The San Francisco Call. Newspaper, December 29, 1895, Page 24

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

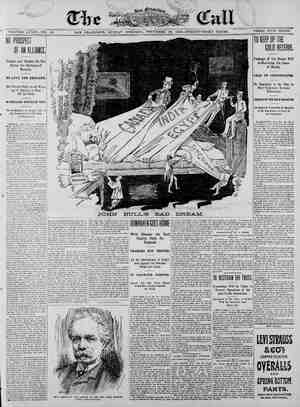

THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDAY, DECEMBER 29, 1895. that a glorious Christmas, rding to some of Santa Ciaus’ par- ight came at least an hour asted at least an hour later s any time this winter. It is e that the almanac does not ny such statement as that, but ‘thing bappen on Certain it is that the sun got and early, and blazed away all he went down in a blaze of t would have made one of Tur- e .and washed out. 0ld Sol wasn’t a ance to the blazing of the Christ- the most gorgeous that ever olks and little. v had all been dragged out of the nd the churches and the hallsand 1 one big field they would made a reg forest, thuse Christ- tdn’ it havé been a gorgeous t lost in, though! andles would have made any 1 enough—surely. would have been plenty to lenty to wear, and plenty of children to play with. Lost in s trees! 1t would be like that girl has of being shut up in a e of gingerbread, with win candy, and with everything 2'of icecream or plum- kind of ca And in eam nobody ever k how to get at house without eating every bit 1 that every boy and —awfully nice, and For w if vou able to eat everything, and saten so much vour stom- dn’t do anything mere get out to wake your d to smother 1 a gsyou couldn’t eat? t in a forest of n co t even and there, you know, and you ound and shout, and build res and everything. the I bega keep it up a little while as not. Some of vou have dozens of things you 't be too sure either, my dear nta Ciaus only neglects the ren. n old rascal, that Santa (v, |uite favors people who already have plenty of things, and brings gifts when they d least. to have the things dn’t wonder a bit. ks it is best to teach ttle children what a joy itis other people happy, and so he away. nall folks who have £0 on giving them 3 dren a secret that es to talk very much about. 1 There are thousands of children right | him and found him sitting on the foor here in this City who didn’t have a Christmas present. If you don’t beiieve that—and I wouldn’t if I were you if I could help it—if you | single | surrounded by his treasures, saying to | himself, *‘No, T just can’t give a single one | of them back to Santa.” “Well,” said mamma, ‘“‘what are you go- don't believe it just go right up and ask | ing to do, darling?” Mrs. McFee of the Salvation Army. You | “Mamma, I guess I don’t care for a tool- might as well take an armful of things | box this year.” with you when you go, and when you have heard some of the stories that are too sad and too commonplace to put in the paper vou will want to go home and get every- thing else you own. People even die on Christmas you know, though it seems a shame to speak abou it dear father’s funeral the day before Christ- mas. They’ve got a little delicate mother to take care of, have these children, and they love her just as tenderly as you co your mothers—any one or all of you. And those children and their mother haven’t a dollar in the world. Christmas presents? They didn’t know it was Christmas I verily believe. Somebody told them probably, and they must have seen other people busy and happy about it. But for themsely vell, their father was dead. It was as much as they could do to re- member that there wouldn’t be anything to eat in the Louse but for kind strangers who had found therm in their trouble. If itis a shame to remind you of such grief and pain, dear children, it is kind too to give you a chance to 1 B it. you can’t do anything else Joving thought to sorry littie souls who are sure to be reached i e e THE DONALD SERIES—NO. 9. FOR TINY BOYS. Dear old Santa brought to Donald every- | thing the little fellow wished for buta cowboy suit and a toolbox. He was perfectly satisfied to give up the cowboy suit beca taken him throu, all the large stores where Santa keeps his toys, and the kind clerks told him that Santa Lad ali kinds except cowboy suits. pretty sure that next year the good old fellow will have them too. But the tool- b Oh, how disappointed he was when h not find it among his presents! He asked his mamma why Santa Claus did not bring it to him. “Well,” saia mamma, *'I think Santa was afraid 1t would get trouble than it would give you pleasure; but perhaps if you wish it so badiy we can give Santa your beautiful long train of cars in exchange for a toolbo. “Oh, no. I just love my st said. without thinking one bit. “Well, then,” said mamma, “you choose which of your gifts that kind Santa sur- prised you by sending, thouch you did not ask for it, you would be willing to give up, and I shall write a letter to Santa asking micars,” he him not to feel too badly that you are not | satisfied and to please change the toy which you send for a toolbox.’” The little fellow went to the playroom with a very serious face. | “All right,” said mamma, *‘and remem- ber, my dear little son, that it is not best for tiny