a living wage so they (Continued on page 8)