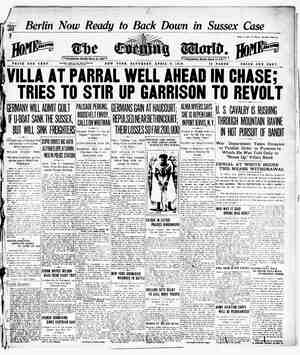

The evening world. Newspaper, April 8, 1916, Page 11

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

6YNOPSIS OF PREC Arnold Hastings is secretary to John Maraland, jetion magnate, and in eneaged to Mars: as dauahter, Darcie Addon Bergstrom at ‘® right-hand man. iy also in love with y 5 Bergst in Marsland’ Gechres Hastings aa an fia vie that the retary’e real name is md that an tae trom.” Hastings faa Fs “tend. “fathers dead ts Tee neadeents Gut of rk digta sents foom aod prepares.“ imoelt Se’ ur’soterrupted yp triewd, who uades him, (rs From, him owt rev jas secures letters supposed! wn father wud fins team to fone. and, written by his oubt their genu- CHAPTER XV. (Oontinued,) After Fifteen Years. WANT you to look at these,” he said calmly, Uke @ professor ad- dressing a student. “One and all contain @ very simple fact which your mother ‘nd you evidently failed to observe, I happened to notice it, however, the first time I saw them, I refer to ‘the watermark.” “The watermark?" repeated Forbes mechanically, “Yes. Of course, you know all note- paper bears a name or trade maik— the watermark as it's called—but it's impossible to see it unless one holde the paper to the light. Now look at this.” He held one of the letters against the strong incandescent light, and, watermarked on the paper, Forbes saw for the first time the words: “Stork’s Fine Linen.” “Now look at this and this and dhis,” added Mr. Blunt, picking up the remaining five letters and hold- ing them as he had done the other, ‘ou see? Stork's Superfine, Stork's Irish Linen, Stork’s Far-Away Mail, Stork’s Cream Wove, Stork’s Old irish Parchment. In short, although six different qualities of paper are represented here, they are one and all manufactured by Stork—a@ Mas: chusetts concern, Yet these letters @re supposed to have been written in ix different cities of Europe. “Doesn't it seem rather strange that American note paper, and from the same firm, should have been used in each instance? Isn't it pulling the long arm of coincidence right out of the socket? It certainly struck me 80, especially as I had an idea that the Stork concern had no export trade. However, to be sure, I made inquiries from the firm, and’ found I Was right; they have no export trade and none of their paper is sold on the Continent. Theretore, this paper was bought here.” “Then—then you mean my father must have taken a stock of such paper with him? “No, I don't. That's possible, but not probable; very improbable, in fact. Your father is supposed to have left Chicago on a Thursday night in @ great hurry and to have sailed on the St. Paul, leaving New York early Saturday morning. He mentions chose facts, you remember, in his let. ter, He took no other belongings, no possessions of any kind in the way of clothes; why, then, should he lay in @ stock of note paper and of halt @ dozen different qualities? Wouldn't thet be sheer idiocy? Not, mind you, mei ‘ly one box of paper, but six di ferent brands. Doesn't the imple little fact of those watermarks—un- observed by ninety-nine people out of @ hundred—raise a series of questions that refuse to be satisfactorily a wered? Forbe: 66 spoke with difficulty, you Inferring, then, that my father did not write those letters?” “Are “I am. Those letters, or the major- ity of them, I venture to say, were written here in America; they were composed and written here and mailed in the different cities whose stamps and postmarks they bear.” “But it's my father’s writing!" ex. claimed Forbe ll swear to that! My mother could have sworn to it a “Your father,” replied Mr, Blunt, ‘wrote an extremely plain, legible hand, very easy to imitate by any one at all gifted that way. M, Blanco, the greatest handwriting expert perhap: fn the world, will tell you #0, I found occasion to acquire a speciinen of > your father’s writing, and M. Blanc: has compared it with these letters, I , know a little about science, but he can explain to you far better than I wherein lie all the little differences, though they are remarkably good forgeries. Forbes sat down, the sweat pearl- ing his brow. “You mean then, my father wasn't a thief? You mean he didn’t commit suicide?” “No, your mother's faith was Justi. fied. Forbes, your father was Tmur- dered" “M-murdered!" “Yes, [ must tell you the truth. He was kiled in defense of that seventy- five thousand dollars he has been ac- cused of stealing, The