The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, October 25, 1901, Page 3

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

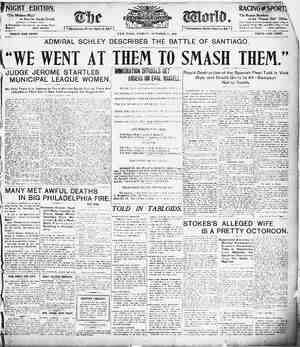

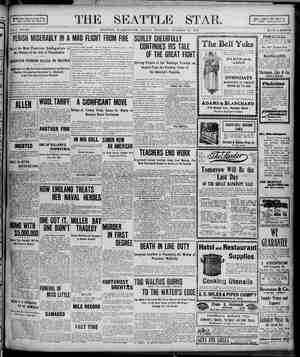

THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 25, 1901 CONCERNING TH SAYS HE ACTED ON SCHLEY'S SIGNALS Fiagship Brooklyn Fights a Bunch of the Spaniards at One Time and Aids in| the Destruction of the Fleet of Cervera £S Continued From Page One. enywhere. I then went aboard my own flag- ship in order to hasten the operations of coal- ing. While there the Algonquin came out, bearing an order from the Secretary of the Navy to go off Havana. I signaled the admiral to w whether or not he understood that my ers were to g0 off Havana. He replied by signal that he understood that his coming to Key West modified my orders and that 1 should be prepared to carry out the orders we had sgreed upon in the afternoon. I do not re- member whether that on _the afternoon or in the morning, but it was before 1 left for Cienfuegos.” Departure of the Squadron. The mext move of the fiying squadron, Ad- miral Schiey said, was from Key West to Cien- fuegos, and the admiral told how, as the com- mander in chief of that squadron, he had the vessels coaled so that at 7 or § o'clock on the morning of May 15 all the ships of the fleet turned their backs upon American ol and laid their course for the southern coast of Cuba. This, he said, was done under the order of the commander in chief, Admiral Sampson. At this point the witness quoted Admiral Sampson’s order not_failing to point out as he went hat in this order the admiral had said: 1 have the situation more in hand 1 write you and give you any information that suggests itself. The first eve: the voyage toward Cienfuegos occ ter West three or t was then that he met in charge of the sub-squad- lehead at its head, which uty on Cuban coast near Captain McCalla. ron with the Ma bad been doing Cienfuegos, whither the commodore Wwith his fiying squadron was bound. He related how, in sccordance with usual custom when & naval officer meets & superior in rank at sea, Ceptain McCalla b He told how McCalla had sent the Eagle municate with the flying squadeon. Ad- v also mentioned that the Scorpion > intercept the Eagle for the g whatever information she le,” said he, “the Scorpion re- rted through the megaphone, y as is reported in his log, which was =2l the information he gave us. The Eagle afterward passed close enough to e Brooklyn to hail her by the megaphone and d that there was news. I was on r deck. The thing seemed to be al- ed into my mind, but after what I d, 1 begin to think that maybe was mistaken.™ Meets ‘Captain Chester. 1 also_related his meeting the 4 the Vesuvius the mext morning onio. Captain Chester, in com- cinnati, came aboard the ng for about three-guarters of an hour ated the detalls of his con- Versetion with Captain Chester. saying that they had “ihreshed out & £ood many subjects. After mentioning & number of the subjects Swhich 4id not bear upon the present inquiry the admiral said that Captain Chester bad ex- pressed himself as specially desirous of join- ing the fiving squadron with his ship but said hat nis coal supply was so limited ould be compelled to go to Key West at a ery early date to replenish it. Admiral v said that he had terminated this part pversetion by saying to Captain Ches- as his ship wae not in his (Schley’s) he could mot attach him to In the same connection witness said ester had asked permission to from the flying squadron ey) had declined this prop- hie report of this conversation, al sald: asked him if he had ever cruised in Indies, #s I had never been on the “uba, and if he knew of any d be favorable for coaling, sirly smooth water could be expected e suggested a place some thirty miles to ne eastward on & bank, or to the southward cn another bank, coaling upon which would 1" and dependent upon the esther and the sea. the admiral added, *‘recollect other conversation, except Captain Chester's disappointment that ke could not squadron, which I thought e eworthy. P In response to a request from Raynor., the ral said that ope of the places that had n recommended by Captain Chester for ling was to the southward of Clenfuegos in the open sea. “I did not agree,” he sald, “‘that that would be & good place to coal, because conditions in an ordinary sea would be aggravated in shoal water." Admiral Bchley placed his arrival off Clen- fiegos at near midnight of May 21. He told of hearing guns early that evening while stiil thirty or forty miles distant from the Cuban t. Describing this incident, he said: ““Toward sundown of -that afternoon I was e:anding on the bridge of the Brookiyn and 4 inctly heard six or seven guns fired with the cadence of a salute. The fact of hearing thoee s was undoubted, so much so that the o ot the deck spoke of it. 1 happened to be there gt the time.” He said that the fleet stopped for the night or tw e miles off shore off Clenfuegos; that he had sent the Scorpion ahead of the set as & pliot, and toward daylight on the wing mornine. May 22, all the ships had steamed im close to the harbor entrance. recollection is,” he said, “‘that we wen* & mile and looked at the harbor. But € to trees and other obstructions it was ossible to see into the harbor. I never saw mokestacks, and I was & very close deck, generally from § o'clock in the = g u 12 or 1 o'clock at night. There