New Britain Herald Newspaper, March 22, 1927, Page 19

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

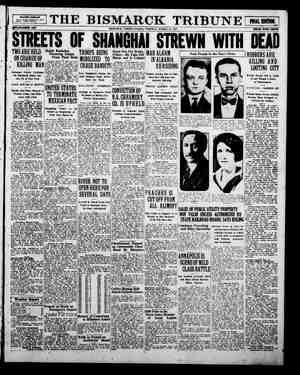

PARIS. N the drowsy little village of Forges- les-Eaux, which is in the heart of Normandy, they can’t believe even now that their own Marie-Louise Fou- quet, of pleasant memory, and the no- torious Marilly de Saint-Yves of the Paris half-world are one and the same girl. But the matter-of-fact gentlemen at police headquarters say there is no doubt of it, and she has admitted it herself. It is only five short years ago that Marie-Louise was queening it over her adoring fellow-townsmen in quaint Forges-les-Eaux, which her aristocratic ancestors had owned for centuries and of which her stern old grandmother was the unquestioned ruler. Yet it is doubt- ful that the intimates of her girlhood would recognize the girl that was in the woman that ‘s, as she broods all day in a cell in the prison at Versailles, await- ing trial for the stabbing of her lover, Licutenant Pierre Casanove. No swifter or more dramatic descent into the depths of the half-world has ever come to the attention of the authorities, A fall all the more remarkable be- cause of the girl's many- sided nature, and the fact that she possesses real culture and a passion for learn- ing. A perfect little sermon in tabloid on the im- passe at the end of the easiest way and the inevitability of the wages of sin, which is death. Marie-Louise Fouquet's father died when she was little. Her mother quar- relled with his mother and went away, never to return. Before she could talk, Marie-Louise was bereft of a mother's care and a father’s love and was com- mitted to the custody of her grand- mamma, Madame Trancard, the iron woman of Forges-les-Eaux. > Madame Trancard was of the best blood of the Normandy hamlet, where blood is everything, and the peasants trace ancestral lines back to the Cru- sades. In addition to breeding, the stern old woman had means, and owned farms and orchards and grist mills. To her humbler neighbors her word was law. In her queer, quiet way, the old woman worshiped her granddaughter, and did the best she could for her. But there was one gift Madame Trancard lacked to make her the perfect grand- mother. She was wanting in under- standing. While Marie-Louise was little, the relations between the grim old dowager and herself were perfect, but when the girl reached fourteen and began to ask questions of life, the old woman and she parted spiritual com- pany. It was the ambition of Madame Tran- card to keep her treasure with her, edu- cate her in a neighboring convent, marry her off to one of the solid young squires of the countryside, set her up as the social dictator of that small town. But Marie-Louise had other ambi- tions. In her cell at Versailles she ad- mits that she wanted to “see life,” and old Madame Trancard did not know how Lieutenant Pierre ve, the aviator who was nearly killed by Mlle. Saint- Yves just as he was about to leave her forever Mlle. Marilly de Saint-Yves, the French girl of good family Paris to “amuse herself” and has amazed the city with her extravagant follies to compromise with her for her own happiness. Never a trip to Paris, never a theater or a masked ball! Always the provineial society the spir- ited and precocious young woman found so boring. At fifteen, Marie-Louise Fouquet ran away from her grandmother and the good but old-fashioned folk of Forges-les-Eanx and made her way to Paris to “seek her fortune.” She had only a few clothes when she arrived and a few pieces of silver. Later Madame Trancard grudgingly made her a small, temporary allowance, realizing the girl must live her own life and had no intention of returning to Normandy. Only fiftecn and alone and unguided in the gayest city in the world, the strange child spent her first year “look- ing on” at the night life, also learning Spanish and German, reading abstruse books on all sorts of subjects, and pre- paring herself for a degree in philos- ophy. She actually reported at the university and asked to be assigned to classes, but was rejected at the time be- cause it was felt she was too young. In her sixteenth year, the little girl from Normandy came into a small amount of money unexpectedly and began to explore the Latin Quarter for herself. Of course, it was only a short time before she had formed a friendship with another girl, and, of course, the other girl was older and more sophisti- cated than was she. “Madame” Rossignol, Marie-Louise’s new acquaintance called herself, al- though the police say matrimony was one of the few things “Madame” never tried in the course of her lurid career. Since then, La Ros- signol has admitted that the girl was as innocent at that time as when she left her home in Normandy. The older woman will not admit she had it in mind to exploit that innocence and youth and beauty for her own ends, but the police are satisfied that she had It made very little difference, in any case, because when the time came for Marie-Louise to fall in love, she chose her own lover, and he was not a man of wealth, able to dower Madame Ro nol for her good offices as go-between. He was Lieutenant Pierre Casanove, a bril- liant young aviator, of moder: Once she had accepted Ca her lover and lived openly with him, ¢ mea nove . - Pay theWag How Marilly de Saint-Yves Faces the Law’s Penalty for theAlmost Fatal Stabbing With W hich She Ended Her Folly-Mad Career in Cafes and Night Marie-Louise dropped the name by which she had been christened and bec:ime known in the atin Quarter as Marilly de Saint-Yves. 1d with her name she dropped the last red of outward respectability and set forth to dazzle the most blase corner of the most worldly wise city in the uni- verse by her daring. it after night, gorgeously dress she appeared in cafes, studios, hot veady for anything. Her costume was copied by actresses. Her original dance, performed on top of a table, became the Montmartre. Crowds followed when talk of he went out in the evening. referred openly to her af- anove. A clever derelict of the Quarter wrote song about her—a ribald song, entitled Marilly! Oh, la! la!” Every- it until Marilly Then they stopped. with Casanove pro- body sang or whistled ot into trouble As her Copyrieht. 