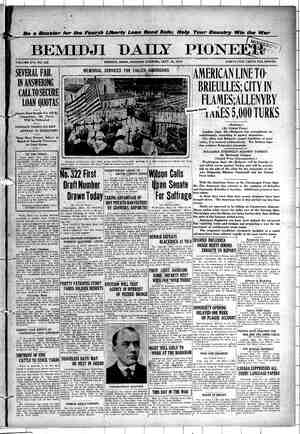

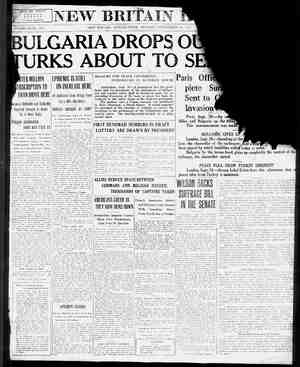

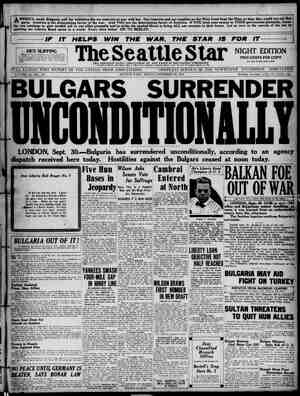

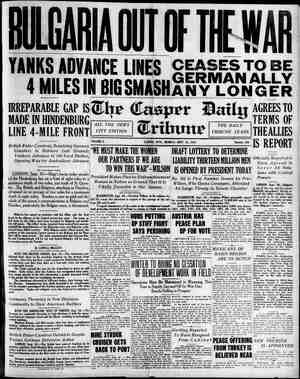

Casper Daily Tribune Newspaper, September 30, 1918, Page 5

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

mm aa) pes Ss MONDAY, SEPT. 30, 1918 EX-GUNNER AND CHIER PETT NAVY. . MEMBER, OF THE FOREIGN LEGION OF FRANCE CAPTAIN GUN TURRET, FRENCH BATTLESHIP CASSARD —> ‘WINNER OF THE CROIX DE GUERRE { Ceayrids 1918, by Rely and Brinon Ca, Thecugh Special Arrangement Weh the George Mathew Adama Servicn, CHAPTER |. In the American Navy. My father was a staman, so, nat- urally, all my life I heard a great deal about ships and the sea. Even when I was a little boy, in Walston, Pa., I thought about them a whole lot and wanted to be a sailor—especially a sailor in the U. S. navy. You might say I was brought up on the water. When I was twelve years old I went to sea as cabin boy on the whaler ‘Therifus, out of Boston, She was an old square-rigged sailing ship, bulit more for work than for speed. We were out four months on my first cruise, and got knocked around a lot, especially in a storm on the Newfound-: land Banks, where we lost our instru- ments, and had a hard time navigat- ing the ship. Whaling crews ‘work on_ shares and during the two years I was on.the Therifus my shares amounted to fourteen hundred dollars. Then I shipped as first-class helms-' man on the British tramp Southern- down, a twin-screw steamer out of Liverpool. Many people are surpri: that a fourteen-year-old boy should be helmsman on an ocean-going craft, .but all over the world you will see young lads doing their trick at the wheel. I was on the Southerndown two years and in that time visited > most of the important ports of Bu- rope. There is nothing like’a tramp steamer if you want to see the world. The Southerndown is the vessel that, in the fall of 1917, sighted a German U-boat‘rigged up like a sailing ship. Although I liked visiting the foreign ports, I got tired of the Southerndown after a while and af the end of a voy- age which landed me in New York I decided to get into the United States navy. After laying around for a week or two I enlisted and was assigned to duty as a second-class fireman. People have said they thought I was pretty small to be ,a fireman; they have the idea that firemen must be big men, Well, I am 6 feet 74% inches in height, and when I was sixteen I was just as tall as I am now and weighed 168 pounds. I was a whole lot husk- Gunner Depew. fer then, too, for that was before my introduction to kultur in German pris- on camps, and life there is not exactly fattening—not exactly, I do not know why it is, but if you will notice the navy firemen—the lads with the red stripes around their left shoulders— you will find that almost all ef them arp small men. But they are a husky lot. Now, in the navy, they always haze 4 newcomer until he shows that he can take care of himself, and I got mine very soon after I went into Un- cle Sam’s service. I was washing my clothes in a bucket on the forecastle deck, and every garby (sailor) who came along would give me or the bucket a kick, and spill one or the both of us. Each time I would move to some other place, but I alw Scemed to be in somebody's way. F nally I saw a marine coming. I was howhere near him, but he hauled out of his course to come up to me and fave the bucket a boot that sent it twenty feet away, at the same time handing me a clout on the ear that Just about knocked me down, Now, 1 did not exactly know what a marine was, and this felow had so many Stripes on his sleeves that I thought he must be some sort of officer, so I Just stood by. There was a gold stripe (commissioned offiger) on the bridge snd I knew that if anything was Wrong he would cut in, so I kept look- ing up at him, but he stayed where he was, looking on, und never saying al Word, And all the time the marine kept slamming me about and telling me to get the hell out of there, | *inally I sald to myself, “I'M ‘get this ‘guy if it’s the brig for a month. So I planted him one in the kidneys and another in the mouth, and he went clean up against the rail. But he came back at me strong,and we were at it for some time. But when it was over the gold ecripe came down from the bridge and shook hands with me! After this they did not haze me much. This*was the beginning of a certain reputation that I had in the navy for fist-work, Later on I had a reputation for swimming, too. That first day they