was scarcely & circumstance of any kind that escaped me.” o - 1m - w m 1 #aid that after this inspection harbor he had taken a p sition with e or four miles out. he said, “gave the position uedron was from the beach by the e of the surf, which ordinarily is not #cen beyond six miles except at & great eleva- Dispatch From Sampson. At 8 o'clock on the evening of the 224 the | torpedo-boat Dupont, the admiral rived with a dispatch from Admiral Sampson. Tre dispatch referred to was the - Dear Schley” letter. The witness said: 1 & it ember the fact until within the past few mon because there were du- plicates of th r, but I mow recall ft the fact in o the injunction con- tained in that communicate with the out whose presence off Santiago I n, es 1 think the admiral was, on t of orders having been sent directing to proceed the direction of the Span- re ist mein to Jook for the squadron. e ad- | miral was Dot certain whether they had got back, nor was L Ther .4mirel Schley also said that the Towa had ived to join the fleet on the 224, but he did remember that it had brought any dis- ope_containing some from his (Schley’s) not paiches beyond an en et zers, one of which “That fact,” he sald, “fixed that in my mind. A good many of the things about which I am tetsifying burned themselves into my ory because I was the most interested ¥ I cannot recall anything in connection with the Jowa at all.” Coming to the blockade off Clenfuegos the adrairal explained the formation of his fleet there, saying that the steaming which had been mentioned in the logs was for the pur- | pose of overcoming the effect of a current wh ch set directly into the shore. He said the ships were constantly settling into the beach and were obliged almost every hour to steam for a mile or two. “'And that,” he said, “‘ac counts for a good deal of what is stated in the logs about steaming.” Ir this seme connection the admiral said the: he had fixed the position of the squadron every morning and every afternoon by what . i® nown as the four point bearing. n variable At “‘we had an in- in a general e were closer ht.”” he continued, light breeze, and we kept on a general bearing. ht, and that,” he said emphatically, the rule of the squadron always. We closer_at might at both Clenfuegos and ago. The idea of keeping the squadron ation Auring the night or in line of le ready for any emergency Was never gbandoned. The arrangement during the day was s little feigned disorder, in the hope tha. we might invite those people out. We there would be difficulty in getting because my flagship was of greater draught most of the others. the channels were very tortuous, and our only hope, at least our only wish, was that they must come out. The mowements of the squadron were rather an itatioh, usually. That was what I felt dur- g all the period of this blockade.” At thie point Admiral Schley digressed for a morient to refer to the conversation he had with Admiral Sampson before leaving Key TWest “which he said had induced the belfef that the Spanish squadron’s objective was Cien. fuesos Was Not Disrespectful. Tie afmirai then related the particulars of through Commodore Remey, directing me | hiey said, af- | acked permission to pass | limited that he | the | sald, ar- | the Scorpion to the | to him on board the Brooklyn, pont arrived oif Cienfuegos. Lieutenant Wood was in a pitiable condition of cxhaustion because of his arduous duties on a torpedo boat. I told him,” sald the admiral, “that if 1 were a King I would promotie every torpedo officer five grades if 1 could.” Continuing, the admiral related how Lieuten- ant Wood had handed him the dispatch and added “I think he did@ me injustice when he spoke of my speaking disrespectfully of Admiral Sampson. 1 used no such term. There was no reason why I should have done so. I invaria- bly spoke of him as Admiral Sampson, and I do not_ recollect one word of the conversation which Lieutenant Wood recited—not one word, and I recollect a good many things pretty well, I am glad to say, and very little from imagin: ation.” The admiral said that the Hawk arrived about 8 o’'clock on the morning of May 23. This vessel, he saild, had brought the dispatch from Sampson which is designated as No. 8 This is the dispatch in which the commander in chief notified the commander of the flying squadron that the Spanish fleet probably was at Santiago, and directed him, “If satisfled that they are not at Cienfuegos, to proceed with all dispatch to Santiago.” The witness said_he had received duplicate copies of dispatch No. 8 and said he identified the copy brought by the Hawk as the first re ceived by marginal notes which had been made on the copy. He also sald that a copy of No. 7, the “Dear Schley” letter, and also |a copy of the McCalla memorandum had been received by the Hawk, saving that these facts | were fixed In his mind by the circumstances | that on that date a signal had been given to the squadron mnotifying the vessels that there was & rumor that Cervera's fleet was at San- | tlago. *‘That,” he said, “is fixed in my mind. | because if I had got it the day before I would bhave made that signal to the squadron as my | habit was to keep them all informed.’” | No Verbal Orders From Hood. Relating the fact of the arrival of the Cas- tine and a collier on the 23d, Admiral Schl | referred to his reported conversation with Licu- | tenant Hood, which, he said, “’is one of the other conversations I do not