New Britain Herald Newspaper, September 3, 1926, Page 27

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

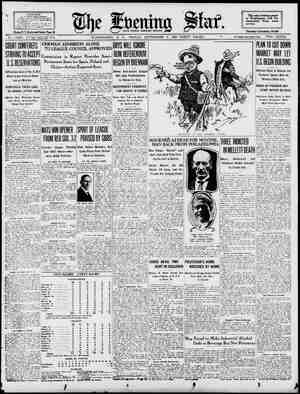

T et e This pitiful bit of human wreckage was found asleep under a pile of newspapers in a doorway. She said that the soup the Salvation Army’s “angels” gave her was the first food to pass her lips in more than twenty-four hours By C. DE VIDAL HUNT PARIS. HERE are places in the gay city T of Paris where hordes of home- less men and women may pur- chase for a little less than ten cents a whole quart of wine, together with the right to sleep pell-mell upon sticky tables or on the stone floor from ten at night until two in the morning. They are the places of refuge of the true “miserables” of the Paris under- world. According to police statistics there are between 4,000 and 6,000 of these vagrants in the big metropolis of light and pleasure, men in rags and pitifully demoralized women who feed like ani- mals upon the garbage of the Central Markets and sleep wherever they can. Not all have the price of a bottle of wine. M. Albin Peyron, lieutenant commis- sioner of the French Salvation Army, made the above statement to me and offered to prove it. We met one night at ten o’clock in the Place Maubert. It was bitter cold and dark as pitch. Three women Salvationists joined the party. Peyron, in order to keep his hands free for his accordion, gave me a small load of pamphlets and his purse to carry. Some indelicate person had relieved him of his pocketbook one night while his hands were busy with his accordion. We started from the foot of the austere monument to Etienne Dolet, printer and philosopher, who was burned at the stake on that gpot in the sixteenth century, and moved down the somber alley of Maitre Albert into the old Dante quartier. It was there that the exiled Dante lived in dire wretchedness about the time he began work on his immortal “Inferno.” : On the corner of the Rue du Chemin Vert we met the lassies with the soup wagon. Presently, in a deserted spot we almost stumbled over an old gunny sack. One of the women knelt beside it. “Would you like a little warm soup?” she asked. Faintly the bag trembled. Slowly it rose. Under it was a man. The Sal- vationist repeated her question in a soft, well modulated voice. The man shud- dered, opened wide a pair of tired eyes. He seemed unable to understand, but at last he tremblingly held out his hand into the ray of scarchlight before him. It was an old emaciated hand, grimy and deformed from years of suffering. The man did not look up. His vacant stare was riveted upon the steaming tim cup which the little woman offered him. EveryW¥here around us were other, dark figures lying on the cold stones. We could see them now in the faint glare of the searchlights. The *soup angels,” as the Salvationists are called, did not miss a single one. There was soup for all. Those that had bags to sleep under How the Salva- tion Army’s " Tireless Soldiers ’ Search Out the Miserable, Homeless Derelicts and § Relieve Their Cold Hunger With Cups of Steaming Soup and Carrying the cheer of a cup of hot soup to homeless wretches sleeping under the tar- In cold, damp cellars, in alleyways with hard paving stones for a pillow, in the filth of stables the homeless of Paris curl up in their rags by the thousands every night and try to snatch a few hours of sleep. And in these pitiable substitutes for a home the “soup angels” seek them out night after night and do all they can to relieve their poverty and suffering were the more unfortunate ones in this_ abode of misery. Most of them had only rolled rags for pillows and soiled newspapers for covers. One raised the dilapidated coat he had taken off to cover himself with. He was stark naked down to the waist. The old man rose feebly upon his haunches and turned his white head hungrily toward us. I asked him some questions. His trembling voice came rumbling and hollow as from the bottom of a pit. “I am seventy-seven years old,” he said slowly; “my feet hurt and I can’t work. It’s my shoes that have dpme it, the old shoes the cops took gff the dead man in the Seine.” With a trembling hand the old man undid the rags and newspapers that were wrapped around his feet. “I am dragging myself along the best I can,” he went on in his sepulchral tones, “but I shouldn’t have worn a dead man’s shoes. I am picking up old papers and sell them to the rag man. Often I find something to eat in the garbage cans.” The man had lost even the strength to complain. A little farther aown the alley a woman rose to her Jeet, haggard and dramatic as a maniac. “Any soup to-night?” she shrilly. “Any soup?” The woman was literally in rags. Her bloated face was twitching and her breath was heavy with alcohol. She was yelled viciously scratching her head with both hands. In a moment the sweet face, of a “soup angel” smiled right into her crazed eyes. “Have something warm, sister?” said the Salvationist; “it will do you good.” The woman clutched the soup cup frantically and lapped up the hot broth like a famished beast. What could be done for that woman? There were dozens and hundreds like her, crumpled up in dark corners and stark in a cold death-like sleep. Several police officers joined us. What could they do? There were thousands of home- less in Paris, all needy of support or shelter. The city authorities had no means of helping them. There was no room in the prisons. I had walked to the meeting place in the Place Maubert from the Park Mon- ceau that night in a little over half an hour, yet in that brief space of time it seemed as though I had traversed sev- eral centuries, It seemed like an im- possible transition from the palaces of the rich to the lairs of the stranded. The contrasts were frightful. Surely no other great city in the world can have its equal. We peeped into underground caves that were filthy with vermin. Some of the “miserables” slept there. One place looked like a morgue in which the corpses lay shivering as in a last horripi- lation of life. Copyright paulins of motor trucks outside the Central Markets The three L daughters of Commissioner Peyron of the Paris Salvation Army who assist him in his nightly ministrations to the home- less and have become