began calling me “Chink,” though I don’t know why, and it has been my nickname in the navy ever since, It is a curious thing, and I never could understand it, but garbies and marines never mix. The “marines are good men and great fighters, aboard and ashore, but we garbies never have a word'for them, nor they for us. On shore leave abroad we pal up with foreign garbies, even, but hardly ever with a marine. Of course they are with us strong in case we have a serap with a liberty party off some foreign ship-—they cannot keep out of a fight any more than we can—but after it is over they are on their way at once and we on ours, : There are lots of things like that in the navy that you cannot figure out the reason for, and I think it is be cause sailors change their ways so little. They do a great mang things in the navy because the navy always has done them, I kept strictly on the job as a fire man, but I wanted to get into the gun turrets. It was slow work for a long time. I had to serve as second-class fireman for four mouths, first-class for eight months and in the engine Toom as water-tender fer a year. Then, after serving cn the U. S. 8S. Des Moines as a gunloader, I was transferred to the Iowa and finally worked up to a gun-painter. After a time I got my C. P. Q. rating—chiet petty officer, first-clasg gunner. The various navies differ ;in many ways, but most sof the differences would not be noticed ty any one -but a sailor, Every sailor has a great deal of respect for the Swedes and Nar- wegians and Danes; they are born sailors and are very daring, but, of course, their navies are small. The Germans were always known as clean sailors; that is, as im our navy and the British, their vessels were ship- shape all the time, and were run as sweet as a clock, ‘There Is no use comparing the vari- | ous navies as to which is best; some are better at one thing and some at another. The British navy, of course, is the largest, and nobody will deny that at most things they are topnotch —least of all themselves; they admit it. But there i$ one place where the navy ef the United States has it all over every other navy on the seven seas, and that is gunnery. The Amer- ican navy has the best gunners in the world. And do not let anybody tell you different. CHAPTER II. | The War Breaks, After serving four years and three months in the U. 8. navy, I received an honorable discharge on April 14, 1914. I held the rank of chief petty officer, first-class gunner. It is not uncommon for garbies to lie around a while between enlistments—they like a vacation as much as anyone—and it was my intention to loaf for a few months before joining the navy again. After the war started, of course, I had heard more or less about the Ger- man atrocities in Belgium, and while { was greatly interested, I was doubt- tul at first as to the truth of the re- sorts, for I knew how news gets changed in passing from mouth to mouth, and I never was much of a hand to believe things until I saw them, anyway. Another thing that caused me to be interested in the war as the fact that my mother was born n Alsace. Her maiden name, Dier- veux, is well known in Alsace, I had ften visited my grandmother in St. Nazaire, France, and knew the coun- ry. So with France at war, it was 1ot strange that I should be even nore interested than many other sarbies. As I have said, I did not take much stock in the first reports of the Hun’s -xhibition of kultur, because Fritz 1s mown as a clean sailor, and I figured chat no real sailor would ever get nixed up.in such dirty work as they aid there was in Belgium. I figured | che soldiers were lil:e the sailors. But |{ found out I was wrong about both, One thing that opened my eyes a lolt was the trouble my mother had in settmg out of Hunover, where she vas when the war started, and back ‘o France. She always wore a lttle american flag and this both saved and i 5 ie . @ndangered her, Without it, th mans would have dotaenéa nae sh Frenchwoman, and with it, she was Sheered at and insulted time and again before she finally managed to fet over the border. She died about two months after she reached St. Na- zaire. Moreover, I heard the fate of my older brother, who had made his home in France with my grandmother, He had gone to the front at the outbreak of oP war with the infantry from St, Nazaire and had been killed two or three weeks afterwards. This made it a sort of personal matter. But what put the finishing touches to me were the stories a wounded Canadian Meutenaht told me some