The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, July 17, 1904, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

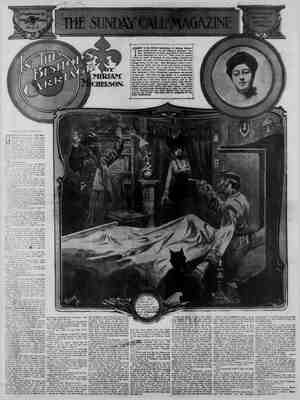

here and listen to such guff? You've been having a high old time, eh, and you never give a thought to me up there! I might ’a’ rotted in that black hole for all you'd care, you—" “Don’t! I did, Tom; I did.” I was shivering at the name, but I couldn’t bear his thinking that way of me. “I went up once, but they wouldn't let me see you. I wrote you, but they sent back the letters. Mag went up, too, but had to come back. And that time I brought you—" My volce trailed off. In that minute I saw myself on the way up to Sing ing with the basket and all of my es and all my schemes for amusing him. And this is what I'd have seen if they'd let me in—this big, gruff, mur- dering beast! Oh, yes—yes—beast is what he s, and it didn’t make him look it less that he believed me and—and began to think of me in a different way. “I thought you wouldn't go back on a feller, Nance. That's why I come aight to you. It was my game to ave you hide me for a day or two, till vou could make a strike somewhere and we'd light out together. How're ve fixed? Pretty smart, eh? You look it, my girl, you look—my eye, Nance, vou lpok good enough to eat, and I'm hungry for you!” Maggie, if I'd had to die for it I couldn’t have moved then. You'd think a man would know when the woman he’s holding in his arms is fainting— sick at the touch of him. A woman would. It wasn't my Tom that I'd known, that I'd worked with and played with and—It was a great brute, whose mouth—who had no eyes, no ears, no senses but—ah! * * ¢ He laughed when I broke away from him at last. He laughed! And I knew I'd have to tell him straight in words. om,” I gasped, “you can have all I've got; and it's plenty to get you out of the way. But—but you can’t have —me—any more. That's—done!” Oh, the beast in his face! It must have looked like that when the guard got his last glimpse of it. “You're kiddin’ me?” he growled. I shook my head. Then he ripped it out. Sald the worst he could and ended with a curse! The blood boiled in me. The old Nance never stood that; she used to sneer at other women who did. “Get out of here!” I cried. “Go—go, Tom Dorgan. I'll send every cent I've ot to you to Mother Douty’s within » hours, but don’'t you dare—" Don’t you dare, you she-devil! Just 1ake up your mind to drop these new- gled airs, and mighty quick. I tell ou you'll come with me "cause I need u and I want you, and I want you now. And I'll keep you when once I get you again. We'll hang together. No more o' this one-sided lay-out for me, where you get all the soft and it's me for the hard. You belong to me. Y you do. Just think back a bit, Nance Olden, and remember the kind of customer I am. If you've forgot, just let me remind you that what I know would put you behind bars, my lady, and it shall, I swear, if I've got to go to the Chair for it!” Tom! It was Tom talking that way to me. I couldn’t bear it. I miade a rush for the door. He got there, too, and catching me by the shoulder, he lifted his fist. But it never fell, Mag. I think I could kill a man who struck me. But just as I shut my eyes and shivered away from him, while I waited for the blow, a knock came to the door and Fred Obermuller walked in. “Eh? Oh! Excuse me. I didn’t know there was anybody else. Nance, your face is ghastly. . . . What’s up?” he said sharply. He looked from me to Tom—Tom, standing off there ready to spring on him, to dart past him, to fly out of the window—ready for anything; only waiting to know what the thing was to be. My senses came back to me then. The sight of Obermuller, with those keen, quick eyes behind his glasses, his strong, square chin, and the whole poise of his head and body that makes men wait to hear what he has to say; the knowledge that that man was my friend, mine—Nancy Olden’s—lifted me out of the mud I'd sunk back in, and put my feet again on a Jevel with his. “Tom,” I sald slowly, “Mr. Ober- muller is & friend of mine. No—listen! What we've been talking about is set- tled. Don’t bring it up again. It doesn’t interest him and it can’t change me; I swear to you, it can't; nothing can. I'm going to ask Mr. Obermuller to help you without telling him just what the scrape is, and—and I'm going to be sure that he'll do it just because he—" “Because you've taken up with him, have you?” Tom shouted savagely. “Because she’s your—" “Tom!” I cried. “Tom — oh, yes, now I remember.” Obermuller got betwen us as he spoke. “Your friend up—in the country that you went to see and couldn’'t. Not a very good looker, your friend, Nance. But—farming, I suppose, Mr.—Tom?