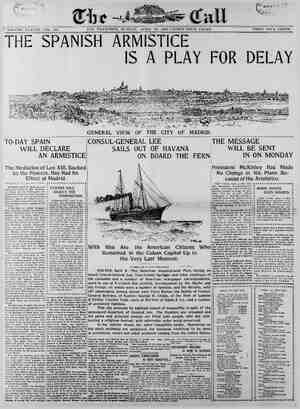

The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, April 10, 1898, Page 28

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

28 THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDAY, APRIL 10, 1898. JUDITH ON HER WAY TJO KiLL HOLOFERNES. Sketched by A. F. Mathews from his well known painting exhibited at the World's Falr. JUDITH AS PRINTED BY DIFE HAT Judith, the heroine of an- tiquity, the deliverer of the be- sieged city, is a character of Bible history that has attracted the at- tention of many artists, is quite evident from the number of pictures of this subject that may be found in the world’s art galleries. A beautiful Jewish maiden who had the atality to conceive a strategy the courage and power to carry it s a subject well worth the effort of st able artist. e is generally represented in the act of leaving the tent of Holofernes, carrying with her, as a trophy of vic- tory, the head of the Assyrian general. One of the finest examples of this I ERENT ARTISTS| representation may be found in the| Pitti Palace, the work of Christofano Allori, a Florentine artist of the six- teenth century. ‘It is claimed that in this picture, which is supposed to be his best prod- uct, the head of Judith is a likeness of the wife of the painter, while the head of Holofernes is supposed to represenl‘ himself. | Allori was one of the foremost of his | school. His pictures are distinguished by their close adherence to nature and the delicacy and technical perfection of their execution. His technical skill is proven by the fact that several copies he made after Correggio have been (taken to be duplicates of Correggio | | himself. In the canvas of Mr. Mathews we find he has deviated from the common | representation by painting Judith as going on her terrible errand. This is a very good example of Mr. Mathews' excellent conception of Bib- lical subjects. His composition Is ex- cellent, his color scheme satisfying, and his drawing is a good illustration of his unusual skill, which Mr. Seymore Thomas kindly szid was unexcelled in | any of the artists of his acquaintance. This picture was exhibited at the | Werld’s Fair at Chicago, where it re- | ceived a great deal of favorable atten- tion. | The subject of Judith is a favored | one with Mr. Mathews, for hanging | very near the one just described is an- | other, a pastel, expressed with much | feeling, and representing the heroine in the act of entering the tent. Here the artist has admirably succeeded in de- picting the strong will and determined purpose that are characteristic of the | woman subject. The pictures may still be seen at the | Hopkins Institute of Art. THE TULIP AS AN EASTER DECORATION GGS in form or other, whether alone or as an adjunct other viands, seem to be a natural article of food for Easter morning and to lend them an in- dividuality appropriate to the occasion gome sli~ht deviation from the ordinary ways of serving them is desirable. The jdea suggested by the accompanying sketch is simple and inexpensive and can be prepared for the meal at odd moments some days in advance. T materials necessary are a sheet of green tissue paper, and one each of pink or any colors e in accord with the al colors of the flower, a box of olor paints, some mucilage and 2 of No. 1 green ribbon. Having cut from stiff paper pat- - and shapes indicated ). 2 of the illustration. % inches wide by 6% long, and represents the long, slender leaves of the plant These should be | cut from the green paper, allowing at | least three for each flower. No. hows the petals of the blossom, is 2 ‘hes long by 4% deep, and each petal | measures 2% inches across its widest | part. | When these patterns are cut lay them issue paper, several folds thick, | ) «zpedite cutting the design, | as many as are needed have | ecured put long, irregular dashes | r color paint on the petals, red | pink on white, etc., as indi- | 3. This work can be done y rapidly and more than pays for | elf in the appcarance of the flower | when completed. When these are dry curl the end of each petal slightly by drawing it over the dull edge of a pair of scissors or an ivory paper cutter, and fold creases in each, as also shown in No. 3. These are ¢ folded around an egg cup, a bit | of mucilage holding the petals togelher‘ some and to the side of the cup, rendering the decoration’ rore secure. Outside of the petals are placed the leaves, which are then tied securely in place by a small bov. of narrow ribbon of green, or in harmony with the flower itself, having first been creased in the fold shown in No. 1 and caught about at the top of the fold with a tiny bit of mucilage. Care must be taken not to cut the petals apart, a mistake it is easy to make, and which wastes paper, time and energy, as it is difficult to put them in place singly on the egg cup, and gain the correct effect shown in No. 4. One of these stoo. at each plate at an Easter breakfast table will cheery surprise to the uninitiated