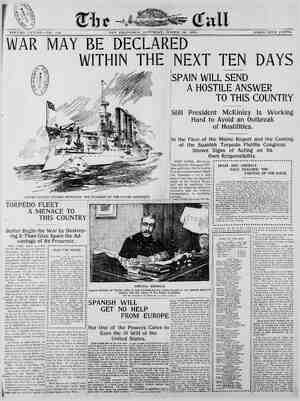

Grand Rapids Herald-Review Newspaper, March 26, 1898, Page 2

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

: —F & E 5 OIG HEE HOI IE IO OR OK OE HOE HO s THE SECRET EOF A LONELY HOUSE. § RE SE CHAPTER I. “You are sorry to leave Riverside, 1 am_heart-broke! ex- 1 ‘the girl addressed. ‘o have dear X Fenwick, and all my companions, and be obliged to ive until | am of age in the house of a crusty: old man of whom L of his two re, 1 shall claime: to leave you, . Whom, I am su » The prospect is terrible! -. ‘Thunder is your second cousin, my dear appointed your guardian when your father died—ten : s; ago. As you have never seen 4im, Pansy,” urged the elder lady, mall luncheon basket for packing a ny find he the young tr improves on acquaintance “He cannot well be more uncongenial than I have pictured him, ¢ ertainly,’” Vereker, ruefully. “IL am . if there was any good in any of them, the y would have written to or sbowed some interest in me during all thes: As it is, I have learned to regare y home, and you, dea Miss Be sawic k, as almost my second another. And Pansy embraced the good lady, and they mingled their tea for the parting was inevitable, and might, as of them see, be foreve! was a low, irregular white stone building, surrounded by a large, well matured fruit and flower garden. It stood upon rising ground, about fifty yards from the river, and was sit- uate at ‘I'wickenham. asy had grown to love every inch -shé of the place during the ten year had been under Miss Fenwick’ at Rive and full of happine: ASU In short, she knew home, having never once holid: even, elsewhere had entered the house—a maiden of about seven Her life eventful, quiet pl ne other spent the since she small, shy yea “And your cou sins, the Mis es Thun- do you ‘think seem to hi heard, though w hen or where L can’t remember, that eousin has been married — twice. Whether these girls are the daughters of the first or second X Thunder I do not know,” said Pansy. “And Yhunder, too! at an extremely dis- quieting, unpleasant name! Black Te arn Gra nge does not sound inspiring, Fenwick admitted that the mame was not enlivening. “Dear Miss Fenwick, you are So good. I am afraid that I had will, I should tire even your hospital: ty out, for I should like to live at Riv: de always. When I come of ag which will not be for nearly four y though, I shall : you to let ne take up my abode permanently with y We will enjoy ourselves, for I s have lots of money to spend, and noth- ing to do with my time. give up the school, and when w rot living at Twickenham, we travel togethe our own jolly much mone Miss F ever knew “Your father left one hundred thou- sand pounds, my dear child,” said the ely and that has been will and see the world in independent way. How n leave me, dear have forgotten, if I umulating in the fun for ten so you will be a very great s, my little unsy. I pray and trust that you may to choose wisely, have the foresight for you will have many suitors, chitd, and you are too in- experienced to discriminate.” “T shall never marry,” laughed Pan- sy, “because I am so handicapped by my fortune that I shall suspect the motives of all my admirers, and give them the credit. indiscrimnaitely, for fortune-huntin; “The brougham exclaimed Miss Fenwic her watch, “and I am sorry tos have not too much time. Good-bye, dear child, good-bye. Write to that I may know you have a safely at your destination.” And, with another kiss and reluctant pressure of the hand, Pansy entered the carriage, and w: She glanced back when the gates were past, to look lovingly and for the last time for many a long day at the old-fashioned house whieh had so ant associations for her. fast, for she felt so utter- ly frievdless and alone; and the fu- ture looked dark and unpropitious, de- spite the wea Ith which would en for her ir share of the world’s con sideration. A long journey lay before her, for Black Tarn ¢ in an obscure little village in Cornwall. Her guardian had written: “[ will meet you at Waterloo on ‘Tuesday next. Do not keep me wait- ing, my time is of consequenc>. We shall travel as far as Exeter on that and from thence on to Craig- is waiting, dear,” consulting nm sped onward— ‘ket gardens, and already the spring flowers were showing, though it was early in March. As the familiar landmarks flew past, and she neared London, her fears increased ten-fold. How could she tell what sort of peo- ple she was going to live amongst? “fhey might be worse than uncongenial —boorish; indeed, from the tenor of her guardian’s letter, she could see that he had no friendly feelings for her— that had he studied to write a cold, re- pressive letter, he could not have suc- ceeded better. She was glad when the short: sour- mey was over, and she alighted on the platform at Waterloo. In accord- arce with Fergus Thunder’s expressed -wish, Miss Fenwick had already dis- patched Pansy’s trunks, so there was no necessity for her to carry anything amore cumbersome than a handbag. She went straight to the general waiting zoom, and stood timidly warming her how old rvinced. It would be **v feet atthe fire, until, suddenly, some- one touched her on the