unjust blot has stood against his name and mem- ory for fifteen years, but at last time and events are going to do him jus- tice, Now, before 1 go any further, you must give me your promise not to leave these rooms to-night, but to let this question rest entirely with the law, where it properly belongs. I mean the question of bringing your father’s murderer to justice, Have L promise?" ‘ou have, Mr. Blunt,” replied 3, with pale, set lips, Ferhe ‘famous detective nodded and picked up the "suicide letter,” the last letter written supposedly by Robert Forbes in London. of “Dbis ts a masterpiece,” pronounced r, Blunt, “They are all gems in cir way, but this one especially. can hardly believe the writer was rely faking up the emotions he so vidly depicts, writing things he did not even feel remotely. And, as in ‘the other letters, it shows an intimate knowledge of your father’s affair Yes, they are the work of a very clever sort of person, but even the cleverest make mistakes, and it's an axiom in our profession that every crime / as its ‘monument,’ “Now this very clever person made takes, left two monuments, in e writing of these letters; the first Gave sseu—failing +o remember The Mystery Romance of A Sealed Box and a Strange Heritage that note paper is watermarked. He knew enough to get different qualities of paper—seeing they were to be mailed from different cities—but he neither saw nor thought of the water- mark, Without those watermarks none could say this paper was not % purchased abroad. “The second and far more deadly monument is present in this suicide letter; here the writer's cleverness has gone a little too far and got him into serious trouble, You observe these blots caused, supposedly, by your father’s tears; that was a last artistic, realistic touch which, no doubt, at the time occasioned the writer much satisfaction, Let us see, however, what this inspiration, after fifteen years, has cost him.” Mr. Blunt produced a small, power- ful magnifying glass, and held tt over the blots. “See anything?” Forbes shook his head, “Just a few faint, wavy lines.” ‘Lisping Jimmie” then brought out a@ small tube filled with a fine white powder; very softly he dusted the powder over the blots, spreading It evenly with the aid of a fine camel's hair brush. And slowly, before ‘orbes's eyes, the vague, wavy lines which he had seen began to assume @ certain definite design, standing out white against the black, “Now, look,” said Mr. Blount, hold- ing the magnifying glas “Fingerprints!” exclaimed Forbes in a low voice, nodded the other. ter thumb and forfinger of the writ the man responsible for your fathe: death,” Forbes could make no reply; he was still staring at the fingerprints os if fascinated. There was something bor- rific about them, something uncanny about the whole performance, in fact, as if they had taken shape and form in obedience to the wave of a magi- clan's wand. And to think those blots had been there during all the year: holding @ secret which at last had been wrenched from them by advanc- ing science. “They aren't very good,” said Mr. Blunt apologetically, “for, of course, this isn’t the first time they've been subjected to such a process; they've been enlarged and photographed at headquarters. But, considering the lapse of time, they were remarkable, All the letters, however, were pre- served carefully from tho light, and uu notice the ink hasn't faded in the least, but looks as fresh as the day it was penned. There's something rather grim and ironic in all this, for, of course, when the letters were written, the subject of fingerprints wasn't unl- versally known and hadn't become an exact science. Nowadays you'll find your criminal taking particularly good care not to leave such a deadly trade mark; but at that time, if the writer was aware what he had done in making those artistic blots, there was no reason to attach any signifi- cance to it, He had no reason to suspect he was indelibly expressing his own guilt. ‘Now,” continued Mr, Blunt, pro- ducing a sheet of paper from Ris wallet, “here we have another ex- hibit—another dexter thumb and fore- finger. Here, however, black powder has of necessity been employed in- stead of white, This also has been photographed at headquarters, and, unlike the others, is perfectly clear and distinct in every particular; you can mark every line in the whorli “Isn't this @ blank page from a ledger?” asked Forbes, taking the sheet. “Yes, You