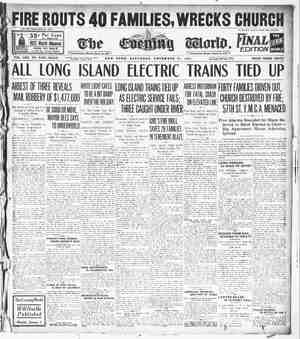

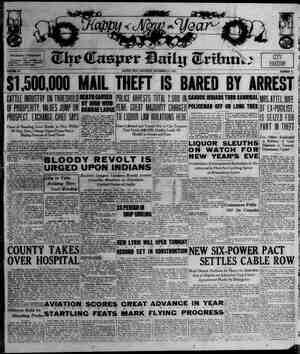

Casper Daily Tribune Newspaper, December 31, 1921, Page 9

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

for whatever small privacy between American sip. At this season of the year, In our towns of moderate size and ambition, where apartment houses have not yet condensed and at the same time Sequestered the population, one may trouble to sit for an hour or so, daily, upon the top of a high board fence at about the middle cf a block. Of course an adult who followed such a course would be thought pe- culiar; no doubt he would be subject to undesirable comment, and presently might be called upon to parry severe if, Indeed, not hostile inquiries; but boys ars considered so inexplicable that they have gathered for them- selves any privileges denied their parents and elders; and a boy can do such a thing as this te his full content, without anybody’s thinking about it at all. So it was that Herbert Dlings- worth Atwater, Jr, aged thirteen and a few months, sat for a considerable time upon such a fence, after school hours, every afternoon of the last week in October; end.only one person par- ticularly observed him or was stimu- lated to any mental activity by his procedure, Even at that, this person was affected only because she was: Herbert's relative, and of an age sym- pathetic to his—and of a sex antipa- thetic. In spite of the fact that Herbert Il- Ungsworth Atwater, Jr., thus seriously Gisporting himself on his father’s back fence, attracted only this audience of one (and she hostile at a rather dis- tant window) his behavier really should have been considered piquant- ly interesting by anybody. After climb- ing to the top of the fence he would produce from interior pockets a smal! memorandum book and a pencil; sel- dom putting these implements to Im- mediate use, His expression was gravely alert, his manner more than ©; yet nobody could have \ fafled to comprehend that he was en- _joying himself, especially when hia at iat" Becane tense—as Fig a it certainly did. Then he would rise, bal- ancing himself at adroit ease, his fect aligned one before the other on the Anner rail, a foot below the top of the boards, and with eyes dramatically shielded beneath a scoutish palm, he ‘would gaze sternly in the direction of Bome object or motion which had at- tracted his attention; and.then, having satiafied himself of som: or other, he would sit again and decisively en- ter a note in his memerandum book. He was not alwayy alone; he was frequently joined by a friend, male, and, though shorter than Herbert, quite as old; and this companion was inspired, it seemed, by motives pre- cisely similar to-those from which sprang Herbert's own actions. Like Herbert, he would sit upon the top of the high fence, usually at a little dis- tance from him; like Herbert he would rise at intervals, for the better study of something this side of the horizon; then, also concluding like Herbert, he would sit again and write firmly in a little notebook. And sel- dom in the history of the world have any sessions been invested by the par- ticlpants with so intentional an ap- pearance of importance. “That was what most injured their lone observer at the somewhat distant back window, upstairs at her own Place of residence; she found their im- Portance almost impossible to bear without screaming. Her provocation was great; the important importance of Herbert and his friend, impressive- ly maneuvering upon their fence, was 80 extreme as to be all too plainly vis- {ble across four intervening broad back yards; in fact, there was almost reason to suspect that the two per formers were aware of their audtence and even of her goaded condition; and that they sometimes deliberately in- creased the outrageousness of their importance because they knew she was watching them. And upon the Saturday of that week, when the note- book writers were upon the fence at intervals throughout the afternoon, Florence Atwater’s fascinated indigna- tion became vocal. “Vile things!” she said. Her mother, sewing beside another window ofthe room, looked up in- quiringly. 