Grand Rapids Herald-Review Newspaper, November 5, 1898, Page 5

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

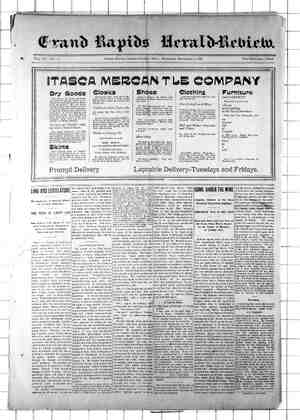

t ewer ey nee gS if f. -f 4 Supplement tes Hl RAND RAPIDS HERALD--REVIEW LIND’S ELECTION WILL REDEEM MINNESOTA’S FAIR FAME! THIRTEEN YEARS OF ROBBERY Of the Grain Growers of Minnesota, in the Grading and Docking of Their Grain. MONSTROUS REPUBLICAN INIQUITY. Shall It Longer Be Endured?—Review of the Whole Wicked System—Rotten to the Very Marrow—Our Producers at Last Aroused, and in Their Mighty Majesty Will Sweep Their Oppressors From Power. Caniinlats Eustis and His Relation to the Elevator Ring | —The Mighty Grain Rings Exposed, Which Would Control His Administration. Read and Be Convinced, and Trust John Lind To “Turn the Rascals Out..” 4 The perversion of the open market in which Minnesota grain growers di: posed of their produce in the early days, when the buyer sought the seller, to the present condition, when the sell- er of grain seeks the buyer, is one of the striking features of our modern commercialism. When labor hunts employer its remuneration is inevitably less than when employer hunts labor. When the man who has something to sell has to go offering it to dealers he is sure to get less for it than when the dealers come to him. Before the days of line elevators and millers’ associa tions and state systems of grading and inspection the buyers of grain went down into the streets and met the farmer and mounted his wagon and sampled his grain and made th for it. No one heard the word “ spoken, although each bidder was mak- ing his personal judgment of the grade of the grain the basis of his offer. When the price offered met the farm- er’s judgment of the value of his grain the sale was effected. hat was the free and open market. It is many a long year since it passed away from the Minnesota farmer, largely with bis own assent. Instead, we have to-day in each local market town the agents of the elevator companies sitting at the doors of their elevators waiting for the farmer to come to them. There is no competition among them. The price is the same at each for the same quality, and if one offer a better price than another it is because he judges the grain to be of a better quality than the others. The re- sult is a tremendous change in the commercial position of the farmer and in his own conception of himself as a factor in the great world of production and exchange. He no longer has, no longer can have, that sense of inde- pendence that he felt when his grain was desired by men so anxious to get it that they met him, bid against each other for it, and narrowed the margin of profit for themselves while widening it for him. , How this change has come about, has grown the “line elevators” that practically monopolize the grain mar- kets. It is the duty of common car- riers to receive and forward freights proffered them. It is further—and this is the point of the whole matter—their duty to supply suitable appliances for the convenient, safe and speedy per- formance of this duty. This duty they perform for all classes of freight ex- cept grain. They bnild warehouses for merchandise, construct pens and shutes for handling cattle, supply refrigerator cars for carriage of perishable articles, and, generally at their terminals con- struct elevators to receive and store grain. But-to the grain grower who would ship his grain, or to the buyer not an agent of a line elevator, the rail- ways refuse to furnish that essential appliance in the reception, handling and shipping of grain, the local cleva- tor. The railways are not blamable, as human nature goes, for avoiding the added trouble and expense that the performance of this part of their func- tions would involve, but it is remark- able, if we accord them sincerity, that legislators, while trying to force upon railways tasks foreign to their pur- poses and to prevent them from doing that which, in other lines of business is legitimate, have never once dreamed of compelling them to resume this most important part of their work in the handling of grain. ‘When that is done, when local buyers can haye suitable appliances furnished them for hand- ling the grain they buy, the so-called “grain problem” will be solved. Throttled Markets the Consequence. The inevitable result of this relin- quishment of a legitimate function to private individuals by the railways was the formation of corporations to build, own, and operate lines of ele- yators along the railways that channel the great grain-growing sections. For a time some one firm had the moropo- ly of grain-buying on most of the roads. . Railways safeguarded this monopoly by refusing space for build- ing other elevators on their right of way. Forty and 50 and more per cent what of it is due to the tendency of | dividends, earned by these monopolists, business towards concentration and combination, what to legislation where responsibility for it can be fixed, and what, in the forum of party politics, the farmer can do to recover his inde- pendence has been a subject of pain- ful interest to the farmers of the state for years, increasing in acuteness as measure after measure has been de- vised and enacted to remedy, but only served to aggravate. It is worth the while of every