remember. I think,” he went on, “‘that I can show you by a memorandum of Mr. Hood's that if he had any verbal orders he forgot to report them. The admiral then referred to a memoran- dum from the Dolphin published in the appen- dix to the report of the chief of the Bureau of Navigation, reading as follows: “The Hawk has just reported from Cienfue- gos With dispatches from Schiey. Hcod says & good number of officers don't believe the Spaniards are there at all, although they can only surmise.”” b “That,” remarked the admiral, *‘would go to indicate that Mr. Hood was not very cer- tain in his own mind, or, if he had brought any verbal instructions to me, that he failed to report the fact to the commander in chief. | Below it is also a border information which I should have been very glad to have had. Mr. Hood got Into the anchorage, I think, somec time about 8 o'clock. ‘The Adula did not get into the anchorage at Cienfuegos before 10 or 11 o'clotk. Lieutenant Hood did not board that ship in my presence. She had already been boarded. 1If he boarded her and got this news and failed to deliver it to me then he com- mitted an indiscretion, for 1 was the senior officer and he did not know what I was going to do with her. I should have been glad to | bave had his information. So that with this | note and this information I think Mr. Hood | remembered a good deal of what he said to hme, b:t he forgot a good deal that he should ave done.” Blockade at Cienfuegos. Admiral Schley gave further details concern- ing the blockade at Cientuegos, telling how he bad observed men laying mines across the | river and how he had established a picket line inside the main line of biockade. Ho again reterred to the arrival of the Dupont, | which, he sald, was very short of coal, having, | as was reported, only five or =ix tons aboard. He also told of the difficulties experienced in puttng a lew additional tons aboard the tor- Pedo-boat, and in this connection said: The work struck me as being one of such difficulty that any attempt to coal a larger vessel by boats would not only be exhausting and fatiguing, but almost impossible beyond a day or two.” “ihe incident of the arrival of the British | ship Adula was related in much detail, the ad- miral telling how he had had her boarded and how she had brought information in the shape of a war bulletin which had_stated that tne Spanish fleet had arrived at Santiago on May 19 and had left there on the following day. Remarking upon the report contained in this bulletin the admiral said: . ““That, of course, taken with the manner of my approach and the distance thirty-six to forty-eight hours a to_the belief that I entertained. The admiral then related how the commander of the Adula had been allowed upon specious promises to-go into the harbor and had not come out on the following day as he had Ppromised to do. Admiral Schley sald that on the night of the | 23d he had seen three horizontal lights to the eastward and to the westward of the harbor of_Clenfuegos. “The one to the eastward,” he said, ‘‘was in the mountains and I should say ten miles from the coast, and certainly 500 feet up; the others to the westward, about five or six miles in on the beach, but back of it on the high land.” He sald that while the squadron lay off Clen- fuegos the winds were fresh and there was quite a rolling swell to the eea. In this co nection Admiral Schley referred to the fact that he had not been informed that there was any system of signals for communicating with the insurgents, and he said that he did not know that there were any insurgents to the westward of Clenfuegos. This fact, he said, together with the circumstance that ‘the Adula had not come, that Lieutenant Southerland had failed to communicate any information, and the further fact that McCalla’s squadron had been withdrawn from the vicinity were responsible for the delay in communicating with the insurgents. Did Not Waste Ammunition. “Of course,”” he sald, “‘to risk a boat through | the surf on a coast belleved to be occupled by | the enemy must have resulted in a repetition of Captain McCalla’s experiment. He found that the coast was pretty well occupied. I | saw cavairy once or twice, both to the east and | to the west of this point. They appeared for | 2 moment. and immediately got out of sight. ‘r( thought that to waste ammunition upon a | ¥, lent color solitary cavalryman was like shooting big guns at sparrows, and that killing one or two men would not affect the result. I thought it would be better to reserve all the ammuni- tion we had for use against the squadron which 1 believed to be somewhere in that sea, and it seems to me that was a conclusion. I did everything that was possible during the time we were there to maintain the blockade 1 that was contemplated. 