— plays the deuce with one's looks. And another thing it does: it makes 2 man forget sometimes just how to behave in town. I'll be charmed, Mr. Tom, to oblige a friend of Miss Olden’s; but I must insist that he does not talk like a—farmer.” He was quite close to Tom when he finished, and Tom was glaring up at him. And, Mag, I didn’t know which one I was most afraid for. Don’t you look at me that way, Mag Monahan, and don’t you dare to guess anything! “If you think,” growled Tom, “that I'm going to let you get off with the girl, you're mighty—" “Now, I've told you not to say that. The reason I'll do the thing she’s going to ask of me—if it's what I think it is— is because this girl's a plucky little creature with a soul big enough to lift her out of the muck you probably helped her into. It's because she's got brains, talent, and a heart. It's because THE SAN FRANCISCO SUNDAY CALL In The Sunday Call, July 24th, Begins a New Series of the Famous Articles by Finley Peter Dunne MR. DOOLE Whose pungent humor and political satires have pever failed to convulse the entire country with laughter. @nd will appear every Sunday after July 24 until completed. —well, it's because I feel like it, and she deserves a friend.” “You dong know what she is.” was a snarl from Tom. “You don’t—" “Oh, yes I do; you cur! I know what she was, too. And I even know what she will be; but that doesn’t concern you.” “The hell it don’t!"” Obermuller turned his back on him. I was dumb and still. Tom Dorgan had struck me after all. “What is it you want me Nance?” Obermuller asked. “Get him away on a steamer—quick,"” I murmured—I couldn’t look him in the face—"without asking why, or what his name is.” He turned to Tom. “Well?” “I won't go—not without her.” “Because you're so fond of her, eh? So fond, your first thought on quitting the—country was to come here to get her in trouble. If you've been traced—' “Ah! You wouldn’t like that, eh?” sneered Tom. “Would you?” “Well, I've had my share of it. And she ain’t. Still—I * * * Just what would it be worth to you to have me out of the way?” “Oh, Tom—Tom—" I cried. But Obermuller got in front of me. “It would be worth exactiy one dollar and seventy-five cents. I think it will amount to about that for cab-hire. I guess the cars aren’t any too safe for you, or it might be less. It may amount to something more before I get you shipped before the mast on the first foreign-bound boat. But what's more important,” he added, bringing his fist down with a mightysthump on the table, “you have just ten seconds to make up your mind. At the end of that time I'll ring for the police.” N R e < T I went down to the boat to see it salil, Mag, at 7 this morning. No, not to say good-by to him. He didn't know I was there. 1t was to say good-by to my old Tommy; the one I loved. Truly I did love him, Mag, though he never cared for me. No, he didn’t. Men don’t pull down the women they love; I know that now. If Tom Dorgan had ever cared for me he wouldn’t have made a thief of me. If he’d cared, the last place on earth he’d have come to, when he knew the detectives would be on his track, would have been just the first place he made for. If he'd cared, he— But it's done, Mag. It's all over. Cheap—that’s what he 1s, this Tom Dorgan. Cheaply bad—a cheap bully, cheap-brained. Remember my wishing he'd have been a ventriloquist? Why, that man that tried to seil me to Ober- muller hasn’t sense enough to be a good scene-shifter. Oh— The firm of Dorgan & Olden is dis- solved, Mag. The retiring partner has gone into the theatrical business. As for Dorgan—the real one, poor fellow! jolly, handsome, blg Tom Dorgan—he died. Yes, he died, Maggie, and was buried - up there\in the prison grave- yard. A hard lot for a boy; but it's not the worst thing that can happen to him. He might become a man; such a man as that fellow that sailed away before the mast this morning. It to do, X. There I was seated in a box all alone —Miss Nancy Olden, by courtesy of the management, come to listen to the leading lady sing coon songs, that I might add her to my collection of take- offs. She's a fat leading lady, very fair and nearly fifty, I guess. But she’s got a rollicking, husky voice in her fat throat that’'s sung the dollars down deep into her pockets. They say she's planted them deeper still—in the foun- dations of apartment houses—and that now she’'s the richest roly-poly on the Rialto. Do you know, Maggie darlin’, what I was saying to myself there in the box, while I watched the stage and waited for Obermuller? He said he'd drop in later, perhaps. “Nance,” I sald, “I kind of fancy that apartment sort of idea myself. They tell you, Nancy, that when you've got the artistic temperament, that that’s all you'll ever have. But there's a chance—one in a hundred— for a body to get that temperament mixed with a business instinct. It doesn’t often happen. But when it does the result is—dollars. It may be, Nance—I shrewdly suspect it is a fact that you've got that marvelous mix- ture. Your early successes, Miss Olden, in another profession that I needn't name, would encourage the idea that you're not all heart and no head. I think, Nance, I shall have you mimic the artists during working hours and the business men when you're at play. 1 fancy apartment houses. They ap- peal to me. We'll call one ‘The Nancy’ and another ‘Olden Hall' and an- [ g “What'll I call the third apartment house, Mr. 0.?” 