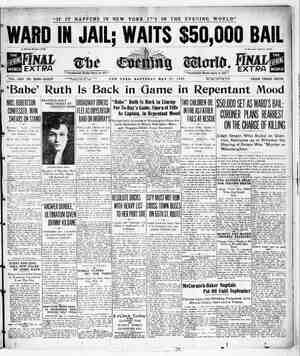

The evening world. Newspaper, May 27, 1922, Page 14

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

| breathless, choking sensa- F pulled out his checkbook 4 z ‘wrote. N the way Wilbur tried to figure out how it had hap- pened. Tt couldn't have hap- pened. But it had happened. Fle had spent half their savings in one lump. He had contracted to spend the other half. Anita was Spending their savings too—in slight- ty smaller lumps. How much had the President meant by a ‘substantial Talse?’’ Had the president actually Put the raise through? It ought to appear in his monthly salary check on the last day of February. But would 2 The president might think the mew salary should begin with March. He bought 2 bunch of violets for Anita at the corner. Could he face her? Could he keep his awful secret? He shut his teeth savagely. nita met him at the door. “Oh, Wilbur," she cried. ‘The Ereatest piece of luck in the world— Aunt Emma's girandoles — they've aent them to us—they're my share of her things!"’ “Girandoles?”’ said Wilbur weakly. ."Yew—mafvelous French mirrors— real antiques—heirlooms! Get the Janitor to open them up—but he must be horribly carecul!"* “Don't you think we'd better let them stay packed until we get out to the country?’ he asked. “Oh, no-0-0-0!"" Wilbur got the janitor up and the boxes open. “They set one of the doles on the buffet at one end of dining room and the other on the side table opposite. Anita looked at one: the massive frame, with its delicate and elaborate carving, the slender, curving cande- Jabra, and in the centre the round mir- ror that mysteriously reflected the whole room. It was a fine example of the craftsmanship of another age than ours. Isn't it a perfect b-e-auty!” she cried. The phrase reminded Wilbur un- Wappily of the salesman’s remark about the Smithson twin-two. He hoped his unhappiness didn’t show in his face. Anita had turned round to look at the other girandole. “Of course,” she explained, “they don't show off properly with this fur- niture of ours and in this little room And not properly hung. But you wait! They'll be the keynote." =-Keynote?" said Wilbur, stupidly. Of course," said Anita. ‘That's sthe way a decorator works. He takes some one perfect thing as a start and then builds around it—gets everything to-go with it. These girandoles are ‘the perfect thing, the true Victoria! ie. Oh, Wilbur, we'll just have to have that lovely tilt-top table’"—— “I thought it cost three hundred “Only two hundred and ninety-five," the perfect thing. at either end of “living room and that tilt-top Brien was a big table, you know— that English. sofa, why, we'l) hardly need another thing!" F ~The check he had given the sales- Man of the Smithson car would just CHAPTER XX. - (Concluded) IANA drew a quick breath. While the man was still in the adjoining room the mo- \fhy. Ment for which she was seemed interminable. And ‘he wished he had not gone. He Stood between her and—what? For the first time since the coming of Saint Hubert she was alone with him, really alone. Only a curtain separated them, a curtain that she could not Pass. She longed to go to him, but she'did not dare. She was pulled be- tween love and fear, and for a mo- ment fear was in the ascendant. She » shivered, and @ sob rose in her throat. Bhe only wanted to Ite in his arms and sob her heart out against his. ‘She was starving for the touch of his hands, suffering horribly. She slid down on to her knees, burying her face in the couch. “Oh, God! Give me his love!"’ she kept whispering in agonised entreaty, until the recollection of the night, months before, when in the same pos- ture she had prayed that God's curse might fall on him, sent a shudder through her, “I didn't mean it, “Oh, dear God! didn't know. "t mean it.”’ _/ ‘There was silence tn the next room ‘except for the striking of a match that came with monotonous regular- ity. Another hour of waiting would drive her mad. She set her teeth and, crossing the room, slipped noiselessly between the curtains. She looked at him hungrily, her ranging slowly over the long of him and lingering on his she moaned. I didn’t mean it. I + Take it back. I 1" she whispered, Hfted his head slowly and looked and the sight of his face sent om to her knees beside him, her clutching the breast of his soft caught her groping hands, and » pulled her gently to her feet, fingers clenched round hers, look- f down at her strangely. Then he from her without a word, and open the flap of the tent, it back and stood in the open doorway