1 did all the coaling that was practicable or possible.”” Continuing on the subject of coaling Admiral | Schley sald: “After we got hold of colliers which were | very much better fitted to resist shock as well as to deliver coal rapidly, perhaps, and with | the later experience of the war I might have coaled on days with worse weather. We had & good many accidents about which no mel tion has been made. One of the colliers had to g0 to New York absolutely smashed in. The Merrimac herself had several holes punched through her, and my impression now is that a portion of the top works of the Sterling was injured in some way, but we managed | with more patience to do a little better than at first. There always was at Clenfuegos a | Tolling swell and vessels with projecting spon- | sons or projecting guns were always in dan- | ger. I recollect once that one of the six- pounder guns of the Brooklyn was bent at an | angle of 3) degrees by coming into collision | with one of these colliers. Of course the twin screws made it extremely dangerous to coal except under the most favorable conditions. | The problem frelenled to me at Clenfuegos to | solve—that of coaling—has disturbed the na- vies of the world for fifty years. I know we accomplished this reasonably well under the circumstances. Hears of Insurgents’ Code. i | ©On the morning of May 2% Captain McCalla | had arrived off Cienfuegos with the Marblehead | and the Vixen, and the captain had, according | to Admiral Schiey immediately réported to him on board the Brooklyn. The witness sald he then heard for the first time of the code of signals arranged for communicating with the insurgents at Clenfuegos, I was a great deal surprised,” said the wit- ness, “and asked who made these arrange- ments. He said: ‘I did when I was here be- | fore.” 1 asked why it was not communicated to me. That he did not know, of course. He was not answerable for that. T sald: ‘Where are | those fellows?” He sald: ‘I communicated with them when I was here last to the wes ward some twelve or fourteen miles, but they are migratory and they may or may not be there 1 said: 'Go ahead and take up the line of search and let me know.’ "’ The admiral then told of his sending Captain McCalla ashore and of the latter's reporting, about 4 o'clock on the 24th. he thought that the enemy was mot at Cienfuegos, which fact he had learned by communication with the Cubans on shore. An hour or two had then, the wit- Bess said. been consumed in the preparation of dispatches, including a dispatch to be sent to the visit of Lieutenant Wood of the Dupont | when the Du- | He said that | being about | = (g1 together. oo the Secretary of the Navy, ana about 6 o'clock the squadron steamed to the south. ““I think,” he sald, ‘‘that we finally got under | way between 7 and § o'clock on a course of | about southeast. .The orders to the squadron were by signal. 1 dld not care whether the enemy saw them or not. 1 am quite sure that the distance which we had steamed from the preliminary formation until the final depart- ure was outside of any distance they could have been read or seen from shore.” Speaking of the weather condition night of the 24th, after the squadron under way, the admiral sald that he bered that the night was a dirty one and the sky lowering. It was rainy in squalls, he said. He recalled especlally that he had looked out through a porthole twenty feet above water ray dashed In. he sald, “‘weather of that sort did not mean much to the larger ships, but to the smaller ones it did.” Giving the formation of the squadron he said that he had kept the colller on his weather side, 50 thak in case the enemy should appear that vessel could be protected or sunk. The arrangement also had contemplated that the Marblehead would be able, with the two smaller vessels, to act as torpedo-boat destroy- ers. He said his policy had been to keep the squadron together as a unit, and added: Formation as a Unit. ““I think it will be admitted in changing the location of a squadron from one port to an- other that it would be unmilitary and unwise to proceed in any other formation than as a unit. My impression is that useful auxiliaries and necessary supplies never should be aban- doned except under the very strictest military necessit Adrh 25th as rough for the smaller ships. “I remember,” he said, ‘‘that the Marble- head carried away one of her booms that was alongside on account of the sea. The Vixen took green seas over her bows and badly in- jured a man. The Eagle filled one of her. for- ward compartments. Both of these ships con- stantly dropped astern. The squadron, of course, slowed for them. On several occasions the Merrimac signaled the disarrangemefit of her steering gear and of her engines, necessi- tating stops. Coaling on’ the 25th would have been absolutely impossible. I watched the sea perhaps more carefully than any one else and was ready to avail of the earllest oportunit to take advantage of it, and I felt that was very much more capable and very much more competent thap any one else in the squadron of judsins when coaling-was pos- sible.” Coming to the 26th Admiral Schley said that the weather was still rough, and he related the incident of sending Commander Souther- land away with the Eagle. “He did not,” the admiral said, “‘insist upon coaling his ship, because it would have been absurd; it was impossible. His ship at the time was laboring a great deal, slashing and rolling about. He regretted having to leave the squadron for coal as well as myself. His contention, however, ‘that he could coal on that occasion was utterly untenable. He could have coaled, I suppose, in boats, but he would have burned the coal as fast as he got it on board. ““We continued in an easterly course,” said the admiral, again taking up the thread of his narrative, “as my orders contemplated ap- proaching cautiously and as they also con- veyed to me the information that probably when I left Clenfuegos the enemy would leave Santiago I lald such a course as I thought would give me a wide horizon. and if he did leave T could not imagine he would