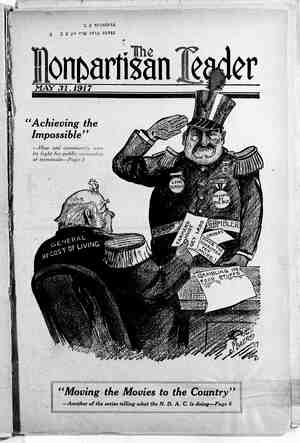

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, May 31, 1917, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Public warehouse and wharf at Los Angeles, part of the $10,009,000 public terminal system. fight the proposition of the breakwater at San Pedro, where Los Angeies wanted it. The usual political wire- pulling and bulldozing was resorted to by the railroad. But the people of Los Angeles put up a united front. The railroad lost and the government’s $3,000,000 breakwater was bui]t at San Pedro. It is a wall of masonry two miles long stretching out into the sea. If the water was drained off, it would appear as a wall 200 feet thick at the base, 20 feet thick at the top, from 62 to 66 feet high and two miles long. It effectively breaks the swell of the ocean and carves a harbor out of the sea. Behind it the development of the Los Angeles port has taken place. LAUGH AT THE EFFORT TO REACH SEABOARD But Los Angeles was still twenty miles from this manufactured harbor. It had won, however, the first round of the fight, and proceeded to the second. The city, still an inland community, formed a “harbor” commission. Neigh- boring cities laughed, and the private interests controlling every foot of the eight miles of shore behind the San Pedro breakwater were amused. An inland city with a harbor commission! It was humorous. But Los Angeles proceeded to ex- tend its city limits to the sea, across the twenty miles of intervening terri- tory. All the country smiled when the city annexed a strip of land a half mile wide and twenty miles long, ex- tending from the old Los Angeles city limits to the city limits of Wilmington, a municipality that adjoined the munic- ipality of San Pedro. “Shoestring” addition, it was dubbed. It was good “feature stuff” for newspapers all over the land. It was a long tentacle ex- tended by the city to put it in touch with Wilmington and San Pedro, so those communities, bordering on the ocean shore, could also be annexed, making Los Angeles a coast city in fact and in a position to develop pub- licly owned terminals. The annexation of the “shoestring” was a good joke, of course. It was put through in spite of ridicule and in spite of the opposition of selfish in- terests that knew in their hearts that the city was in earnest. Los Angeles then proceeded te the next step, the annexation of Wilming- ton and San Pedro, the municipalities on the shore behind the government breakwater. It was comparatively easy to overcome the opposition to the annexation of the “shoestring,” but it was a bitter three-year fight to annex the coast towns, which had a combined population of about 20,000. San Pedro and Wilmington could not be annexed without their own consent, and in addition the laws of the state had to be changed to give the authority. It was easy for the private interests opposed to public ownership to work up a formidable opposition ainong the citizens of San Pedro and Wilmington against annexation to Los Angeles. Local pride and prejudice were appealed to to discredit the annexation plan among the citizens of the coast towns. They were told that their independence -was tQ be sacrificed to Los Angeles’ ambition; that they were to be gohbled _up, so to speak, by the larger city. But despite all this the two towns voted to become part of Los Angeles. Los Angeles promised .them that if they did vote for annexation, the city would spend $10,000,000 in ten years on publicly owned wharves, warehouses and other terminal facilities, to make the new Port Los Angeles the equal of any on the coast. CALIFORNIA LEGISLATURE BLOCKS THE PEOPLE The legislature of California, domi- nated by corporate influence, refused to pass the laws needed to permit the annexation of the coast-towns. The Southern Pacific Tpolitical machine, then notorious all over the United States, had things its own way. These were dark days for the proposed pub- licly owned terminals. The city had to wait two years for the next legisla- ture. Another desperate battle was fought at the state capital with the corporate interests, but this time the' city won. The necessary authority for the annexation of San Pedro and ‘Wilmington was given. Then the mat- quit now. It tied the bond issue up in the courts with two years of litigation. But the courts finally declared the bonds valid and they were sold, per- mitting the work on public terminals to start. Two years later the people again expressed their faith in public terminals and the harbor projects by voting an additional $2,500,000 in bonds, and the city is pledged, in its compact with San Pedro and Wilming- ton, to vote $4,500,000 more for further development during the next few years. THE COURTS ARE ALSO CALLED IN It would make an endless story to. go into all the details of the fight that has never let up against the publicly owned harbor plans. The railroad and other interests have not quit yet, though they are badly beaten. The city Publicly owned wharf at Los Angeles harbor, another part of the system which the people fought ten years to get. ter was fought through the courts, on injunction suits brought by property owners hired by the private interests to fight the plan. Again the city won. At last Los Angeles was a seaport, al- though