months) later in New Yori. He had been there and he knew. You could not help believing him; you can al- Ways tell it when a man has been there and knows, , There Was not much racket around New York, so I made up my mind all of a sudden to go dver and get some for myself. Believe me, I got enongh racket before I was through. Most of the really important things I have done have happened like that: I did them on the jump, you might say. Many pther Americans wanted a look, too; there were five thousand Amer- icans in the Canadian army at one time they say, : I would not claim that I went over there to save democracy, or anything like that. I never did like Germans, and I never met a Frenchman who was not kind to me, and what I heard about the way the Huns treated the Belgians made me sick, I used to get out of bed to go to an all-night picture show, I thought about it so much. But there was not much excitement about New York, and I figured the U. S. would not get into it for a while, anyway, so I just wanted to go over and see what it was like. That is why lots of us went, I think, There were five of us who went to Boston to ship for the other side: Sam Murray, Ed Brown, Tim Flynn, Mitchell and myself. Murray was an ex- garby—two hitches (enlistments), gun- pointer rating, and about thirty-five Years old. Brown was a Pennsylvania man about twenty-six years old, who had served two enlistments in the U. S. army and had quit with the rank of sergeant, Flynn and Mitchell were both ex-navy men. Mitchell was a noted boxer. Of the five of us, I am the only one who went in, got through and came out. Flynn and Mitchell did not go in; Murray and Brown never came back. ‘The five of us shipped on the steam- ship Virgifian of the, Armerican-Ha- wailan line, under American Jag and registry, but chartered by the French governinent, I signed on as water- tender—an engine room job—but the others were on deck—that is, seamen. We left Boston for St. Nazaire with @ cargo of ammunition, bully beef, etc., and made the first trip without anything of interest happening. As we_ vere tying to.the dock at St, Nazaire, I saw a German prisoner sit- ting on a pile of lumber. I thought probably he would be hungry, so I went down into the ollers’ mess and got two slices of bread with a thick piece of beefsteak between them and | handed it to Fritz, He would not take it. At first I thought he was afraid | to, but by using several languages and signs he managed to make me under- | stand that he was not hungry—had | too much to eat, in fact. I used to think of this fellow occa- ' slonally when I was in a German pris- + on camp, and a piece of moldy bread the size of a safety-match box was ‘the generous portion of food they forced on me, with true German hos- itality, once every forty-eight hours, would not exactly have refused a beefsteak sandwich, I am afraid. But then I was not a heaven-born German, I was only a common American garby. He was full of kultur and grub; I was not full of anything. There was a large prison camp at St, Nazaire, and at one time or an- other I saw all of it. Before the war it had been used as a barracks by the French army and consisted of well- made, comfortable two-story stone buildings, floored with concrete, with auxiliary barracks of logs. The Ger- man prisoners occupied the stone buildings, while the French guards were quartered in the log houses. In- side, the houses were divided into long rooms with whitewashed walls. There was a gymnasium for the prisoners, @ canteen where they might buy most of the things you could buy anywhere else in the country, and a studlo for the painters among the prisoners. Of- ficers were separated from privetes— which was a good thing for the pri- yates—and were kept in houses sur- rounded by stovkades. Officers and es recelyed the same treatment, er, and all were given exactly the same rations and equipment as the regular French army before it went to the front. Their food consisted of bread, soup, and vino, as wine is called almost everywhere in the world. In the morning they received half a loaf of Vienna bread and coffee. At noon they each had a large dixte of thick soup, and at three in the afternoon | more bread and a bottle ef vino, The soup was more like a stew—very thick with meat and vegetables, At une of the officers’ barracks there was a cook who had been chef in the larg- est hotel in Paris before the war. All the prisoners were well clothed. Once a week, socks, underwear, soap, towels and blankets were issued to them, and every