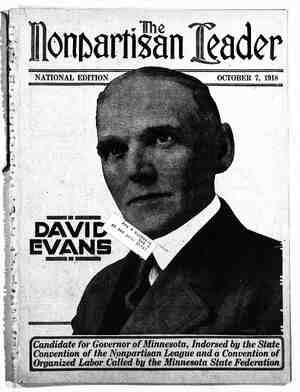

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, October 7, 1918, Page 5

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

&Y : ‘country. ~ "ers’ association. His firm' was Chamber of Commerce Hit by Senatorsd Special Interest Body, Which Attacked Federal Trade Commission and Which Is Investigating the League, Gets Bad Drubbing Before Agricultural Committee Washington Bureau, Nonpartisan Leader INVESTIGATION into the real character of the Chamber of Commerce of the United States has been started. The senate committee on agricul- ture is the tribunal before which the testimony is being taken. It is possible that the senate itself may decide, by resolution later on, to remove some of the camou- flage from the imposing front of the chamber, and let the country know the amazing facts. Here are some of the points of the testimony drawn unwillingly from theq first two representa- tives of the chamber who were summoned: 1. A letter asking for contributions of $1,000 each was sent out, in 1915, over the signature of Walker Allen, now New York agent of the Cham- ber of Commerce of the United States. In this letter Allen urged that the principal capitalists in America should join in putting upon its financial feet a body which would safeguard the common interests of business. 2. That letter went to a picked list of 100 men, : and among those who responded with $1,000 pay- ments into the chamber’s fund were several of the big meat packers, the corpora- tions in which they were di- rectors. and business magnates who_incidentaily held stock in the packing companies. The so-called packing group fur- nished a large proportion of the money which launched the chamber as a power in the NO EVIDENCE AGAINST COMMISSION 3. Rush C. Butler, a Chicago corporation lawyer, was chair- man of the federal trade com- mittee of the chamber at that time. He had been one of the legal counsel of ‘the Cudahy Packing company from 1910 to 1915. He was counsel for the Michigan Paper Manufactur- counsel for the National Feed Manufacturers’ association. He had formerly been active in promoting the creation of the United States commerce court, and took part'in many confer- ences looking toward making the federal trade commission an agency for the promotion of large business interests. 4. Butler wrote the “re- - port,” made public recently by the Chamber of Commerce of the United States, denouncmg the federal trade commission for its attitude toward the meat_packers, the paper manufacturers and other big ‘business groups. He ‘admits that he has no s evidence, ‘and the chamber has no-evidence, suf- ficient to justify a denial that the charges made by the federal trade- commlselon agamst the pack- ers gre true. 5. The International Paper cdmpany gave $1 000 to the fund of the chamber of commerce, although Butler denies that he knew of that connection when he took the side of the paper manufacturers in his report. The only business interests thus far-de- fended against the federal trade commission by "the chamber have been those»whlch contrlbuted to the ‘support of the ¢hamber. 6. Butler; and the officers of the chamber, are 'net merely hostile to the federal trade commission; “ they demand that the commission cease to: inter- fere with the blg business interests by - drastic methods of inquiry and discipline, or that congress g - shall “abolish- the commission’s powers, . PROGRESSIVE"SENATORS EXPOSE ‘COMMERCE MEN Butler Justlfies the packers in spendmg mil- _hons ‘of dollars'in pretended advertising in all the - newapdpei'd'bt the Umted States because the fed- facbory for the big interests. mission to bulldoze the president. eral trade commission gave to the press a state- ment that it had charged two of the big packers with furnishing bad meat and unfit chickens to soldiers at one of the army camps. ; Senators Kenyon of Iowa, Norris of Nebraska and Gore of Oklahoma did most of the questioning of Allen and Butler. Allen explained that he wanted the big business magnates to realize, when he sent out his begging letter, that the chamber was - “their pie.” Kenyon asked what he meant by “pxe ” Allen smilingly agsured-him that he meant’ that the chamber was to look after the general, patri- otic, common interests of the business community. It was not to safeguard any particular individual or any one interest. Then Kenyon went over the list of 100 million- aires and big concerns who were honored by the request to “come through,” and disclosed the cu- rious coincidence of their relation to the packers. There was the National City bank, the Eastman Kodak concern, the American International cor- poration and a long list of others—each one con- nected with the packers through stock ownership one way or another. The chamber seemed to be a packers’ family affair, so far as the sinews of war were concerned. Kenyon thought that was 'a fortunate thing for the packers—they gave money = THE WHITE HOUSE AT NIGHT et Within a stone’s