try to pass inside of me. I estimated, of course, he would pass to the southward. My course as projected would have, of course, gone to China if_there had been no islands in'the way."” The admiral then told how, upon reaching a point southward from Santiago, about 4 or 5 o'clock in the afternoon of May 26, he had encountcred the scout boats St. Paul, Minne- apolis and Yale, but before relating the details of coming up with them he digressed sufficient- 1y to refer to a dispatch in which he had men- tioned his intention of delaying until the 25th his. departure from Cienfuegos which, he ex- | plained, was for the purpose of taking up the Scorpion, which vessel had been expected. back th or 25th. he sald, “‘was the suggestion, but we can make a great many suggestions and say a gocd many things and then we are priv- ileged not to follow. them.” Admiral Defends His Course. At this point the admiral entered upon an- other defense of his course by saying: ‘I was on the south side of Cuba, of course invested, 1 thought, with entire responsibility. 1 was 7ot In communication by telegraph. I aia not know that we had secret agents In Havana. I did not know that there was any means of communicating with the insurgents. If that were known, I should have known it also because I was acting in an entirely in- dependent capacity, I may almost say. I could not be reached by telegrams and a good deal 1 did had to be left to guessing. Aud some times 1 guessed right and sometimes 1 guessed wrong, and 1 suppose in the light of recent events we are all liable to do that.”” The witness then referred to his picking up the scout boats. In this connection he agaln spoke of the weather conditions on the voy- age from Clenfuegos over, saying that Captain Cook reported that he had never seen more motion on the Brooklyn, and that some of the youngsters in the steerage were seasick, which is an unusual thing. He then related the incident of Captain Sigs- bee's coming aboard the Brooklyn from the St. Paul, saying that the visit had impressed itself vividly upon his mind. ‘I recollect distinctly,” he said, “‘that he had on rubber boots and an old blockading cap, which we all wore more or less, and an ordi- nary blouse suit.’” The admiral then proceeded to give the In- formation which Captain Sigsbee had brought, prefacing what he had to say with the state- ment that he did not believe Captain Sigsbee would misstate anything for his commission. “I don’t believe.” the admiral sald, ‘that he is capable of stating what is not true. -In this instance I think his recollection is at fault and not his veracity. I said to him: on the had got remem- ‘Captain, have you got the Dons here? He sald to me: °No, they are not in here. I have been in very close.’ I don’t know but what he sald ‘sketching,’ but he certainly said: “They are not here; they are only reported here’ 1 sald to him: ‘Have any of the other vessels seen them, the Yale or the Massachu- 7 "He sald: °‘No, they have not. They assured me 5o’ That was the assurance hich I referred when I spoke of the assur- to wl ance of such men as Wise and Jewell and Sigsbee. 1 do not belleve that any of thosa men would misstate the conditions at all, but 1 assured them from the communication from Sigsbee that he was bearing to me the as- surances of all of them.” Relating his interview with Pllot Eduardo Nunez, Admiral Schley said that Nunez had expreesad the opinion that it would have been almost impossible for ships of the size of those of the Spanish fleet to enter the Santf- ago harbor, the pilot saying that the entrance was not only shallow but tortuous. Assumes the Responsibility. Referring in a general way to Captain Sigs- bee's visit, Admiral Schley said: “My habit of life, not only in point of com- mand of a squadron, but also in command of a ship, was to assume the responsibility and the danger of censure of any movement that might Justify it, but 1 was never willing under any circumstances to be a participant in glories 1 would not divide. That was the general prin- ciple upon which I acted in this matter. I did not call any council of war. The information which these people gave me led me to infer that the telegraphic information was a ruse precisely similar to that which was tele- graphed from Cadiz that the squadron had re- turr2d from the Cape Verde Islands. That would have been my policy if 1 had been in control, and it any of us at any time made any mistakes during the campaign of Santiago or elsewhere, it was in supposing that the Spaniards would ever do right at the right time, That prebably was the only reason we made any mistakes that we did make. I determined that, that being the case, a move eastward would be unwise, in that I knew Admiral Sampson ‘would have moved 0 the eastward of Havana, It would not have been wise for me to have uncovered Santlago. The military importance of that movement would have been to guard the westward, as that would have been the only place they could have got in behind. As those in the {nterlor had an absolute control of the entire line, our movements every minute of the day were known in Havana, and I have often been surprised that Cervera did not leave Santiago when I left Clenfuegos. I found out afterward why he did not do it—simply be- cause he could not—and therefore we did not suffer any.’ Relating the particulars of the breaking down of the collier Merrimac on the evening of the 25th, Admiral Schley said that his first deter- mination had been to have her towed to Key West by the Yale, as he did not consider it desirable to have an unmanageable colller with b It then occurred to me,” he said. ‘‘that if we did send her to Key West with the Yale al Schley spoke of the weather on the | and she was overtaken we would be out a collier and the Spanish force, if they were out- side, would be in so much coal.” Explains Retrograde Movement. In this connection Admiral Schley explained his retrograde Iovement, so-calied, to the westward, saying that hé had not considered | the economical aspect of this step, &s economi- cal features could never be taken into consid- eration in military movements. He had, he said, made careful inquiry as to the coal sup- ply of the various ships and had turned over in_his mind their endurance, in battle. I was,” he said, “‘thinking over in my mind that a squadron, in Its ccziing endurance, or at least 1n its speeding enaurance, was equal only to its weakest members, just as the speed of a fleet depends upon its siowest vessel; that it would be necessary to equalize as nearly as we could their standards of steam in order to be of effective use as a unit, and that de- termined the westward movement. “Now the telegram I sent to the Hon. Sec- retary of the Navy did not refer only fo the battleship, as interpreted, but it referred to the entire fleet. We had at that time ten ships in the squadron, seven of which were short of coal. ‘Lhere were the auxiliaries and _the Texas. ~'fhe auxillaries and the Marblehead and the Vixen, I think, were moderately well flled. The amount of coal which we transmit- ted should have, I think, called attention to that fact. Now, as has been testified to and shown, 1 think almost every one who has had any command during a war wherein: large res- ponsibilities were involved would have been unwise not to have considered his own ac- complishments. We could not assume that the enemy was going to chase toward our base; it was probable he would chase toward his own. He would have been there pretty regularly or among his more intimate friends at Marti- nique. 1 do not think he would have been Lable to have gone to our base, and thererore any calculation which took into consideration the efriciency of the squadron had to assume that it would be in a direction least favorable to us and most favorable to the enemy.’’ ‘Admiral Schley again referred to the unman. ageable condition of the colller Merrimac, say- ing that no prudent commander would have | sent a ship alongside of her. Referring to the arrival of the Harvard, the witness spoke of the discrepancy in the re- port as to the information which captain, now Rear Admiral Cotton, of that vessel, had brought aboard the Brooklyn. He said that the dispatch which Captain Cotton had brought aboard had said that the department’s advices indicated that the Spanish fcet was at San- tiago, Dispatch Never Reached Him. Continuing, he sald: ‘‘Captain Cotton eald he delivered a dis- patch to me from Admiral Sampson stating that they were there. That dispatch never reached me. I never saw it. I never heard of it until the other day. If it ever was de- livered it should have been found among my papers, but it could not have been delivered to me for the reason that a dispatch of that character would have burned itself so indelibly on my mind I never could have forgotten it,, never. Captain Cotton did not communicate it to me, and there I think his recollection is at fault and not his veracity, because I do not belleve he would state anything that was not so.. “Neither my first lleutenant, neither my flag lleutenant nor my secretary ever saw it or can remember it, and it is a little strange that three persons who had access to my papers at all times should have falled to re- member a dispatch of that importance. So it is a mistake. I never saw it. I do not re- member it. I have no recollection of it, nor of a good many things which I have heard during this investigation.” Admiral Sehley at this point returned to his conversation at Cleafuegos with Captain Mec- Calla. He exonerated the captain from any intention to do him injustice, but he eaid that the captain had failed to give all of that con- versation. Discussing again his dispatch to the depart- ment concerning the department’s orders, the admiral sald: “If my reply to the telegram of the Secretary of the Navy is not on record, I would like to put it there in the terms I sent it, because I wrote it in Epglish, gave it to Captain Cotton, asked him to turn it into cipher and confirmed it afterward in a letter to the department, which was received. The dispatch is here, and has been in the department for nearly three years. I do not belleve for one moment that in the translation of it there was any intention to mutilate it, but I think, In the choice of words which were not exactly of the same meaning, the dispatch did not get to the de- partment entirely as I intended it should. Upon this dispatch is based the charge of a obedience of orders. I contend that there was no disobedience of orders. There would have been disobedience of orders if I had abandoned my station, but, having returned to the station without other direction and having found that the department’s information was correct, I hold that I did not disobey orders and I think that thie dispatch, read and interpreted as sent, will relieve that charge.” No Disobedience of Orders. Admiral’ Schley