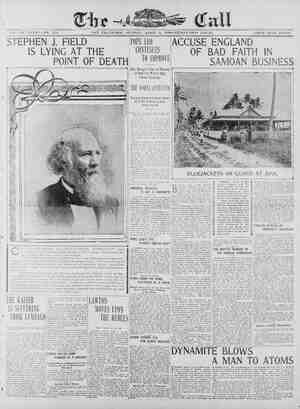

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, April 9, 1899, Page 22

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

rred on & ted positfon an lake, the regre terest t genuine of the incorrob- however, is enty had re- day, and I for a week accomplish of the law g the the oppor- t be very houseled me to d was large of them It was g room where situ- ‘read y ' and looked to t g st exception of a nar- row path wt from the front door and veranda through the trees to the boat nding the was densely covered with maples locks and cedars. A week p by, and the ‘“reading’ progressed ¥. On the tenth day of my solitud thing happened. I awoke after a good night's sleep to find d with a marked repug- room. The seemed to ore I tried to define the like the more unreason- d. There was mething 1 that made me ald. hours I spent in steady when I broke off in the e d for a swim and luncheon not a little alarmed like for stro I was very much surprised, it to find that my dls- room had, if anything, grown ger. Going upstairs to get a book, erienced marked aversion enter aw within 1l the time of an uncom- was half uneasiness sion. The restlt of it nstead of reading, T spent the water, paddling and the most room, a As sleep was an Important matter te me at th I had decided that if my avers 0om was as strongly marked as it had been be- bed down into the ep there. This was, a concession to an fear, but simply a 1 prec: 1 to insure a good night's sleep. I accordingly moved my bed, downstairs into a corner of the sitting-room facing the door, and was morec ver uncommon- ion was completed edroom closed fin- tk ilence and the the room with Iy glad when the ope and the door of the ally upon the shadows strange fear that shared them Outside the night was still and warm. Not breath of air was stirring; the waves were sllent, the trees motionless; and heavy el curt 1ds hung like an oppressive in over the heavens. T seemed to have rolled up with unusual swiftness, and not the faintest glow of color remained to show w ere the sun had set. There was sent in the atmos- phere that ominous and overwhelming ence which so often precedes the most violent storms As the night wore on the silence deep- ened Sven the chipmunks were stilly and the b ards of the floors and walls ceased creak I read on steadily till, from the oomy shadows of the kitchen, came the hoarse sound of the clock strik. ing 9. How loud the sfrokes sounded! There were like blows of a big hammer. I closed one book and opened another, feeling that I was just warmiug up to my work This, however, did not lest long. I presently found that 1 was reading the same paragraphs over twice, simple paragraphs that did not require such et- fort. Then I noticed that my mind be- gan to wander to other things, and the effort to recall my thoughts became harder with each digression Concentra- tion was growing momentarily more dif- 1t Something was ev at work in m sub-conscious There was som thing I had neglected to do. Perhaps the kitchen ndows were not fast- ened. I accordingly to see, and found that they were! The fire perhaps needed attention. I went to see, ' and found that it was all right! When I at length settled'down to my books again and tried to read, I became aware, for the first time, tnat the room seemed grow! cold Yet the day had been oppressively warm, and evening had brought no relief. The six big lamps, o @um'n' ‘“&('W SUT MY .Sl&?.&?l-l BI6 InDIAN mereover, gave out heat enough to warm the room pleasantly. For a brief moment I stood looking out at the shaft of light that fell from the windows and shone some little distance down the pathway, and out for a few feet into the lake As T looked, I saw a canoe glide Into the pathway of light, and immediately CRY | STRETCHED ) BY THE ThReaT S crossing it, pass out of sight again into the darkness. It was perhaps a hundred feet from the shore, and it moved swiftly. I was surprised that a canoe should pass the island at that time of night, for all the summer visitors from the other side of the lake had gone home weeks before, and the island was a long way out of any line of water traffic. My readings from:this moment did not make wery good progress, for somehow the picture of that canoe, gliding so dimly and swiftly across the narrow track of light on the black waters, silhouetted itself against the background of my mind with singular vividness. It kept com- ing between my eves and the . printed page. The more I thought about it the more surprised I became. It was of larger build than any I had seen during the summer months, and was more like the old Indian war canoes with the high curving bows and stern and wide beam. The more I tried to read, the less success attended my efforts; and finally I closed my book and went out on the veranda to walk up and down a bit, and shake the chilliness out of my bones. The night was perfectly still, and as dark as imaginable. I