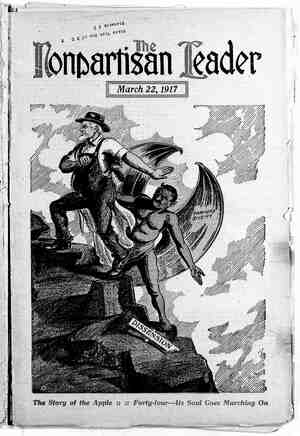

The Nonpartisan Leader Newspaper, March 22, 1917, Page 5

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Some Pacific Northwest apples on display at the annual National Apple show at Spokane. Louis W. five prize boxes under the sign on the extreme left, in striking contrast to the average price of 40 cents a bo popularize the Pacific Northwest apple and advertise it, helping to create new markets, in fruit land of a few years ago. HE Pacific Northwest 10 years ago got the idea that five acres of orchard land would sustain a family and that 10 acres« would make a fruit grower rich. It was an intoxicating idea. Visions of a land teeming with population and riches fired the imagi- nation. Then the Pacific Northwest imbibed freely of real estate boom and speculation in fruit land. It was a grand spree. The Pacific Northwest is sober now. The effects of the spree, however, have not worn off. The fruit country has been through disaster after disaster, and the industry is now facing its most serious problem. The apple has long been associated with temptation’ and disaster, and Idaho, Washington and Oregon have added several interesting chapters to the story. The mild climate and rich soil of this region produce a wonder- ful fruit—big, juicy, sweet and beau- tiful in color. The orchardists of 10 Years ago dressed apples up in neat, evenly packed boxes, after sorting them for size and color, and put fancy labels on them. They made a novelty to tempt the world. They did . tempt. They brought big profits to the first fruit growers who abolished the custo- mary eastern method of putting apples in barrels without regard to size and color, and often without regard to variety. FAME OF NORTHWEST APPLES TEMPTED LAND EXPLOITERS The Pacific Northwest apple leaped into fame. It tempted somebody be- sides the consumers, who paid a little more for this beautiful, blushing fruit, all of a size and color, yet distinctively individual. It tempted the land boom- ers and real estate sharks. All the available fruit land— and a lot that was called fruit land but wasn't—was platted into five and 10-acre plots for the eager multitude that was to swarm onto the land led on by the brass bands of the commercial clubs, the subtle publicity of the railroads and the stories of fabulous profits told by real estate men. “A family on every five acres!” This became the slogan. Never was land more effectively boosted. Everybody in the three states, it seemed, invested in fruit land, or what passed for fruit land during this spree. Thousands of easterners who saw the brilliantly painted rainbow on the western hori- zon sought the pot of gold beneath it. “Back to the land!” Not slopping hogs or milking cows or grubbing in the soil or any of the other drudgery associated with farm life—ah, no! They came to be gentlemen orchard- ists, to set out even rows of trees that would blossom in a profusion of pink and reds in the spring and drop beau- tiful, plump apples in their arms in the fall—apples that an eager world would pay fancy prices for. Real estate companies did not stop at prices that would buy orange -orchards in California. They set out young or- chards so that the embryo orchardist could settle right down and begin to rake in the profits in a year or two when the trees began to bear. These were orchards to sell, not to grow apples. They were planted on land to sell, not land fit for orchards, in many cases. It is no wonder that hundreds of these made-to-order fruit farms have been abandoned, while others have impoverished owners and flat- tened out rosy dreams. i APPLE OUTPUT SWOLLEN BEYOND MARKET CAPACITY The natural result of all this, of course, was a production of apples that increased by leaps and bounds annu- ally, growing out of all proportion to the markets that could be found or created. The incomparable apple of the Pacific Northwest became a drug on the market. Growers were lucky to get a meager living and thousands went broke and quit. While conditions are now readjusting ‘themselves some- what, this is still the problem of the fruit country. You will not get this story in just this way_ if you talk to the commercial clubs in the Pacific Northwest. You will not get it if you search the files of the newspapers. But there are men in the fruit country who know the condi- tions and are trying to solve the fruit problem and who will tell the truth. ‘W. S. Thornber, director of the exten- sion department of the Washington state college at Pullman, Wash., is one such. He says: “Seventy-five percent of the growers are dissatisfied because they made no money during the last three years. Ninety-five per cent of the growers would gladly sell their holdings now for considerably less than they paid for them and willingly lose their time and interest in the bargain. Sixty-five per cent of the orchard area during the past two years has been so seriously neglected that it is a question in my mind now whether or not it can ever be brought back to profitable fruit production again.” REASONS FOR COLLAPSE OF ORCHARD BUSINESS Mr. Thornber sums up the reason for the condition existing. He gives five main causes, as’follows: ‘ ° “Unreasonable boosting