2 “What are, Florence?” “Cousin Herbert and that nasty lit- tle Henry Rooter.” - “Are you watching them again her mother asked. : “Yes, I am,” sald Florence, tartly. “Not because I care to, but merely to amuse myself at thelr expense.” Mrs, Atwater murmured Geprecat- 4 ingly, “Couldn't you find some other way to amuse yourself, Florence?” “T don’t call this amusement,” the inconsistent girl responded, not: with- out chagrin. “Think I'd spend all my days sterin’ at Herbert. Ulingsworth, SSE Yao! A Ape ee oe iW I table “Why do you ‘spend all your days’ watching them? You don't seem able to keep away from the window, and {t appears to make you Irritable. I should think {f they wouldn't let yon play with them you'd be too proud—" “Well,” asid Fiorence, “I got to use some when you accuse me ily Ht 5 | § H z i FI ga if ii wee i Te 3 tm any paper with such a crazy name and I wouldn't tell ‘em any news shoes I got on 'em!" “But why wouldn't they let you be expression of wantin’ to ‘play’ with those two vile | 0n the paper?” her mother insisted. things! My goodness mercy, mama, I don't want to ‘play’ with ’em! more than four years old, I guess; though you don't ever seem willing to give me credit for it J don’t haf to ‘play’ all the time, mama; end, any- way. Herbert and that nasty lttle Henry Rooter aren't playing, either.” “Aren't they?" Mrs. Atwater in- quired.” “I thought the other day you said you wanted them to let you play at being a newspaper reporter, or edi- tor, or something like that, with them, and they were rude and told you to go away. Wasn't that it?” Florence sighed. “No, mama, cert‘nly wasn’t.” “They weren't rude to you?” “Yes, they cert’nly were!” “Well, then—” “Mama, can't you understand?” Florence ‘turned from the window to beseech Mrs. Atwater’s concentration upon the matter. “It isn't ‘playing!’ I didn't want to ‘play’ being a report- er; they ain't ‘playing’—" “Aren't playing, Florenge.” “Yes'm. They're not: got a real printing press; Uncle Jo seph gave It to him, It's a real one, mama, can’t you understand?” * “Til try," sald Mrs. Atwater. “You mustn't get so excited about It, Flor ence.’ “I'm not!” Florence turned rehe- mently, “I guess it'd take more than those two vile things and their old printin’ press to get me excited! 1 don't care what they Go; It’s far less than nothing to me! All I wish is they'd fall off the fence and break their vile ole necks!” “With this manifestation of tmper- sonal calmness, she’ turned again to the window; but her mother protest- ed. “Do find something else to amuse you, Florence; and quit watching those foolish boys; you mustn't let them upset you so by their playing.” Florence moaned. “They don't ‘up- set’ me, mama! They have no effect on me by the slightest degree! And I told you, mama, they're not ‘playing.’” “Then what are they doing?” “Well, they're having a newspaper. They got the printing press and an Office In Herbert's ole stable, and ev- erything. ‘They got somebody to give ‘em some ole banisters and a railing from @ house that was torn down somewheres, and then they got it stuck up in the stable loft, so it runs across with a kind of a gate in the middle of these banisters, and on one side !s the printing press, and. the other side they got a desk from that nasty little Henry Rooter’s mother’s attic; and a ind some chairs, and a map on the i; and tha thelr newspaper office, They go-out-and look for what's the news, and write it down In ink; and then they go through the gate to the other side of the ralling where the printing press is, and print it for their newspaper,” “But what do they do on the fence 80 much?” “That's where they go to watch what the news Is,” Florence explained morosely, “They think they're so grand, sittin’ up there, pokin’ around. They go other places, too; and they ask people, That's all they said 1 it Herbert's became strongly intensified. “They ed if I knew anything, some- times, if they happen to think of It! I Just respectf'ly told ‘em I'd decline to wipe my oldest shoes on ’em to save their yes!” 2 Mrs. Atwater sighed. “You mustn't use such expressions, Florence.” “I don't see why not,” the daughter objected. “They're a Jot more refined gen the expressions they used on me!” “Then I'm very glad you didn’t play with them.” . But at this, Florence once more gave