1 asked aloud, as I heard the rings on the portiere behind me click. He didn’t answer. Without turning my head I repeated the question. And yet—suddenly—before he could have answered, I knew something was wrong. I turned. And in that moment a man took the seat beside me and another stood facing me, with his back against the portieres. “Miss Olden?” asked. “Yes,” ““Nance Olden, the mimic, who enter- tains at private houses?"” I nodded. “You—you were at Mrs. Paul Gates’ just a week ago, and you gave your specialties there?"” ‘“Yes—yes, what Is it you want?” He was a little man, but very muscu- lar. I could note the play of his mus- cles even in the slight motion he made as he turned his body so as to get be- tween me and the audience, while he leaned toward me, watching me intent- ly with his small, quick, blue eyes. “We don’'t want to mage any scene here,” he said very low. “We want to do it up as quietly as we can. There might be some mistake, you know, and then you'd be sorry. So should we. I hope you'll be reasonable and it’ll be ali the better for you because—" “What are you talk—what—" I looked from him to the other fellow hebind us. He leaned a bit farther forward then and pulling his coat partly open he showed me a detective’s badge. And the other man quickly did the same. I sat back in my chair. The fat star on the stage, with her big mouth and big baby-face, was doing a cakewalk up and down close to the footlights, yelling the chorus of her song. T'll never mimic that song, Mag, al- though I can see her and hear it as plain as though I'd listened and watched her all my life. But there's no fun in it for me. I hate the very bars the orchestra plays before she be- gins to sing. I can’'t bear even to think of the words. The whole of it is full of horrible things—it smells of the jail —it looks like stripes—it—. “You're not going to faint?” asked the man, moving closer to me. “Me? I never fainted in my life. Where is he now—Tom Dorgan?"” “Tom Dorgan!” the man beside me “Yes. I was sure I saw him sail, but, of course, I was mistaken. He has sent you after me, has he? I can hardly believe it of Tom—even—even yet.” “1 don’t know anything that connects you with Dorgan. If he was in with you on this, you'd better remember, before you say anything more, that it’ll all be used against you.” The curtain had gone down and gcne up again. I was watching the star. She has such a boyish way of nodding her head, instead of bowing, after she waddles out to the center; and every time she wipes her lips with her lace ~handkerchief, as though she'd just taken one of the cecktails she makes in the play with all the skill of a bartender. I found myself doing the same thing—wiping my lips with that very same gesture, as though I had a fat, bare forearm like a rolling pin—when all at once the thought came to me: “You needn't bother, Nancy. It's all up. You won’t have any use for it all.” “Just what is the charge?” I asked, turning to the man beside me. “Stealing a purse containing $300 from Mrs. Paul Gates’ house on the night of April 27.” “What!” It was Obermuller. He had pushed the curtains aside; the crashing of the orchestra had prevented our hearing the clatter of the rings. He had pushed by the man standing there, had come in and—he had heard. “Nance!” he cried, don’t believe a word of it.” He turned in his quick way to the men. ““What are your or- ders?” “To take her to her flat and search gt Obermuller came over to me then and took my hand for a minute. “It's a pity they don't know about the Gray rose diamond,” he whispered, helping me on with my jacket. “They’d see how silly this little $300 business is. % * * Brace up, Nance Olden!” Oh, Mag, g, to hear a man like thatttalk to Jou as though you were his kind, whe# you have the feel of the coarse prison stripes between your dry, shaking fingers, and the close pris- on smell is already poisoning your nos- trils! “I don’t see"—my voice shook—"how you can believe—in me.” “Don’'t you?” he laughed. “That!s easy. You've got brains, Nance, and JOE ROSENBERG’S. JOI. ROSENBERG'S. offerings, You had better run and be on time for these good made expressly for us, under our own supervision. Twenty years handling hosiery has taught us all the defects—that’s the reason. There’s no better hosiery made than these. sell them: LADIES’ HOSE— Made of Egyptian open-worked, ribbed, embroidered in colored fast black and velvet finish .. 