The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, April 9, 1905, Page 5

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

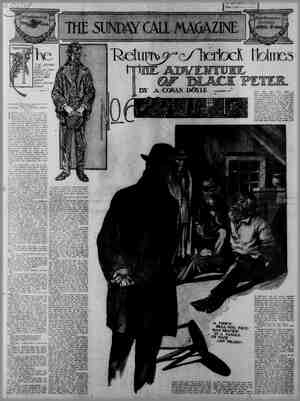

6 ’fi St ‘.l )4 3 2 { ¥ " \ \ b Y, CHAPTER XXIIIL The Devil's Deal. s he tovk the two missives the girl ed him Gordon caught his breath, for one he saw was directed in Anna- Lel's hand. For a moment a hope that vverleaped all his suffering rose in his ain. Had those months wrought a change m her? Had she, too, thought Of their child? Had the cry he voiced on the packet that bore him from Eng- land struck an answering chord in her? He opened its cover. An in- closure dropp@ out, He picked it up blankly. It was the note he had penciled on the channel, returned unopened. The sudden revulsion chilled him. He broke the seal of the second letter and fead—read while a look of utter sick Whiteness crept across his face, a look of rage and suffering that marked every feature. It was from his sister, a letter writ- ten with fingers that sofled and creased it in their agony, blotted and stained with tears. For the thing it told of was a dreadful thing, a whispered charge against him so damning, so sa- in its cruelty, that though lip murmur it to a gloating ear, yet pen refused to word it. The whole thing turned black before him, and the dusk seemed shot through with barbed and faming javelins of agony. He crushed the letter in his hand, and, with a gesture like a madman’s, thrust it into Shelley’s, turning to him a countenance distorted with passion, gauche, malignant, repulsive. “Read it, Shelley,” he said in a stran- gled voice “Read it and know Lon- don, the most ineffable centaur ever begotten of hypocrisy and a night- mare! Read what its wretched lepers are saying! There is a place in Michael meelo’s ‘Last Judgment’ in/ the Sistine apcl that was made for their kind, { may the like await them in that Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ— this fearful Iimprecation he ay from their startled faces vineyard lane, on into the t to a sense of direction, to ing save the blackness in his The night fell, odorous with grape- and the moon stained the ter- < amber. It shone on Gordon as he sat by the little wharf where the gkiff rocked in the ripples, his eye viewless, looking straight before him across the lake. For him there was no sanctuary in time or in distance. The passage he read Newstead Abbey in his her’s open Bi beside her body, ashed-through his mind: “And among these nations shalt thou find no ease, er shall the sole of thy foot have ; . In the morning thou shalt say, Would God it were even! and at even theu shalt say, Would God it were rning!” He had found—should find— n e nor rest! The captive of Chil- Jon had been bound only with fetters of on to stone pillars. He was chained - links of hate to the freezing e world’s contumely! »otsteps went along the ley's voice spoke oon, and we must comfort came distinctly as the 1wont stood near him, her ling into his, fringed with in- daring. id; “‘they are . They hated me, came quite close to him. d we care? What are they s the Jane of the Drury Lane oom he saw now-—the Jane brilliance and wit had held him but there was something 1 her look than he had nver before a recklessness, an invi- nd an assent. he exclaimed. She touched his hand. “Why should we stay re? Let us go away from where they cannot follow us leeper to sting Gordon stared at her, his eyes hold- ing hers. To go away—with her? To slip the leash of all that was pagan in him? What matter? He was damned y—a social pariah; why strive to undeserve the reputation? His thought was rling through savage s of vindictive wrath, cling like a maelstrom, one dead center: Civiliza- n off. Henceforth his s to live to himself, for his own ends, the savage, as the beast of the field. To live and to die, knowing that no greater agony that was meted to h'm now could await him, even in that nethermest reach where the lost are driven at the end. “We must comfort him if we can!” The words Shelley had spoken seemed to vibrate in the stillness like the caught key of an organ. He turned to where- Villa Diodati above them slept in the long arms of the night shadows, listening to the con- tending voices within him. Comfort? The placid comfort of philosophy for him whose flesh was fever and his blood quicksilver? In this girl life and action beckoned to him—Ilife full and abundant—forgetfulness, win- dering and pleasure, fleeting surely, but still his while it should last! And yet— The girl's hand was on the skiff. On a sudden a cry of fear burst from her lips