week the barracks and equipment were fumigated. They were given the best of medical atten- tion. Besides all this, they were allowed to work at their trades, if they hed nny. Ali the carpenters, cobblers, 101 { and some of them picked up more change there than they ever did in Germany, they told me. The musi-* cians formed bands and played almost every night at restaurants and » ters in the town. Those who hail no trade were allowed to work on the roads, parks, docks and at residences about the town, Talk about dear old jail! You could hot have driven the average prisoner away from there with a 14-inch gun. I used to think about them in Bran- denburg, when our boys were rushing the sentries in the hope of being bay- onetted out of their misery. While our cargo was being unloaded Spent most of my time with my grandmother, I had heard still more about the cruelty of the Huns, and Thade up my mind to get Into the ser- vice. Murray and Brown had already enlisted in the Foreign, Legion, Brown being assigned to the infantry and Murray to the French man-of-war Cas- sard. But when I spoke of my inten- tion, my grandmother cried so much that I promised her I would not enlist that time, anyway—and made the return voyage in the Virginian. We Were no sooner doaded in Boston than back to St. Nazaire we: went. CHAPTER III. In the Foreign Legion. This time I was determined to en- list. So, when we landed at St. Na- zaire, I drew my pay from the Vir- ginian and. after spending a week with my grandmother, I went out and asked the first gendarme I met where “I Went Out ang)Asked the First Gendarms;Where to Enlist.” the enlistment station was. I had to argue with him some time before he would even direct me to it. Of course I had no passport and this made him suspicious of me! The officer in Wharge of the station was no'warrer“fi his wélcome than the gendarme, und this surprised me, because’ Mturray'and Brown had no trouble at all in Joining. The French, of course, often speak of the Foreign Legion as “the ¢onvicts,” because so many legionaries are wanted by the police of thel¥ respective countries, but a criminal reedrd never had been a bar to service with the legion, and I did not see why it should be now—if they suspected me of having one, I had heard there were nota few Ger- mans in the legion—later on I became acquainted with some—and_ believe me, no Alsatian ever fought harder against the Huns than these former Deutschlanders did. It occurred to me then that if they thought I was a German, because I had no passport, I might have to prove I had been in trouble with the kaiser’s crew before they would accept me. I do not know what the real tyouble was, but I solved the problem by showing them my dis- charge papers from the American vy. Even then, they were suspicious e they thought I was too young to have been a ©, P, O. When they challenged me on this point, I said I would prove it to them by ‘aking an examination, They examined me very carefully, in English, although I know enough French to get by on a subject like gunnery. But foreign officers are very proud of their Rnowledge of English— und most of them can speak it—and I think this one wanted to show off, as you might say. Anyway, I passed my examination without any trouble, was accepted for service in the For- eign Legion and received my commis- sion as gunner, dated Friday, January 1, 1915, There is no use in my describing the Foreign Legion, It is one of the most famous fighting orgunizations in the world, and has made a wonderful rec- ord during the war. When I joined La Legion, it numbered about 60,000 men, Today it has less than 8,000. They say that since August, 1914, the legion has been wiped out three times, and that there are only a few men still ip service who belonged to the original legion. I believe it to be true, In January of this year the French gov- ernment decided to let the legion die. I was sorry to hear it. The legion- naires were a fine body of men, and | wonderful fighters. But the whole | civilized world is now fighting the Hus, and Americans do not have to enlist with the French or the Limeys any longer. But one thing about the legion, that I find many people do not know, is that the legionnaires are used for either land or sea service. They are sent wher ever they can be used, I do not know whether this was the case before the present war—I think not—but In my time, many of the men were put on and painters were kept busy, | Bhi . Most people, however, have the 0 The Daily Tribnne Is the Largest