1921, by Johason Festurcn y- 0s of 3i Mme. Rossignol, who revealed to Lieutenant Casanove's family the truth about the notorious life Mlle. Saint-Yves was leading gressed, Marilly left her little room at the pension and went to live with him at a luxurious apartment in the rue de Noailles. Where the ardent and irresponsible couple got the money to pay the rent it would be hard to say. The apartment became the center of attraction for the most dissipated and reckless of pleasure-seekers. Strains of music floated out of the win- dows at all hours of the day and night. Bacchanalian laughter echoed through the corridors. Neighbors com- plained. Gendarmes came and went. 1t could not last for.ver, though, and there came a day when th. girl who had been brought up among the fields of Nor- man.'y told her gay lieutenant ti.at he must marry her. His family, al- tho gh not rich, was well placed, and inquiries were begun. In the first place, detectives ealled upon Madame Rossignol, who had been rather out of it after the lieutenant and Marilly began going together, and she talked plentifully and to some purpose. As a result, the airman was informed his sweetheart had been carrying on af- fairs with others while accepting his pro- tection, and that she had no more claim on him than on half a dozen other per- sonable young men who attended parties at his house. Maddened with jealousy, he told her he not only would not marry her but would not live with her any longer. And he went away. That separation did not endure. The girl sent for him and told him the need for marriage no longer was urgent. She said she still loved him, and if he did not return to her she would kill herself on his doorstep. “I ean never marry you,” he argued “My father, my brothers, my neighbors would laugh me to scorn. You have not denied you have had affairs with other men.” “Then do not marry me, but stay with me,” the high-born light o’ love pleaded. “Do not leave me alone.” When he returned to her that time she was faithful to him and asked him to forego the wild parties that had been characteristic of their first life together. But to the lieutenant she was “damaged goods,” a wanton creature. He could not forget that she had shared her smiles with those others. His love had coars- ened. In gpite of her devotion and her dark, eifin beauty, he wearied of her once more. “This time, when I go away, I re- main,” he assured her, as he deeded over the furniture and left her a little cash upon her dressing table. “Do not go, I warn you, or you will be sorry,” she stormed, but she had threat- ened suicide before, and the bored leu- tenant no longer believed in her. He went into another room to finish his packing, and she followed him. Again she tried to win him back, and he re- pulsed her. References to their mo- ments of tenderness and rapture failed to soften him. And threats failed to influence him. As he bent over to pull the strap taut on a steamer trunk, she drew a dagger from her stocking and plunged it into his back. Police found her half insane when they reached the Casanove flat. The lieutenant was unconscious from loss of blood. The girl made no denial, and no resistance to arrest. « At the prison in Versailles, Marilly was allowed to rest for a day or two, and then the matrons began their in- quiries into her past. From her reputa- tion they rather expected to find she was a gamin of the Paris gutters, a girl who had climbed by right of eerie beauty and the deadly courage of her kind. When the young woman began to talk about her childhood in Forges-les-Eaux, they became interested, and eventually led her to disclose that she was no gamin of the streets but a daughter of Norman gentlefolk, the descendant of stout old Crusaders. In Forges-les-Eaux, as has been said, word of the transformation of Marie- Louise Fouquet, remembered by all from her baby days, was received with skep- ticism. There were those who said that some adventuress of the wicked city slums was impersonating Marie, and that Marie was dead. Grandma Trancard, doughty old lady, still very much alive, although crippled and deaf, said nothing to her neighbors, and did not go to the relief of the girl of the “Boul Mich,” who used to be her favorite. Lieutenant Casanove did not die after the stabbing, although as these lines are written his condition is still critical Regaining consciousness, he expressed concern over the fate of Marilly, and declared that if he recovered he would see that the charge of sanguinary assault with a knife was withdrawn. Nothing, however, of forgiving her those smiles she granted to other men. Nothing of marriage and the happy end- ing. Men marry girls such as Marie- Louise Fouquet used to be. like Marilly de Saint-Yves, they love and leave. But girls [C)