grower of grain in the state to trace the effects of the legisla- tion that has been enacted, as well as that not enacted, for that is one of the causes within his control, and to study the subject with a view to discovering the conditions that.haye wrought this change andthe remedies that will re- store freedom and competition to his market. The Railroad’s Share. The change, hardly noticed in its be- ginning, not yet fully appreciated, but which contained the germ of all subse- quent development, began when the 1ailways found it to their advantage to permit individuals to take over one of their functions towards grain handling and shipment. All that has followed became possible when railways threw off the business of receiving and for- warding grain and let that function pass to persors, and inevitably to cor- porations, who constructed elevators, merged them into “lines,” and gradu- ally centered the vast business in few hends. The conditions facilitated the natural tendency of competition to end in combination. The elevator sites, be- ing necessarily on their right of way, gave the railways the power to decide who should and who should not con- struct and operate them, a right that has been sustained by the courts when legislation attempted to compel them to permit the erection of elevators by anyone wishing to build. Out of this formed a pressure too strong to be re- sisted, and other “lines” were formed and built. The competition in buying was but temporary. Why should these buyers cut off their own noses? Why diminish their profits, when they could diminish those of the grain grower in- stead? Human nature is selfish; grain ‘dealers are not philanthropists, and, however much solicitude for the farm- er they may profess, they are not neg- ligent of their own interests. Thus came about the condition of affairs de- velcped and exposed by the Democrat- ic State Central committee in 1892, in the pamphlet, “A Gigantic Conspira- ey,” printed and distributed for them that year. Hence came the exposure of the abuses made by the legislative committee appointed by the legislature of 1891, that showed how, under form of law, aided by laws whose pretended purpose was to protect the grain grow- er, the producers of grain were robbed. One man in Minneapolis, acting as the ; agent of the line elevator companies, ; Sent out daily to the agents along the lines, by card or wire, the price to be paid for grain. Confronted with the statement made to foreign bankers of the profits of the combination, Mr. Amsden, manager of the Minneapolis & Northern Elevator company, operat- ing 140 elevators, admitted profits of his company ranging from 20 to 42 per cent. The profits of the Northern Pa- cifie company were stated to be 36 per cent; the average profits for six years of the Northwestern company had, been 22 per cent; the Van Dusen com- pany reported profits ranging from 22 to 28 per cent. When a combination can have the unchecked control of the market of any article; when it can fix the prices paid for millions of bushels of grain; when it can have established by state authority arbitrary grades for grain with no state authority to deter- mine the grade at the point of pur chase, it has the grain grower by the throat, and with its grip can throttle the market. Like Jay Gould, they ad- just the conditions so as not to kill the traffic, and, like him, take for thém- selves all there is ‘in the grain business except enough to keep the producer | alive. The Farcical Remedies. Thirteen years ago a Republican leg- islature, spurred by the complaints that came up in ever-increasing vol- ume from the farms alarmed by the advent of the Alliance as a political factor, attempted to devise and apply a remedy. They took conditions as they found them. They did not attempt to remove any that worked to produce the abuses complained of. They left the railway surrender of function un- touched. They left the local markets in the control of the combination of line elevators. They provided for a state inspection of grain, not in the primary, but at the terminal markets, The railway commission was made a grain and warehouse commission also, and given jurisdiction. A chief grain inspector was created, with a staff of deputies and weighmasters and clerks. The inspectors were to be “experts” in judging the quality of grain, and their function was to inspect all grain arriving and assign it to the particular | one of the several grades fixed by the grain and warehouse corffnission. One member of the first commission, asked how an inspection of grain at a terminal point, hurdreés of miles from the local market and days and weeks after the producer had there sold his grain, could be of any possible help to , that producer, replied that “the com- | mission men had been thinking” of that feature of the situation, and that | it had found no means of helping the | farmer except by sending out state-- | ments to the local elevator of the grad ing given grain arriving at the termin- als. In Spite of This Plaster ; The sore refused to heal. With each | succeeding crop the complaints grew | louder and louder. Then came the in- | vestigation of the Democrat-Alliance legislature of 1891, begun at a time when no campaign was on, with its astounding disclosures of downright