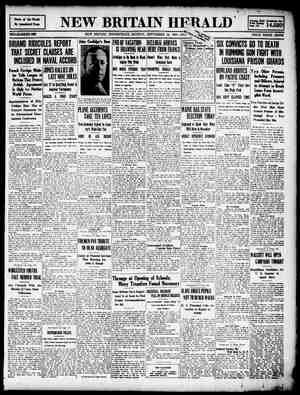

New Britain Herald Newspaper, September 10, 1928, Page 13

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

NEW BRITAIN DAILY HERALD, MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 10, 1928 ND @ ELEANOR EARLY HIRLW, COPYRIGHT 1928 & NEA SERVICE INC. - . “They have sown the wind, and they shall reap the whirlwind."—Hosea VIII, 7. CHAPTER 1 N Sybil Thorne was younger, and her picture ap- every day or two in the social columns, it was usually captiohed “Boston’s Fairest Bud.” Society editors heaped praise and compliments upon her, One of them declared her to be “the most popular and the most beautiful” debutante of the season. Another pronounced her the best dancer, and a third the most ac- complished sportswoman. A short while ago one of the newspapers, launching a contest to elect “Miss Boston,” rescued an old cut from the reference room, and headed it “Madcap Belle—Is She Boston's Prettiest Girl?” But Sybil isn't exactly a girl any more. She was 80 last month, Her first triumphs date back to the war. It was then she grew up; falling in love, after the fashion of adoles- cents, with a soldier. Shortly afterward she parked her corsets at a tea dance and proceeded to the enjoyment of those reckless pursuits which reformers and professors write about with great f¢ 3 The “youth of the land” was becoming subject for tirade and tears. Worthy citizens formed vigilance com- mittees and wrote articles. Some of them have been sup- porfing themselves that way ever since. Sybil was 18 when she first got herself talked about. It was ly because she was so unusualy pretty, People can believe almost anything of a girl with beautiful legs, particularly if she possesses, also, a certain symmetry of form and loveliness of feature. éyhil’l eyes are beautiful pools of velvety softness, flecked Wwith little darts of cop- pery stuff. Her skin has an ivory pallor, and she makes ;gp her lips so they look like a bleeding gash in her pale ace. 'ROM the time Sybil could talk, she has been a creature of moods and tempers. Her temperament probably has had a good deal to do with fashioning her life, But "l‘e{;l'.o’ course, there was the war, The war bungled a lot of things, ; Sybil just missed being & war bride. At Miss Middle- ton's select boarding school all through the winter of 1917 she folded Red Cross bandages and made innumerable bags of cretonne with draw strings. In each bag she put a knit face cloth of uncertain dimensions, a package of cigarettes, a bar of sweet chocolate, a pair of socks and a sleeveless sweater. During vacation she rebelled. “It's so SIMPLE!” she fumed. “Crazy old sweaters and socks that don’t match! Afghans and wash rags!” She threw her knitting needles away, and Miss Mid- dleton put her down as a Bolshevist, “I'm a conscientious objector,” Sybil used to say; and that, in those days, was regarded as a great heresy. One night at dinner she threw a verbal bombshell into the fam- ily gathering, . “I'm sick to death,” she told her astonished parents, “of the futility of the life I lead. I want to DO something. I'm going across.” Her father choked on his rice pudding—“Nothing of the sort,” he objected, when he caught his breath. “Are you erazy, Sybil 7" Her mother was quite unmoved. “Don’t you think, dear,” she questioned mildly, “that :\éopr’ poor father and I have enough to worry about as itis?" “ : Mrs. Thorne's eves were blue and faded. She knit from morning until night and denied herself all luxuries. Tad, the child of her heart, was at Tour with Battery A of the 101st, and there were terrible tiding those days of slaughtering in Seicheprey and the Somme. ° Mrs. Thorne had two records that she played over and over on the phonograph: “There’s a Long, Long Trail A'Winding, Into the Land of My Dreams,” and “Over There.” She thought Tad probably sang them in France, and it made her feel nearer to him. As she wound the machine and adjusted the needle, the same thought was always in her mind—“Perhaps this very minute Tad is listening to these same words.” The thought saddened and comforted her immeasurably, after " the strange fashion of women in anguish. She.