boys to have everything they wish even at Christmas time.” | arsiesds < children that I know went to_their | And if | ou can send a | ind helped by that. ! e his mamma bad | Now Donald feels | rou into more | ; | CONFESSIONS OF A BAD BOY. It was a cloudless day, that 31st of De- ceml in the early sixties, when I took first ride in a train. | The steam cars, as they were called, had been running but a short time in Oakland | and were making only two or three trips a day. I bad a great desire to ride in the cars, | for, to my verdant mind, they were super- natural. My uncle, with whom I resided, lived about a block from the railroad. He was | serious matter. Often he tried to impress upon my mind the danger of my being on the track when a train was due. Many times a day I would run down the street to see if the whistling iron horse | was in sight. If not, I would put my ear on the rail and listen, as I bad heard that | it would signal its approach by making a rumbling noise. Often I would sit in the shining sand | and wait for the train to pass. I would amuse myself by digging deep holes in the sand. Taking up a -handful, T would slowly open my fingers and let the grains drop through into little mounds, which I would play were people and would give names to. If I were not at the corner when the locomotive came puffing down the track, I would skip through a cloud of dust to where I could watch the strange and noisy engine, with its cumoersome yellow coaches, until they turned the bend and were lost to my view. | youthful eves was a diminutive one called Liberty. Standing in front above the cow- catcher was a figure of a negro holding the American flag in his right hand. It was made of iron and painted in brilliant | colors. The man looked as if he were on strike and was always just going to jump off. T had a chum about my own age (9 years) who was as much interested and as anxious as I was to ride in those cars. | We had often talked the matter over, and | decided that we could watch and wait, and whenever we heard that any member | f either of our families was going to San ancisco we agreed to let each other know and to be on hand to follow. I was always on the alert, and one morn- ing my vigilance was rewarded. I learned that my uncle was going to cross the bay that day with his turkeys, which he in- tended to sell in the City. Now this wasa | golden opportunity not to be missed, for | Santa Claus, that wonderful and mysteri- ous personage, had his headquarters in In about half an hour mamma followed | San Francisco in those days. “NO, 1 JUST CAN'T GIVE A SINGLE ONE OF THEM BACK TO SANT. A,”” SAID DONALD, a conscienticus man, without children of | bis own, and he had found my training a The engine which most delighted my | To scamper off to the home of my chum | took but a few minutes, as he lived within two blocks. I was at the aepot on time, and had to keep up a continual dodging to keep out of the way of my guardian. Jackie, my chum, was slow in putting in an appearance and I wasalmostin despair. At the last moment he came rushing down the street, closely followed by his two yonnger brothers. We did not have time to get rid of this most unwelcome contingent, for the bell was ringing and the train moving as we jumped upon the platform of the last car. Jackie grabbed one of the youngsteis and Ianother. I jerked my burden up on to the first step. The little chap had run pretty fast and was breathless and hatless. The button- holes in his trousers were too big for the buttons on bhis little calico waist. The two parted company, and as I dragged and tugged to get that infant up the steps to the platform the kaleidoscopic effect was certainly comical. We run- aways believed that we could enjoy our ride better by remaining on the extreme end of the train. So we all sat in a bundle | on that platform and held the iron railing | with & firm grip. It was a delightful ride | through the woods. We stopped now and | | then-to take up a passenger, then went | | lying along past the trees and stations till ] | we came to the long bridge. This was un- expected. It was entirely new to us, and l our spirits sank considerably as we rode over the water. We never thought of ad- miring the beautiful bay, nor the green hills pack of Oakland. Our tboughts were at home. The younger members of our party did not try to control their feelings, but screamed vociferously for their moth- ers. When we reached the wharf we were glad to alight, and nobody minded the red-faced brakeman who grinned at us and asked us whether we thought we were an escaped menagerie, We were surprised, annoyed and disap- | pointed wnen we found that we could not | g0 aboard the boat without tickets. We | had supposed it was only necessary to | push right o | While Jackie-and I were discussing the situation the passengers were going on the | boat, Willie was sucking his thumb and | Eddie was crying over his trouble with buttons. All at once a couple of cold, hard fingers | | caught