see, sometimes it's nec- essary to secure finger prints without a subject's knowledge, and in such cases blank paper is used. Say, for instance, 1 want yours; I—or, if lam known to you, one of my operatives does the trick—call in the guise of a book agent, I open and show you, say, this ledger and induce you to ex- amine it. While doing so my hands accidentally rest on yours for a mo- ment, pressing your fingers against the paper, Of course, no mark is left, no impression apparent, but after- ward, if the thing has been done properly, a little black powder and a camel's hair brush will bring out just such clear impressions as these. “I needn't go into the infallibility of finger prints; you know that out of countless thousands no two are alike, and that thia system of identi- fication is now recognized and em- ployed throughout the world, you may say. Now let us carefully compare these two exhibits, these two prints of dex- ter thumb and forefinger; notwith- standing that those on the letter are far from being perfect I think that, even to an inexperienced eye, the sim- ‘larity of the whoris will be apparent, Here, take the glass.” Forbes, in a high state of excite- ment, obeyed, “Yes, L see. I see!" he exclaimed at length. “"Phey are alike. Whose— whose are these?” placing a trembling ‘Whose are finger on the ledger leaf. they?" yed him long and stead- you an idea, Forbes?" ‘Ni How could Why should I? Whose are they? Teil me “John Marsland's!" CHAPTER XVI. tage Is Set for a Visitor, ORBES dropped the glass with a crash, pushed away the paper as if he had touched a snake, and cow- in his chair, white and The § I | ered back shaking. “Marsland’s!" he cried hoarsely, Ho covered his eyes with palsied hands, as if to shut out his own thoughts, They are Marsiand's," repeated Mr, Blunt with set lips, ‘That's ag true as you sit in that chair, Don't you see now why he hated you? This was the irreparable wrong done"—— He was interrupted by the violent ringing of the desk telephone, tho sanctity of which, while demolishing the building, had been another of the Empire Company's vexatious prob- lems, Forbes roused himself with an et- fort and picked up the receiver, “That may be for me," said Mr, Blunt, "I told them I was coming here and left the number,’ “It is for you," replied Wor! passing over the instrument. “°C fleman by the aame of Smith.” HOW po You Do SxHorty! ITS A C4 ts PLEASURE Rise WHISKERS ! a 4 SA \ 2 The Evening World Daily Magazine, Saturday, April 8. 1916 You KNow A LOT oF QUEER eons Don'T secret— as the heroine of story you have read. while to read it. MERE CIRCU ACQUAIN TANCES, “One of my operatives,” nodded the detective. He listened at the instrument with- out comment and rang off with a curt “AML right.” “Marsland will be here in about fit- teen minutes, Forbes.” “Will he?" exclaimed the latter hoarsely. “Then he comes at his own risk!" “There will be no ri member your promise. “I'm not going to him; he's coming to me, That wasn't in the promise “Your promise was to let the law take its course,” replied Mr, Blunt firmly, “I didn't know Marsiand was coming here to-night; though, at that, I thought it not unlikely. He's been ‘tailed’ for the past week, and Mr. Smith, one of my operatives assigned to shadowing him, heard him give this address to the chauffeur of @ taxt. That's why he called me up.” “And—and do you expect me to see him after this?” exclaimed Forbes, pointing to the finger prints. “Do you expect me to see him as if nothing had happened? You say he killed my father; then, if so, he's a double mur- derer, for he also Killed the sister never saw, that nev ruined my mother’s life! “Sit down,” said Mr. pull yourself together, I know all you must feel, but you've got to piay a man's part, not a child's, and I know you'll do so. There's no occasion for taking the law into your own hands, If I can't rely on you absolutely to keep control of yourself I'll meet Marsland outside. He'll be trailed here by Smith.” “You're right,” replied Forbes in a Forbes. Re- Blunt, low volce, "I promise to keep myself in hand, Why is Marsland coming here?” don’t know, but I imagine it's for one of two reasonsto put you out of the way or to make a confession— I can't say which. In either case we'll be dealing with a desperate man, Marsland, I should judge, is on the verge of madness; tf not actually in sane, then he's mighty near it. There's been @ great change in him; you no- ticed it, T suppose?” Forbes nodded. He remembered the nervous hands, twitching mouth, and the occasional glare of the eye! also Marsland's expression at his parting words: “Don't push me too ‘ar.’ “Marsland’s condition has been at- tributed to overwork,” pursued Blunt, “but it's nothing but the working of fear and conscience, and it began when he learned that night from Hergstrom your name was Forbes, not Hastings; that you were the son of his victim, For fitteen years he had managed to forget, but now tho crime suddenly rose up to confront him, as it were. The knowledge that you were the son of Robert Forbes must have been absolutely paralyz- ng. Forbes nodded again, remembering how Marsland had acted on that oo: casion, Small wonder Bergstrom had been permitted to run on as he pleased, for Marsiand had been ab- solutely incapable of thought or ag- ton, "To Marsland,” continued Blunt, “you became, unconsclously, a sort of Nemesis; he got rid of you in one direction only to have you crop up in another; you kept crossing him at every turn, You were right; he wanted to drive you out of the city, out of the country, if possible, out of his life and thoughts. He wanted toy forget, but you wouldn't him HY bas tried to find forgetfulness in drugs and dissipation, with the re sult that he has become a wreck. This holdup was the last straw, and it has cost him his position with the Empire Company.” “What? "Yes, I understand he has re- signed. ‘orbes was silent a moment, then said: “Do you think he has any idea that you know all this? I mean about my father.” “That I don’t know. But Marsland knows me, and he knows also that you and I are intimate—you remember he met me the other day as I was coming in here, Hoe also knows—and has for @ month past—that the remains of hi victim have been discovered at last.’ Forbes made an incoherent excla- mation. sald Blunt. “Do you ecount in the papers? They were unearthed in the cellar of a Chicago house,” Forbes sat, white and motionless, feeling almost physically nauseated. Did he remember? There arose be- fore his mind's eye the scene in the train, Hergstrom holding out the even- ing paper, the flat, white dimple on his nose, and aski if he had seen the sensational news. Bergstrom had merely used it a method of intro- ducing Chicago as a subject of con- versation; he had his own ends to serve, and had not the remotest idea that the gruesome discovery was tl remains of that Robert Forbes whom he had known, whose theft from the bank he had every reason to credit, whose disgrace he Intended bringing home on the head of his son, And he, Forbes, had dismissed the article at a lance, little suspecting the awful sub- Merged interest it held for him, little thinking he was reading about his own father. The truth was stagger- ing, appalling, “After the firat discovery the case has been kept pretty well out of the papers,” said Blunt, “for we didn't want @ premature disclosure of our suspicions. We've been busy tracing the various owners of the Chicago house”"-— He was interrupted by a peremp- tory ring at the hall door. i Forbes wri le and determined It's all right," he said, interpreting the other's look, “I wont't los: head; you may depend on me, It that's Marsland, shall I show him in here?” “Yes, Try and act natural, I don't know what's up, but we may as well be prepared for the worst.” And Mr. Blunt deftly transferred an auto- matic plato! from his hip pocket to the right-hand pocket of his coat, ‘Watch him sharp, Forbes, and Jockey him into walking ahead of you up the hall; don’t let him get behind you for a moment. This is forcing our hand a bit, but we may as well come to a show-down right now, I don't want him to know I'm here un- Ul he enters the room.” Forbes nodded. "What about these?" he asked, hurriediy, point- ing to the letters and loose-ledger leaf on the desk. “Let them stay where they are,” re- Plied Blunt, “Now, then, take your Pipe and @ book, and don't show what you feel. I'l be watching through the crack of this door in case should start something right off, He won't, though.” 