and she shrank back as a disordered figure broke from the darkness and clutched Gordon’s arm fiercely. “Where are you taking her now?” Gordon’s thought veered. In his numbness of feeling there scarce seemed strangeness in the apparition. As he looked at the Oriental, mus- tachioed face, haggard and haunted, his 1ips rather than his mind replied: “Who knows?” “You lie! You ruined her career and stole her away from London and from me! Now you want to take her from these last friends of hers—for yourself! But you cannot go where I will pot find you! And where you go the world shall know and despise you!” Jane’s eyes flashed upon the speak- er. “You!” she cried in contemptu- ous anger. “You hated him evén in London: now you have followed him here. It is you who have set the peasants to spy upon us! It is you who have spread tales through Gen- eva! You whose lies Sent the syndic to-day!” Gordon had been staring at the Moorish, ¥theatric face with a gaze of singular inqguiry, his brain searching, searching for a lost clew, All at once the haze lightened. His thoughts jeaped across a chasm of time. He saw a reckless youth, a deserter from the navy, whom he had befriended in Greece—a youth who had vanished suddenly from Missolonghi during the feast of Ramazan. He saw a sham- bling, cactus- bordered road to the seashore—a file, of Turkish soldiers, the foremost in a purple coat and about t tion had life wz carrying a long wand—a beast of bur- bearing a_ brown sack: "Trevanion!” he said. ‘Trevanion He burst into a laugh, re-echoing, sardenic, a laugh now of absolute, re- morseless unconcern, of crude reck- lessness flaunting at last supréme over crumpled resolve—the laugh of a zeal- ot tlagellant beneath the lash, a de- risive Villon on the scaffold. “So I stole her from you! You, even you, dare to accuse me. Out of my sight!” he sald and -flung him roughly from the path. Gordon held out his hand to Jane Clermont, lifted her into the skiff and, springing in, sent the slim cockle- shell shooting out into the still ex- panse like an arrow on the air. Then he took un the oars and turned its prow down the lake to where the streaming lights of the careless city wavered through the mists, pale green under the moon- beams. The journal which Gordon had hurled from him lay in the vine rows next morning when Shelley, with a face of trouble and foreboding, passed along the dewy lane. He read the words written on its cover: ““And all our yesterdays have light- ed fools the way to dusty death. I will keep no record of that same hes- ternal torchlight; and to prevent me from returning, like a dog, to the vomit of memory, I throw away this volume and write in Ipecacuapha: Hang up justice! Aet morality go beg! To be sure, 1 have long de- spised myself and man, but I never spat in the face of my species before —'O fool! I shall go,mad! ” CHAPTER XXIV. The Mark of the Beast. ‘“Your coffee, my lord?"” 1t was Fletcher’'s usual inquiry, rée peated night and morning—the same words that on the Ostend packet had tcld his master that his wanderings were shared. After these many months in Venice, where George Gordon had shut upon his retreat the floodgates of the world, the old servant’s tone had the same wistful cadence of solicitude. Time for Gordon had passed like wreckage running with the tide. The few feverad weeks of wandering through Switzerland with Jane Cler- mont—he scarcely knew where or how they had ended—had left in his mind only a series of phantom impressions; woods of withered pine, Alpine glaciers shining like truth, Wengen torrents like talls of white horses and distant thunder of avalanches, as if God were peiting the devil down from heaven with snowballe. And neither the pip- ing of the shepherd, nor the rumble of the storm, nor the torrent, the moun- tain, the glacier, the forest or the cioud, had lighted the darkness of his heart or enabled him to lose his wretched identity in the power and the glory above and beneath him. At Ttome his numbed senses awak- ened and he found himself alone, and around him his humankind which he hated, spying tourists and scribble who sharpened their scavenger penc! 1o record his vagaries. He fled from then to Venice, whers, thanks to re- port, Fletcher had found his masger. But it was a changed Gordon who had ensconced himself here—a Gordon to whoin social convention had become a sneer and the praise or blame of his fellows 1die chaif cast in the wind. He ate and drank and slept—not as other men, but as a gormand and debauche. Such let as he wrote—to his sister, to Tom Moore, to Hobhouse—were flip- pant