my ear and a stern voice with a tremor in it iurred on the solemnity of the | scene by exclaiming: A CALIFORNIA BABY SMILING IN FOUR DIFFERE T WAYS. [Reproduced from a photograph taken for “The Call.”’] ‘Whistles blew as if to crack their cheeks, and the bells clanged and cianged again. My uncle opened the door to listen. “I wish the boy was in here by the fire,” I heard him say, and I saw my aunt in her rocking-chair before the fire and cry- ing softly. sitting there that I must have forgotten to hold on. Something made a qeeer little sound, something fell through the air, and in a minute my uncle had me lying there before the fire, but with a broken arm. You may be sure L had plenty of time | to make ‘good resolutions for that new year. that is another story. At any rate 1learned a lesson that lastea me. And I want to advise you, boys, a [Photographed from life for “Th TRYING IT ON THE BABY. e Call” by Theodore Scherwin.] here?”’ 1did not attempt to explain, and my car felt as if it were being puiled from my | head as I was marched intoa car. My frightened and disappointed little companions in crime followed, and we were put into a_car and told to stay there. The return trip was not as pleasant as we had anticipated. My uncle accompanied us, and he scolded | and scowled with every turn of the wheels. When we reached our station I parted from my friends. When we were at home again my uncle told me quietly to prepare to receive cor- rection. He then left the room in search of my aunt, and I disappeared from the house in | a twinkling, oniy to bob up in a moment high up among the branches of a large oak tree which shaded our door. My uncle came out, saying, ‘‘He has run away, but I shall soon find him,” and he shut the front gate with a terrible clang. Presently my aunt followed him, tying her honnet as she went. When the coast was clear I climbed down. 1 went into the house and gota flour sack, into which I crammed food. This I fastened to a rope and pulled up to my retreat. I also hauled up into the tree two flat boards and a blanket and pillow. I felt very proud of my fort and thought I could stay up there as long as I liked. My aunt and uncle came home talking | anxiously, and I laughed to think what fun it would be to bring them to terms. It grew dark presently and then cold— colder. I was very tired and soon fell asleep clinging to my ropes and boards. Horri- ble dreams came to torment me, and I thought I was being torn limb from limb. The misery of those hours I shall never forget. Too obstinute to go down I shiy- ered and ached and wept. ’ In the depths of my naughty little heart T must have been sorry and ashamed, but I could not give up yet. After a while it Eegan to rain forlornly, |and my cupof woe seemed full. Still L waited on, feelinz that a great principle was at stake. After interminable hours of darkness the bells rang out all at once. “You young scamps, what brought you l little out of a wisdom born of experience. When you wish to escape consequences, or an enraged uncle, do not climb a tree. A. B. S. - BLUE-EYES AND BROWN-EYES. She stood looking in at one of the shop windows a little off Market street, a pale- faced, puny little creature in cotton gown, coarse shoes and rimless hat, looking with hungry beseeching eyes at the heaped-up toys, and once in a while reaching her small hands out convulsively, as if just te | touch them would be Christmas enough for her. The lad whose tingers held her gown was a wee little fellow, all dimples and roses, with rings of flaxen hair tumbling about his eyes, and his cheeks were round and kissaple as any child’s could be. Evidently, whatever of good his home could give was lavished upon Blue-Eyes, for his appearance was in striking contrast to that of his sister. “Bobby,” said Brown-Eyes, half under her breath, “if only you could have one of those be-a-u-tiful horns—just the little one up there that shines so! Wouldn’t it be fun to make it cry all sorts of things? Eh, Robbie?”’ *‘No, I hate borns,” answered Blue-Eyes. “They make mamma’s head ache.” But, all the same, the boy was looking at the big and little tooters in the window with eyes that seemed not to agree with his words. “I wish,”” he went on presently, *T wish you could buy some of those cakes over there and eat every one of ’em yourself. You gave all your breakfast to me, I know, and your supper, too. You’'ve done it lots of times, and mamma says you’ll starve. That’s what makes the big hollows in your cheeks, she says. And— and— I don’t want a horn!