robbery. In the succeeding campaign | of 1892 the Democrats made grain in- spection an issue. How did the Re publicans meet it? By admitting the | aecuracy of the charges, but asking | thd farmer if it were not better to stand the abuses until a Republican governor and legislature could be elect- ed to devise and apply a remedy, than it would be to elect a Roman Catholic governor, who would*appoint a priest state superintendent of schools and ap- portion the school fund among the par- ochial schools. Astounding as it may seem, this trick actually succeeded. Mr. Nelson, then Republican candidate for governor, plead for votes, promis- ing that, if elected, a complete and ad- equate remedy should be found and provided. How, he asked, could a par- ty whose legislature had spent more money in its own expenses than any other preceding one, be trusted to han- dle so momentous a question as the grain problem? The result of all this was ‘a decision by a majority of the grain growers to trust the Republican party once more, to give them the re- lief they so sorely needed. The Farce Revised and Enlarged. The legislature of 1893, by a dicker with three Alliance senators, was sol- idly Republican. Plenary power was given that party to correct all evils in the grain business. Goy. Nelson, in his message, virtually admitted all that had been alleged against the state sys- tem. He pointed out its weak point, the terminal inspection. He said it was the bonanza farmers and dealers who shipped directly to the terminals, “but the ordinary farmer, he who is unable to ship in carload lots, and is obliged to sell his grain by the wagon- load to the local dealers—and most farmers belong to this class—he has no state umpire, either as to grade, weight or dockage. No state weigher or state inspector is at hard or can be invoked to right his wrong, if any; but he is re- mitted to the vague and dilatory reme- edy of the common law.” Could the helplessness of the grain grower have been more graphically depicted? Did the Democrats make a more complete demonstration of the inefficiency of the grain laws than did this Republican governor in his inaugural? He ad- dressed himself to concocting remedies. The docile legislature registered his prescriptions and made the state laws. We find no less than five chapters of the Gereral Laws of 1893 devoted to regulating the grain traffic. Chapter 28 is the law that, amended and en- larged in 1895, made every country el- eyator a public elevator, to be licensed by the grain and warehouse commis- sion and be under its control. Chapter 29 provided for the protection of grain in cars at the terminals. Chapter 30 provided for the erection of a state el- evator at Duluth, afterwards declared uncorstitutional by the supreme court. Chapter 63 provided for the right to build elevators by any person, firm or corporation on the right of way of any railway, an act also held to be violat- ive of the constitution. Chapter 65 re- quired railways to build a side track to any elevator, warehouse or mill, at its own expense, that was within a certain distance of the roadway. Surely, here were plasters enough to heal any sore, medicine enough to cure any disorder. Chapter 28 was the masterpiece. é It was said at the time that it had the approval of the line elevators. Cer- tainly there is nothing in it to which | SEA | ee OF THE ELEVATOR RING AND CRAIN POWER OF MINNESOTA. = CHAMBER OF COMMERCE AND W. H, EUSTIS’ FLOUR AND CORN EX. CHANGE BUILDINGS IN MINNEAPOLIS. “Eustis Corners,’’ and the Tenants and Political Friends Who Will Aid Eustis to “‘Reform’”’ the Crain and Warehouse Commission. The agitation for the remeval of the Chamber of Commerce elsewhere, which would lose Mr. Eustis his tenants, would not lessen the disposition of Eustis as Gover- nor, to favor them in the Grain and Inspection Department ! The Buildings—That on the left is the Corn Exchange, occupying the southeast corner, and is immediately opposite the Chamber of Commerce. | The latter is where the operations of | all the Minneapolis grain market are conducted. Opposite the latter, across Fourth avenue, is the Flour Exchange. This building figured in the campaign | of 1896, being used by Mr. Eustis in his anti-silver “arguments.” For this! he pleaded with tears in his eyes as big as walnuts, not to vote free coinage | on him, so that he would have to repay | the friend from whom he said he bor- rowed the money to build it, in “50- | cent dollars.” Of course, William ! would “have to” pay his friend in poor | money. Then he pleaded for McKin-! ley’s election, so that he could go on! and build the remaining stores of the | building. He now tells of the arrival | of the “prosperity,” but the building remains sawed off a little above the floor of the Pv system, just as it was when it was stopped, about the time that the Sherman silver coinage act was repealed. * W. H. Eustis is a Member of this | Chamber of Commerce, though the | membership list gives him as a “law- | yer.” There are only four other law- yer members, out of a membership of nearly 600. Mr. Eustis’ Tenants.