stariag out into the night. “What is it?" she whispered again breathlessly. TE ITN ao me about pay for the tilt-top table and the sofa Anita wanted, but it did not seem to Wilbur a good time to say so. ILBUR spent most ot his lunch hours looking at the perfect pieces of furniture Anita discovered in her shopping tours, Sometimes he got up enough courage to shake his head du- biously over Anita's enthusiasm of the moment; more often he didn't. The only way to still her excitement over the house she was going to have would be to tell her about the car. He couldn't do that. Every time he thought about {t he dubbedhimseif a selfish hound; and every time he saw a Smithson car in the street he auto- matically stopped to admire it—uniess he was with Anita, He had a sand- wich and a glass of milk for lunch whenever he was alone, and took a surprising comfort in the seventy-five or eighty cents he saved thereby, The last day of February came— 5 o'clock of the last day of February came. At one minute after § the young man from the Treasurer's office came to Wilbur's desk with the envelope containing Wilbur's check. Wilbur thrust the envelope casually into his pocket. The moment thi young man had passed on Wilbur tore open the envelope. The check was the same as usual. His increase had not yet appeared. Wilbur ran a /lind ad, the next day in the want columns of an after- noon paper, offering to sell his con- tract for a Smithson. He got adozen offers, but the best of them involved a loss of $250 of his original $500. Wilbur pinned his hope on the en- yelope he would open March 31, and when March 81 brought the same old check Wilbur went Into executive session with himself. He decided that {f he did not have a bigger wheck on April 80 he would speak to the President. It was not good psychol- ogy to raise the question with the President. It was much better for the President to speak first. But if the President continued to be dumb Wilbur would simply have to act. They moved to Sparborough on April 14. When Wilbur got back to his oMece on the 17th he had a letter from the Smithson salesman notify- ing him that his car was ready and would be delivered on payment of another $500 in cash and five notes for $104 each. Wilbur had a crazy impulse to draw the chéck and sign the notes and drive the new car out to Sparborovgh. Perhaps if Anita saw it in all its brand-newness—the perfect thing--she would forgive him, He wondere how much money they had spent on furniture, He avoided keeping track of it on purpose, and the bills hadn't come in yet. He had an awful feeling that it might run over $2,000, And he would have to pay it all within two months— three at the most. Wilbur did not draw the check for the second $600, Instead he bought gardenias for Anita. Sunday proved one of those har- bingers of summer that are more lovely than summer ever is. ‘Wilbur and Anita took a long walk in the afternoon exploring Sparborough, and re im ie THE EVENING WORLD, SATURDAY, MAY 27, 1922. winding up at thelr friends’, the Bingletons, for tea It was dark when they approached thelr own little white house, with its green blinds and its Dutch gable and its neat hedge of box “Look,” said Anita softly. The liv- ing room windows, with their small, Square panes, were patterns of yel- low light. Anita took his arm as they walked up the brick path to the feont door. “And to think—It's al ready just as perfect inside as it is out.” Wilbur threw open the front door with a glow of pride. They paused in the hall to survey the living room through the wide arch. There was the deep-cushioned sofa in front of the fireplace, the lovely tilt-top table with its Victorian lamp of glass, and at either end wero girandoles refiect- Ing the room, enlarging St. What did cost matter? Who could think of money at such a time? “Wilbur,” sald Anita, “what about our raise? Hasn't the President said anything?” Wilbur frowned. Wilbur cleared his throat. Wilbur put his hands in hi pockets. 0,” he sald. “I think it's time you spoke to him about it, He hasn't kept his prom- tse.” “T think he wanted to try me out before he decided just how much the raise would be,” sald Wilbur. “It isn't good psychology for me to speak first, at least not just now.” “But what if he doesn’t speak ‘at all? We can’t go on like this much longer.” “Why can't we go on like this?” “We're spending money just as it our income had been increased, and it hasn't.” “Tt will be," said Wilbur, "You know our annual falesmeén’s conver- tion js coming on next week, It will give me my best chance.to show what I can do. When I get back I will speak to the President.” “T would,” said Anita slowly, That means,"’ Anita continued, ‘that you'll be away from home a whole week, doesn't it?’ “Ten days,” said Wilbur. “Tam to go on ahead to Cleveland and get some charts ready for the opening day.” “I wish you didn’t have to leave now,” said Anita. “So do I," Wilbur said, but {t wasn't true. Wilbur wanted to get away for ten days. Wilbur wanted a respite. ILBUR put in so busy a ten days in Cleveland that he hardly thought about the Smithson car or his finan- cial predicament or the rais¢ he might have to ask for. But he could no Iénger put these things out of his mind when, at ten minutes after five on the third of May he reached his desk in Broad Street. The offices of Whitworth & Co. were néarly empty. Wilbur felt very much alone as he contemplated the stack of mail on his desk. So much of it contained bills. Wilbur opened them automatically, smoothing out the folds and glancing at the totals. There was two hundred and ninety-five for the tilt-top table, Ree SAN “| CAN'T GO, AHMED, | CAN'T GOI” we start for Oran to- * he replied. “You are sending me away?” she gasped slowly. “Yer The curt monosyllable lashed her like a whip. She reeled uncer it, panting and wild-eyed. ““Why?" He did not answer and the color flamed suddenly into her face, “It is because you are tired of m she muttered at last hoarsely, “ you told me you would tire, as you tired of—those other women Her Yoice died away with an accent of hor- ror in it. He spoke at length in the same level, loneless voice, ‘*I will take you to the first desert station outside of Oran, where you can join the train. For your own sake I must not be seen with you in Oran, as I am known there," She flung up her head. Quick, sus- picious jealousy and love and pride Hh Hh Mi and two hundred and sixty for the deep-cushioned sofa, and elghty for the glass lamp. And that was only one room, Wilbur picked up a@ pencil and memorandum pad and began to jot down ttems. ‘The total came to more than fifteen hundred. And, of course, these were only the new ac- counts, When he got home he woul find the usual bill from the depart- ment store multiplied by the addition of curtains and rugs and kitchen uten- sils and garden tools and what not. Perhaps three or four hundred dol- lars. The second payment of five hundred on the car was overdue When that was paid, he would still have to pay a hundred a month for five months, to say nothing of upkeep He had $1,188 minus five hundred in bank; this made $683. His monthly salary check—but what would his monthly salary check be? The, usual monthly bills for food and rent and service would have to come out of it Would there be anything left? Wilbur guessed that, counting the car, he was perhaps two thousand dollars behind; not counting the five hundred that he must pay immediately on the car, he was fifteen hundred dollars behind. Wilbur wondered if a clerk was stil! lingering in the treasurer's office, He could not bear to go home without knowing the amount of his salary check for April. Wilbur tried the in ner-office telephone, but it was no use ‘The treasurer's office did not answer> He woulll have to wait until morning to know. Weartly Wilbur picked up his bag He must catch the first train to Spar- borough. He must have a serious talk with Anita, He must make her see the predicament they were in. Per haps he could borrow some money anil in a year, by living very economically, they would get even again. If they sacrificed the car, they wouldn't be in so bad. They could pull out somehow Only, how could Anita live economi- cally? Women had no idea of the value of money, no proper fear of debts, no business sense. Anita had no real conception of their income. She had wants. An income was something that supplied them. Wilbur bought some pale yellow roses for Anita at the entrance of the Grand Central Terminal. They cost four dollars. But what difference did four dollars make when you were broke? Wilbur's bag tugged heavily at the end of his arm as he walked down the long ramp into the station. He ran plumb into the President of Whitworth and Company ‘Why, Rudge, I'm awfully glad to Bee you. Where are you gojng?”” Wilbur shook hands. “T am living out in Sparborough now." That's fine,” the President said. “That's right. I do think anybody who lives on Manhattan Island is a chump.” “We like it much better in the country." Wilbur wondered if the subject of living in the country did not lead nat- urally to the subject of an increase in salary. But he could hardly brace the President for a raise in the Grand Central Terminal. “Of course you do," said the Presi- dent. “By the way, Rudge, I hear you did a corking good job out there i ‘i jp p a contending nearly choked her. “Why don’t you speak the truth?’ she cried wildly. “Why don’t you say what you really mean—that you have no further use for me, that it amused you to take me and torture me to satisfy your whim, but the whim is passed. . . . How many times a year does Gaston take your discard- ed mistresses back to France?" He swung round swiftly and flung his arms about her, crushing her to him savagely, forgetting his strength, his eyes blazing. “God! Do you think it is easy to let you go? My Ufe will be hell without you.” His arms were like a vise hurting her, but they felt like heaven, and she clung to him speechless, her heart throbbing wildly. “I mustn't kiss you,’’ huskily, as he put her from him gently. ‘I don't think I should have the courage to let you go if I did. I didn't mean to touch you.”* He turned from her with a little gesture of weariness. Fear fied back into her eyes, don't want to go, faintly. “You don't understand. There is no other way,” he said dully. “If you really loved me you would not let me go,” she cried, with a mis- erable sob, “If I loved you?" he echoed, with a hard laugh. If I loved you! It is be- cause I love you so much that I am able to do it. If I loved you a little less I would let you stay and take your chance.” She flung out her hands appeal- ingly. “I want to stay, Alimed! 1 love you!"? she panted, desperate— for she knew his obstinate determin- ation, and she saw her chance of hap- piness slipping away. He did not move or look at her, and his brows drew together in the dreaded heavy frown, “You don't know what you are saying. You don't know what it would mear," he replied in a voice from which he had forced all expression. “If you married me you would have to live always here in the desert. I cannot leave my people, and I am—too much of an he said oy she whispered Arab to let you go alone. It would be no life for you. “You think you love me now, though God knows how you can after what I have done to you, but a time would come when you would find that your love for me did not compen- sate for your life here. And marriage with me is unthinkable. You know what I am and what I have been. You know that I am not fit to, live with, not fit to be near any decent AWAY WIVES - jn Cleveland, You're making good. You haven't forgotten what we si ut raising your salary?" "No," said Wilbur, “Well, sir,’ he said in his hearty ce," we're going to start you off And, by the way— Your new salary. v at six thousand, that's retroactive, “THE YILT-TOP TABLE WAS ALL THAT ANITA SAID IT WAS.” began Feb. 15.- I think you'll find the treasurer has a check waiting for you,’* “That's handsome of you." “Not ut all. You've got it coming have to do more than that for you," ILBUR speculated all the on how Anita would take it. He was afraid she enough, he was not disappointed him- self. He was terribly relieved. He the walk to his house. The front door swung open and Anita threw her close. He hadn't seen her for ten days. Besides he had a secret for her. delightful hour that comes after din- ner. “Thank you, sir,’ sald Wilbur, I hope it won't be long before we'll way out'to Sparborough would be bitterly disappointed. Oddly could not help smiling,as he went up arms around his neck and he held her A seoret he would withhold for that The house was lovely—there was Iflustrated by Will B. Johnstone woman. You know my devilish tem- per—it has not spared you in the past, it might not spare you in the future. You must go back to your own country, to your own people, to your own life, in which I have no place or part, and soon all this will seem only like an ugly dream." She shuddered convulsively. med! I can’t go!" she, wailed. He looked up sharply, his face livid, and tore htr hands from her face. ood God! You don't mean — I haven't—You aren't——"' he gasped hoarsely, looking down at her with a great fear in his eyes, She guessed what he meant and the color rushed into her face. The temptation to lic to him and let the consequences rest with the future was almost more than she could resist. One little word and she would be fm hisatms * * * but afterward——? It was the fear of the afterward that kept her silent. The color slowly drained from her face and she shook her ‘cad mutely. He let go her wrists, laid his hand on her shoulder and pushed her gently towavd the inner room. With a cry she flung herself on