stumbled down the path to the little landing wharf, where the water made the very faintest of gurgling under the timbers. The sound of a big tree falling in the mainland for- est, far across the lake, stirred echoes in the heavy air, like the fir: s of a dis- tant night attack. No other sound di turbed the stillness that reigned supreme As I stood upon the wharf in the broad splash of light that followed me from the tting-room windows, I saw another canoe cross the pathway of uncertain pon the water, and disappear at to the impenetrable gloom tha y beyond. This time I saw more dis- tinctly than before. It was like the former canoe, a big birch-bark, with high-crested bows and stern and broad beam. It was paddled by two Indians, of whom the one in the stern—the steerer—appeared to be a very large man. 1 could see this very plainly; and though the second canoe was much nearer the island than the first, I judged that they were hoth on thelr way home to the Government reservation, LouD ARMS Tp which was situated some fifteen miles away upon the mainland. 1 was wondering in my mind what could possibly bring any Indians down to this part of the lake at such an hour of the night, when a third canoe, of pre- cigely similar build, and also occupied by two Indians, passed silently round the end of the wharf. This time the canoe was very much nearer shore, and it suddenly flashed into my mind that the three ca- noes were in reality one and tfie same, and that only one canoe was circling the island. This was by no means a pleasant re- flection, because if it were the correct so- lution of the unusual appearance of the three canoes in this lonely part of the lake at so late an hour, the purpose of the two men could only re be considered to be in some way connccted with myself. I had never known of the Inc attempting any violence upon the settlers who shared the wild, inhospita- country with them; at the same time it was not beyond the region of possibil- ity to suppose. * * * care to even think of such hideous possi- bilities, and my imagination immediately sought rellef in all manner of other so- lutions to the problem, which indeed came readily enough to my mind, but did not succeed in recommending themselves to my reason. Meanwhile, by sort of instinct, I stepped back out of the bright light in which F had hitherto been standing, and waited in’ the deep shadow of a rock to see if the canoe would again make its appearance. Here I could see and nos be seen, and the precaution seemed a wise one. After less than five minutes the canoe, as I had anticipated, made its fourth ap- pearance. This time it was not twenty yards from the wharf, and I saw thav the Indians meant to land. I recognized the two men as those who had °d be- fore, and the steerer was certainly an im- mense fellow. It was unquestionably the same canoe. There could be no longer any doubt that for some purpose of their own the men had been going round and round the island for swme time, walting for an opportunity to land. I strained my eyes to follow them In the darkness, but the night had completely swallowed them up, and not even the faintest swish of the paddles reached my ears as the Indians plied their long and powerful strokes. The canoe would be round again in a few moments, and this time it was possible that the men might land. It was well to be prepared. I knew nothing of their intentions, and two to one (when the two are big Indians!) late at night on a lone- iy island was not exactly my idea of pleasant intercourse. In a corner of the sitting-room, leaning up against the back wall, stood my Mar- lin rifle, with ten cartridges In the mags zine and one lying snugly in the greased breach. There was just time to get up to the house and take up a position of defense in that corner. Without an in- stant’s hesitation I ran up to the ver- anda, carefully picking my way among the trees, so as to avold being seen in the light. -Entering the room, I shut the door leading to the veranda, and as quick- ly as possible turned out every one of the six lamps. To be in a room so bril- llantly lighted, where my every move- ment could be observed from outside, while I could see nothing but impene- But then I did not « - i trable darkness at every window, was by all laws of warfare an unnecessary con- cession to the enemy. And this enemy, it enemy it was to be, was far too wily and dangerous to be granted any such advantages. I stood in the corner of the room, with my back against the %all and my hand on the cold rifle barrel. The table cov- ered with my hooks lay between me and the door, but for the first few minutes after the lights were out the darkness ‘Wwas 80 Intense that nothing could be dis- cerned at all. Then, very gradually, the outline of the room b me visible and the framework of the windows b 'gan to shape itself dimly before my ey After a few n utes the door (it per half of glass), and the two windows that looked out upon the front