mockeries. Rarely was he seen at opera, at ridotto, at vonversazione. When he went abroad it was most often by night, as though he shunned «he daylight. More than one cabaret in the shadow of the Palace of the Doges knew the white satiric face that stared out from its terrace over the waterway re covered gondolas crept like black spiders, till the clock of St. Mark’s struck the third hour of the morning. And more than one black and red sashed boatman whispered tales of the Palazzo Mocenigo on the Grand Canal and the “Giovannotto Inglese who spent great sums.” The gondolieri turned their heads to gaze as thev sculled past the. carved gateway. Did not the priests call him “the wicked milord?” And did not all i v of Marianna, the linen- E ife of the street Spezieria, and of Margarita Cogni, the black-eyed Fornarina, who came and went as she pleased in the milord's household? They themselves had gained many a coin by telling these tales to the tourists from milord’s own ceuntry, who came to watch from across the canal with opera-glasses, a8 if he were a ravenous beast or a raree-show; who lay in wait at nightfall to see his gon- dola pass to the wide outlying lagoon, haunted the sandspit of the Lido where he rode horseback, and offered bribes to his servants to see the bed wherein he slept. They took the tourists’ soldi shamefacedly, however, for they knew other tales, too: how he had fupnished money to send Beppo, the son of the fruit peddler, to the art school at Naples; how he had given fifty louis d'or to rebuild the burned shop of the printer of Sanp Samuele. “Your coffee, my lord?” Fletcher re- peated the inquiry, for his master had not heard. “No; bring some cognac, Fletcher.” Even in the warm blaze Gordon shivered. Ghosts had troubled him this day. Ghosts that stalked through the confused mist and rose before him in the throngs that passed and re- passed before his mind's eye. Ghosts whose diverse countenances resolved themselves, like phantasmagoria, into a single one—the pained eager face of Shelley- The recurring sensation had brought a sick sense of awakening, as of something buried that stirred in its submerged chrysalis, protesting against the silt settling upon it. But brandy had lost its power to lay those ghosts. He went to the desk which held the black phial, the tiny glass comforter to which he resorted more and more often. Once with its surcease it had brought a splendor and plenitude of power; of late its-relief had been lent at the price of distorted visions. As he drew out the thin-walled drawer, its worm-eaten bottom col- lapsed and its jumble of contents poured down on the mahogany- He paused, his hand outstretched. Atop of the melange lay a silver-set miniature. nearer the light. A girl's face, hued like a hyacinth, looked out of his palm, painted on ivory. A string of pearls was about her neck. For an instant he regarded the min- jature fixedly, his recollection traveling far. he had found in the capsized boat at Villa Diodati! He had purposed send- ing it after the two strangers. The events of that wild night had effaced the incident from his mind,. as a wet sponge wipes off a slate. Fletcher, finding the oval long ago in a poket lining, had put in the desk drawer for safe keeping, where until this moment it had not met his master’s eye. He picked it up, holding it | The pearls aided. It was the one| “Teresa.” Gordon suddenly remem- bered the name perfectly. With the memory mixed a sardonic reflection; the man who had lost the miniature that day in Switzerland had hastened away with clothing scarcely dried. Well, if that brother had deemed him- self too good to linger with the outcast, the balance had been squared. The sister, perforee, had made a longer stay! » Holding 'it, he walked to a folded mirror in a corner of the wall and opened its panels. There had been a time when he had sald no appetite should ever rule him; the face he saw reflected now wore the lines of in- corrigible self-indulgence, animalism, the sinister badge of the bacchanal. “Is that you, George Gordon?” he asked. The ghosts drew nearer. They peered over his shoulders. He felt their grasping at him. He cursed them. By what right did they follow him? By what damnable chance, ruled by what infernal jugglery, came this painted semblance to open old tombs? Some- thing had awakened in him—it was the side that recollected, remorseless and impenitent, but no longer benumbed, writhing with smarting vitality. Awake, it recoiled abashed from the voiceless vade retro of that .symibol. What part had he im that pur- ity whose visible