80 Forbes, pipe in mouth and book in hand, strolled down the hall as the bell rang for the third time, With an admirable assumption of indifter- ence fh ovened th door and con- fronted John Maraland, Thor h his nerves were well unger contro! Foroes could hardly rep: an exclamation, for Marslund's ins ap: Peurence was powtively AWeaomO; the face, fat and puffy, had @ sort of greenish pallor, the bloodless lips were set in a hard, rigid line, and the Pupils of the congested eyes were so jormously enlarged as to fill the iri He spoke thickly and with evi- dent difficulty. “Good evening, Mr. Forbes.” ‘Good evening, sir.” “May I see you a moment?” Forbes nodded, stepping aside and closing the door as the other entered. “Straight ahead, Mr. Marsland. In the Mbrary, if you please, at the end of the hall.” “He remained in the rear, forcing the other to precede him; and he noticed that Marsland walked stoop-shouldered and slowly, like an old, old man. Mr, Blunt, both hands thrust care- lessly into his coat pockets, stood leaning against the mantelpiece when Maréland entered the room; their eyes met for a long moment, while « tense, perfect silence reigned. Then Marsland, with a tw sed sort of smile and a little shrug, turned away, “I didn’t know you'd company, Mr, Forbes," he said calmly, "but perhaps it's just as we Yes, Just as well,” He was now standing by the des! and his roving eyes fell on the letters and the loose-ledger leaf, so apparent even to the casual glance; a tremor seemed to shoot through him and the Pupils of his eyes dilated, If possible, further, Slowly, as if yielding to a horrible fascination, a superior will power, he put forth a trembl and pickéd up the “sulctde’ then in the same slow, numb manner he lifted the ledger leaf with its star- ing black finger prints, After a long, silent contemplation he lifted his hunted eyes, turning them from Blunt to Forbes and back again; his lips moved, but no sound issyed forth. Blunt was watohing him, as a hawk watches the struggles of a fleld rat, “L think, Mr, Marsland,” he said matter-of-faotly at length, “you've seen that ledger leaf before, You may remember an agent showing you some samples the other day. It's all of fif- teen years, however, since you made those other finger prints, Those ar- tistic blots proved rather an unfor- tunate inspiration, for you left, at the same time, the print of your dexter rhumb and forefinger. You can see that for yourself, ‘There's the 1 tying glass 1f you wish to the two; headquarters, howeve' quite satisfied that the one person made both.” ‘The greenish pallor changed to a motued gray as Marsland replaced the papers on the desk; he made a weary gosture of resignation and dropped into a chair, “All very clever of you, Mr. Blunt, pnp Vt admit” he said, with an effor “but quite unnecessary, Quite unn: essary. You needn't put me through any third degree, any of your stage tricks; Im all in, afd Lt know it, 1 know as well as you that I've been shadowed for the past week, | sus- pected you were on the scent and might get me in the long run, for you're @ capable bloodhound, Mr, Blunt; very capable, I'm sure til) I might have given you @ lot of trou ble; proving your case wouldn't have been easy. But what's the use? can't etand tt any longer, and | eam here to-night to confess to Mr, Forbes, though, I suppose,” glancing at the letters, "you've saved me that trou- ble.” B) ‘nt nodded; the “bloodhound” ex- sion had ieft his face, and with it attitude of xpe yo he pr the removed his hands froin his pockeis, and s down, "Yo he sald grave ly, “I've saved you that trouble, Mr. Marland.” Marsland made another weary ges- ture. He spoke with increasing dift- ficulty. “The game's up and my race is about run, I've got something tho matter with me that nothing can cure—never mind what it is. It's occurred to me I should make what- ever reparation possible, and so I've written the Chicago Second National, telling them the truth about Robert Forbes. It'll be in all the papers to morrow, I suppose. I wish IT could have kept this from my daughter” His voice faltered a moment, then grew stronger. “That's impossible, however, if justice Is to be done. She'll live to curse my name, but, of course, that’s part of the pun ment; ‘I'm not kicking and am ready to take my medicine; every drop of it. “Another thing, Forbes, before I go That — twenty-thousand-dollar k you got Is from me personally; not a cent of it's Muller's. It repre- sents my total interest in the Empire Company, There's no reason why Sol Muller should suffer for my misdeeds. For you were right; I knew the Ster- ling Company must be more or less of a swindle and had met Hammers- ly years He offered me 25 per cent. of whatever I could induce you, or any other greenhorn, to Invest; [ needed the money and thought you were