known as the “soup angels” But even these poor wretches who lived in rotten holes and slept upon heaps of filth seemed better off than the vagrants on the streets. They had keys in their pockets and could say they had a “home,” while those others had no key, but often o knife. Those others were the ones who slept anywhere, but preferably in the wine caves around the Central Markets where a quart of thick red wine and a place on the floor cost ten cents. It was about half past one when Lieu- tenant Commissioner Peyron and the “soup angels” led me into La Grape d’0r, a murderous looking place near the Halles Centrales in the very heart of the city. It was a typical place of the kind, a sort of underground dun- geon at the bottom of a battered stair- case, where some 200 human derelicts, men and women, soaked in wine, slept closely huddled together. As we groped our way into the bl ness below we were struck by a.wave of fetid stench that seemed to have come straight from hell’s own slaughter house. In a dimly lit cellar, about thirty-five feet long and thirty feet wide, lay this noisome, smoke and alcohol saturatec catafalque of human misery. There were three layers of sleepers, those in the wine puddles under the tables, those on the benches and those on top of the tables. They looked like 0 many ks of coal, heaped together in the dimness of a reeking cellar. Close to the door sat the proprietress, a plain looking French business woman who rose to her feet as we entered and forbade us to sing. She said it in a nice way, evidently anxious that the sleep of her guests should not be disturbed. “Je regrette beaucoup,” she said, “but if you want to sing, you will have to t outside until two o’clock. I close my hotel at two sharp and everybody must leave. It is the law.” We decided to stay just outside the door and wait. Although the air pur- sued us like the fumes of a violent anaesthetic we held our ground, Peyron and his little band had been in worse places. Promptly at % o'clock the human 1026, by Johnson Features, Ine. L § R catafalque was shaken out of its lethargy by the stentorian voice of the proprie- tress. “Come, my children,” she shouted, “it is time for your morning promenade.” And the three black layers of sleeping misery began to stir slowly, heavily, like the lazy swelling of tar in a huge caldron. Vague figures rose from the wine puddles on the ground, women and men groaning and twisting miserably with the pains of warped spines and sick lungs. The sacks were coming to life. The awful dive was discharging its hu- man cargo. up and get out,” the pro- s urged, “or the cops will throw One by one, in pairs and groups, the 200 “miserables” straggled out into the night. At the mouth of the alley, under the yellow light of a gas lamp, five policemen watched the sad procession pass and said nothing. They could have arrested the whole miserable caravan on a charge of vagrancy. But no such luck. The homeless wretches had long given up the hope of arrest and a nice soft cot in the city prisons. Having no domi- cile and, therefore, no votes, they could not go to their representatives in the Chamber of Deputies and claim their right to be punished like any other citi- zens trespassing upon the law. They simply had to stay outdoors, winter or summer, snow or rain, and make the hest of it. Of course, those who still had a few sous in their pockets could afford to go into one of the vaga- bonds’ cabarets, like La Golee, just iround the corner from La Grape d'Or. After singing a hymn and trying to distribute a few sheets of “The Life of Jesus,” the Salvationists decided to fol- low some of the vagrants into La Golee It was a curious den we got into, some- thing like a guard house of some medie- val stronghold. On the left, as we entered, was a long bar with women standing against it. They were characters such as we see in old prints depicting the Reign of Terror. From this room we penetrated through a fine archway into what looked like & huge stone vault. Here men and women were drinking and carousing around crudely fashioned tables. Some were dancing in the nar- men and row space between tables or hugging each other until some of the on* lookers tripped them and sent’ them rolling under the beriches or tables. The place was filled with “maque- reaux” and their women. The air was thick with smoke and cheap perfume. On the walls were sketches and ecrude paintings. From this room a low arch- way opened on a flight of stone steps that led down into the “red oubliettes,” or sealed dungeons, where 400 years ago political prisoners or the victims of royal love intrigues were thrust and “for- gotten.” Now these caves were electrically lit and filled to suffocation with men and women of the lowest order. No tourist had yet dared enter this dive. The pro- prietor looked like an executioner. He raised no objection to the Salvationists’ entering the place. But he smiled cyni- cally. “Take your own chances,” he warned. “Forward,” commanded Peyron. They went to the last of the dungeons below and started to sing to the accom- paniment of Peyron’s accordion. For a moment it lookec as though two or three of the maquereaux were going to pull their knives and start something. But the situation was saved by an old drunk- ard who reeled over toward Peyron and tried to embrace him. Peyron smiled amiably and sang right on: Have you no place For the Lord in your heart? There was a howl of laughter, but the Salvation soldiers carried right on. The old drunkard then tried to sing, but only succeeded i clucking like a hen, which brought more laughter. In the meantime some of the ‘“soup angels” sold a few copies of their paper. The dancing and carousing went on and nobody paid any more attention to the intruders. Nobody except a middle- aged woman who came up to Peyron and said: “I've got a daughter over there in the corner who wants to go, but they won’t let her.” Peyron went over and spoke to the girl. T don’t know what he said, but the girl got up and followed him. No one interfered. “Take her along,” the mother begged. The girl looked radiantly into the face of the white haired Peyron. She gave him her hand. And the “soup angels” smiled happily. Their visit to La Golee had been worth while.