— nor Chrstmas, nor— nor anything!”” But there were little hints of tears in the blue eyes. “Why, Bob, you know I never get very hungry, as you do”’—there was a quaver in the girl’s voice that she could not quite repress—‘‘and at any rate, boys have to be She looked so like my mother | As to whether I kept them or not | fed a great deal, they grow so fast. Look, Bobbie! See—" But the girl said no more, and in a| the truth came out; how two stories were told amid tears and laughter and a happy future planned for. But the children’s | minute, all in a tumbled liftle heap, she mother and the children’s friend were in- fainted dead away. What a scream’it was that Bobbie gave! | No horn could have been heard so far, at | least so_thought the man who had carried | Brown-. | sprinkl | white, still face that looked so | the gaslight. ““Is she dead ?”” wailed Bobbie. | “Wall, now, [ reckon not,” replied the | man; “but see here, youngling, yoa;xl;e as at’ )¢ water now and then over the pitiful in | great on the howl as a coyote. | your name?”’ “Bobbie, but mamma calls me Blue: Eyes.” The brown eyes were open now, and the timid little creature, who had indeed faint- ed from hunger in the midst of Christmas plenty snd Christmas cheer, reached for | her brother’s hand, saying feebly : “We mukt go now, Bobbie.” “She’s hungry, she is,” whispered Bob. *‘Hungry! River of Jordan! and you don’t say so!”” but he was examining the iace of the gizl critically as he spoke, and something he saw there gave a strong tug at his heartstrings and set to playing all the fountains of memory as weil as all the sympathy of man ‘toward helpless womanhood be it in ever so slight a form. *What is your name ?” he asked abruptly. “Jerusha Ellen Ford, but mamma calls me Brown-Eyes.”’ ““‘Jerusha Ellen?” an odd name. I never heard but one person called that, and she was my sister. "I came out here in ’55,” turning to the shopkeeper, “all the way from Maine, 'round the Horn, and up in "the mines, tryin’ my luck here and | there, and—well—1 reckon I know what hunger means, the cantankerous beast! Where do you live, Brown-Eyes?” “T’Il show you,” said Blue-Eyes, and off they went together, the girl walking feebly. Presently the good man hailed a hack, put the children within, jumped in him- self, after giving orders to the driver, and | when that hack stopped at last at the children’s poor home on Shipley street, a | good many packages, that looked sus- | piciously like Christmas, followed the ! party up the shaky steps and into the poor | room where Mrs. Ford received them, | wondering if the world was indeed come | to an end, and she safe in heaven with her | babies, or if she only dreamed. | " “TLook! look!’ cried Robbie, and “O | mammal” said Jerusha, now quite recov- | ered. **He has been so kind—so kind— just like papa. He made us eat rolls and | real chicken all the way home,” ““And we rode in a carriage, too. like rich folks,” interrupted Bob. do you think of that?”’ ‘Well, I haven’t time to tell you just how just “\\Jhub was lying upon the pavement, having | ves into the little shop and was | deed sister and brother, and God had made | their paths to cross that blessed Christmas eve. | _ “It was the name that struck me,” said Mr. Ellwood after they were all gathered around the bright fire in his hotel a little | later in the evening. ‘‘It’s an uncommon | name, you see. and not overly fine. And then, something in the kid’s face brought you back to me, just as I saw you last, a | baby, almost, in the old home down in | Maine. E “Yes—I ought to have written, I know; ut for years I'd nothing good to write, and then—well, I didn’t. God forgive me.” ““You must be awfully rich now, uncle.” said Bob, who stood leaning upon the table, piled with Christmas toys. “Well, an English company bought one of my mines last week and I've $20,000 in the California Bank. Put it there yes- terday, and I didn’t know who for, did I, Brown-Eyes?"” And Bobbie sang: Sweets for the Christmas! And h olly and holly, And bells ringing merry and cleer, ADd won't it be jolly,aud won't it be jolly When Christmas comes twelve times & year? S g o DREAM MARCH OF THE CHILDREN Wasn't it a_funny dream?—perfectly bewllderin’? Last night and night before, and night before that, Seemed Iike I saw the march o' regiments o' chil- dren, Marchin’ to the robin's fife and cricket's rat-tae tat! ‘Where go the children? - Traveling! Traveling? Where go the children. traveling ahead? Some go to kindergarten, some go to day-sch Some go to night-school and some go o bed ! 00l, Smooth roads or rough roads, warm or winter weather, On go the children. towhead and brown; Brave boys and brave girls. rank and file tozether, Marching vut of babyland, over dale and down. Some go a-gypsving out in eountry places— Out through the orchards, with blossoms on the oughs, Wild, sweet, and pink and white as their own glad faces, And some go, at evening, calling home the cows. Where go the chiidren? Traveling Where go the children, tra d Some go to foreign wars und camps by t Some g0 to glory 50, and sonie go to bed ! Traveling! firelight, Some go through grassy lanes leading to the city— Thinner grow the green trees and thicker grows the dust; Ever, though, t0 little people any path is pretty So {tleads to newer lands, as they know it must. Some o 10 SINZINg bees. some Some g0 10 thinking ove Some go a-hungered, but Where o the childrs ‘Where o the chil Some g0 Some g0 to dream t and some g0 