his breast, her face hidden against him, her hands clinging round his neck. ‘Ahmed! Ahmed! You are killing me, I can- not live without you, I love you and I want you. I can’t go back to the old life, Ahmed. Have pity on me." ‘A spasm crossed his face, but his mouth set firmer and he disengaged her clinging hands with relentless fingers. “| haye never been anything else," he said bitterly, “but [ am willing that you should think me a brute now rather than you should live to curse the day you ever saw me." Hie dropped her hands and turned abruptly, going back to the doorws looking out into the darkness, ‘It is é “Ane va a no getting around that. Anita had a new dress, a dress of soft dark silk that set off her small blond he And there was a leg of lamb, th roast he liked best for dinner With food, Wilbur lost his feeling that the bottom had dropped out of everything, He smiled across the yellow roses at Anita, and Anita smiled back After dinner Wilbur lit the fire that had been laid on the living-room hearth in honor of his home coming and they sat in the deep-cushioned sofa and Anita did a piece of hem- stitching while Wilbur smoked. It was the hour of charm. Wilbur could not crash into it with a discussion of money. He pushed thé “thought ‘of money from him and looked around the room so simple, so pérfect, and so expensive. And how Anita adorned it “Anitay’’ he said suddenly, new salary is six thousand a year. Anita dropped her hands. Her bit of linen fell. to the floor “Oh, Wilbur!” she cried. it, T knew it, I knew it!” She jumped up and kissed him. ‘Aren't you disappointed ?"* * “Of course not—we can do beauti- fully on six thousand.” Wilbur knew that this was the psy- chological moment to tell Anita ur “I knew NEXT SATURDAY’S COMPLETE NOV BEING A NOBODY ani . The Story of a Girl Who Never Knew What Self-Sacrifice Meant _ ORDER YOUR EVENING WORLD IN ADVANCE very late. We must start early. Go and lie down."’ She shrank back tfembling, with Piteous, stricken face and eyes filled with a great despair. She knew him ad she knew It was the end. She caught at the writing table behind her to steady herself, and het fingers touched the revolver he had laid down The contact of the metal sent a chill that seemed to strike her heart. Her mind raced forward feverishly, there were only a few hours left before the morning, before the bitter moment when she must leave behind her for- ever the surroundings that had be- come so dear, that had been her home as the old castle in England had never been. She thought of the long Journey northward, the agonized pro- traction of her misery riding beside him. The contrast between that ride, when she had lain content in the curve of his strong arm, and the ride that she would take the next day was Plognant. She closed her teeth on her trembling lip, her fingers tight- ened bn the stock of the revolver, and 4“ wild light came into her sad eyes. She could never go through with it To what end would be the hideous torture? Her life was her own to deal with. Nobody would be injured by its ter- mination, Aubrey, indeed, would bene- fit considerably. And he—? His figure was blurred through the tears that filled her eyes. Slowly she lifted the weapon clear of the table with steady fingers and brought her hand stealthily drom be- hind her. She lifted the reyolver to her tem- ple resolutely. There had been no sound to bet what was passing behind him, but th extra sense, the consciousness of im- minent danger that was strong in the desert-bred man, sprang Into active i e force within the Shelk. He turned like a flash and ‘leaped across the space that separated them, catching her hand as she pressed the trigger, and the bullet sped harmlessly an inch above her head. With his face gone suddenly ghastly he wrenched the weapon from her and flung It far into the night For & moment they stared into each other's eyes in silence, then, with a © slipped from his grasp and his feet in an agony of ter- rible weeping. With a low exclama- tion he stooped and swept her up into his arms, holding her slender, shaking figure with tender strength, pressing her head against him, his cheek on her red-gold curls. My God! child, don’t cry so. I can bear anything but chat,’ he cried brokenly. But the terrible sobs went on, and fearfully he caught her closer, strain- ing her to him convulsively, raining kisses on hér shining hair. ‘Diane, Diane,” he whispered imploringly, falling back into the soft French that seemed s0 much more natural. “Mon amour, ma bien-aimee, Ne pleures pas, je t’en prie. Je t'aime, je