Paper in Central .of such stuff at Spezia, {dea that tliey are Only used in the in- fantry. With my commission as funner, I cecelved orders to go to Brest and join the dreaidnaught Cassard. This as- Signment tickled me, for my pal Mur- fay was aboard, and I had expected trouble in transferring to his ship in case I was assigned elsewhere. We hud framed it up to stick together as long as we could. We did, too. Murray was as glad as I was when { came aboard, and he told me he had heard Brown, our other pal, had been made a sergeant in another regiment of the legion. We were both surprised at some of the differences between the French navy and ours, but after we got used to it, we thought many of their cus- toms Improvements over ours. But we could not get used to it, at first. For instance, on an American ship, when you are pounding your ear in a nice warm Lammock and It is time to re- lleve the watch on deck, like as not you will be awakened gen‘ly by a burly garby armed with a fairy wand about the size of a bed slat, whereas in French ships, when they call the watch, you would think you were in a swell hotel and had left word at the desk. It was hard to turn out at first, without the aid of a club, and harder still to break ourselves of the habit of calling our relief in the gay and festive American manner, but, as I Say, we got to like it after a while. Then, too, they do not do any hazing a the French navy, and this surprised us. We had expected to go through the mill just as we did when‘we joined he American service, but nobody slung a hand at us. On the contrary, every zarby aboard was kind and decent and extremely courteous, and the fact that we were from the Statés counted a lot with them, They used to brag about t to the crews of other ships that were aot so honored, But this kindness we might have ex- pected, It is just like Frenchmen in any walk of life. With hardly an ex- ception, I have never met one of this fationality who was not anxious to help you in every way he could; ex- tremely generous, though not reckless with small change, and almost always cheery and there with a smile in any weather. A fellow asked me once why it was that almost the whole world loves the French, and I told him It was because the French love almost the Whole world, and show it. And I think that Is the reason, too. About the only way you can describe the Poilus, on land or sea, is that they are gentle, That is, you always think that word when you one and talk to him—unless you happen to see him within bayonet distance of Fritz. The French sailors sleep between decks in bunks, instead of hammocks, and as I had not slept in a bunk since my Southerndown days, it was pretty hard on me. So I got hold of some heaving line, which is one-quarter-inch rope, and rigged up a hammock, In my spare time I taught the others how to make them, and pretty soon every- body was doing it. When I taught the sailors to make hammocks, I figured, of course, that they would use them as we did—that ep in them, They were greatly sed at first, but after they had tried the stunt of getting in and stay- ing in, it was another story, A ham- mock is like some other things—it works while you sleep—and if you are hot on to it, you spend most of your sleeping time hitting the floor, Our gun captain thought I had put over a trick hammock on him, but I did not need to; every hammock Is a trick hammock, rs Also, I taught them the way we make mats out of rope, to use while sleeping on the steel gratings near the entrance to stoke holes, In cold weath- er this part of the ship is more com- fortable than the ordinary sleeping quarters, but without a mat it gets too hot. American soldiers and gailors get the best food in the world, but while the French navy chow was not fancy, it was clean and hearty, as they say fown East. For breakfast we had bread and coffeé and sardines; at noon a boiled dinner, mostly beans, which were old friends of mine, and of the well-named navy variety; at four in the afternoon, a pint of vino,“and at six, a supper of soup, coffee, bread and beans, Although the French “seventy-five” is the best gun In the world, their na- val guns are not as good as ours, and their gunners are mostly older men. But they will give a youngster a gun rating if he shows the stuff. Shortly after I went aboard the Cas- sard, we received instructtyns to pro- ceed to Spezia, Italy, the large Italian naval base. The voyage was without incident, but when we dropped anchor in zin, the Italian port officials quarantined