mem- bers of the family, and the egg dis- covered therein is almost sure to have a daintier flavor, so powerful is the ef- fect of our imagination upon material things. GOLD'S CIRCUIT OF THE GOLBE. “A million dollars gold from Japan en route to'the Sub Treasury in New York detained for eight hours at Cedar Rapids.” This very metal, like as not, origi- nated in California, crossed the conti- nent in the form of double eagles, was shipped to London and converted into sovereigns, went perhaps to France, and, after circulating for a time in the shape of twenty-franc pieces, was sent to Japan in payment for silks, and com- pleting the circuit of the earth comes back to us in payment for cotton. The ceaseless ebb and flow of gold around the globe in settlement of trade balances proves that, independent of all statutes, it is by natural laws the money of the clvilized nations. one reflects on the heavy expense of transportation and the great loss from attrition, however, it is surprising that in the age of peace and international Ny wine Ney 18 Ny LONG N2 N4 fSHED OECOMATION FOR AN EASTER BREAKFAST. give a | ‘When | trade relations there has not been es- tablished a world's clearing - house.— New York Herald. | clusfon of his letter Monroe asks Jef- | ferson’s opinion and requests that the HOMAS JEFFERSON wrote to President James Monroe from his home at Monticello, under date of October 24, 1823: | “I have ever looked upon Cuba | as the most interesting addition which icould ever be made to our system of | States.” Monroe had addressed a letter to Jef- ferson, dated October 17, 1823, in which Monroe expressed his opinion that we ought to meet the proposal of the Brit- ish Government, and to make it known that we would view an interference on the part of the European powers, and especially an attack on the (Spanish) colonies,” as an attack on ourselves. This expression preceded the famous “Monroe doctrine” message by but forty days. In that short period, how- ever, Monroe’s impression had solidified into the strong words of his message to Congress, December 2, 1823. At the con- corréspondence be forwarded to James Madison. In view of the talk of an alliance with England, it will be interesting to give enough of this correspondence to show how Monroe, Jefferson, Madison and | John Quincy Adamslooked upon a simi- lar proposal, made when the Cuban question was uppermost seventy-five years ago. In reply to Monroe's letter, Jefferson writes that the question “is the most momentous which has ever been offered to my contemplation since that qg in- dependence that made us a nation. He points out the advantages of ‘“‘detach- ing Great Britain from the band of despots,” and bringing ‘her mighty weight into the scale of free govern- ment.” “With her on our side,” writes Jefferson, “we need not fear the whole world.” But in the next line he de- clares that he “would not purchase her amity at the expense of taking part in | her wars.” | Jefferson declared his position on the | “Cuban question” in anticipation of the | designs of Russia, Prussie and Austria, “g lawless alllance,” says Jefferson, “calling itself holy.” He believed we should “oppose, with all our means, the interposition of any other power, under any form or pretext,” in the affairs of this hemisphere. In thememoirsof John Quincy Adams we find that he, also, was called inlfl consultation on this ‘‘momentous’ question. Adams writes under date of November 15, 1823, that President Mon- | roe sent for him to come to the State Department, where the letters of Jef- ferson and Madison were laid before him. Adams says that Madison’s opin- jon in favor of accepting England's pro- posal is ‘“less decisively pronounced (than that of Jefferson), and he (Madi- son) thinks as I do, that this movement on the part of Great Britain is impelled more by her interest than by a princi- ple of liberty.” i The full text of Jefferson’s letter is as follows: * MONTICELLO, October 24, 1823. Dear Sir: The question presented by the letters you have sent me Is the most momentous which has ever been offered to my contemplation since that of in- dependence made us a natfon. This sets our compass and points the course which we are to steer through the ocean of time opening on us; and never could we embark on it under circum- stances more auspicious. Our first and fundamental maxim should be never to entangle ourselves in the broils of Eu- rope; our second should be never to suf- fer Europe to interfere with Cis-Atlan- tic affairs. America, North and South, has a set of interests distinct from those of Europe, and peculiarly her own. While the last is seeking to become the domicile of despotism, our endeavor ghould be to surely make our hemis- phere that of freedom. One natlon, most | of all, could disturb us in this pursuit. | She now offers to lead and accompany us In it. By acceding to her proposition | we detach her from a band of despots. bring her mighty weight into the scala for free government, and emancipate a