t’adore. Tu resteras pres de moi, tout a mot.” He laid her down, and dropped on his knees beside her, his arm wrapped round her, whispering words of pas- sionate lov Gradually the terrible shuddering passed and the gasping sobs died away, and she lay still, so still and white that he was afraid. He tried to rise to fetch some restorative. "I don’t want anything but you,” she murmured almost inaudibly. His arm tightened round her and he turned her face up to his. Her eyes were closed and the wet lashes lay black pale cheek. His lips touched them pitifully, about the car. To let her know how carefully, they should have to man- age in order to pay for it, how com- pletely it would absorb the increase in their income for a whole year. But Wilbur put off the blighting moment. “The president says that the in- crease is retroactive to February 15th,’ he said. ‘I am to get a check for it to-morrow. ’ “We'll ha to save-it, Wilbur,’’ said Anita. ‘‘We mustn't spend it.’’ “Well,” Wilbur began, ‘‘I”—— But Anita's mind had already di missed the subject. She was looking at the room, admiring their posses- sions. Now she turned to Wilbur and her eyes were soft and her lips smiled. “Isn't it perfect?” “Absolutely perfec “You wouldn't change anything “Not « thing.” “And you don’t see anything new?" Wilbur straightened up and looked about him hurriedly. ““‘Why—why"’—— he began. “Didn't you notice the girandoles were gone?” Wilbur stared first at one end of the room and then the other. The + sirandoles had been replaced by two oval mirrors with delicate gilt frames. “I bought them for fifty dollars apiece,"’ Anita said trium: ntly. e¢ asked. “Fifty dollars apiece Wilbur groaned. “Yes,” she sald, “T decided the girandoles were too good for us to keep.” “But I thought you liked them—t thought they set the keynote of the room."* “They did," Anita explained. “They set it so well that now they're gone you never missed them. They're too valuable for us to keep for a sim- Ple little house like this. The Mu- seum of Decorative Arts is paying me $1,600 for those girandoles."’ Wilbur got to his feet, “Sixteen hundred dollars!” “Sixteen hundred dollars,’ “You sold them?’ “Yes,"" Anita said, “IT did. £ thought you'd rather have a car. You have to have a car in Sparborough, really. Wouldn't you RATHER have a car?” Anita looked at Wilbur with eves ‘o innocent that he was disarmed, He had deceived her. He had been selfish. And now he was saved — saved by the girandoles, By a mira- cle he could confeas his sin. “Anita,"’ he began humbly. “Anita I've wanted to tell you all the time what a—what a selfish fool Mm been." Anita smiled up at him “A fool about what?’ About a car."’ “Oh,” said Anita, “IT know all about the car. The salesman called up the day you left. He was s0 sorry ha couldn't reach you. He said you'd paid nearly half the price, and he was ready to deliver the car any day [ suggested.”” “But it—the notes—I was to give him notes for the balanc “I know," Anita said. “But I don't like going into debt I paid the bel- ance in cash." ; “You, did." “Yes—with my girandoles mone The car is down at the garage and the salesman is sending a man around to-morrow to give me a driving son." Wilbur looked at forced his f Anita. Wilbur e into the lines of stern masculinity, of a,husband dealing with a wife. But Anita looked up at him with eyes so round and so soft that he could not be a stern husband. He could only put both arms around ler and hold her tightly against his heart. (Copyright. All Rights Reserve Printed by arrangement with Met Newspaper Service, New York. ELETTE Brown “Diane, wil you never look at me again?” His voice was almost bum- ble. Her eyes quivered a moment and then opened slowly, looking up into his with a still-lingering fear in them. “Yon won't send me away?" she whispered pleadingly, like a terrified child. A hard sob broke from him and he kissed her trembling lips fiercely. ever!" he said sternly. “I will never let you go now, My God! If you knew how I wanted you. If you knew what it cost me to send you away. Pray God I keep you happy. You know the worst of me, poor child—you will have a devil for a husband."* The color stole back slowly into her face and a little tremulous smile curved her lips. She slid her arm up and round his neck, drawing his head down, ‘I am not afraid,"” she mur- mured slowly. “I am not afraid of anything with your arms round me, my desert lover, Ahmed! Monsieg- neur! (THE END.) Love Will Never Die By John Hunter A Story for the Young of Heart — BEGINS — MONDAY, MAY 29 THE’ EVENING WORLD ¢ € ¢ e