- regarded Sybil mournfully, . “Come to Mrs. Ward’s with me tonight, dear,” she invited, “There’s a new way of making bandages—not cutting at all—just pulling threads. A woman from the Metropolitan Chapter is coming out to show us.” Sybil declined with scant grace. “I'm sick of Red Cross soirees,” she said. Tears flooded her mother’s eyes. . “I really think,” she began tremulously—“I really think Sybil, you ought to have a little more consideration —with Tad over there—and everything.” She stumbled from the room and the next moment they heard her at the phonograph—“Over There—Over There—" Sybil put her fingers in her ears. “Oh, hord—" she muttered. “You must remember,” her father told her sternly, “that your mother’s nerves are all on edge. Don’t let me hear any more of this talk about going across. It's non- sense—utter nonsense!” HE never knew that the next day Sybil went to Y. M. . C. A. headquarters and volunteered for overseas service, for presently there was a ruling that no relative of soldiers would be accepted, and Sybil resigned herself to the inevitable. § “I tried,” she told herself savagely. “God knows I ?:n't want to play with gauze while Tad and the rest of em—" She choked on the very thought. Often at night she saw Tad lying in a pool of blood. His face was blown away sometimes. Or there was a great hole in his chest. And, if he wasn't quite dead, he was gasping—trying to say something. She and Tad were such pals. It was hard on a girl to cut bandages back in 1918 and do nothing more valiant than knit like an old woman. Particularly if a girl and her brother at the front meant as much to each other as Tad and Sybil Thorne. Then something happened that made it even harder. Suddenly, inexplicably, Sybil fell in love. She went one day to Devens with her mother to take a box to a boy in Mr. Thorne’s employ. The boy was a buck privatesin infantry. Shyly he introduced them to his buddies. One of them was a tall, slim youth, with chestnut hair, bleached like gold from the sun that shone on Devens, and blue eyes with black lashes. They had taken his books from him and given him a gun with which to kill other boys full of promise, and a trench knife, in case he met a youth in hand-to-hand encounter and could not use his gun. At the moment Sybil experienced only one reaction to the blond beauty of him. He thrilled her. John Lawrence was his name. And it was plain that he was a private through accident only. Obviously he had antecedents. Family, traditions, breeding—all that sort of thing. He ed easily. Presently it developed that he had been at Yale—a second year man. He belonged to Tad’s fraternity. Mrs. Thorne became interested. Per- haps her husband—he knew Mr. Lawrence’s colonel—per ~——haps he could help him. Officers’ Training School, or something, John Lawrence protested. Oh, no—really. He woul make the grade all right. Expected, to tell the truth, to be chosen for the next training school. He was very grate- ful, however, Mightn't he show them around a bit? They made a tour of inspection, with young officers glancing enviously from every barracks, and Sybil the target of all admiring eyes. In a doorway Lawrence, standing aside for the wom- en to precede him through, put his hand on Sybil’s arm. There was something in the way he did it. A possessive sore of pressure, gentle and compelling. She was only 18, and it electrified her. June was worth a whole month of it in the winter-time. Ske hugged herself inwatdly with little anticipatory shiv- ers. But presently her ecstasy was skadowed by grim fore- bodings and the fears of a woman for her beloved whc is in danger. i “But I will be brave,” she vowed. “And I will make him very happy. Then, if he should ..ave to go, I will send him with a smile.” Poor Sybil, playing with dreams. That night John Lawrence’s regiment entrained for Hoboken, and sailed the next midnight. * ¥ % He left a note for her with a boy at camp. A heart- broken little note, scribbled with a stubby pencil on a sheet of Y. M. C. A. paper: “. . . Goodby, little girl, good- by. Oh, Ilove you so, my precioug wife-to-be. . . . I love you I love you. ..."” She carried it for months down the front of her dress next her heart. Girls that summer were wearing V-neck blouses cut so low that she could look down and see the folded edge peeking up from the ribbons of her little satin camisole, : Whenever she was alone she read it again and again. By Christmas, with kisses and with tears, it was worn so thin it was falling apart. Then Sybil put it in the box “Maybe therc’s no fidelity in me, Tad. I don’t know. Only Johw's got my soul, and I lon't believe lips count very much.” Before they left she had promised to write. It was a girl’s patriotic duty in those days. She promised also to send some fudge and a cake, and asked if he needed sweaters or socks. That was patriotic, too. On Sunday the Thornes motored again to Devens, ac- companied by Mr. Thorne, who handed around eigarets