of orchard lands. “Misrepresentation of the possible returns of orchard lands. “The keen American desire to make a change. : . “The inborn desire to speculate. “The cutting up of orchard proper- ties into such small units that it is almost impossible for the average family to make a living upon the given area.” The story of the fight of the orchard- ists during the last few years to save their investments and make a living is a story of feverish efforts by com- mercial clubs, newspapers, bankers and others to right the conditions and solve the problems that their own participation in the boom of a few years ago brought about. It is also a story of the fight of the producers against the fruit middlemen and mar- ket pirates. Last but not least it is a story of the breaking down and failure of the co-operative movement among growers, at least so far as a compre- hensive, general plan of marketing is concerned. For several years prior to 1912 fruit growers in general averaged little bet- ter than expenses, but 1912 was the first big general disaster. It is hard to flgure the cost of producing a box of apples and various figures are given. Private fruit marketing concerns, tak- ing profits and commissions for mar- ‘keting fruit for growers, tell you that it costs 65 cents a box and that if a grower gets that he breaks even. An examination of the farms of the ‘Wenatchee valley in Washington by government experts put the average cost for that valley at 77 cents. O. M. Morris of Washington State college in an address at the 1916 National Apple show at Spokane mentioned 95 cents to $1.18 as the cost of growing a box of apples. Take even the lowest estimates as the cost and you find that in 1912 the great bulk of the crop sold at less than the cost of production. That had happened before in various districts.. ‘But this year there was a - big crop in all districts and all districts suffered alike. APPLE FAILURE A BLOW TO ENTIRE NORTHWEST The bottom fell out of the market entirely and it not only ruined thous- ands of growers and put other thous- ands deeper in debt—it was ‘a severe Here’s our old friend the bureau of markets of the U. 8. department of agriculture—helping the commission men to get around the law. If the farmers are to be helped they must help themselves. FIVE Hill of the Great Northern railroad gave $200 for the) X growers got in 1914, The Apple show is a device to so badly needed on account of the great over-production due to the boom financial blow to all business and in- dustry in the Pacific Northwest. The producer is at -the bottom of the economic edifice and the great complex structure of middlemen, of banking and business, is built on that foundation. If the foundation fails, the structure falls. Thus it was in the fruit country in 1912. The commercial, banking and business interests realize this and that accounts for the efforts of these inter- ests from 1912 on to solve the market- ing problem for the growers—to solve it as they thought it ought to be solved, with little or no consideration, except perfunctory, for the growers them- selves. Prior to 1912 growers in various dis- tricts had perfected co-operative fruit marketing companies and had handled the bulk of the fruit crop in various districts with more or less success, generally getting as much for the prg= ducer for his product as private mar- keting firms, commission men and fruit speculators had been getting for the farmer. The Yakima Valley (Wash.) Fruit Growers association, or- ganized in 1910," and similar organiza- tions in the Hood River (Ore.) district and in Idaho and elsewhere were exam- ples of more or less successful growers’ co-operative companies. But they operated independently and competed with each other and with the private fruit marketing agencies, some of which were powerful. APPLE GROWERS TRY CO-OPERATIVE MARKETING After the disaster of 1912 the neces- sity of a general marketing agency for all districts was seen. A central agency to handle the en- tire crop of all these various district co-operative concerns was considered the solution, and with the help of the business interests the various growers’ companies in Idaho, Oregon, Washing- ton and western Montana organized the North Pacific Fruit Distributors, a strictly co-operative central marketing agency through which all the co-opera- tive companies of the various districts could market their crops at cost, dominating and controlling the market and keeping prices up above the dead line of the cost of production. The Distributors were organized in time to handle the 1913 ¢rop. This was a short crop, a reaction from the over-produc- tion of the prior year, and the Dis- tributors handled 40 per cent of the tonnage with considerable success. This great co-operative plan was hailed with delight everywhere and by all in- terests throughout the fruit districts, except by the private fruit marketing companies, which of course resented a farmers’ organization marketing the fruit at cost and taking away the com- missions of the brokers and the profits of the speculators. Then came 1914 the second big dis- aster for the fruit industry—much worse than the disaster of 1912. The big war was responsible, probably. The P B P