5 cotton, instep silk, 12:c LADIES’ HOSE— Made of fast black silk, fin- ished thread, double thread heels and toes, fect 1 fitting l:ind. A .D.e.r. cc 1226 LADIES’ HOSE— Made of Egyptian lisle, stain- less black, in open work new lace effect, Price . LADIES’ HOSE— In tan or russet colors, fancy ribbed, extra elastic tops, made of fine 40-gauge thread. You will appreciate rc}f;worth at LADIES’ HOSE— 1 We of genuine Maco thread, stainless black, white feet. just the stocking for sore and tender feet. A pmir..zsc For thin women, fast black, LADIES’' HOSE— made of sea island thread, jer- sey ribbed, the snug fitting kind, only to be had zsc here CHILDREN'S HOSE— Made of Egyptian thread, fast black, double heels, toes and knees, perfect in every detail, in 'hlsht, IIm'edium and heavy weight, all sizes; a pair. zsc Here's the way we will LADIES’ HOSE— Out sizes for large women, made of fast black English thread, more than even zsc exchange for LADIES’ HOSE— Made of Paris lisle, fast black open work lace effect, in new fancy patterns. of soc, Monday CHILDREN'S HOSE— Jersey ribbed, stainless black, double heels, toes and knees, medium weight, sizes; a pair . LADIES’ HOSE— For slender women, the per- fect fitting kind, Jersey ribbed, made of sea island thread, stainless black, velvet finished, double heels and toes:zsc LADIES’ HOSE— Madé of velvet finish thread, high spliced heels and toes, elastic ribbed tops, ex- fragtinaiily utod ooy ADE LADIES’ HOSE— Paris gauze lisle, sanitary fast black, (}ouble heels aréd toes, the perfect fitting kin: zsc Very low in price == 816 Market Street 11 O’Farrell Street “The Home of Good Hosiery.” the most imbecile thing you could do just now, when your foot is already on the ladder, would be just this—to get off in order to pick up a trinket out of the mud, when there's a fortune at the top waiting for you. Clever people don’t do asinine things. And other clever people know .hat they don't. You're clever, but so am I—in my weak, small way. Come rlong, little girl.” He pulled my hand in his arm and we walked out, followed by the two men. s Oh, no! It was all very quiet and looked just like a little theater party that had an early supper engagement. Obermuller nodded to the manager out in the deserted lobby, who stopped us and asked me what I thought of the star, You'll think me mad, Mag. Those fellows with the badges were sure I was, but Obermuller’s eyes only twin- kled, and the manager’s grin grew broad when, catching up the end of my skirt and cake-walking up and down, I sang under my breath that coon song that was trailing over and over through my head. “Bravo! bravo!” whispered the man- ager, hoarsely, clapping his hands softly. I gave one of those quick, funny, boyish nods the star inside affects and wiped my lps with my handkerchief. That brought down my house. Even the biggest fellow with the badge gig- gled recognizingly, and then put his hand quickly in front of his mouth and tried to look severe and official. The color had come back to Ober- muller’s face; it was worth dancing for —that. “Be patient, Mag; let me tell it my way.” There *wasn't room in the coupe waiting out in front for more than two. So Obermuller couldn’t come in it. But he put me in—Mag, dear, dear Mag— he put me in as if I was a lady—not like Gray; a real one. A thing like that counts when two detectives are watch- ing. It counted afterward in the way they treated me. The big man climbed up on the seat with the driver. The blue-eyed fellow got in and sat beside me, closing the door. “I'll be out there almost as soon as you are,” Obermuller said, standing a moment beside the lowered window. “You good fellow!” I said, and then, trying to laugh: “I'll do as much for you some day.” He shook his fist laughingly at me, and I waved my hand as we drove off. “You know, Miss, there may be some mistake about this,” said the man next to me, “and—" “Yes, there may be. is.” “I'm sure I'll be very glad if it is a mistake. They do happen—though not often. You spoke of Dorgan—" “Did 1?” “Yes, Tom Dorgan, who busted out of Sing Sing the other day.” “Surely you're mistaken,” I said, emiling right into his blue eyes. “The Tom Dorgan I mentioned is a sleight- of-hand performer at the Vaudeville. Ever see him?” “N—no."” “Clever fellow. You ought to. Per- haps you don’t recognize him under that name. On the bills he's Profess Haughwout. Stage people have many names, you know.” “Yes, so have—some other people.” I laughed, and he grinned back at me. “Now