emblem mocked and derided him? What comrade- ship did life hold for him save the hideous Gorgon of memory, the Cerberus of ill fame, spirits of the dark, garish fellows of the half-world— “they whose steps go down to hell!” A fury, demoniac, terrible, fell on him. He seized the miniature, dashed it on.the floor, stamped it with his heel and crushed and ground it into indis- guishable fragments. Then he sprangiup, and with an oath whose note was echoed by the tame raven croaking on.the landing rushed down the stairway and threw himself into his gendola. The moon rose red as a house afire. Before it paled, he had passed the la- goon. In the dim light that presaged the sodden dawn he leaped ashore on the mainland, pierced the damp laurel thickets that skirted the river Brenta and plunged into the forest. CHAPTER XXV. Teresa Meets a Stranger. Through the twittering dawn, with its multitudinous damp scents, its stubble fields of maize glimpsed through the stripped ilex trees, whose twigs scrawled black hieroglyphics on the hueless sky, Gordon strode sharply, heedless of direction. % The convulsion of rage with which he had destroyed the miniature had finished the work the latter's advent had begun. The nerve, stirring from its opiate sleep to a consciousnéss of dull pain, had jarred itself to agony. His mind was awake, but the wind had swept saltly through the coverts of his passiop, and their denizens crouched shivering. The sight of a dove-tinted villa guarded by cypress spears—a gray gathering of cupolas—told him he had walked about two miles. This was La Mira, one of the estates of the Countess Albrizzi, a great name in Venice, He turned aside into the de- serted olive grove above the river. A slim walk meandered here, thick with dead leaves, with a cleared slope stretching down to where the deep-eyed Brenta twisted like a drenched ribbon on its way to the salt marshes. Front- ing this breach, Gordon came abruptly upon a wooden shrine, with a weather-fretted prayer bench. He stopped, regarding it half-ab- sently, his surcharged thought year- ranging disused images out of some dusty speculative storehouse. A more magniticent shrine rose on every campo of Venice. They stood for a priestly hierarchy, an elaborate clericalism— the mullioned worship that to his life seemed only the variform expression of the futile earth-want, the satiric hallucination of finite and mortal brain that grasped at immortality and the infinite. “This, set in the isolation of the place, seemed a symbol of more primitive faith and prayer, of religion rcugh-hewn, shorn of its formal acces- sories. N He went a step nearer, seeing a small book lying beside the prayer bench. He picked it up. It was a reprint in £ng- lish of his own “Prisoner of Chillon,” from a local press in Padua. A sense of incongruity smote him. It was the poem he had composed in Geneva. He readily surmised that it was - through Shelley the verses had reached his publisher in England, to meet his eye a year afterward, in a foreign dress, in an Italian forest. He turned the pages curlously, con- ning the scarce remembered stanzas. Coyld he himself have created them? The instant wonder passed, blotted out by lines he saw penned on the fly-leaf— lines that he read with a tightening at his heart and an electric-like rush of strange sensations such as he had never felt. For what was written there, in the delicate tracery of a fem- inine hand, and in phrases simple and pure as only the secrgt heart of a girl couid have framed them, was a prayer: *“Obh, my God! Graciously hear me. I take encouragement from the assur- ance of Thy word to pray to Thee in behalf of the author of this book which has so pleased me. Thou desirest not the death of a sinner—save, therefore, him whom Venice calls (‘the wicked milord.” Thou, who by sin art offended and by penance satisfied, give to him the desire to return to the good and to glorify the talents Thou has so richly shis face. béstowed upon him. And grant that the punishment his evil behayvior has already brought him be more than suf- ficient to cover his guilt from Thine eyes. \ “On_blessed Virgin, Queen of the most holy Rosary! Intercede and ob- tain for me of thy Son our Lord this grace! Amen.” % b, A step fell behind him. He turned half-dazed, his mind full of conflict. A girl stood near him, delicate and alert and wand-like as a golden wil- low, her curling amber hair loosely caught, her sea-blue eyes wide and a little startled. She wore a Venetian hood, out of whose green sheath her face looked, like lilies under leaves. Gordon's mind came back