way to filial despair, you just can't see through anything! T've sald anyhow fifty times they ain't —aren't playing! They're getting up a Teal newspaper, and people buy it, and everything. They have been all over this part of town and got every aunt and uncle they have, besides their own fathers and mothers, and some people in the nelghborhood, and Kitty Silver and two or three other colored people besides, that work for families they know. They’re going to charge twenty-five cents a year, collect-in-ad- vance beciuse they want the money first; and even papa gave ’em a quar- ter last night; he told me so,” Tm peal | Upon this Florence became analyti- “Just so’s they could act so im- portant!" And she addded, as a con- pcre? “They ought to be arrest- Mra, Atwater murmured absently, but forbore to press her inquiry; and Florence was silent, in a brooding mood. The journalists upon the fence had disappeared from view, during the conversation with her mother; and Presently she sighed and quietly left the room. She went to her own apart- ment, where, at a small and rather battered little white desk, after a pe riod of earnest reverie, she took up @ pen, wet the point in purple ink, and without any great effort or any criti- cal delayings, produced a poem. It was, in a sense, an original poem; though, like the greater number of a! literary offerings, it was so strongly inspirational that the source of its inspiration might easily become mani- fest to a cold-blooded reader. Never- theless, to the poetess herself, as she explained later in good faith, the words Just seeined to come to her—doubtless with elther genius or some form of Miracle involved; for sources of in- spiration are seldom recognized by in- spired writers themselves. She had not long ago been party to a musical Sunday afternoon at her great-uncle Joseph Atwater's house where Mr. Clairdyce, that amiable and robust baritone, sang some of his songs over and over again, as. long as. the re quests for them held out. Florence’s poem may have begun to coagulate within her then, THE ORGANEST By Florence Atwater ‘ The organest was seated at hia organ ti “ in a church, In some beautiful woods of maple and birch, very. weery while he played upon 3 great organest and always Played with ease, When the soul is weary, And the wind ts dreary, I would like to be an Organest seated a1! day at the organ, Whether my name might be Fairchild or Morgan, I would play music like a vast amen, ‘The way it sounds in a church of men, Florence read her poem over seven or eight times, the deepening pleasure of her expression being evidence that cepetition failed to denature this work, but, on the contrary, enhanced an ap- preciative surprise at its singular mer- {t, Finally she folded the sheet of paper with a delicate carefulness un- usual to her, and placed it in her skirt pocket. ‘TMen she went down- stairs and out into the back yard. With thoughtful and determined eyes she obliqued her gaze over the in- tervening fences to the repellent sky- Une formed by the too-simple profile of her cousin Herbert's father’s sta- ble. Her next action was straight- forward and anything but prudish; she climbed the high board fences, one af- ter the other, until she came to a pause at the top of that whereon the two journalists had lately made them- selves so odiously impressive. Before her, if she had but taken note of them, were a lesson tn history and the markings of a profound transi- tion in human evolution. Beside the old frame stable was a little brick garage, obviously put to the daily use intended by its designer. Quite as ob- viously the stable was obsolete; any- body would have known from !ts out- side that there was no horse within it, Here, visible, was the end of the pastoral age, it might be called, from the Heidelberg jawbone to Mar- cont, The new age begins with ma- chiles that do away with laboring ani- mals and will proceed presently to machines doing away with laboring men, although it is true that cows may remain in vogue for some time. In spite of the fact.that they are already milked by electricity, the milk Itself must yet be constructed by the cow. All this was lost upon Florence. She sat upon the fence, her gaze un- favorably, though