rich enough not to mind if you ever found out. Besides, I'd then be your father-in-law and you couldn't very well do anything. You fooled me completely about your financial standing, and, perhaps, quite unin- tentionally, I'll admit. At all events, I needed a rich son-in-law, of course, when I discovered your pov- erty and true identity the connection became impoanibl “Now I'll tell you about your father if you care to listen; 1 must get it off my mind, tell it to somebody, | needn't go into any other part of my past, for I daresay Mr, Blunt ean oblige you with all details.” Marsland straightened up with an effort, biting his bloodless lips “Don't Interrupt, please, for I find difficulty in talking.” CHAPTER XVII. John Marsland's Statement. “ © begin with,” said Mars- | land, “fifteen years ago I knew Robert Forbes; not intimately, you understand, but enough to know where he lived and to gather some- thing about his private life, For in- stance, I knew he was married, bad one child, and was expecting another. I lived in the same neighborhood, if not the same street, and all this I didn’t uecessarily learn from Forbes himself, His wife didn’t know me— though I knew her by sight—and I never went out with Forbes any- where. We were simply friendly busi- ness acquaintances “Well, @ day came when I needed money badly; I needn't go into the why and the wherefore of It. Enough that I needed money, and for some time had been thinking how I could best help myself to some of the bank's funds. Being a depositor and friendly with Forbes, [ waa familiar with the bank and all pertaining to tt; for in- stance, | knew on what days It had the heaviest deposits, where the wires of the burglar alarm were situated, when the night watchman made his rounds, bie habits and peculiarities; ved In Chicago, was a depositor in the Second National, and therefore for instance, I knew he was an old man and could neither hear nor see too well. I made it m, business to find out all this with INE sUss y picion, And in th a, L might add, the Second National wasn't the great institution it nov is. “On the night tn question, I met Forbes, apparently by accident, on his way home from the bank. I knew the nights when he worked late and he carried the keys the place. Also that generally he passed through my atreet on his way to and fom the subway station, “Well, this night T was waiting for him. Making the excu: if wanted to speak about the renewal of a note soon due, L asked him to step into my house for a moment; al- ways obliging and friendly, he con- sented readily, It was dark, late, and ho one saw him enter—or, at least, they failed to recognize him.” Mae land paused and wiped the sweat from his pallid face. “L was a desperate mai knows I didn’t mean murd: tinued in a low voice. to force the combinat . Ue him up, rob the bank and skip to 4 place where they couldn't extradite me, I lived alone. My wife was dead, and my daughter, then five yeara old, was staying with her aunt in New York, There were no servants in the house, and I was absolutely alone with Forbes.” Marsland was speak- ing slower and slower, pausing be- tween each word. ‘ll save you and myself the de- tails; enough that Forbes proved far more stubborn than I'd expected, ro- fusing to reveal the combination, I was in for it now; I couldn't go back, had exposed my hand and must see the thing through at all costs. I w desperate, and my temper, never very good, was aroused. [ tried harsher methods and I wrung the secret from him at last, but—but he died on my hands"——— “You fiend! You tortured him to death!" The cry was wrung from young Forbes as he sprang at the other with distorted features and clenched hands. Blunt stuck out an iron arm and barred the boy's way. Marsland had not flinched; he sat with closed eyes and bowed head. “Don't think I'm finding any pleas- ure in this recital,” he sald in a mon- otone, have passed over that part, If possible, and I haven't en- larged on it. Let me finish; there isn’t much more to tell.” Young Forbes mastered his emotion with an effort, and, fumbling for a chair, sat down in a dazed manner. “After the—the accident,” pursued Marsland, “I realized I was in for it unless I used my wits, I sat down, thought the whole situation over care- fully, and slowly the plan I eventually followed occurred to me. It was my one chance, and I took It. “Robbing the bank had now become more imperative than ever, and I pro: coeded to