grandly. He took a liking to Lawrence and invited him down for dinner. The following week the young man ob- tained a 24-hour leave and spent most of it at Thorne’s place at Wianno. In the evening Sybil showed him the moon over the water and walked with him along the beach. Little waves splashed mournfully on the sands, and the moon scuttled behind a cloud. The night was fearsomely beautiful. And Sybil was fearfully lovely. She stood with her face to the sea, while the wind whipped her dress of misty stuff about her and blew her hair to John’s cheek. Then he took her in his-arms and kissed her. After that Sybil braved parental displeasure and mo- tored,to Devens every day. Her father, by permitting her to take the car, gave the affair half-hearted acquiescence. Her mother, though she admitted John “seemed like a nice young man,” frowned on the romance. Then between Sybil and her mother there grew a rift ahat was common between mothers and daughters those ays. “She’s just furious,” Sybil told her father, “because 1 dare to think about John instead of thinking of Tad every blessed minute. Her boy’s in danger—and she doesn’t care anything about MINE. I'm expected to worry about Tad all the time. But I mustn’t even THINK about John.” Sybil strangled a sob. “If John has to go, I'll DIE,” she said. “And mother wouldn’t care a bit—I know she wouldn’t. Oh, daddy, I'm so wretched!” Ineffectually her father patted her shoulder. “There, there, Sybil. Do vou love him, little girl? It's been such a short while. Mother doesn’t realize, I know. Naturally she’s frantic about Tad. Your mother is not as young as she used to be, and she’s apt to be high strung these days. Take things easy, Syb. God knows it’s hard enough to have Tad over there.” The roads about Devens and into Ayer were dusty and not conducive to romance, but beyond the camp an orchard stretched where leafy apple trees made welcome shadows. A little away from the rest stood a gnarled old tree with twisted limbs and a crotch where two could sit and love. Beneath its shade the lovers clung. “Darling, darling . . . ” When he kissed her, he felt her tears on his lips—salty, tangy—Dbittersweet. “Darling! DARLING!” He said it over and over. “How old are you Sybil?” “Eighteen,” she told him. “So young,” he whispered. “So little, and so young.” “Old enough.” Her lips against his ear were saying it. “No, no, I can’t.” He held her from him. “I might come back all shot up. I mightn’t come back at all.” “Then,” she told him bravely, “I'1 never forgive my- self if I'd let you go like this.” “Angel!” He was kissing her hair. Then she took the pins out of her psyche, and shook it down, to please him. So that he took it in his hands, anc let it slip through his fingers, caressingly. And the next year, when Sybil had it bobbed she saved ail that was cut away, in memory of Jok1’s kisses on it. “Sybil—SYBIL!” “Oh, John, I love you so.” kBefore she went they had planned to be married that week. Sybil drove home with her head in a whirl and her heart full of warm gladness. John would get a furlough. Perhaps the family would let them have the place at Wi- anno for a few days. That would be lots more fun than a hotel, or traveling. And she would get breakfast morn- ings—ponovers and muffin: and puffy - omelets, golden b!'own. There would be woaderful days on the beach. And ni~hts, gloriously long. They would swim in the moon- light and lie on the sands afterward. Sybil had a private conviction that a week of love in where she kept her trinkets, under the puffy blue satin pad that lined the cover. And when she slipped it there, a crushing sense of finality came over her. As if that was the end. As if John Lawrence had perished with his last crumbling protestations, and she would never see him again, And that night a cable came: “Missing in action.” They tried to buoy her up. To sustain their own faltering hopes. ¢ “That doesn’t mean he's dead, Sybil. Probably he's in a hospital somewhere. Oh, my dear, you mustn’t take on like this! Don’t give up hope. Everything may be all right” But Sybil knew ' better. “He’s dead!” she shrieked through her tears. “Dead, I tell you! I know. He came to me in a dream, all blood. So I know, you see, that he is dead.” After the war life had been very gay for Sybil's crowd. John Lawrence was 10 months missing then. “Presumably dead,” the record said. Tad came home, romantically bronzed, and “different” looking. Something about his eyes, and the gray streak that ran through his hair. He was very sweet to Sybil and talked to her of “deathless glory” and “heritages.” He gave her a bit of verse of Alfred Noyes’ that he had clip- ped from an English paper ‘n Paris, and Sybil carried it in her purse until it crumbled to pieces. But all the time she knew it was a Grand Pretense. The world was full of noble words and fine phrases. Peo- ple thought they meant them, but they didn’t really. They could tell her John died for humanity till they were black in their faces. She knew he didn’t want to die for humanity, or glory—or anything else. He wanted to live—for her. It wasn't fair. All the talk about “sacred trusts” and “making the world safe for democracy”! Peo- ple couldn’t really mean it, or they wouldn’t forget so soon. Nothing seemed to make much difference, except having a good time. Everybody wanted a good time. Even Tad. Hé looked so handsome in uniform, with his swagger English cap, and his silver shoulder bars. Tad had come home a captain. with a Croix de Guerre and two wound stripes. His mother was tremendously proud of him, and wanted him to go everywhere with her. She hated to have him get back to civies, but the second day home he went to his tailor for some new clothes. “If you knew how I hate the sight of the damn things!” he said of his beautiful whipcord breeches and his gorgeous blouse. Sybil wanted to wear mourning jor John, but the family had dissuaded her. “Since your engagement was never announced, dear,” coaxed her mother, *I really think it would be rather poor taste. Nobody reslly knows, you see, that you were ac- tually planning to_be married.” 3 “But I want the to!” cried Sybil. “I'm so proud of having been his swegtheart. | WANT everybody to know. And ‘taste’! What do I care about ‘taste’!” She took John’s picture and crossed two little flags above it, and kept it on her dressing table with flowers in front of it. She read his letters constantly, and abandon- ed herself to a frenzy of extravagant grief. “Can’t you try to snap out of it, Sis?” begged Tad. “It _ isn’t doing John any good, you know. He wouldn’t want you to take on like this. And it's pretty tough on Mother. You’re too darn smart to go dragging ’round like an old woman. It's.a good old world, after all. And we're only young once.” He brought men to the house, and urged her to make wp parties.’ ¥ “We're a girl/short. Sybil,” he used to say. “Dick’s girl went back on him. Won’t you fill in like a good sport? Dick. Wright—you know. He'’s a prince of a fellow.” Of course, she saw through Tad, but to please him, she went some times. The Eighteenth Amendment had been passed, and drinking was becoming lamentably smart. Flasks had come in; and a really daring present for a man to give a girl was an enameled flaconette for her bag. Girls had be- gun to smoke, too. Men were saying you never knew whether a girl would be insulted if you offered her a cig- aret or offended if you didn’t. Soldiers everywhere had been mustered out of serv- ice, and women were still feting them. Doughboys walked where angels feared to tread, and gobs were household pets. It was eminently respectable for “nice” girls to scrape acquaintance with men in uniform. The marines had become social lions, Everywhere the ex-service man was sitting pretty. Unless, of course, he happened to be incapacitated, or looking for a job., Club women were beginning to get excited, and talk reforms. For a crime wave hit the country. ... And even the girls were going crazy. They rolled their stoek- ings, and checked their corsets when then went to dances. Eventually they discarded them altogether, but that was not until later. Cosmetics sprang into favor, and women began to make up like Jezebels. “The evils of the war” became a sort of slogan. Peo- ple talked despairingly of “the youth of the land,” and wondered what they were going to do about it. Important persons were interviewed on what they thought of the Modern Girl. Desiring to be broadminded, they eulogised her, not knowing what it was all about. And, meantime, she went from bad to worse. Someone had coined the word Flapper. And the Flap- pers, little sisters to the War Brides, took to dressing ex- actly alike. They wore colored skirts of hom frayed about the bottom, instead of hemmed. Brilliant little sweaters that they called slip-ons. Flat-soled shoes—every- one, until then, had worn high heels, And large hats with flat crowns clapped on the sides of their heads. They eut their hair, and called it Castle Clips, for Irene Castle, who had lost her own after a fever, and wore what she had left short of necessity. Brothers of the ex-service men began to grow up. They