wistfully, fixed upon a Bign of uo special esthetic merit above the stable door: THE NORTH END DAILY ORIOLD. WNERS ATWATER & ROOTER 0’ AND PROPREITORS. SUBS' CRIBE NOW % CENTS. The inconsistency of the word “daily” did not trouble Florence; more- over she had found no fault with “Oriole” uniil the “Owners and Pro- 4 eS Ve aa ee Cage oat —— praitere* RAC é¥plelned to her tn the plainest terms known to their vocabu- laries that she wse excluded from the enterprise, hes, indeed, she had been reciprocally explicit in regard, not only to them and certain personal characteristics of theirs which she Pointed out as fundamental, but in re- gard to any newspaper which should deliberately call itself an “Oriole.” ‘The partners remained superior in manner, though unable to conceal a natural resentment; they had adopted “Oriole,” not out of sentiment for the distant city of Baltimore, nor, indeed, on account of any ornithologic inter- est of their own, but as a relic from an abandoned club, or secret society, which they hed@ previously contem- plated forming, its members ta be called “The Orioles” for no reason whatever, The two friends had talked of their plan at many meetings throughout the summer, and when Her- bert’s great-uncle, Mr. Joseph At- water, made his nephew the uner pected present of a printing press, and & hewspaper consequently took the place of the club, Herbert and Henry still entertained an affection for their former scheme and decided to perpet- uate the nama They were the more sensitive to attack upon It by an tg- norant outsider and girl like Florence, and her chance of ingratiating her- self with them, if that could be now her tntention, was not promising. It would be tmaccurate to speak of her as hoping to placate them, how- ever; her mood was inscrutable. She descended from the fence with pro- nounced inelegance, and, approaching the old double doors of the “carriage- house,” which were open, paused to listen. Sounds from above assured her that the editors were editing—or at least that they could be found at thelr place of business. Therefore, she ascended the cobwebby stairway to the loft, and made her appearance In the printing room of the North End Daily Oriole. Herbert, frowning with the burden of composition, sat at a table beyond the official railing, and his partner was engaged at the press, painfully setting Oke ror several inoats Nad oamed Sate sthorwtes than as nasty lttle Henry Rooter,” was of strangely clean and smooth fair-haired appearance, for his age. She looked him over. His profile was of a symmctry le had not himself yet begun to sppre- ciate; his dress was scrupulous and modi: and though he was short nothing outward about him explained the more sinister of Florence's two adjectives. Yet she had true occasion for it, because on the day before she began its long observance he had made her uneasy lest an orange seed sh: bad swallowed should take root and grow up within her to a size inevi- tably fatal. Then, with her cousin Herbert's stern assistance, Florence had realized that her gullibility was Isn't any child's p haven't got tHe face to stand mere and clalza you got a right to go in a Bewspaper building and sey you got a right there when everybody telis you to stay outside of it, I guess!" “Oh, Daven’t I?” “No, you haven’t—I!" Mr, Rooter maintained bitterly. “You just walk downtown and go In one of the news- paper buildings down there and tell ‘em you got a right to stay there all Gay long when they tell you to get out o’ there! Just try it! That's ali I ask!" Florence uttered a cry of derision. “And pray, whoever told you I was bound to de everything you ask me to, Mister Henry Rooter? And she con- cluded by reverting to that hostile impulse, 60 ancient, which tn despair of touching an antagonist effectively, reflects upon his ancestors, “If you got anything you want to ask, you go ask your grandmotber!” “Tere!” Herbert sprang to his feet, outraged. “You try and Debave Ifke a lady!" “Who'll make me?” she {nquired. “You got to behave like a lady as long a you're in our newspaper build- ing, anyway,” Herbert said ominously. “If you expect to come up here after you been told five dozen times to keep ont—” “For heaven's sakes!" his