to the pres- ent time and space across an illimita- bie distance. He stared, half believing himself in some automatic hallucination. There had been no time to speculate upon what manner of hand had written those words, what manner of woman's soul had so weirdly touched his own out of the void. Knowledge came stag- geringly. Hers was the face of the miniature that his heel had crushed to powder. He noted that her eyes had fallen to the book in his hand, as mechanically he asked, in Italian: ““This book is yours, Signorina?” “Yes.” There was a faint flush of color in her cheek, for she saw the volumé was open at the written page. “If there be-an ear which is open to human appeal,” he added gently, “that prayer was registered, I know!"” “If there be!” er thought stirred protestingly. “Ah, Signore, 'surely there is. some one who hears! ~How could one live and pray otherwise?” The girl caught the mixed feeling in He was not Itallan—his ac- cent had told her that. He was an Englishman, too, perhaps. “Do you know him, Signore?” His head turned-quickly toward her. In truth, had he ever.really known himself? “Yes,” he answered after a pause. “I know him, Signorina—far better than most of the world.” She hésitated, opening and closing the book in her hands. “Is he all they say of him?"” “Who knows,' Signorina?” It was an involuntary exclamation that ‘sounded like acquiescence. The girl’s face fell. In her thought, the man of her dreaming, lacking an open ad- vocate, had gained the secret one of sympathy. Was it all true then? Her voice faltered a little. “I have not believed, Signore, that with a heart all evil one could write— so!"” Into the raw blend of tangent emo- tions which were enwrapping Gordon, had entered, as she spoke, another well-defined. Never in his life, for his own sake, had he cared whether one or many believed truth or lie of him. But mow there thrilled in him, new- born. a desire that this slight girl should not judge him as did the world. The feeling lent his words a curious energy: “Many tales are told, Signorina, that are true—some that are false. If he were here—and 1 speak from certain knowledge of him—he would not wish me to extenuate; least of all to.you who have written what is on that’'leaf. Perhaps that has been one of his faults, that he has never justified himself. By common report he has committed all crimes, Signorina. He has thought it useless to deny, since slander is not guilt, nor is denial innocence, and since neither good nor bad Treport could lighten or add to his wretchedness.” The tint of her clear eyes deepened. “I knew was wretched. Signore! It was f reason I left -the prayer here oven t before Our Lady of Sor- rows—because. I have heard he is an outcast from his own ‘country and his own people. And then, because of this.” She touched the volume. ‘“‘Ah, I have read iittle of all he has written —this is the only poem—for I read his English tongue so poorly; but in this his heart speaks, Signore. It speaks of pain and suffering and bondage. It was not only the long-ago prisoner he sang of; it was-himself! himself! I felt it—here, like a hurt.” r She had spoken rapidly, stumblingly, and ended with a hand pressed on her heart. Her own feeling, as she sud- denly becamé aware of her vehemence, startled her, and she half turned away, her lips trembling. A softer light suffused her cheek. His- pain-engraved face brought, a mist to her -eyes. She was a child of the sun, with blood leaping to quick response and a heart a well of undiscovered impulses.” The wicked milord’s form lost distinction and faded. Here was a being mysteri- ous, wretched, too, and alone—not in- tangible as was he of the Palazzo Mocenigo, but beside her, speaking with a voice which thrilled everv nerve of her sensitive nature. Unconsciously she drew closer to him. -~ At that moment a call came under the bare boughs: “Teresa! Teresa!" She drew back. “It is La Contessa,” she said; “I must hasten,” and started quickly through the trees. His voice overtook her. The word vibrated. “Will you give me the prayer?” He had come toward her as she stooped. “There is a charm in such things, perhaps.” The voice called agaln, impatiently: “Teresa!” She opened the book and tore out the leaf with uncertain fingers. As he took it his hand met hers. He bent his head and toudhed it with his lips. She flushed deeply, then turned and ‘‘Signorina!” and more The Adventure o BLAC Continued From Page Two. S ke e S R ning. It is very possible if I had known- about this notebook it might have led away my thoughts, as it did yours. But all I heard pointed