throw of the president’s home is the magmficent office - bulldmg of the United States Chamber of Commerce, which, in the words of one of its leaders, is the ‘“pie” to the Umted States. Chamber of Commerce at a time when congress was discussing an inquiry into the packers’ methods; behold, when the govern- ment publishes a report on the packers “which arousgs the whole nation, the Chamber of Com- _ merce. of the United States arises and violently denounces the arm of the government whlch has disclosed the packers’ crimes. Butler told the committee that he had_ criticized -the federal trade commission in two other cases before the packers’ affair came up. ‘The first was the protest he made when the commission attempt- ed to settle the quarrel between the print paper manufacturers and the consumers of print paper. The second was the instance in which the brass bed manufacturers tried to form a combination to shut out further competition. In that case the commis- ~gion tried to have the department of justice prose- cute them for restr'aint of trade, when they had gone to the commission with an appeal for help in their scheme.. He seemed to consider that the ; federal trade commission had “tipped off” the prose- cuting ‘authorities when it ought to have advised the brass bed manufdcturers on how to get around the ‘anti-trust law. )8 the packers wrongs Butler was: eloquent " PAGE FIVE ‘. It recently threw one of these pies at the federal trade com- Another has been hurled at the Nonpartlsan league. Read on thls page the story of the senate exposure of the pie men. _He wanted to know what right the commission had to publish its conclusions and charges without pub- lishing the evidence on which the charges were based. Norris reminded him that it was the presi- dent who had seen fit to publish these conclusions and charges ahead of the volumes of evidence. Butler hastily denied that he meant to reflect upon any act of the president, as he-was “for him.” LAWYER FAILS TO FIND COVER Then he had a brilliant idea. He read a press statement. issued by the federal trade commission last May, announcing that it had charged Wilson & Co. and Morris & Co. with selling bad meat and chickens to Camp Travis, Texas. Butler denied, in indignant tones, that any bad meat had been furnished. He admitted that he had no proof of his own claim. Still, he objected to the commis- sion’® publishing the accusation before it had proved the packers’ guilt. “Do you know to what extent the packers have been advertising in the newspapers throughout the country ?” inquired Norris. “Do you know that they have for some time been paying for large amounts of advertising space in almost every news- paper in the United States, and don’t you think it possible that this intensive advertising campaign © —in which, by the way, the packers do not seem to adver- tise any of their products— might tend to influence the press?” “That would imply a de- graded press,” answered the chamber spokesman, shortly. “Then, how do you explain the expenditure of so much money in advertising in the newspapers ?” Norris insisted. Butler then told the sad story: of the bad meat charge and said that “if the federal trade commission had conduct- ed its business in the manner of a court it would have been unnecessary for the packers to spend that money on adver- tlsmg Norris agreed, but asked whether Butler would_ have escaped jail for contempt if he had gone before the supreme court and denounced it as he had denounced the federal trade commission. Butler de- cided that he didn’t want the commission to act like a court. ed, “did the packers not dis- “cuss that bad meat charge in their advertising, if they were trying to get the public to again have faith in them?” “I commend their judgment,” said Butler, “in not. perpetuat- ing that kind of publicity. I _think that the action of the commission in this in- stance does them so much wrong that the expendi- ture of $25,000,000 in a single year, in any way they saw fit, would not be sufficient to repair the damage.” Norrls was still curioiis to know why the packers ~ did not advertise their side of the story of those bad meat charges. Butler groped in his brain for an answer and finally got it. “I-have been ver§ much impressed with one of ‘the Swift' advertisements,” he said. It shows the face of a handsome, dependable man, and.it states that this is the manager of one of ‘their branch houses. Now, that kind of advertrsmg impresses me deeply, and I believe it impresses the public with faith in the packing. industry.” The committee smiled. Presently E. C. Lassater of Texas, a big cattle raiser, was on the stand. He testified that the packers’ “Then why,” Norris persist-" wholesale = distribution of advertising ° ‘money among the newspapers was begun a :year i before the federal trade commission made’ its e charge that bad meat had been sold by the pack- 2 .ers to the soldiers. Foanl Chairman Gore said that the commlttee wouId f call other witneeses : s