partner interposed. “When we goin’ to get our newspaper work done? She's your cousin; I should think you could get her out!" “Well, Tm goin’ to, ain't I?” Her- bert protested plaintively, “I expect to get her out, don't I?” “Oh, you do?" Miss Atwater in- quired, with severe mockery. “Pray, how do you expect to accomplish it, Dray?" Herbert looked desperate, but was unable to form a reply consistent with some rules of etiquette and gallantry which he had begun to observe during the past year or so. “Now, see here, Florence,” he said. * “You're old enough to know when people tell you to keep out of a place, why, {t means they want you to stay away from there.” Florence remained cold to this rea- soning. “Oh, poot!” she said, “Now, look here!” her consin ‘re- monstrated, and went on with his ar- gument. “We got our newspaper work to do, and you ought to have sense enough to know newspaper work like this newspaper work we got on our hands here {sn't—well, it ain't any child's play.” His partner appeared to ayprove of the expression, for he nodded severely and then used it himself. “No, you bet It isn't any child's play!” he said. “No, sir, Henry Rooter again agreed. “Newspaper work like this jay at alll” “Tt isn't any child's play, Florence,” said Herbert. “It ain't any child's play at all, Florence, If ft was just child's play or something like that, why it wouldn’t matter so much your A TALE of pure delight; one of the great Ameri- can writer’s immortal “kid” stories. \ Fit to “Too io along with “Penrod,” “Seventeen” or tle Julia;” in fact, it is woven about the same interesting characters as the latter. “The Oriole” deals with “thirteen,” that transition age between childhood and youth when one never knows what the young human offspring will be up to next. It is the age when tion takes the most unexpected turns and fancy plays the qu In this narrative Mr. T: his genius for character, ‘on brings to bear all tuations and humor. Every line is either a laugh or a study in the delect- able ways unboun joy. not to be expected In anybody over seven years old, after which age such legends are supposed to be encoun- tered with the derision of experienced people. Her fastidiousiess aroused, she de- cided that Henry Rooter had no busi- ness to be talking. about what would happen to her insides, anyhow; and so informed him at thelr next meeting, adding an explanation which absolute- ly proved him to be no gentleman. And her gpinion of him was still per- fectly plain in her expression as she made her present ‘IntruSion upon his working hours. He seemed to re elprocate, “Here! Didn't I and Herbert tell you to keep out o’ here?’ he demand- ed, even before Florence had devel- oped the slightest form of greeting. “Look at her, Herbert! She's back again |” “You get out o’ here, Florence,” said Herbert, abandoning his task with a look of pain. “How often we haf to tell you we don’t want you around here when we're in our office like this?” “Bur beeven’s sake!" Henry Rooter thought fit to add. “Can't you quit running up and down our office stairs once In a while, long enough for us to get our newspaper work done? Can't you give us a little peace?” The pinkiness of Florence's alter ing cotaplexion was justified; she had not been near their old office for four days. She stated the fact with heat, adding: “And I only came then be- enuse I knew somebody ought to see that this stable isn’t ruined. It's my own uncle and aunt's stable; and I got as much right here as anybody.” “You have not!” Henry Rooter pro- tested hotly. ‘This isn't, elther, your ole aunt and uncle’s stable.” “Tt isn’t!” “No, it is not! This isn’t anybody's stable. It's my and Herbert's news- Paper building, and I guess _you Pi a VC IE aes gma ws SACS of the young; the whole is a work of always pokin up here, and—* “Well,” the partner interrupted, ju- dictally, “We wouldn't want her around, even if {t was cnild's play.” “No, we wouldn't; that's so,” Her bert agreed. “We wouldn't want you arennd, any- how, Florence.” Here his tone be- came more plaintive, “So, for mercy’s sakes, can't you go on home and give us a little rest?) What you want, any- how?" “Well, I guess it’s about time you was askin’ me that,” she said, not un- reasonably. “If