—The following grain and elevator firms and concerns are located in the Eustis buildings, Corn and Flour Exchange: | Peavey Elevator Co., occupying the | whole floor of Flour Exchange. J. Q. Adams. Barnum Grain Co. Belt Line Elevator Co. | Central Elevator Co. Duluth Elevator Co. Dunwoody Grain Co. Globe Elevator Co. Interior Elevator Co. Harver Grain Co. McCord Grain Co. McCall-Webster Grain Co. Minnesota and Western Grain Co. Monarch Elevator Co. Northern Grain Co. Pacifie Elevator Co. Osborne-MecMillan Elevator Co. Kenkel, Todd & Bettington Elevator Co. F. H. Peavey & Co. Pohler Elevator Co. Republic Elevator Co. St. Anthony Elevator Co, St. Anthony & Dakota Elevator Co. St. Paul & Kansas City Grain Co. ‘Thorpe Elevator Co. Westall Elevator Co. Woodward & Co. Woodworth & Co., E. S. Cunningham & Crosby. W. O. Dodge & Co. J. E, W. L. Luce. G. F. Moulton. Tromanhauser Bros., Elevator Build- j ers. Finally, most appropriate to the cir- cumstances, and completing the dom- inating influence of Eustis, Minnesota’s Republican Grain and Warehouse De- | partment, are tenants, to-wit: State Grain Inspector, State Flax Inspector, and State Weighmaster C. M. Reese, occupying large space in the Corn Exchange, The same grain and elevator interest made Eustis the candidate for Gov- ernor. Their money carried the Hen- nepin caucuses; their pricipals or rep- resentatives sat as delegates in the state convention, and made the deals and did the wire pulling which secured Eustis’ nomination over Van Sant and Collins. The following were such, nearly all Eustis tenants, who thus made him the Republican candidate: F. H. Peavey & Co. Charles A. Pillsbury & Co. Minneapolis Mill Co. St. Anthony & Dakota Elevator Co. Minneapolis & Northern Elevator Co, Van Dusen-Harrison Grain Co. Peavey Elevator Co. Dunwoody Grain Co. i St. Paul & Kansas City Grain Co. St. Anthony Elevator Co. Pillsbury Flour Mill. Empire Elevator Co. Atlantic Elevator Co. Monarch Eleyator Co, Central Elevator Co. Globe Elevator Co. Interior Elevator Co. Republic Elevator Co. G. F. Moulton. Tromanhauser Bros., clevator build- ers. Grain Corporations. Of these F. H. Peavy, head of the Py system was present in person, though in the convention on a proxy. Charles A. Pillsbury was present in person; also G. F. Moulton, W. H. Dun- woody and Mr. Trumenhauser. Others were represented by agents, attorneys or employes. Thus ex-Attorney Gen. Geo. P. mn, represented the Van Dvsen-Harrington Grain Co. Gen. Wil- son, who is also attorney for lumber Millionaire T. N. B. T. Walker, is can- didate for the legislature. This same elevator Grain ring interest had full charge of the Foraker exposition meet- ing, furnishing the money therefor, and turning out their employes for the “reception” parade and exposition “demonstration.” erry: they could object. It did not touch { them. It left them free to by grain, fill their elevators and have no room | for the occasional, venturesome, trust- ing farmer who might want to store or ship his grain. It is also significant ‘of the influences that have shaped all ! this legislation that, when this bill was | introduced it was objected that it did not provide for the regulation or con- trol of the terminal elevators, whence came a large portion of the complaint. It was said that these required differ- ent treatment and that another bill would follow relating to them. If it followed it never got birth. It was all right to fool the farmer with a preten- tious act regulating country elevators that was not worth the paper it was written on, but when it came to inter- | fering with the terminal elevators, that was, as the Germans say, “a ganz andere sache.” It is also worth noting that the senate started a farcical in- vestigation of the relations of the rail- ways to grain transportation that ended as intended, discovering nothing, but leading the farmer to think something was being done for him. That all these remedies, including the revision of the country elevator act of 1893 by chap- ter 148 of the Laws of 1895, were ut- terly ineffective, that they did not touch the disease at all, is demonstrat- ed by the complaints that came in- creasingly with each annual crop since. “The ordinary farmer” was left as un- protected ‘as he was described to be by Governor Nelson in his first mes- sage. The local elevator undergraded his grain, overdocked it and under- weighed it. He still had to sell his grain days or weeks before the state’s agents at the terminals inspected and graded it, and whatever they did could by no possibility help him, for the grain when inspected no longer be- longed to him. If there is to be an inspection for the benefit of the farmer it is arrant nonsense, or worse, to have it at any other time or place than when the farmer is offering it for sale. This is as plain as the nose on a man’s face. ‘The Same Old Story. So, in this year 1898, thirteen years after the Republican doctors began treating the sick wheat patient, we have the patient telling of the same old aches and pains, the same symp- toms. Again the protests pour in against a system under which farmers are robbed without redress and in spite of the guards against theft erected by Republican legislation. Farmers meet in convention and their committee pre- sents an array of proofs that establish irrefutably the facts of robbery and of the utter inefficiency of the system os- tensibly created to prevent it. The JOHN LIND WILL PUT AN END TO RING RULE AND ROBBERY! io aR ease : / 1 if i i we saree