in the one di- rection. The amazing strength, the skill in the use of the harpoon, the rum and water, the scalskin tobacco-pouch with ' the coarse tobacco—all these pointed to a seaman and one who had been a whalér. I was convinced that the initials ‘P. C."yupon the pouch wére a coincidence and not those of Peter Carey, since he seldom smoked, and no pipe was found in his cabin. You remember that I asked whether whisky and brandy were in the cabin. You sald they were. many landsmen are there who woul@ drink rum when they could get these other spirits? Yes, I was certain it was a seaman.” “And how did you find him?"” “My dear "sir, the nroblem had be- come a very simple one. If it were a ‘seaman it could only be a seaman who had been with him on the Sea Uni- corn. So far as I could learn he had sailed in no other ship. 1 spent three ER days in wiring to Dundee and at the end of that time I had ascertained the nmunu of the crew of the Sea Unicorn | 1883. When ¥ found Patrick Cairns | among the harpooners my 'h was ng its end. I argued that the an was probably in London and that he would desire to leave the country for time. I therefore spent some days in the East End, devised an Arc- tic expedition, put £ tempting Y serve ‘terms for harpooners who would undt:l‘" Captain Basil—and behold the result!” i ‘““Wonderful!"” cried Hopkins. ‘“Won- derful!” “You must obtain the release of young Neligan as soon as e said Holmes. “I confess - I thi you owe him some apology. The T'll send particulars_ (The En .of the Albrizzi - changed the dull convent walls for the () ran through the naked trees toward the villa shielded in its cypress rows. The, girl ran breathlessly to the ter- race, dvhere a lady leaned from a win- dow with a gently chiding tongue: “Do they teach you to do wholly without sleep in convents?” she cried. “Do you not know your father and Count Guiecioli, your lord and master to be, are to arrive to-day from Raven- na? You will be wilted before the evening.” The girl entered the house. Under the olive wood a man, strange- ly moved, a rustling paper still in his hand, walked back with quick strides to his gondola, striving to exorcise a chuckling fiend within him, who, wita mocking and malignant emphasis, kept repeating: “‘Oh, blessed Virgin, Queen of the most holy Rosary! Intercede and ob- tain for me, of Thy Son our Lord, this grace!” . CHAPTER XXVIL A’ Woman of Fire and Dreams. From the moment those lips touched her hand in that meeting at the wood shrine Teresa Gamba felt her life un- fold to rose-veined visions. . Her unmothered childhood and tHe placid convent school years at Bag- nuacavallo, near Ravenna, had known no mystery other than her day-dreams had fashioned. She had dreamed much: of the time when she should marry and redeem the fortunes of her house, which, despite. untainted blood and .ancient provincial name, was impover- ished; of the freedom of Italy, the sole topic, aside from his endless chemical experiments, of which her fdther, now - sTowing feeble, never tired; of her elder brother, away in Wallachia, secretary to tHe Greek Prince Mavrocordato; of the few books she read, and.the fewer people she met. But these dreams had not. vossessed the charm of novelty. Even when, at eighteen, through fam- ily friendship, she became a member household and ex- garlanded La ' Mira—even with those rare days when she saw the gay splen- ‘dor ot Venice from a curtained gondola —even then her mental lfe suffered small change. ‘The. marriage arranged for her with Count Guiccioli, the oldest and richest nobleman of Ravenna, a miser and~ twice a widower, had aroused an inter- est in her mind scarce greater than had the tales of the Englishman of the Palazzo Mocenigo. Such marriages ‘were ‘of common occurrence in the life she knew: the “wicked milord” was a stranger thing—one to speculate more endlessly upon. But that meeting - in the wood Kad turned the course of her imaginings. “A ,wanderer—like him"”; the words had bridged the chasm between the dream- ing and the real. The secret thought given to the ‘“‘wicked milord” f?und itsif absorbed by a nearer object. 