us for fourteen days on account of smallpox. During this period yur food was pretty bad; in fact, the meat became rotten, This could hard- y have happened on an American ship, because they are provisioned with canned stuff and preserved meats, but the French ships, ike the Italian, de- pend on live stock, fresh vegetables, ste., which they carry on board, and had expected to get a large supply Long before the fourteen days were up we were ut of these things, and had to live on anything we could get hold of—mostly hardtack, coffee and cocoa, We loaded a cargo of airplanes for he Italian aviators at the French fly- hg schools, and started back to Brest. On the way back we had target prac- Uce. In fact, at most times on the open seu, it was a regular part of the routine. It was during one of these practices that the French officers wanted to Gnd out what the Yankee gunner knew about gunnery. At a range of_elght we LIBERTY Bonds to Support Soldiers. miles, while the ship was making elght knots an hour, with a fourteen-inch gun I scored three d’s—that is, three After direct hits out of five trials. that there was no question about it. As a result, I was awarded three bars. “With a Fourteen-Inch Gun I Scored Three D's.” These bars, which are strips of red braid, are worn on the left sleeve, and signify extra marksmanship. I also received two hundred and fifty francs, or about fifty dollars in American money, and fourteen days’ shore | All this made me very angry, oh, y much wrought up Indeed—not! I saw a merry life for myself on the French rolling wave if they felt that Way about gunnery, I spent most of my lea with my grandmother in St, Nazaire, except for a short trip I made to a star-shell fac- tory. This factory was just about like one I say later somewhere in Amer- jea, only in the French works, all the hands were women, Only the guards were men, and they were “blesses” (wounded}, When my leave was up and I said good-by to my grandmother, she man- aged a smile for me, though I could see that it was pretty stiff work, And without getting soft, or anythi that, I can tell you that smile stayed with me and it did me more good than you would believe, because it gave me something good to think about when I was up against the real thing. I hope a lot of you people who read this book are women, because I have had it in mind for some time to tell all the women I could a little thing they can do that will help u lot. Iam not trying to he fancy about it, and I hope you will take it from me the way I mean It, When you say good-by to or your husband or your sw work up a smile for him. What you want to do is to give him something he can think about ove there, and some- thing he will like to think about. Ther is so much dirt, and blood, and hu and cold, and all that around you, t you have just got to quit thir about it, or you wil? go crazy. And so, when you can think about something nice, you can pretty nearly forget all the rest for a while. The nicest things you can think about are the things you liked back home. Now, you can take it from me that what your boy will lke to remember the best of all is your face with a smile on it, He has got enough hell on his hands without a lot of weeps to re- member, if you will excuse the word. But don’t forget that the chances are on his side that he gets back to you; the figures prove it. That will help you some. At that, it will be hard work; you will feel more like erying, and so will he, maybe. But smile for him. ‘That smile is your bit, I will back a smile against the weeps in a race to Berlin any time. So Iam telling you, and I cannot make it strong enough—send him away with a smile. CHAPTER Iv, On the Firing Line. When I reported on the Cassard after my fourteen days’ leave, I was detailed with a detachment of the legion to go to the Flanders front, I changed into the regular uniform of the legion, which fs ‘about like that of the infantry, with the regimental badge—a seven-flamed grenade. We traveled from Brest by rail, in third-class cars, passing through La Havre and St. Pol, and finally at Bergues, the trip to Dixmude by truck—a di tance of about twenty miles. We car ried no rations with us, but at «ertain places along the line the train stopped, and we got out to eat our meals, At every railroad station they have booths or counters, and French girls work day and night feeding the Poilus. It was a wonderful sight to see these girls, and it made you feel good to think you were going to fight for them. It was not only what they