continent at one stroke, which might * otherwise linger long in doubt and diffi- culty. Great Britain is the nation which can | 'WH T was the season of Easter along the Eastern 8hore of Maryland, and that favored land, though the war was on between the States and the Blue and the Gray were flercely contending for a principle which could be settled | only by bloodshed, bore every evi- | dence of nature that it was in truth what | its people called it, “God’s country.” Lying low and level, fresh in the spring green of its fields and orchards, shining in the silver strands of its myriad streams, stretching back and away from the rippling waters of the Chesapeake un- til its clumps of woods rested on the east- ern horizon and lazily luxurious in its balmy climate, it was. as it still is, a land of peace and plenty, fit for the restful quiet of body, soul and mind. As one of its songsters quaintly sings: “‘Here terrapin and canvasback Are to the manner born; And here the nectar of the gods Is rye instead of corn.” ‘With Easter had come rejoicing among the dusky denizens of kitchen and cabin along the Eastern Shore, for Easter was the darkies’ festival in those days, and | at no place was there more joy than | among the blacks of Kirkham Manor, for Major Winter, the proprietor of the manor, was a kindly master, who let the | fetters rest lightly on his slaves, and he had announced that each of his people, | big and little, should have a ticket to the circus which was to show in town on the Monday after Easter. It was not always that a circus was one of the Easter fes- | tivitles, for Easter sometimes came be- | fore the circus bloomed, but in the year of this chronicle Easter nad fallen after ! the middle of April and the circus people { had hastened to be ready on the Monday after. True, it was not a circus of the old-time splendor, for the war had made that impossible, but there was a big white tent and spotted horses and ladies in tin- sel skirts as short as they were glittering, and there were hundreds of other fairy delights that grow in simple minds from the pictures on circus bills. But the circus was only part of the | richness of the time. Alli work was to stop at noon on Saturday, there was to be church and ribbons and the best bib and tucker on Sunday and on Monday and Tuesday following the white folk were to take hold of the work about the house and place and let all the darkies In the county go to town to have their full of ty. Cake walks feasts and bar- becues and weddings and hoedowns and frolics of all kinds were in order, winding up late Tuesda t, when even if some came home drunken it was not held against them as an offense. And how they did enjoy it. It was free- dom to them, without any of its respon- bilit, fe, and th ,‘or ‘g.o;g:"rf"u oxm? that i‘h".“i"fli Y THE EGGS WERE GHANGED | FROM GRAY TJO BLUE. yet come, which is the true darky phil- osophy. Even C on the It was Manor w it was Mejor bor's hristmas was not such a season stern Shore as Easter was. aturday afternon and Kirkham s deserted of servants. Indeed, most_deserted of all humani wwter had ridden over to A eigi immediately after dinner at 1 o'ciock, and no one was about except the major's only daughter, Kate, who had chosen to stay and color a bushel or two of eggs for the children. Kate Winter was the pride of the n-ajcr's heart, she was the mistress cf cvery man's heart if she chose to be. Juat’ . bright of mind and ey2. yuick of tongae and motion, kindly withal and beautiful, it was her right to tule, and she did. When the war had com?, her conservative father had taken no decided stand, but the high strung Kate was posi- tive she knew which side was right, and at once announced herself. She was for the South, and what an unmitigated little | rebel she was. The sight of a blue coat made her eyes snap and a single strain of “Yankee Doodle”” put all of her nerves on edge. Yet during the month of Janu- ary, last past, whicn she had spent in the social whirl at Washington, the one man who was most devoted to her was Captain Leonard of the Federal army, and, woman-like, the man she most wished to be so was L..s same captain. When she came home, the captain acted as escort to her party as far as Balti- more; a few weeks later he had come to Kirkham Manor for two days: he had come again late in March, and now he was to spend Easter Sunday and Mon- day on his third visit. Just why she per- mitted these attentions, she could not say, for the captain wore the hated blue, and he was, in addition, a lumbering, awkward, good-natured, simple, sincere kind of overgrown boy that a woman likes better than anybody in the world, but doesn’t think of loving as she might love a husband. As for such a man, himself, he rarely is conscious of his good Eolntu. and failing in the tact to present imself as he should, all the chances are that married life with the woman he gets will not be what he had a right to ex- pect it to be. “He's a Yankee, Kate,” her father would say of the captain In a bantering mood. “‘He {8 a Leonard,” she would retort. “HIs ancestor was _Jonathan Leonard, brother-in-law of Lord Baltimore. Is| mine any better?’ and Kate would smile, because her father was a stickler for family. “'All the more reason why he should not ‘wear the blue,” argued the major, accom- &anled by a strain from “Maryland, My aryland.” e Well, papa,” with a toss of her head, ‘what do I care? I am sure he is noth- ing on earth to me. I met him as I met dosens of others, and if he wants to come down here to :u us,” e‘m h::mn% the us—‘‘we can not very well shut our doors against him. He is & friend, or says he is, and I don’t want anvthing to be nearer, SAID. do us the most harm of any one, or all on earth; and, with her on our side, we need not fear the whole world. With her, then, we should most sedulously cherish a cordial lflendshlfi; and noth- ing could more securely knit our af- fections than to be fighting side by side, in the same cause. Not that I would purchase even her amity at the price of taking part in our wars. But the war in which the present proposition might engage us, should that be its conse- quence, is not her war, but ours. Its object is to introduce and establish the American system of keeping out of our land all foreign powers; of never per- mitting those of Europe to intermeddle with the affairs of our nations. It is to maintain our own principle; not to depart from it. And if, to facilitate this we can effect a division in the body of the European powers and draw over to our side its most powerful member, surely we should do it. But I am clearly of Mr. Canning's opinfon that it will prevent, instead of &l:ovoklng war wit) Great Britain. ithdrawn from their scale and shifted into that of our two continents, all Eu- rope combined could not undertake such 2 war. For how would they propose to get at either enemy without superior eets? Nor is the occasion to be slight- ed which this proposition offers to pro- test against the interference of any one in the internal affairs of another, so flagitiously begun by Bonaparte, and ny continued by the equally lawless alliance calling itself ‘holy.” But we have first to ask ourselves a question. Do we wish to acquire to our own confederacy any one or more of the Spanish provinces? I cordially confess that I have ever looked upon Cuba as the most interesting addition that could ever be made to our system of States. The control which, with Florida point, this island would give us over the Gulf of Mexico and the countries and the isthmus bordering on it, as well as those whose waters would flow Into it, would fill up the measure of our po- litical well being. Yet, as I am sensible that this can never be obtained, even ‘WHAT THOMAS JEFFERSON ABOUT ANNEXING CUBA Copy of the Famous Letter on the Important Question That He Sent to James Mon- roe Seventy-Five Years Ago. with her own consent, but by war, and its own independence, which is our sec- ond interest (and especially its inde- pendence of England), I have no hesita- tion in abandoning my first wish to fu- ture chances and accepting its independ- ence with peace, and the friendship of England, rather than its association at the expense of war and her enmity. I could honestly, therefore, join in the declaration proposed, that we alm not sessions; that we will not stand in the tween them and the mother country, but that we will oppose, with all our means, the forcible interposition of any other power, as auxillary, stipendia or in any other form or pretext, and most especially their transfer to any power by conquest, cession or acquisi- tion in any other way. 1 should think it therefore advisable that the executive should encourage the British Government to a continu- ance in the dispositions expressed in these letters by an answer of his con- currence with them as far as his au- thority goes; and that, as it may lead to war, the declaration of which re- quires an act of Congress, the case shall be laid before them for consideration at their first meeting and under the rea- sonable aspect in which it is seen by himself. I have been so long weaned from po- litical subjects and have so long ceased to take any interest in them that I am sensible that I am not qualified to offer opinions on them worthy of any atten- tion; but the question now proposed in- volves consequences so lasting and ef- fects so decisive of our future destinies as to rekindle all the interest I have hitherto felt on such occasions, and to induce me to hazard opinions which will prove only my wish to contribute still my mite toward anything which may be useful to our country, and pray- ing you to accept it only at what it is worth. I add the observance of my con- stant and affectionate friendship and re- THOMA! spects § JEFFERSON. JUDITH WITH THE HEAD OF HOLOFERNES. From a photograph of Allori's great painting. that's Yankee. But I do wish sometimes that 1 s a man so I could fight Captain Leonard.” Kate was fully in earnest, too, and her father was