'The palazzo on the Grand Canal grew more remote, and the stranger she had Seen stepped at a single stride info a place her mind had already prepared. The blush with which she had taken the book from Gerdon’s hand was one of mere self-consciodSness; the vivid, burning color which overspread her face as she ran back through the trees was something very different. It was a part bf her throbbing heart, of the tremulous confusion. that overran her whole body, called into life by the touch of those palely carved lips upon her fingers. His colorless face—a face with the outline of the Apollo Belve- dere—the gray magnetic eyes, the words he had said and their accent of sadnes§, all were full of suggestive misery. Why was he a wanderer—like that .other? Not for a kindred reasof, surely!, He could not be evil also! Rather. it must have been because of some loss, some hurt of love which time might remedy. Her agile fancy constructed, more than one hypothesis, spun more than one romaaee, all of like ending. A new love would heal his heart. Some time he would look into a woman's eyes— not as he had looked into hers; some one would feel his lips—not as he had kissed her hand. She in the meantime would be no longer*a girl; she would be the Contessa Guiccioli, with a palazzo of her own in Ravenna, and— a husband. But, somehow, this reflection brought no satisfaction. The old Count she had seen. more than once driving by in state when she played as a chjld in the convent woods; and that he with his riches shoull desire her, had given her father great pride, which was re- flected in her. Her suitor had brought his age and ailments to La Mira on the very day she had met the stranger at the shrine—the day her heart had beat so oddly—and wjth his arrival, her marriage had pfojected itself out of the hazy future and become a dire thing of the present. She felt a fresh distaste of his sharp yellow eyes, his cracked laugh. His eighty wiry years seemed as many centuries. She be- came moody, put her father off and took refuge in whims.” The Contessa advised the city, and the week’s end saw the Albrizzi palazzo thrown open. In Venice, Teresa’s spirits rose. She loved to watch the bright little shops opening like morning-glories, the sky- faring pigeons a silver quiver of wings; to lie in_the gondola waiting while her father drank his brandy at the piaz- zeta caffe; to buy figs from little lame Pasquale, who watched for her at a shop-door in a narrow calle near at hand; to see the gaudy flotillas of the carnival, and the wedding processions, fresh from the church, crossing the la- goon to leave their gifts at the various island-convents; or, propelled by Tita’'s swinging oar, to glide slowly in the purpling sunset shadows, by the Plazza San Marco, around red-towered San Glorgio, and so home again on color- soaked canals in the gleaming ruby of the afterglow, through a city bub- ‘bling with ivory domes and glistening like an opal’s heart under its tiara of towers. - She scarcely told the secret to her own heart—that it was one face she looked to see, one mysterious stranger whose image haunted every campo, every balcony and every bridge. She flushed whenever she thought of that kiss on her fingers; in the daytime she felt it there like a sentient thing; at night when she woke, her hand burned her cheek. K ‘Who was he? Why had he asked her for the prayer? What ~ he: done with it? Was he still in +? Should h She wondered, as, parting the gondola tenda, she watched her father cross the pave for his cog- nac. © “Are there many English in Venice, Tita?” ; =2 - The. - A Q 7 { 2 IS g 1%D»a the five-year-old fig-seller was set to watch for her. “He fell from the scaffolding!™ said a voice. “If it should be little Pasquale!" cried Teresa, and springing out, ran quickly forward. Tita waited to se- cure the gondola before he followed her. A sad accident had happened. Be- fore the calle a platform had been erected from “which spectators might watch the flotillas of the carnival Little Pasquale’s delight was a tame sparrow, whose hame was a wicker cage, and climbing to sun his pet when he had been left to tend the empty shop, the child slipped and fallen to the pavement. Teresa broke through the circle of bystanders and knelt by the tumbled little body, looking at the tiny face now so waxen. The neighbors thronged about, stupefied and hindering. A wo- man ran to fetch the mother, gossiping with a neighbor. Another called loud- ly for a priest. The girl, looking up, was bewildered by the tumult. “He must be got in,” she murmured, half helplessly, for the people ringed them round. A voice answered close beside her: “I will carry him, Signorina”—and a form she knew bent beside her, and very gently lifted the small bundle in his arms. Teresa’'s heart bounded. Through these days she had longed to hear that voice again how vainly! Now in this moment she was brought suddenly close $0 him. She ceased to hear the sounds about her—saw only him. She sprang up and led the way through the press, down the close damp calle and to the shop where the child lived. “Dog of the Virgin! He need touch no finger to child of mine!” swore a carpenter from the adjoining campo. “Nor mine! “Why didn’t you carry him in your- self then?” growled Giuseppe, the fruit vender. “Standing there like a bronze pig! What have you against the Eng- lishman? Didn't he buy your brother- in-law a new gondola when the piling smashed it?” “‘Scellerato!” sneered the carpenter. “Why is his face so white? Like a po- tato sprout in a cellar! He is so evil he fears the sun!