you'd asked me that in the first place, instead of actin’ like you'd never been taught anything, and was only fit to associate with hood- lums, perhaps my time {s of some value, myself!” ‘The lack of rhetorical cohesion was largely counteracted by the strong expressiveness of tone and manner; at all events, Florence made perfectly clear her position as a person of worth, dealing with the lowest of all her inferfors, She went on, not paus- ing: “I thought, being as I was related to you, and all the family and everybody else goin’ to haf to read your ole newspaper, anyway it'd be a good thing if what was printed in {t wasn't all a diegrace to the family, because the name of our family’s got mixed up with this newspaper; so here!” Thus speaking, she took the poem from her pocket and with dignity held {t forth to her cousin, “What's that?” Herbert inquired, not moving a hart. He was but an ama- teur, yet already enough of an editer to have his suspicions. “It’s a poem,” Florence sald. “I don't know whether I exackly ought to have it in your ole newspaper or not, but on account of the family's sake I guess 1 better. Here, take it,’ Herbert at once withdrew a few steps, placing his hands behind him. “Listen, here,” he said, “you think we Ka a aie (0 i= =a Zs eS ar ee ae ars LOT ZS SS Siza So = z aa =a RS SAN RRR SS eZ S We ee BOOTH TARKINGTON ‘This eminent hoosier has. for years been acclaimed one of the greatest of American authors, “The Turmoll,” “Seventeen” and the Penrod stories, are only a few of the many from his pen that have made fame, popularity and wealth for him. In 1919 his work, “The Magnificent Ambersons,” won the Pulitzer prize for the best story pub- Ushed during the year, “presenting the wholesome atmosphere of American life and the hig! standard of American manners manhood.” His tale, “The Oriole.” which you will ha opportunity to follow {n serial form In this paper, is one of those fas- cinating, extremely humorous depic- tions of child life which best Ulustrate Dis talents, got tinié tO read a lot & writin’ tn your ole handwritio' that nobody can read anyhow, and then go to work and toll and moll to print it on the printin’ press? I guess we got work enough printin’ what we wrote for our news- baper our own eelves! My goodness, Florence, I told you this isn't any child's play!” : Florence appeared to be somewhat baffied. “Well,” she sald. “Well, you better, put this poem in your ole news- paper If you want to have anyhow one thing In {t that won't make everybody sick that reads !t.” “I won't do it!" Herbert sald, more firmly. ‘ “What you take us for?” his partner added, convincingly, “All right, then,” Florence respond- ed, with apparent decisiveness, “T'll go back and tell Uncle Joseph and he'll take this printing press back.” “He will not take It back. I already did tell him how you keep pokin’ around tryin’ to run everything, and we just worried our lifes out tryin’ to keep you away. He sald he bet {t was a hard job; that’s what Uncle Joseph said. So go on, tell him anything you want to, You don’t get yor ole poem in-our newspaper!” “Not if she lived to be two hundred years oldi" Henry Rooter added. Then he had afterthought, “Not unless she pays for tt." “How do you mean?” Herbert asked, puzzled, Henry's brow had become corrugat- ed with no little professions! impres- sive . “You know what we were talkin’ about this morning,” he sald. “How the right way to run our news- paper, we ought to have some adver- tisements Ia {t and everything. Well, we want money, don’t we? We could put this poem in our newspaper Ike an advertisement; that Is, if Florence bas got any money, we could.” Herbert frowned. “If her ole poem isn't too long. I guess we could. Here, let's ‘see {t, Florence.” And, taking the sheet of paper in his hand, he studied the dimensions of the poem, though without paining himself to read it. “Well, I guess, maybe-we can do it,” he said, “How much ought we to charge her?” ‘This question plunged Henry Rooter into a state of calculation, while Flor- ence observed him with velled anx!