o bd ! JAMES WHITCOMB RILEY, In St. Nicholas. veling! them, ISPTIIPLY o )i Wy — { TRYING IT ON THE CAT. [Photographed from life for “‘The Call” by Theodore Scherwin.] MEMENTOS OF THE LOST CAUSE. Swords and Other Confederate Relics at Atlanta. There is a small hall just beyond the Massachusetts building at the Cotton States and International Exposition which contains exclusively mementos of Confed- | erate days and the *‘lost cause.” Of course, old battle flags figure exten- sively and are the cbject of much in- | An immense blue | g3 o days. terest and sentiment. flag is the one which floated over Fort Moultrie during the bombardment of Fort Sumter. Another is of silk, and was made by the ladies of Richmoud, Va., from their evening dresses and presented to General Kirby-Smith. It figured at Bull Run. An old Georgia veteran is worn and dilapi- dated, stained and scarred from having done duty in twenty-three batiles. On the wall, just opposite the door, so that they greet each wvisitor as he enters, are two flags held by a shield, npon which, in golden letters, are the words: Fame's trophy. sanctified by tears, Plated forever at her portal, Folded? True. What then? Four short years made it immortal. There are manl}; swords, among them being, those of Robert' E. Les, General Pelham and Stonewall Jackson, and por- traits also of these famous men. A very bhandsome sword exhibited was captured from a Federal officer, and a United States teut was vicked up at the battie of Seven Pines. The signal cannon of the Rowena is shown, which vessel was captured by the Confederate privateers in 1862 and taken to Charleston, There are several | | old guns and pistols which were used in the Revolutionary and Mexican wars, as well as the late war, and a heavy iron pike is one of the Jot made by the order of Joseph E. Brown, Governor of Georgia, to arm the militia with when firearms were scarce, and there is also one of the signal corps glasses, made in London, for the use of the Southern army. Northern visitors often ask for some of the evidences of the wealth and luxury | | that the South was noted for before the | war, but such relics do not belong to Con- Then even the daintiest and most delicate of Southern women de- prived themselves of every comfort that they might send clothing and other ne- cessities to the fathers, brothers, hus- bands and sons, the latter often mere chil- dren of 14. The silk dresses of the rich were used to line coats and blankets, that they might be the warmer for it, and as time went on it became a difficult matter to buy even a dress of ordinary print for love or* money, especially Confederate greenbacks, so homespun dresses were verg generally worn. A sample of one of these is shown which served as the wed- ding dress of a young lady of John C. Cal- houn’s family, with leather buttons, also home-mad>. Bonnets and hats were con- trived of all sorts of materiais, and ina case there is one especially hideous affair of black satin and bombazine, which in those days was considered a ‘“love of a bonnet.”” In another case is a pair of white satin wedding slippers, which in some way were also made by feminine fingers. A daguerrotype of a sweet-taced girl is there, and the story connected with it makes one interested in the original, | of these was us During the war 2 soldier left this picture with a lady, asking her to keep it for him till he returned for it, but as he never came it was supposed that he fell on some battlefield, and now the daguerrotype is placed in a conspicuous place, 1n the ho that some one may recognize and claim it. There are many army blankets, and one by General Cheatham in both the Mexican and Civil War; there is the saddle from which General Paul Sem- mes fell when mortally wounded at the battle of Gettysburg; there is a bracelet made from the buttons of General Beau- regard’s uniform; there are the field- glasses and knapsack carried by General Gordon, and buttons and epaulets which adorned the uniform of Stonewali Jack- son. Then there is a Confederate quilt, each square made of pieces of Confederate flags, parts of Jefferson’s hat iining or bits of ribbon with the names of Southern heroes embroidered upon them. There is one article, however, which causes the tears to spring to the eyes of all who view it, and that is an open satchel of an officer who was killed, containing ar- ticles just as they were sent home to the dead ‘soldier's wife. There is a Bible, a meerschaum pipe, a silver fork and silken underwear, which tell of the refinement and accustomed luxury of him who died on the battlefield, and in one corner is the last letter received from his young wife. His widow is a dear old lady now, with hair as white as snow, and the younger generation never tireof hearing her remi- niscences of the war, and how her hus- band’s friends escured with his body in the night through the lines of the enemy. A blanket is exhibited which she made for Lim with her own fingers, and lined with the silk of one of her dresses, and also a warm zouave cap made from her wrapper. Visitors from every section seem tolose all urkind feelings when viewing these si- lent witnesses of sorrow and suffering and unsung deeds of bravery and nobleness. Miss Kirby-Smith noticed a lady drying the tears which came when looking over the old patched uniforms, and asked herif she had lost any one in the Southernarmy. But no, the lady was from far-off Colo- rado, but she said that her husband had louzf\t in the Northern army, and was killed in the battle of Gettysburg, and her heart went out to the gray as well as the blue, for she knew how both sides suf- fered.