veranda, became speci distinct; ana I was glad that this was the anr ), because if the Indlans came up to use T should be able to see thelr oach, and gather something of their plans. Nor was I mistaken, for there presently came to my ears the peculiar hollow sound of a canoe landing and be- ing carefully dragged up over the rocks. The paddles I distinctly heard being placed underneath, and the silence that ensued thereupon T rightly interpreted to mean that the Indlans were stealthily ap- proaching the house. While it would be absurd to claim that 1 was not alarmed—even frightened—at the gravity of the sltuation and s pos sible outcome, I speak the whole truth when I say that I was not overwhelmingly afraid of myself. I was conscious that even at this stage of the night I was passing into a psychlcal condition in which my sensations seemed no longer normal. Physical fear at no time entered into the nature of my feelings; and though I kept my hand upon my rifle the greater part of the night, I was all the time conscious that its assistance could be of little avail against the terrors that I had to face. More than once I seemed to feel most cu- riously that I was in no real sense a part of the proceedings, nor actually involved in them, but that I was playing the part BY ALGERNN “BLACKR?2D of a spectator—a spectator, moreover, on a psychic rather than on a material plane. Many of my sensations that night were too vague for definite description and analysis, but the main feeling that will stay with me to the end of my days is the awful horror of it all, and the miserable sensation that if the strain had lasted a little longer than was actually the case my mind must inevital have given away. Meanwhile I stood still in my corner and walted patlently for what was to come. The house was. as still as the grave, but the fnarticulate voices of the night sang in my ears and I seemed to hear the blood running in my veins and dancing in my pulses. 1f the Indians came to the back of the house they would, find the kitchen door and window securely fastened. They could not get in there without making consid- erable noise, which I was bound to hear. The only means of getting in was the door that faced me, and I kept my eyes glued on that door without taking them off for the smallest fraction of a second. My sight adapted itself every minute better to the darkness. I saw the table that nearly filled the room, and left only & narrow passage on each s I could also make out the stralght backs of the wooden chairs pressed up against it, and could even distinguish my papers and ink- stand lying on the white oflcloth covering. I thought of the gay faces that had gath- ered around that table during the sum- mer, and I longed for the sunlight as I had never longed for it before. Less than three feet to my left the passage-way led to the kitchen, and the stairs leading to the bedrooms above commenced in this passage-way, but al- j— - o — most in the sitting-room itself. Through the windows I could see the dim, mo- tionless outlines of the trees; not & leaf stirred, not a branch moved. A few moments of this awful silence, and then I was aware of a soft tread on the boards of the veranda, so stealthy it seemed an Impression directly on my brain rather than upon the nerves of hearing. Immediately afterward a black figure darkened the glass door, and I per- celved that a face was pressed against the upper panes. A shiver ran down my back, and my hair was conscious of & ten- dency to rise and stand at right angles to my head. It was the figure of an Indian, broad- shouldered and immense; indeed, the largest figure of a man I have ever seen outside of & circus hall. By some power of light that seemed to generate itself in the brain, I saw the strong dark face with the squiline nose and high cheek- bones flattened against the glass. The direction of the gaze I could not deter- mine, but faint gleams of light as the big eyes rolled round and showed their whites told me plainly that no corner of the room escaped their searching. For what seemed tully five'minutes the dark figure stood there, with the huge shoulders bent forward so as to bring the head down to the level of the glass; while behind him, though not nearly so largs, swayed to and fro like a bent tree the shadowy form of the other Indian. While I waited in an agony of suspense and agl tation for their next movement, little cu rents of icy sensation ran up and dow my spine, and my heart seemed alter nately to stop beating, and then start off again with terrifying rapidity. They must have heard its thumping and the singing of the blood in my head! More- over, I was conscious, as I felt a cold stream of perspiration trickle down my face, of a desire to scream, to shout, to bang the walls like a child, to make a noise, or do anything that would relleve the suspense and bring things to a s climax. It was prébably this inclination that led me to atother discovery, for when