did, but the way they did ft, and it is at things like this that the French beat the world. of t they saw took s' ‘They could tell just what kind and atment each Pollu needed, to it that he got it. T jal pains with the men of the legion, because, as they say, we are “strangers,” and that means, “the best we have {# yours” to the French. These French women, yourg and old, could be a mother and a sweetheart and a to any hairy sister all ut the same ti old vonvict in the le vn, and do it in a way that made him feel like a lit- tle boy at the time and a rich church member afterwards. The only thing rriving | From Bergues we made | __Page Five = {s probably Just history by 1ey are still using trenches probably look entirely dif- Ste that it now. If But when I was/at Dixmude they were something like this: Behind the series of front-line re reserve trenches; in seven miles away, and still farther back are the billets. These y be houses or bar or ruined fies—any place t can possibly d for quartering troops when 3 he this case five to . and fourteen to sixteen days in the erve trenches. Th back to the billets for ix or eight 4: ys. * not allowed to chance our t in the fron not even to remove tion, N ach as ui would they | ton your shirt, u inspe the: an inspection of ide tion disks. We wore a disk at the wrist and another around the neck. You know the gag about the disks, of course: If your arm is blown off they can tell who you are by the neck disk; if your head is blown off, they do not care who you are. In the reserve trenche you can vurself more comfc . but you cannot go to such extreme lengths of luxury as changing your clothes en- tirely. That Is for billets, where you spend most of your time b. ch ng clothes, ping and Believe me, a billet is great stuf is ike a sort of temporary heaven. Of course you know what the word m means. Let us hope you er know what the cooties es mean. When you get in the trenches, you take a course in the natural history of bugs, lice, rats and every kind of pest that has ever been tnvented. It is funny to see some of th comers when they first discove a cootie on them. Some of them cry. If they really knew what It was going to be like they would do worse than that, ma ‘. Then they start hunting all over each other, just Ike monkeys, They team up for this purpose, and many times It is in this way that a couple ef men get to be trench partners and come to be pals for life—which may not be a long time at that. In the front-line trenghes it is more comfortable to fall asleep on the para- pet fire-step than in the dugouts, be- cause the cootles are thicker down below, and they simply will not give you a minute’s-rest. They certainly are active little pests, We used to make back seratchers out of certain weapons that had flexible handles, but never had time to use them when we needed them most, We were given bottles of a liquid which smelled like lysol and were sup- posed to soak our clothes in it. It was thought that the cooties would object to the smell and quit k, Well, n cootie that conld stand our clothes without the dope on them would not be bothered by a Httle thing like this stuff. Also, our clothes got so sour and horrible smelling that they hurt our noses worse than the cooties, They certainly were game little devils, and came right back at us. So most of the pollus threw the dope at Fritz and fought the cooties hand to hand, There was plenty of food in the hes most of the time, though once 1 while, during a heavy bombard- ment, the fatigue—usunlly a corporal’s guard—would get killed in the com- munication trenches and we would not have time to get out to the fatigue and rescue the grub they were bringing. Sometimes you coukd not find elther the fatigue or the grub when you got to the polut where they had been hit, But, as I say, we were well fed most of the time, and got Second and third helpings until we had to o our belts. But as the Limeys s: Dimey, the chuck was rough.” They served a thick soup of meat and vege bles in bowls the size of wush ba- black coffee with or without mostly. without!—and plenty ew- vo! f bread. (To be concluded tomorrow.) “STOLEN ORDERS” HAS REALISTIC GAMBLING SCENE t tin, 1 fashionable nbling clab rat t um This i 1 nee hown r Orders” and i af the le r meth f ash nt of m the news- ire, Kitty Gor- 1 Ameri- 2 nd ed of an un- ur uke big bills »se business it is apparently very facility to that end Blackwell, MacQuarrie,/and Madge Evans enact belief prevails t cific n- s 1,000 Wyoming, Carries the Latest News