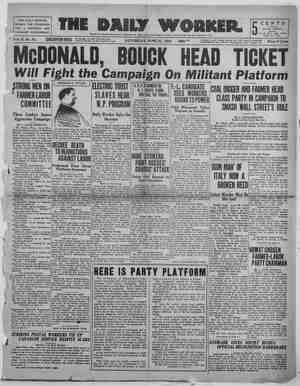

The Daily Worker Newspaper, June 21, 1924, Page 11

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

“TI wonder,” said Fellow-worker A to Fellow-worker B, as they strolled inside the inclosure with that leisure- ly nowhere-to-go sort of gait prisoners fall into, “I wonder just what that lit- tle old button with three stars and the three letters, I. W. W., stands for now- a-days.” - ‘If you mean that for a question,” replied B, “I'll tell the world it stands for a good deal now-a-days. ‘That’s sufficiently ambiguous to merit mé be- ing crowned with the same laurel as the present editor of Solidarity,” he added urbanely. “Well,” rejoined A, “there’s some doubt if it’s laurel or poison oak he’s wearing. But, seriously, I’m hanged if I'd know the I. W. W. now for the one I joined and went to jail for. These three stars once stood for ‘Education, Organization and Emancipation.’ And the three letters meant the ‘Industrial Workers of the World.’ And that meant a lot of other things, good things. Industrial unionism to start with, but that was only a tool to work with and not the end—not the whole aim. It was only a ‘road to- freedom’ not freedom itself, a tool of the com- ing revolution, not the revolution it- self and intoto. Now the chairman of the G. E. B. says that all ‘highbrow books of Marxian ideas’ should be burned—that’s ‘Education’ Then all workers’ organizations who want to organize with us are refused and in- sulted, from the Canadian Lumber Workers to the Red Labor Union In- ternational. And that’s our ‘Organiza- tion,’ I suppose. And then there was the third star that stool for ‘Emanci- pation.” Now the same bunch that would give us ‘Education’ without Marx’s books—without any books in fact—say, “What we want is to settle immediate problems.’ Which really means that they are afraid to discuss even the revolutionary problems of today in the spirit of the I. W. W. They pretend to be theoretically op- posed to the Sovicts when really they’re only scared of going to jail if they indorsed them. But is all this —and a thousand other things—revo- lutionary? For they still cling to that sacred word. Tell me, are we still the vanguard and not the camp followers, of the American revolution? Is this what Joe Hill and Frank Little died for? Are we still the I. W. W.? “Of course,” gravely replied B. “We are and eternally will be I. W. W. Wobbly etiquette never concedes any- thing, I swear it to you, to the High Priest Sandgren. You say you know not what. But it is all very simple. Listen! Once upon a time, there lived (according to the story told me in my infancy) not far from my birthplace in Russia, a youth by the name of Atanasic Kyrilovitch Makharof. This Makharof was of bad head, as happens with the youth of all lands. He launched himself into all the vices with as great a zest as later he plunged into remorse for them. In time, he studied Kropotkin and spoke of giving his life to his fellow-men. “At the end he became completely deranged, crazy. Crazy enough to lock up. And he was locked up, really, in a sanitarium at Simferopol. All he did was—what do you think! He imagined himself turned into a rooster! He ran thru the garden of the asylum looking for worms, and when he found one he seized it with his toes, that he be lieved to be claws, and carried it to his mouth, which he believed was a beak; and cried out with all his might — ‘Cock-a-doodle-doo, cock-a-doodle- doo.’ The insane have peculiar abil- ities; you or I would have great dif- ficulty in raising our toes to our mouths; but he, this deranged chap, did it easily from the first. Poor Makharof was of a family of ‘tchinovniks’—officials—very rich, and respected by all the district. He was an only son, and his condition saddened his father and mother. His father went to visit the asylum for a week and wept bitterly at always see- ing his son in the same state of mind. He said to the doctor: “Doctor, is there no way of help- ing it? I would give anything I have for his health, and it would be a cure that would cause you to be honored all consented to attempt the cure. scratched the sand with his foot per- fectly; he found, or pretended to find something to raise to his lips; leaped upon a chair, from there to a table, waving his arms as if they were wings, and screaming—‘Cock-a-doodle- doo.’ Makharof was astonished, and —at first—much pleased. There were now two roosters in the establishment and as there were no hens there was no reason for combat. He afid his col- league observed the best of ‘chicken manners’ and sang triumphal songs. In fact, each attaining the ides of the species ‘rooster.’ Who Believed Himself a Rooster over the world.’ “At last the doctor replied: “There is only one way. And I do not know if it would suweceed, but we can try. someone who may be able to act as much like a rooster as he does.’ It is necessary tho, to find “‘T don’t see,’ replied the father, what good would come of that.’ “‘T told you that all we are able to do is to experiment, responded the doctor.’ “At last they found an acrobat who He he they perfected themselves, “However, by reason of seeing his companion doing the same as he did, and surpassing him, Makharof became a bit weary. “‘Listen,’ he said to the acrobat, ‘suppose we no longer climb on the table. We are roosters. Certainly, I believe that we are roosters. I would not concede the least doubt in that matter. table!’ But let us not climb on the “Some days later he burst out: “Why should we go looking for worms? That is no good! ... Between ourselves, that is no good! Let us only pretend it. Look! See how I do it! See how I raise my foot. How I open my beak! Cock-a-doodle-doo! Cock-a-doo- adle-doo! Raise your foot! We do that only. Cock-a-doodle-doo!’ “*Cock-a-doodle-doo,’ responded the acrobat. “Sometime even proposed: “ee afterward, Makharof “We are roosters; nothing is more certain. If anyone tried to assert we are not, I would bury my spurs in his face. But, old friend, if you only knew how idiotic you look when you raise your foot! ... Let us only crow— Cock-a-doodle-doo!’ “*Cock-a-doodle-doo!’ responded the acrobat. “At last Makharof arrived at this: “‘Cock-a-loodle-doo is absolutely useless! . Let us have no more cock-a-doodle-doo! This does not stop us from being roosters. Nothing is more certain. We are and shall always continue to be roosters! ... Never will we say anything different to any- one ... But, do you know, I feel the desire for going out to walk around the city.’ “Thus it was that Makharof finally left the asylum. He married arid be- came a man the same as any other. Sometimes he met the acrobat. Then he would say to him, almost without moving his lips: “*But we are yet, and always, roost- ers.’ “However, by reason of always liv- ing as a man and not as a rooster he ended by completely forgetting that he was a rooster. Or well it was that he recalled it only in dreams, at night, when he was in bed—all of a sudder he would say—‘Cock-a-doodle-doo!’ “And his wife, startled into wake- fulness, would ask:— “What ails you?’ “Always he replied—Nothing. Don’t worry yourself.’ P “He died, finally, with the reputa- tion of a good citizen, of peaceful hab- its and conventional manners. B stopped and looked thoughtfully at a bird flying over the wall. “Well, now,” said A, after a pause, “what is the meaning of this fable, fellow-worker?” “We are roosters,” affirmed B- “We are always roosters; or, if you wish, I. W. W., revolutionary industrial unionists, advocates of Education, Or- ganization and Emancipation. Never will we say anything different to any one.” But just then the bugle blew—“re- call”—and both fell in line to shuffle into their cells. (Finis.) H. G. LEAVENWORTH. The Philistine Discourseth (Continued from page 2) talism has destroyed the English na- tional docks, has made it impossible to exploit the coal mines in a rational manner, etc. Ilyitch was familiar with the language of facts and figures. “T confess,” concludes Mr. Wells un- expectedly, “it was very difficult for me to argue against him.” What does this mean? Is it the beginning of the capitulation of evolutionary Collecti- vism before the logic of Marxism? No, no, “abandon all hope!” This phrase, which at the first glance ap- pears unexpected, does not occur by mere chance; it forms part of the system, it bears a strictly outspoken Fabian, evolutionary, pedagogic char- acter. It is expressed with an eye to the English capitalists, bankers, lords and their ministers. Wells says to them: “Just see, you behave so badly, so destructively, so egotistical- ly, that in my discussion with the Kremlin Dreamer I found it difficult to defend the principles of my evo- lutionary Collectivism. Listen to rea- son, take every week a Fabian bath, become civilized, proceed along the path of progress.” Thus the devout confession of Wells is not the. begin- ning of self-criticism, but merely the continuation of the educational work on this same capitalist society which has emerged from the imperialist wan and the peace of Versailles—perfect- ed, moralized and Fabianized. It is not without a feeling of bene- volent patronage that Wells remarks concerning Lenin: “His faith in his cause is unbounded.” There is no need the conversation Lenin had with Wells. It was quite otherwise when he spoke with English workers who came to him. He fraternized with them in the most hearty manner. He at once learned and taught. But with Wells the conversation, by reason of its very nature, had a half enforced diplomatic character. “Our conversation ended without definite result,” concludes the author. In other words the encoun- ter between evolutionary Collectivism and Marxism ended this time in noth- ing. Wells took his