pointed out that the infor- mation eent from the Navy Department &s to the whereabouts of the Cuban insurgents in the vicinity of Santiago was erroneous, the dispatch placing them much nearer that city than they were. “If we hail gone to the place Indicated,” he said, “at the time we recelved the dispateh ‘:vledwould have been in all probability gob- Again referring to his own dispatch, Admiral Schiey said that it had been delivered in Eng- lish, but, he added, “read in the light of this order and in view of the fact that the squad- ron did not return to Key West, whatever may have been our intention or purposes, I say there was no disobedience of that order, and there 18 no order there to go back. It was simply that the department looked to me to establish a fact of which it was not certain.” In response to a request of Raynor for the exact wording of the sentence in the dispatch in_dispute, Admiral Schley gave It as follows: “It is to be regretted that the department's orders cannot be abbyed, eatnestly as we have all striven to that end.’ This, he said, was the authentic version of the sentence, and was as he sent it. The admiral was in the midst of the dis- cussion of the ‘‘disobedience of orders’ dis- patch when the old clock in the courtroom struck four and Admiral Dewey announced an adjournment for the day, notwithstanding that Admiral Schiey told him that he would like to conclude his testimony at this sitting. The admiral was calm and collected throughout the two hours that he in the witness chair, and he spoke In tones which, while not loud,” were so distinct that his words were easily heard. | SRS CLARK’S NARRATIVE. Captain of the Oregon Tells of That Battleship’s Work at Santiago. WASHINGTON, Oct. 24—Every available unreserved seat in the large room in the gun- ners’ workshop at the navy yard, where the Schley court of Inquiry is sitting, was occu- pled to-day half an hour before the court was called to order at 11 o'clock. The announce- ment of the approaching close of the case and of the possibility that Admiral Schley would take the witness stand during the, day had the effect of increasing the public inferest and of bringing to the courtroom a far larger number than could hear the proceedings. A number of yesterday's witnesses were re- called as usual for the correction of testimony, and after they had finished Lieutenant Com- mander Charles H. Harlow, who had concluded his statement in chief when the court adjourned yesterday, was immediately taken in hand by Captain Lemly for cross-examination. This was_devoted principally to the notes taken by Harlow of the battle of July 3 from the Vixen's deck, but was mot very extended. After Commander Harlow Rear Admiral Barker and Captain M. C. Borden of the ma- rines were introduced to testify to incidents of the Cuban campaign. Captain Charles B. Clark, whose record on the Oregon during the campaign of '98 I8 the boast of every Amerlcan citizen, was called as the third witness of the day, and the last witness in Admiral Schiey's behalf to be heard before the admiral him. self should come on. Major Murphy corrected his testimony of ye: terday so s to say that the vessels of the fiy- ing_squadron in steaming back and forth at night in front of the mouth of the harbar at Santiago had gone only about 800 yards to elther side of the harbor, Instead of 100 yards, as stated yesterday. % Schley’s Gallant Speech. In response to a question by Raynor M Murphy detailed an incident in which ey modore Schley figured at the close of the bat- tle of July 3. Major Murphy sald: “I remember the incident dlstinctly because it made a very great impression on me at the time. It was When they were preparing & cut- ter to take Captain Cook to the Colon fo re- SCHLEY'S ASSURANGE TO SAMPSON OF LOYAL, UNRESERVED FEALTY E looked over maps, and I must say that I agrecd wwith him. I could not imagine that any one who had studied the military situation of the island at all could have supposed that Santiago would have filled any of the conditions of his instructions. We had quite a talk 1 told him that I had been ordered to report for duty to Admiral Remey, which, I im- ‘agined, necessarily meant himself, and that I wanted to assure him at the outset that I should be loyal_absolutely and unreservedly to the cause that we were both representing. Captain Chadwick, who was present—I dow’t remember all the time or not—said, ‘Ofcourse, commodore, any one who has knowon your character would know that it would be “impossible for you to be otherwise than loyal’ ”—From Schley's statement relating to his meeting with Sampson at Key West. ] _— celve the surrender of that ship. She had hauled down her flag and was ashore. The offi- cers and many of the men were gathered for- ward in the neighborhood of the forecastle and Commodore Schley addressed the men, caution- ing them not to cheer when the-Spanish ca tain came ‘on board. He spoke of their gal- lantry, sayidg that they had made a good fight and that they should not be humiliated; that we should treat them chivalrously and not hu- millate them by cheering. It was a gallant speech, and ‘we all felt it very deeply. The commodore made the same speech about mid- night of the same day, when we were ranging alongside the Iowa, and we had learned that Admiral Cervera and his officers were on board that ship. It afterward developed that Ad- | miral Cervera heard Commodore Schley make the remark and he appreciated jt very much, so we were told."” Brooklyn Target of the Enemy. Describing the course of the Brooklyn during :?Aeeahattle of July 3, Commander Harlow tes- “I gaw the Brooklyn receiving almost the en- HE BATTLESHIP OREGON TESTIFIES E WORK OF THAT VESSEL IN GRE AT BATTLE GALLANT CONDUCT TOWARD VANQUISHED Major of Marines Tells How Schley Made a Speech Requesting the Tars Not to Cheer Within the Hearing of the Captured Men 2 £S5 did as he progressed, and he was soon distinctly | heard in the vicinity of the court. | cription of the Battle. ! At the request of Raynor, he began a descrip: | tion of the battle of July 3, as follows: | “*“When we discovered the Spanish ships com- tire fire of the two leading ships with an oc- casional shot from the Colon. 