- ety; but after a time he looked up, his row showing continued strain. “Do you keep a bank, Florence—for nickels and dimes and maybe quar ters, you know?" he inquired. It was her cousin who tmpulsively replied for her. “No, she don't,” he sald. “Not since I was about seven years oli!" Florence added sharply, though with dignity. “Do you still make mud ples in your back yard, pray?” “Now, see here!” Henry objected. “Try and be a lady anyway for a few minutes, can't you? I got to figure out how much we got to charge ren for your ole poem, don’t I?" “Well, then,” Florence returned, “you better ask me somep’m about that, hadn't you?” “Well,” said Henry Rooter, “have you got any money at home?’ “No, I haven't.” | “Hrve you got any money with you?” “Yes, I hare.” “How much ts It? “I won't tell you.” Henry frowned. “I guess we onght to make her pay about two dollars and | a half,” he said, turning to his part- ner. Herbert felt deferential; it seemed to him that he hnd formed a business association with a genins, and for a moment he was darzied; then he re- membered Florence's financial capac- 2 pone SSE ol Sh — : US? It’s a Scream! THE ORIOLE By Booth Tarkington . Atwater and Henry ities, always well known fo him, and he looked depressed. Florence, her- self, looked indignant. “Two dollars and a half!" she cried. “Why, I could buy this whole place for two dollars and a half, printing press, rafling, and all—yes, and you thrown in, Mister Henry Rooter!* “See here, Florence,” Henry said earnestly, aven't you got two dol- Jars and a halt?” “Of course she hasn't!” his partner assured him, “She never had two dollars and a half in her life!" “Well, then,” said Henry gloomily, “what we goin’ to do about it? How much you think we ought to charge her?” Herbert's expression became non- committal, “Just let me think a min- ute,” he sald; and with his hand to his brow stepped behind the unsus- pictous Florence. “I got to think,” he murmured; then with the straightforwardness of his age, he suddenly seized his damsel cousin from the rear and held her in a tight but far from affectionate em- brace, pinioning her arms, She shrieked, “Murder!” and “Let me go!” and “Help! Hay-yuipi” “Look in her pocket," Herbert shouted. “She keeps her money in her skirt pocket when she’s got any. It's on the left side of her, Don't let her kick you! Look out!" “I got it!” sald the dexterous Henry, retreating and exhibiting coins, “It’s one dime and two nickele—twenty cents. Has she got any more pock- ets “No, I haven't!" Florence fiercely informed him, as Herbert released her, “And I guess you better hand that money back {f you don't want to be arrested for stealing!” Henry was unmoved. “Twenty cents,” he said calculatingly, “Well, all right; tt ‘sn't much, but you can have your poem in our newspaper for twenty cents, Florence. If you don't want to pay that much, why take your ole twenty cents and go on away!" “Yes," sald Herbert. “That's as cheap as we'll do it, Florence. Take it or leave { “Tuke it or leave it,” Henry Rooter agreed. “That's the way to talk to her; take it, or leave ft, Florence. If you don't take it you got to leave !t.” Florence was indignant, but de cided to take it. “All'right,” she said coldly. “I wouldn't pay another cent if I died for !t.” “Well, you haven’t got another cent, so that's all right,” Mr. Rooter re- marked; and he honorably extended fn open palm, supporting the coins, toward his partner. “Hera Herbert; you can have the dime, or the two nickels, whichever you rather have It makes no difference to me; Td as soon have one as the other.” Herbert took the two nickels, and turned to Florence. “See here, Flor ence,” he said, in a tone of strong complaint. “This business is all done and paid for now. What yon want to hang around here any more for?” “Yes, Florence,” his partner faith- fully seconded him, at once. “We haven't got any more time to waste around here today, and so what you want to stand around In the way and everything for? You ought to know yourself we don’t want you.” “[m not In the way,” sald Florence hotly. “Whose way am I in?” “Well, anyhow, if you don’t go,” Herbert informed her, “we'll carry you downstairs and lock you out.” To be Continued) er The Blenheim spantel got its na from Blenheim palace, where dog first gained popularity time of the great Duke of borough. the Marl- k= ~ ee eT aS ws S= SS awee ee at PR aan) —