careful not to banter too far, | seeing that he had done so once to his great discomfort, for the pretty Kate was not all angel. In the midst of the egg coloring Aunt ¢, the cook, came hurrying to the as fast as she could. Fo' de Lawd, Miss Kate," she puffed, “I done seed de Cappen a-comin’ an’ I knowed you wuzn't especkin’ uv him fer two hours yit, so I jis run up f'um de | awchid to tell you an’ gib you a chance | to spruce up a little 'fo’ he gits yer.” But it was too late, for even as Aunt Mary was performing her errand of mercy, the captain rode up to the house and he saw Kate at the kitchen window as he swung round the corner of the lawn. As Aunt Mary had said, he was hours ahead of time and Kate almost lost her temper at the promptness of the man, for there was no one on the place to re- ceive and entertain him except herself and there was no escape. He had stopped beneath the shade of a large tree in the yard and there Kate, like a true house- wife in her working attire, appeared be- fore him with a basket of eggs and color- ing paraphernalia in her hands, and the captain thought he never saw her look- ing half so pretty. That he was in love with her needed no angel come from heaven to proclaim to all the Eastern Shore. It was in his eves, his face, his hands, his voice, his manner. two | | As she met him now, laughing, she told him she was just about to color a dozen Easter eggs for him to take back to Washington, but he had come too soon, and they were not ready. | He might have turned her remark nicely by saying something about the impossi- bility of seeing her too soon, but the cap- | tain was too awkward for that. Instead he said, as he pointed to some colored cloth in her hand: “What color will they be, Miss Kate?"’ “Gray,’ she responded promptly and much to his surprise at her interpreta- tion of his innocent question. “It is my color, Captain Leonard, and to be Knight of this lady you must wear the color she gives you. But why did you come so early to stop me at my work?" she added, still lightly enough. *“Papa was expect- ing to return in time to meet you and do {the honors, but here you are and what is ever to be done with you?" She looked at him ruefully, and he smiled, but there was a shadow in it. “It was my only opportunity, Miss Kate,” he replied seriously. “I am ordered away to leave Washington on Monday and join my regiment before Richmond at once. Men are needed there, and I am only too glad to be able to do what I can for my country.” The lines in Kate's face grew hard at his words, and she looked at him as if she would speak as she had often spoken before, but she restrained the first fm- pulse and waited for him to go on. “I thought I would like to See you once more before I went away,” he continued way of any amicable arrangement be- | at the acquisition of any of these pos- | | disappeared; lhl! arm around her, firmly, and | | | and for a minute continued in and then with a half .m!lsi oated fellows o e abant chmond have oaied fellows hgjunily. “You know yon?rs down there about RI vay ing us blue c a way of shooting (Saated el ws in a most inhospitable fashion s?blfl\- T won't be able to come’ back here When I get through down there. You know, Miss Kate, war is,so uncertain in some respects.” He wupta.lking just to be talking. Kate knew it and she could not endure the of it. th‘?l‘;gg’tt do that,”” she almost shouted a him, and she hysterically dropped the basket of eggs. war had never been pre- gented to her in quite so red a light be- ore. “Oh, oh, Miss Kate,” exclaimed the captain, stooping fdo:n toegll(ck up what might be saved of the wr & “‘iet them be,” she cried, snatching at him. “What are a few eggs to & human 1 : Whose, Miss Kate?’ he said, stu idly. “Why, vours,” she rattled on. Ypoul'l, Didn’t you say vou were going to that horrid Richmond to be shot? And is that nothing?"” s Tt Wasnt very much, Miss Kate” he answered In his slow way, “in view of the fact that, according to your owid statement, your soldiers Kill about fm:ty of us to our killing one of them; so I'm only a fortieth. That isn’'t & great deal, is it?” “If you don't stop talking that wav, Captain Leonard—"" Kate began, but she could not finish the sentence, and, slttlné down on the rustic bench, with the bask of broken eggs at her feet, she buried her | face in her hands. This was a phase of the affair thllg could not ordinarily have presented itsel to the dull mind of the captain. But now it came to him as a revelation from on high, as the light fell upon Saul of Tars sus. In an instant his awkwardness ha his boyishness had devel- ly out of itself; he was & he was a.lrea.d_\"dn. s:eltl:)e‘:‘. 