I tried to bring my rifie from behind my back to raise it and have it pointed at the door to move. The muscles, para strange fear, refused to obey Here indeed was a terrifying complica- tion! There was a faint sound of rattl the brass knob and the door was p h open a couple of Inches. A pause of a few seconds, and it was pushed open stiil farther. Without a sound of footseps that was appreciable to my ears, the two fig- ures glided into the room, and the man behind gently closed the door after him They were alone with me between the four walls. Co! they see me standing there, so still and straight in my corner? Had they, perhaps, already seen me -M\’ blood surged and sang like the roll of drums in an orchestra; and though I did my best to suppress my breathing it sounded like the hing of wind through & pneumatic tube. My suspense as to the next move was soon at an end—only, however, to give place to a new and keener alarm. The men had hitherto exchanged ‘no words and no signs, but there were general indi- cations of a movement across the room, and whichever way they went they would have to nass round the table. If they came my way they would have to pasy within six inches of my person. Whils I was considering this very disagrceabls possibllity I perceived that the smaller Indlan (smaller by comparison) su raised his arm and pointed to the c The big fellow raised his head and lowed the direction of his companion's arm. I began to understand at last. They were going upstairs, and the room direct- ly overhead to which they pointed had been until this night my bedroom. It was the room in which I had experienced that very morning so strange a sensation of fear, and but for which I should then have been lying asleep in the narrow bed against the window. The Indians then began to move silently around the room; they were going up- stairs, and they were coming round my side of the table. So stealthy were their movements that, but for the abnormall sensitive state of the nerves, T never have heard them. As it wa cat-like tread was distinctly audible. Like two monstrous black cats they came round the table toward me, and for the first time I perceived that the smaller of the two dragged something on the floor behind him. As it tralled along over tha floor with a soft, sweeping sound, T some- how got the impression that it was a large dead thing with outstretched wings, or a large spreading cedar branch. Whatever {t was, I was unable to see it even in outline, and I was too terrified, even had I possessed the power over my muscles, to carry my neck forward in the effort to determine its nature. Nearer and nearer they came. The leader rested a giant hand upon the table as he moved. My lips were glued togather and the air seemed to burn in my nostrils, I tried to close my eyes, so that T might not see as they passed me; but my E lids had stiffened and refused to obey. Would they never get by me? Sensation seemed also to have left my legs, and it was as if 1 were standing on mere sup- ports of wood or stone. Worse still, T was conscious that I was losing the power of balance, the power to stand upright or even to lean backward against the wall, Some force was drawing me forward, and a dizzy terror seized me that I should lose my balance and topple forward against the Indians just as they were In the act of passing me. Even moments drawn out into hours must come to an end some time, and al- most before 1 knew it the figures had passed me and had their feet upon the lower step of the stairs leading to the upper bedrooms. There cannot have been gix Inches between us, ar t I was con- scious only of a current of cold air that followed them. ey had not touched me, and I was convinced that they had not secn me. Even the trailing thing on the floor behind them had not touched my feet, as I had dreaded it would, and on such an occasion as this I was grateful even for the smallest mercles. The absence of the Indians from my im- mediate neighborhood brought little sense of relief. I stood shivering and shudder- ing in my corner, and, beyond being able to breathe more freely, I felt no whit less uncomfortable. Also I was aware that a certain light, which, without apparent source or rays, had enabled me to follow g. fol- thelr every gesture and movement, had gone out of the room with thelr de- parture. An unnatural darkness now flled the room, and pervaded its every corner, so that I could barely make out the positions of the windows and the glass doors As I said Fefore, my condition was evi- dently an «bnormal on y for feeling _arprise seeme ams, to be wholly absent. My senses recorded With unusual accuracy every smallest oc- currence, but I was able to draw only the simplest deductions. The Indians soon reached the top of the sealrs, and there they halted for a mo- ment. T had not the faintest clew as to their next movement. They appeared to hesitate. They were listening attentively Continued on Page Thirty-Twao, »