—Atlanta Letter to Boston Tran- script. e MEN OF THE WILDERNESS. National Greatness Largely Generated on the Frontiers of the West. The keen public interest in the “Ren- ard” discussion is to be ascribed to the profound importance of the question thus brought under consideration. For ages mankind has been asking this question, What are the elements of success, what are the shoals and rocks -of disaster? The hosts of ages have taken that problem into their inner consciousness, and it will re- main forever the chief problem of man- kind. In this discussion much has been brought out that is thoughtful and wise; but in some instances errors have been ad- vanced and a_sickly sentimentalism given expression. One writer considered it mat- ter for regret “that lofty and cultured minds have drifted to the rough West to work out a future.” With that sentiment this paper has no patience. American history is illuminated by the lofty and noble lives of men of the West and children of the wiiderness. Washing- ton was a product of the woods and fields and began his career of usefulness by sur- veying the wilderness. Franklin was first set at work in his father's chandler-shop cutting wicks and filling moldsin the man- ufacture of candles. At the age of 13 Hamilton was put to work in a countin, office. John Jay was born in New Yorg when New York was a frontier, and prac- ticed law in the metropolis when it had less population than Spokane now has, and much less of civilization and refine- ment. Jefferson’s father was a Virginia lanter, and Jefferson was a hunter, a dar- ing rider and swimmer in the wilds, and of a decidedly rustic bearing in his early manbood. Jackson was born in a cabin, and was essentially a product of the backwoods and the frontier. Webster was born on a farm and worked at common farm labor. Clay was the *‘millboy of the slashes” in the pioneer days of Virginia, and at 14 was set at work in a country store. Lincoln was a child of the backwoods, slept on a bed of cornhusks, read by the fitful fire of the open hearth, toiled at the laborious work of clearing a forest farm, bent his long arm at the sweeps of the flatboat, and sold goods from behind the counter of a little store. - Grant was a farmer boy of the West, a tanner and a teamster. Garfield was a backwoods product, and his first pro- ductive labor wasas a canal-boy. Sheri- dan was schooled in war on the Texas and Oregon border, The Shermanscame out of Ohio in its pioneer days. and the Har- risons were products of the ‘“rough West.” Turning from statesmanship and war to the more quiet paths of literature it is learned that Cooper was reared in the wilderness of Central New York. In the language of his biographer, “‘the wilder- ness was his earliest and most potent teacher.” Irving’s father was a small merchant in New York. Hawthorne's father was captain of a trading vessel, and a part of his bovhood was spent in the wilderness of Maine. Of these surround- ings he has written that ‘‘nine-tenths of the adjacent country were the primeval woods."”’ Longfellow was reared in provincial Portland, Me., and his biographer has written that “it possessed no deep wells of experience or culture; it was compara- tively a new place mm a new country.” ‘Whittier was a farmer’s boy and learned shoemaking. The list could be continued indefinitely. If aught is conclusive .in American his- tory, it is the lesson that the National greatness and glory have come up from the common walks of life, and thata great part of it, much the greater part when population is considered, has been gen- | erated in the wilderness or within sight of the border. Minds poisoned with the delusion that they are too noble and lofty for associa- ciation with Western character are not wanted anywhere. They are the froth of civilization.—Spokane Spokesman-Review. ————— Mary, Queen of Scots, was tall and slender, but very graceful in all her actions. Her face does not seem to have been especially beautiful, for she had T rather irregular features; but her fascina. tion of manner was irresistible. She had a way of cocking her head a little to one side and of looking sideways at the person’ with whom she was talking that gave a strong impression of coquetry. NEW TO-DAY. BIG SHOE FACTORY, and save 50 cents to $2 per Eair. ROSENTHAL, FEDER & (0, 581-583 MARKET ST., Near Second. Open Evenings “