dress myself ‘in Forbes’ clothes and to make myself resemble him as much as possible. At that time we were much of a sige, both of us fair-haired and clean shaven. I real- ized that boldness was the best policy. T posseused the keys and combination, knew the plan of the bank thorough! and determined to walk right in, take my chance on not meeting the watch- man, or, in the subdued light, my chance of pretending I was Forbes. His presence would arouse no suspicion, and I could say I had returned to place some valuable papers in the vault or had forgotten something, I re- lied on the watchman’s age, my know- ledge of his impaired aight and hear- ing, to see me through if we met and my knowledge of his habits to obviate such a meeting. “Accordingly, L locked up the house and went boldly to the bank, waiting until | knew the watchman would be making his rounds in a distant part of the building. 1 was wearing Forbes’ light gray ulster and gray slouch hat, and, passing the corner policeman, bi greeted me as Forbes. This was a go! augury, and [ boldly entered the bank, It was ‘now almost midnight “The rest proved ridiculously easy; in thone days the Second National had no time lock on its safe, and, posseas- ing the combination, 1 opened it with- out trouble, helped ‘myself to all the available paper currency, and packed it in @ satchel taken ‘from under Forbes's window, 1 didn’t meet the Watchman until about to leave; he appeared in the low hall as I was about to lock the outer doors, Speak- injy as much like Forbes as C knew how, | greeted him by name and he replied in kind, plainly thinking me the cashier, I returned to the ho satisfied that the first part of my dif- ficult programme had been a. pro- nounced success. It gave me renewed confidence and courage “For the next fort was busily engaged in removing all traces of my crime and in making preparations for a trip abroad, I saw the agents of the house and took five years’ lease in order to obviate discovery of its secret, I also em- ployed part of my time tn composing and writing those letters,” his sombre turning tothe oneson the desk. "They weren't thought out in @ min ute, and [ wished to get the whole thing off my mind as soon as pos- sible. I took the precaution of writ- ing them on different brands of paper. Forbes's wallet contained specimens of the penmanship and also informa- tion which gave me a more complete knowledge of his private life—person- al letters and such. His writing was sy to imitate, and you know,” turn- Mr. Blunt with @ grim smile, “I've always been rather gifted that wa. “The rest you know; I locked up the house, sailed for Europe, remained there six months or so, and matled the letters from different cit “On my return I lived at the Chi- cago address for a few years, then sublet the place until my_lease ran out moved to New York with my daughter and her aunt, That seventy-five thousand had given me but God he con- ight hours I a fresiy start, and, eventually, enabled me to )uy an interest in the Empire Compaay. If you should find a scrap of amber in a snowdrift— And if you should find it was the clue to a terrible You would find yourself in the same odd position THE SECRET IN THE SNOW By MILDRED VAN INWEGEN Next Week’s Complete Novel in The Evening World This is not quite like any other “love-and-mystery” It ii more than worth your “The mistake of leaving my finger= Prints [ was quite unaware of until to-night. As for the discovery in the cellar of the Chicago house, that was &n accident I could not foresee. It Wouldn't have been unearthed for rhaps fifty years or more if hicago subway people hadn't pitel om that particular site for their new ldop and station; otherwise the house wouldn't have been demo ished.” Marsland’s voice had sunk to a hardly perceptible whisper, “That's all,” he said. “Now let the law take Its course, [ am willing.” A ‘spasm passed over his face, eyes closed, and with @ sigh he fel back, breathing heavily and wit! every muscle relaxed. In another mo- ment he had lost consciousness, “Gall Blu the nearest doctor,” sald in a low voice, bending over rostrate man, “You know the rhood better than L. But I'm afraid it's nd use, He's polsoned him- self—atropine, maybe, He must have taken a dose before coming here, Well, perhaps it's best, after all.” A ‘few hours later John Marsland died without regaining consciousness, He had made his last earthly state- ment, later, James Blunt, ja reply