™ The fruit vender turned away dis- dainfully. His foot kicked a shapeless wicker object—it was little Pasquale’s cage smashed flat. The sparrow inside was gasping. He picked up the cage and carried it to the shop. In the inner, ill-lighted room, Gordon laid ‘the child on a couch. He had spoken no. further word to Teresa. At the first sight of her, kneeling in the street, he had started visibly as he had done in the forest of La Mira when he gnized her face as that of the min- ature. Now he was feeling her pres- ence beside him with a curious thrill not unlike her own—a pleasure deeply mixed with pain that almost a physical pang. Since that dawn walk above the plane-treed Brenta he had been tread- ing strange ways. In the hours that followed, remorse had been born in him. And as the first indrawn breath racks the half-drowndd body with agony greater than that of the death it has already tasted, so the man had suffered. During a fortnight, words written on a sheet of paper that he carried in his pocket had rung through his brain. Day after day, as he sat in his gloomy palazzo, he had heard them; night after night they had float- ed with him as his gondola bore him through the waterways ringing with the estro of the carnival. To escape them he had fled again and again to the black phial, but when he awoke the pain was still with him, instinct and unrenounceable. It was more acute at this moment than it had ever been. Teresa scarcely noted the fruit ven- der as he put the battered cage into her hand just before its feathered oc- cupant breathed its last. Her look, fixed on Gordon, was still eloquent with the surprise. She saw the same pale face, the same deep eyes, the same chiseled curve of lips. His voice, too, as he dispatched the kind-hearted Giluseppe for a surgeon on the Riva, had the same cadence of sadness. She had noticed that his step halted as he walked, as though from weakness. And surely there was illness in his face, too! Had there been any tender hands near him—as tender as those with which he now examined the un- conscious child? As Gordon bent above him little Pas- quale opened his eyes. His gaze fell first not on the man or on Teresa, but on the broken cage beside him. where the bird lay still, one claw standing stiffly upright. He tried to ' lift his head, and called the sparrow’s name. There was no answering chirp. The claw was very still. Then little Pasquale saw the faces about him and knew what had hap- pened. “He's dead!” he shrilled, and burst into tears. CHAPTER XXVIL The Evil Eye. Tears, too, had rushed to Teresa's eyes, with a sweet glad sense of some- thing not akin to griéf. Her hand on the couch in the semi-darkness touch- ed another and she drew it away, trembling. Suddenly a wail came from the calle, @ hurried step crossed the shop floor, and the slattern mother burst into the room. Close behind followed Tita, who, seeing his mistress, blocked the inner door with his huge frame against the curious, with whom the place now overflowed. The weeping woman had thrown herself beside the couch where the child lay, his eyes closed again. All at once she saw-the man who stood before her, and, to Teresa's astonish- ment, sprang up and spat out coarse imprecations. “The evil eye!” she screamed. “Take the Inglese away and fetch some holy water! He has the evil eye!” Teresa saw the spasm of pain that crossed the colorless face. “No, no!” she cried. “What did I say!” sneered the car- penter. Tita’s great hand took him by the throat. “Silence, devout jellyfish!™ he said, “or I crack your skull 't you hear the Signorina?” ‘‘The evil eye!” wailed the woman, flinging back inky hair from her brows. “He looked at the heart of my life or l: would not have fallen!” “For e!” protested Teresa in- dignantly. “He who w him in gihn “twnadh Ah, do not listen!" e turn Gordon appealingly. “She is mad to say such things! Let us go,” she added hastily, as murmurs swelled from the shop. “We can do no more!” “Go, son of the Black One!” scream- ;‘1’ t'he ‘Wwoman. “Go before my child es!™ T ) (Continued Next Sunday.) )