1 was in a po- sition to see a flash, and shortly afterward the fall of the projectile, and these showed that a large proportion was.about the Brooklyn. The Colon evidently was using smokeless powder, and I was not able to tell so well where her shots fell.” .| ing out,_our fleet closed in_ at once to atiaci : them, cach ship beins_ordered to keep he The witness sald he was satisfied that the | head’ directly toward the harbor _emtrance. fire of the Brooklyn set the Viscaya on fire and caused her to run ashore. There was no other American ship within range of the Vis- caya at that time. The Maria Teresa was driven ashore by the concentrated fire of all the ships of the American fleet. The Oquendu was so0 far in the rear he could not estimate what vessels caused her destruction. In re- sponse to a question by the court, Commander Harlow said that the Vixen was able to main- The Spaniards turned to the westward, break- ing through cur line and crossing it, and our ships swung off to the westward in pursuit. Both sides opened fire promptly and fired ra; idly. Dense smoke obscured the vessels, maXe ing it difficult to distinguish them. ““The Oregon ran between the Iowa and the Texas and the next ships to the westward in our line, and soon after we sighted four Span- ish ships ahead, apparently uninjured, at that { | that tain the standard speed of nine knots an hour | HMe;, Thev had gained so much grount thal With the fleet in the voyage from Clenfuegs | jempting to escape, but It was soon evident to Santiago. He also said In response to a | teriuoe ‘o SScepe. DIE b RS HoOn e question by the court that with searchlights the Vixen was near enough to the mouth of the harbor at Santiago to see the enemy's ships in case of an effort to escape. The large audience manifested signs of in- terest as the captain of the Oregon approached the witness stand. Admiral Dewey smiled as he walked around to the end of the table to administer the oath. Captain Clark at first spoke in an undertone and was two or three times requested to raise his voice. This he which afterward proved to be the Maria Ter. esa. the flagship, and I thought we should bring her to close action, but might be posed to the concentrated fire of all the ships. Just then the smoke lifted or broke away to the left, and I discovered the Brooklyn. | She was well forward of our port beam aad Continued on Page Nine. proval. OurNineDolla The continued demand for our $9 suits proves that they are meeting with marked ap- The suits actually sell themselves. patterns, selects something to his liking and the sale is made. This can only be done when clothes have a good outward appearance. We will vouch for the “inside” of these suits—for the making and material, on which the wear depends. We know that they are all wool and well made by union labor, that the color is fast, that the suits are worthy the price. Should a customer disagree with our opin- jons he can have his money back. Need we say more of our faith in the suits? - They are made in solid colors and fancy patterns from cheviots, tweeds, worsteds and serges. A new shipment of these goods has just arrived from our workshops. Buy direct from us, the makers, and save twenty-five per cent. . 9 . .® ° ) Threc days’ special in child’s clothes As our last three-day special sale was so successful, we will have another sale for Fri- day (to-day), Saturday and Monday. The suits are vestees and sailors, each made from dura- ble materials, neatly trimmed; they are stylish little suits and are really worth more than the special price, which for the three days—to-day, to-morrow and Monday—will be If after examining the suit closely in their home parents think that the suit is not worth the price, they can Special three days’ sale of child’s reefers, like picture, made of covert cloth and brown frieze with inlaid velvet collar, ages 3 to 8, good weight for winter, regular $3.00 value, for day, Saturday and Monday the special sale priceis Boys’ knee pants, made of remnhnts from our tailoring department, all-wool goods, well made, ages 4 to 16 years; regular cloth the prices would be $1.00 to $1.50: being made from remnants we charge you only for the making, which is Boys' derby hats on special sale at $1.30. Boys' golf caps, elegant assortment, at 2 for 25e¢. z Boys’ unlaundered shirt waists, made of per- cale and cheviot, with detachable patent belts, ages 4 to 13, 2 fo Wear.'’ SNWOO0D : —T ' | I i i i 1 " rSack Suits A customer comes in, looks over the variety of + $1.05 have their money back. to- $1.70 if we made the pants from 50c a pair S5e. . Write for our new illustrated catalogue, “What Ouf-of-town orders filled— write us. 718 Market Street.