to Forbes's question, gave his side of the strange and sensational case, “At the time of advocating the ‘holdup’ I was by no means sure of John Marsland’s guilt; [ mean in ret- erence to your father,” he said. “The Chicago house had changed tenants so frequently during past Stern years that it took time and trou to establish the fact that the eT who had occupied It at the time of your father’s supposed theft was this John Marsiand. ‘ “My acquaintance with him began twenty years ago, when ‘he was ar- rested in Indianapolis for forgery; I was instrumental in bringing it home. to him, but through a technicality he succeeded in beating the case. Thus ‘he had feason to know me and'I htm, His early life had been none too good; his wife had been separated from Mim before she died, and that. was the rea- son—at the time of the Second Na- tional Bank affair—his child was itv. ing in New York with her aunt. I suppose, after his sudden affluence nd a promise to turn over a new leaf, they got together again. ever, after the forgery business in Indianapolis, Maraland ere keep within the law, and I | track of him until finding him the Press dent-manager of the Empire Com- Dany. “Perhaps what first set me think! about him in connection with pend father was his hatred for you; it was entirely unreasonable to suppose that & man of his evigient standing and po- sition would uch measures, go to such extremes simply because yo had accused his daughter and himself of decelt and hypocrisy. Even his part in the Sterling Mines Compan; swindle could not explain it. It at me there must be another and ine finitely greater reason, and yoeg 1 learned that a John Marsland \- cupled the Chicago house fifteen aKo, and had been a depositor tk the. econd National, it set j all the harder, = ee “When at length we succeeded 1: proving beyond doubt that the presle dent of the Empire Campany had 4 tenant of the Chicago house ate time of Forbes's supposed theft and disappearance, I felt I'd hit on the right track, more espect on digging into Marsiand's past, I dis- covered he'd gone to Europe for oix months immediately after the rob- bery. T knew, of course, hia ability with the pen, and that the forging of such @ hand as your fathers wo be quite in Marsiand’s line and pilelty itself, What I learned from Wie letters you know. “There is no doubt,” concluded Blunt, “that Marsland, as he Claimed. could bave given us @ lot of trouble if he'd engaged a sharp lawyer and fought the case to the bitter end. I doubt if we could have hung it om him, even though proving him the author of those letters; for {t's quite impossible to prove the remains those of Robert Forbes, Of course we know they are, but the law demands eon- clusive proof. Lacking that identi. fication the case would fall to pieces, 1 think, for we could ngt show a moe tive. That's why no steps were for Marsland’s arrest. losing his nerve under the strati I wanted to give him ences okt to hang himself, I counted on a vole untary confession or on forcing oné from him by springing these finger- brints—'stage tricks’ as he called tt.” It was characteristic of Forbes that forgetting for the moment his own reat happl his thoughts should turn to the Innocent ones who wore left behind to bear th land's guilt, siveiah of aaa “This will be awful for M ‘are. land!" he exclaimed. “What can be done, Blunt? Can't we keep it from her? Keep it out of the papers?” _ The other shook his head. “How? Your father'y memory can only be vindicated through publicity. Any- way, I believe Marsland spoke the truth when he said he'd written all the facts to the Chicago bank. And you simply can't keep such a. thi Quiet; the facts are bound to,come out. I know how you feel, but that's the worst of such cases—that the in- ocent must suffer for the guilty, There's no way out, Forbes; {t will be on the first page of every morning paper.” The former Dorothy Marsland is now Mrs. Adolph Bergstrom, being married the day Forbes and hia wife, nee Willoughby, returned from thelr noneymoon, Kor Mr, Morris Levy, on reading the sensational news pertain- ing to his defunct, prospective father- in-law, broke the engagement in the prompt and cold-blooded manner of which Dorothy herself had once been guilty; thus at last Bergstrom's pe tence and fidelity were rewarded. They say he has not repented of the step, and those who knew hig wife tn the old days observe she has changed greauly foil the better, | (The End.)