that's mean of you,” “I never had but one. needed.” it flashed through me then what a thing like this might do to a name. You know, Mag, every bit of recog- nition an actress steals from the world is so much capital. It isn’'t like the old graft when you had to begin new every time you took up a piece of work. And your name—the name the world knows —and its knowing it makes it worth having like everything—that name is the sum of every scheme you've planned, of every time you've got got away with the goods, of every laugh you've lifted, of every bit of cleverness you've thought out and em- bodied, of everything that's in you, of everything you are. But I didn’t dare think long of this. I turned to him. “Tell me about this charge,” I said. “Where was the purse? Whose was it? And why haven't they missed it till after a week?” “They missed it all right that night, But Mrs. Gates wanted it kept quiet till the servants had been shadowed and it was positively proved that they hadn't got away with it.” “And then she thought of me?” “And then she thought of you.” “I wonder why?" “Because you were the only person in that room except Mr. Gates, the lady who lost the purse, Mrs. Ramsay, and —eh?” In fact, there I said; It was all I Ramsay, you yes” “Not Mrs. Edward Ramsay delphia?” - “Oh, you know the “Oh, yes, I know printed, ame?” 1 know. inside flap an “It was lettering on the “T .don't know.” “Well, it was, and it contained three hundred dolla Mrs. Ramsay She had siipped under the fold of at the top of the bed k off your says read e put »n again when no was 11 me that hat ev rrant y nd you mean to t is all?” I-raged at hin you have to wa innocent gi “You didn’t beha , if you'll remembe “when I first came In fact, if that fellow in then I believe the whole job. added. I didn’t ans e a fort wh But I was tirec care, A year thing—the ris feel the I was volcano an more twis to the was to have bef the degene isn’t that that she used only one thin and you suppose it is, Ma don’t you dare to tell x When we got to th was already th ed out my k flourish. “Won't you e spend the eve They followe parlor. The t their coats and search and through miss, not a fail to there guying th in their shir iness has tak late. All their tri ings, their cheat bragging and bullyi his nerves bear get swears spiracy to freez like him out: h a paper prove it. But seemed to excit like a bad schoolboy. And I? Well, n far behind at was anything doi after them, and th the asked the big fe kitchen with Mr blue-eyed d reom, and 1'd t up a lun Mag, you i1d have Obermuller with a big salad while I wa The Cruelty how to cook, even if it other things. You wc lieved that the Trust had the throat and was choking t L breath out of him. You wouldn't have believed that our salaries hadn't been paid for three weeks, that « houses were dwindling ev night, that— I was thinking about it all there the back of my , t way out of it—you kno such an agreement as swears there is it's ag while we rattled on, the two of us a couple of children on a picnie, I heard a crash behind me. The salad bowl had slipped from Tmu 's fingers. He stood with his back turned to me, his eyes fixed uron that searching detec But he wasn't searching Mag. He was standi pointer that's scented ga meved the lounge out fro and there on the floor, spread T where it had fallen, lay a hand ne elephant-skin purse, with gold corners. From where I stood, Mag, I could read the plain gold lettering on the dark leather. I didn’'t have to move. It was plzin enough—quite plain. MRS. EDWARD RAMSAY. Hush, hush, Mag; if you take on so how can I tell you the rest? Obermuller got in front of me as I started to walk into the dining-room. I don't know what his idea was. I don't suppose he does exactly—if it wasn't to spare me the sight of that damned thing. Oh, how I hated it, that purse! I hated it as if it had been something alive that could be glad of what it had done. I wished it was alive that I could tear and rend it and stamp on it and throw it in a fire and drag it out again, with burned and bleeding nails, to tear it again and again. I wanted to fall on it and hide it; to push it far, far away out of sight; to stamp it down—down into the very bottom of the earth, where it could feel the hell | it was making for me. . But I only stood there, stupidly looking at it, having pushed past Obermuller, as though I never wante ed to see anything else. And then I heard that blue-eyed fellow's words. “Well,” he said, pulling on his coat as though he'd done a good day's work, “I guess you'd just better coma along with me.” as » be able to drubbing. in in ex was never ¥y when thers they'd ms—your and when sho apron Obermu nst the law— like when any = still He the more, as a had wa (Continued Next Sunday.)