2 e, by Kate's si tn the instinctive confidence that comes under only one condition. = “Kate, my own Kate, oped sudden man now, as and sitting down he said first, the n‘:nlle strain, Then he stopped, and Kate shyly litted her face from her hands and looked at him with that in her eves that was never there till now. o e . . i An hour or so later the major came TICc ing up and as the captain rose (ofmefi him, and go for his own horse. f(r ; was now time to be starting b:}f 5 0 - Washington, he stumbled against the egg e that the “What color did you say, dear, g eggs were to be?” he as ed witl o little smile in the corners of h'ls mo “Blue," she answered, proudly. s And the captain rode away that svenheg to return later as a_colonel: and Wheg the war was over the papers (pB\:ll ed glowing notices of the marriage O ng dier-General Leonard . and Miss s Manor, and the time! e W slMeTON: LOSS OF LIFE " AMONG INFANTS HE Medical Record says: “The fact is well known to medical men that where infants are massed together in large numbers their chances of living are immensely diminished. Convineing proofs of this have recently been afforded in the case 0'5 foundling hospitals in Italy and France. There is no need, however, to go abroad for confirmatory evidence. At the Randall’s Island Foundling Hos- pital, an institution supervised by the New York Department of Charities, of 368 infants under six months of age received during 18% and treated continuously only 12 remained alive April 15, 1897. The aver- age duration of life of the 354 who died was between five and six weeks. The death rate was 9.7 per cent, and only two of the survivors were bottle-fed. A few historical comments will empha- size the needs of foundlings. Up to within three decades practically nothing was done for them in any English-speaking country. In England under the poor law of 1834 the young “were merely received to die, and the few who struggled into lite were trained only in ignorance, idle- ness and vice.” In Philadelphia, until 1885, all waifs were sent to the foundling ward of the Philadelphia Almshouse, where the death rate was practically 100 per cent. In New York, only a quarter of a cen- tury ago, the child who was not at once destroyed by the despairing mother had no alternative but a lingering death in the almshouse under the care of aged pau- pers. Reports show that of the infants so placed scarcely one ever survived. At the present time, except in New York city, Philadelphia and in Massachusetts condi- tions remain the same. Michigan has its placing out system for older children, and Minnesota and other States are helped by well-organized chil- dren’s aid societies. But except in Massa- chusetts very little effort has been ex- erted to change a system which at best seems only a legalized form of infanticide, We must, of course, except the purely lo- cal and unorganized individual kindness which has always in some measure, but very inadequately, coped with the need. The New York Foundling Asylum on Sixty-eighth street shows how needless and how criminal is much of the mortal ity among foundlings. Its origin is due to Sister Irene, whose fame is national In 1869, with only $5 in her pocket, she began the work by placing a little erib outside the door of her small house on East Twelfth street. That crib now stands within the present magnificent bufldings of this charity, and on the af- ternoon of February 21 received its 30,091st temporary occupant. The system as evolved by Sister Irens and carefully continued by others since her death consists in paying a foster mother from among_the respectable poor to care for a foundling, as well as her own babe. The care ceases at the end of three years and children are then returned to the asylum for kindergarten work and schooling, until finally placed in good familles the country over. In a special interview with Sister Teresa Vincent, the present superintendent, the g%llo;fing noteworthy statistics were se= red: In 1892, of the 2891 children of vario ages cared for, 611 died, an average ‘;: 223 per cent; in 1893, of 2962 there died 596, an average of 20.1 per cent; in 189, of ?Ootth?re died 573, an average of 24.9 per ent. In relation to the most recent 360 deaths it is interesting to note that 9 of thosa who died were received under one year of age, while 128 of the fatal cases were received between one and two; showin; that while under the Randall’s Islan barrack system it is almost certain death to a mere infant to place it there—in the Foundling Asylum its chances are better than if kept for a while in neglect and hunger and ill treatment by its mother, THOMAS JEFFERSON. maasure 9 w."/u&&a/ well- Ma BMMMMLMMM@WI-- o wre itk G acquine T oo orm m-/ib-qmwmwrn,";fl. S,.M/,—mm? ,wukd,anfwmf Kase esor lockad on Cba 04 Ha sl imderesbing addihon thasheaulst ecrer fam mada T o syatorn o stokes. W comlonal S anh Tl prosoll Hhia cstomd wvw(l,uuuw“a. Wflflm,md'fl(w&flflfl’ ,Mf‘auw"" e Maimed, erom R har sum conserk, bul-by warr: amdt Ao orndepamoamen, ek e sesamat- o eea s aspssally 1 mdapirdamca o I harel) * com be secunad crtbholt A, Jhave ne mewfimlw‘ ZE/M chameet, amd Muf“.fl\s £'s imBapromdames wth peoca, yw‘"‘lh‘fl‘! L e FAC-SIMILE OF PART OF THE LETTER THOMAS JEFFERSON SENT JAMES MONROE IN OCTOBER, 1823, TOUCHING THE ACQUISITION OF CUBA BY THE UNITED STATES. : L]