were, for the most part, a decadent lot, their defici- encies emphasized by contrast. They were called Parlor Snakes, Cake Eaters and Lounge Lizards. At first they went in for skimpy, pinch-backed suits with high waist lines. They cultivated a carriage that rivaled the Debutante Slouch, and became Dancing Fools with long hair. When the Prince of Wales visited America, they Ch:d?led their sartorial effects, and embraced baggy models. Girls became independent. Married women, who had found work “for the duration of the war,” discovered that they liked it. Their incomes often doubled, and sometimes tripled the family budgets. Younger girls went to work. Daughters of the “very best families” entered business colleges, Commercial schools becare smart, and a work- ing knowledge of shorthand ranked conversational French. Married women, in business and the professions, retained their maiden names. Miss Brown when che became, legally speaking, Mrs. Smith, remained Miss Brown. Plain gold bands grew slimmer, and about the time the jewelers had succeeded in popularizing platinum, wedding rings were temporarily passe. There was much discussion about Free Love. Tad became involved in an “affair.” The girl threat- ened suit, and Mrs. Thorne had a nervous breakdown. The “Young Thornes” became the talk of the town. Everyone knew about Sybil's indiscretions but her nts. They knew, for instance, that Mrs. Van Dusen had threatened to sue her for alienation of philandering Van's affections. Sybil had laughed when she heard about it. ' “They have to prove very specific things in a suit like that,” she said—“and I may be an egg, but I'm not THAT kind of an egg.” People knew of Colonel Bixby’s infatuation. But they knew, too, that Sybil, when he kissed her one night, slapped his face, and told him to go home to his wife. The colonel told it himself, in his cups. To be sure, Sybil was doing any manner of foolish things. One day she took out a marriage license with Bunny Faxton. The intentions were printed that evening in the papers, and when reporters called at Thorne'’s place onI Bleacon Hill, for pictures and a story, Sybil met them calmly. “There’s nothing to it,” she announced. “The erowd was drinking, and they dared me. I'm awfully sorry and ashamed. But, truly, it was only a bet.” Of course, the papers played it up. There were front page stories, and headlines, with Sybil's remarkable state- ment in red ink. Mrs. Thorne wept, and Mr. Thorne raved. Even Tad showed considerable concern. “There are some things,” he told his sister, “that de- cent people draw the line at.” And for three days he treated her with cold disdain. Then there was the party where Trixie Belle, from the Midnight Follies, impersonated statuary in the nude. The newspapers_obtained the names of “those present,” and lo, Sybil Thorne’s led all the rest. Loyally Tad defended her to their parents. “She’s all right,” he said. “She’s only acting crazy. Grief has turned her head a little, I think.” “Sorrow should make a woman finer,” reminded his father, sternly. “It's only fiekle girls who take to cures such as Sybil has.” “People will start talking first thing we know,” wail- ed Mrs. Thorne, in her innocence. At heart, Sybil was thoroughly miserable. “I think,” she told Tad, “that God really meant me to g: g fiood girl, I've made such an awful bungle trying to ad.” Girls of her old crowd had become the Younger Mar- ried Set. A few years later they were the Younger Di- vorced Set. Tad and Sybil were driftih( apart. “We're a couple of eggs,” she told him affably one d.iYéd i And stretching himself lazily, he retorted good na- turedly: “You are making a bit of a fool of yourself, old girl. Why don’t you marry Craig Newhall?” People that summer had come to regard y New- hall as Sybil’s particular property. Most girls m have been delighted at the assumption, for Craig was probably he most eligible bachelor in Boston. Either because he was exceptionally clever, or because of his social connections, he had been admitted, fe his graduation from Harvard, to membership in the finest legal firm in the city. He was l&ngd ahnd thin, and brown like coffeé with cream in it. And his eyes were amasingly blue. When he looked at her contemplatively, Sybil Jvm thought of a bit of a jingle: “Blue was the sky, blue as your eye Which is the terrible reason why It’s easy to live, and hard to die.” Now she glanced curiously at Tad, “Why, Taddy,” she parried, “nobody’d want to marry me. I'm just a—a—" o Irresolutely she paused. How much, after all, was it wise for a girl to %oh;bmf