as yet it had no harbor facili- ties. ~ To build the public terminals the people of greater Los Angeles in 1910 voted $3,000,000. The election was car- ried in the face of the bitterest oppo- sition of the private interests controll- ing the water front and the strong party in the city that opposed munic- ipal ownership of any kind. After the election was carried for the bonds the opposition did not quit. It did not quit when Los Angeles won the break- water fight, nor when the “shoestring” was annexed, nor when Wilmington and San Pedro came in—and it did not Part of the market facilities built by Los Angeles for the fishi market was built wi_th bond had to fight a long suit through the state railroad commission and courts to get justice in the matter of freight rates between Los Angeles proper and the harbor, a twenty-mile haul. The final findings reduced rates so that The people of Los Angeles faced every obstacle that could be imagined in their fight for public ownership, the greed of private interests, a railroad controlled legislature, years of litigation in the state courts. The determination of the people to own their own terminal facilities carried them through every fight victoriously. What Los Angeleshas done, the people of the Northwest can do. shippers are now saving half a million " dollars a year on this twenty-mile haul. When the city’s engineers began to look over the ground for places to build the publicly owned facilities for ship- ping they found access to every foot of the navigable channels in the har- bor at San Pedro and Wilmington cut off by railroads and other private in- terests that had gobbled up the water front. I recounted in the article on the state-owned harbor terminals at San Francisco how the state constitution of California has always prohibited the selling or giving away of water FOUR ny industry and operated under public control. money voted by the people. front on the state’s harbors, and I told how Oakland had to fight the railroads and other-interests for years in the courts to get back what negligent and corrupt public officials had sold to private interests in defiance of the con= stitution. = The same thing had happened at Los Angeles harbor. Los Angeles, through the attorney general of California, brought suits in the name of the peo- ple to recover this land wrongfully in the hands of the private interests that bottled up the harbor. The litigation ended as it did at Oakland in the courts restoring the harbor lands to the people. A few tracts -on Los Angeles harbor they left under control of, private interests, but the bulk was restored to the people. Over that which was not restored outright the courts gave the city public right of way for “purposes of navigation and fisheries,” which amounts to public control of even the few tracts left in private hands. PEOPLE GENEROUS WITH CITY OWNED UTILITIES When completed the Los -Angeles publicly owned terminals back of the breakwater at San Pedro will be sec- ond to none on the Pacific coast. Great concrete and steel wharves with the latest equipment for handling freight and passenger traffic have been built - and more are under construction. Large concrete warehouses .of the most modern type have been built and others are planned, all for public use at nominal storage rates. Besides the $5,500,000 in bond money the city has spent on these utilities and in dredg- ing the harbor channels, the govern- ment spent $3,000,000 on the break- water and $2,000,000 in dredging in the harbor. So the publicly owned harbor and utilities have cost to date over $10,000,000. The harbor is just be- ginning to be self-sustaining—that is, its revenues, without the aid of any money from taxes, will soon be.able to take care of all the interest charges, retirement of the bonds/as they mature and all operating expenses. It would have been seif-sustaining before this had not the European war of the last three years paralyzed shipping every- where. Considering conditions and the size of the project, it has already made a remarkable financial showing. The city has built, also, a publicly owned line of railload to connect up the various harbor facilities, so that the railroads can not unjustly ‘discrimie hate in switching charges. It is a re- markable fact that every publicly owned terminal project I have investie gated has found it necessary to put in a line of publicly owned railroad con- necting the various units. In every case the railroads have made this nece essary by their gross discrimination against the public wharves and ware- houses. Seattle has not built its pub- lic railroad around the harbor yet, but the port commission there realizes it has to be done, as the present discrimi- nation against the publicly owned terminal utilities is preventing their proper development and usefulness. The people of Los Angeles had ob= stacles to overcome in building a har- bor and public terminals that would have discouraged a city that had less faith in public ownership or was not inclined to throw its whole resources in the fight to win. I said at the start that public ownership had accomplish=- ed the seemingly impossible at Los Angeles. I don’t think anybody can look at the facts and come to any other conclusion. / This fish - i\