departure for England and Lenin remained in the Kremlin. Wells wrote a_ series of choice articles for the consumption of the bourgeois public and Lenin, shaking his head, repeated: “There goes a real petty bourgeois! Good gracious, what a Philistine!” But, one may ask, why on earth have I, almost four years afterwards, reverted to such a trifling article by Wells. The fact that his article has been reproduced in one of the books devoted to the death of Lenin is no sufficient justification. It is likewise no sufficient justification that these lines were written by me in Sukhum while undergoing a cure there. But I have more serious reasons. In Eng- land at the present moment the party of Mr. Wells is in power, led by illus- trious representatives of evolutionary Collectivism. And it seems to me—I think not without reason— that the lines written by Wells concerning Len- in reveal to us better than many other things, the soul of the leading strata of the English Labor Party; taken as a whole Wells is ndt the worst of the bunch. How hopelessly behind the times these people are, how burdened with the heavy leaden weight of bour- gois prejudices! Their arrogance— the belated reflex of the great his- torical role of the English bourgeoisie nations, into new ideological pheno- mena, into the historical process which is sweeping over their heads. Narrow-minded followers of routine, empiricists wearing the blinkers of bourgeois public opinion, they carry themselves and their prejudices into the whole world and are careful not to notice anything around them but only their own persons. Lenin had lived in all the countries of Europe; had made himself master of foreign languages; had read, studied, and listened; made himself familiar with things, compared and generalized. Standing at the head of a great revolu- tionary country, he omitted no occa- sion to learn conscientiously and care- fully, to ask for information and news. He followed unweariedly the life of the whole world. He both read and spoke German, French and English with ease and also read Italian. In the last years of his life, when over- burdened with work, he surreptitious- ly, during thé sittings of the Political Bureau, studied a Czechish grammar in order to come into first-hand con- tact with the workers’ movement of Czecho - Slovakia; we sometimes “caught” him at this when he, not without some slight embarrassment, passed it off with a laugh and apolo- gized . . . And there on the other hand we have Mr. Wells, incarnating that kind of pseudo-educated, narrow- minded petty bourgeois, who look around with the intention of seeing nothing and who consider that they have nothing to learn as they feel quite assured with their inherited stock of prejudices, And Mr. Mac- Donald, who represents a more solid and sober puritan variety of the same type, pacifies bourgeois public opin- ion: We have fought against Mos- cow and we have Vanquished Mos- cow. They have vanquished Moscow? These are indeed wretched “little men” no matter how tall physically! Today even after all that has trans- pired, they know nothing whatever about their own tomorrow. Liberal and conservative business people with- out the least difficulty bait traps for these “evolutionary” socialist pe- dants who are now in office, com- promise them and intentionally pre- pare their downfali—not only as min- isters, but also as politicians. Simul- taneously—altho far less intentional- ly—they prepare for the coming to power of the English Marxists. Yes, indeed, of the Marxists, “of the weary fanatics of the class struggle.” For the English social revolution will also proceed in accordance with the laws laid down by Marx. Mr. Wells, with his characteristic, pudding-heavy wit, once threatened to take a pair of scissors and trim the “doctrinaire” hair and beard of Marx and to render him English and re- pectable: to Fabianize him. But nothing has come of this and nothing ever will come of it. Marx will re- main Marx just as Lenin has re- mained Lenin after Wells had sub- jected him for an hour to the tor- menting effects of a blunt razor. And we venture to predict in the not dis- tant future, there will be erected in London, in Trafalgar Square for ex- umple, two statues standing side by side: Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin. The English proletarians wif say to their children: “What a good job it is that no little pygmies of the Labor Party succeeded in trimming the hair or shaving the beard of these two giants!” In anticipation of these days, which I myself will endeavor to see, I close my eyes for a moment and distinctly see before me the figure of Lenin in his armchair, the same chair in which Wells saw him, and I hear—on the day followitig or perhaps on the day of the conversation with Wells—the words, accompanied by a heavy gasp: “Ugh! $What a petty bourgeois! What a Philistine!”