shoulder, and said, in a harsh, deep voice: You are my ward, I believe? us hunder, your guardian.” y turned towards him in evident ntroduction. id, gruttly, in Tam Ferg PD. alarm at his abrupt | se! “On, | knew you,” he s yer to her question, “by the por- tri our governess sent to me; but you are too much like your father for me to have made any mistake. You've brought your luggage, I hope? Only this bag? That’s well, for you'll have to carry it yourself. Come along—we've me to le t tive. your ticket.” He hurried out of the waiting room without giving her time to ask any questions. She followed him as quic ly as she could, but the long, angular figure of her guardian still kept the i, and, breathless and exhausted, t length found herself in a thira- iage opposite her uncongenia taken 1 have already t troubled to exchange a word with b young ward, and, be- yond closely scrutinizing her from un- der his pent-house brows, he took but little notice of her until the train had already covered some fifteen miles of ihe journey. She, however, by dint of occasional stealthy glances, had gathered a very exhaustive impre: on of the nature and appearance of her new-found rela- tive. He was a tall, spare man of about fifty-five, of an awkward, shambling figure, upon which his ill-made and ill- fitting clothes hung loosely; his eyes, evil-looking and deep-set, were of yel- low brown, over which the beetling red brows scowled with a dull uni- formity of habitual ill-humor. “How much worse,” thought the girl, than [ ever pictured him. If his daugh- ters are equally ill-favored, how iniol- erable my lite with them will be.” As he sat poring over the dailv pa- per, she noticed that he had a nervous affection of the muscles of the f: which rendered him additionally re- pulsive. He had, moreover, a disquiet- ing habit of looking stealthily about him when he imagined himself uvob- served, On one of these occasions he sur- prised Pansy in the act of contemplat- ing him with evident disfaver. “Well, young lady, you seem at a loss for some occupation, to judge from the interest you seem to take in my per- sonal appearance. What conclusion have you ‘ived at respecting it, eh?” P: was taken aback at the sud: denness of this question, “I—1 don’t know; I have not thought about it.’ This was far from the truth, since she had already decided that he was irremidably objec nable, “If you plea: he ventured, rather relieved to the long silence, “what do you wish me to call you? You are my second cousin, I believe? You sent, I know so little of my own y, having lived all my lite nearly with Miss Fenwick.” “Well, you've seen the last of that good lady for a long time to come. A precious expense, your education has been there for the past ten years. A ‘hundred and twenty pounds a year! um for the education of like you; and Ill be ignorant as a dray horse now! What shall you call me, eh?—Cousin Fergus, to be sure. And, look here, my girl, as it will be four years before you come of age, and as L shall have to keep you at my own ex- pense during the whole of that time, you will have to bustle round and make yourself useful. I don’t suppose yowll be worth your salt for a long time; but you can be made useful, sor ehoy Fergu: the Preposterous a slip of a bound you're ‘Thunder omitted to mention that the trustees under Mr. Vereker’s will allowed him, as the girl’s guardian, five hunded a year for her maintenance, board and education, and that, by removing her from Miss Fenwick’s care he had saved a hun- dred and fifty pounds a year. Pansy looked up at him with sur- und evident indignation. “I cannot believe that my father has left me a large fortune on taining my majority, and yet made no provision for me previous to that. You must be mistaken,” she said. “Don’t argue with me,” he retorted, sharply, son.ewhat taken abeck at the girl's shrewdn “You are an ig- uorant child. One thing you cannot learn too soon, and that is that I shall allow you to have no will of your own as long as you ave under my care. Ab- solute obedience, or 1 will know the reason why ” Pansy pI but not con- r to the knife,” she saw that, and swellowed her indig- nation as well as she could. “I shall take the first oppcrtunity ot running away,” she decided, as the train flew on, mile after mile, and the grim, unbending featvres of her guard- ian confronted her, “I never can en- dvre that brute for four long years.” was silenced, CHAPTER II. Craigeerie was a desolate little vil- lage, consisting, for the most part, of small thatched cottages, with here and there a tiny shop at which all sorts of incongruous articles were sold—from a packet of pins to a quartern loaf. At the wayside station, which was a mile and a half from the village, Fer- gus Thunder and his ward duly alight- ed the day after Pansy left Twicken- ham. The girl already looked worn and Cepressed, for the uninterrupted society of her cousin was painfully lowering to the spirits. The eyening was misty and cold, and as they drove out of the station yard, Pansy felt that she had never been so miserable in her life. “Have we far to go?” she asked, glancing at the rugged desolation of the surrounding country with strong disfavor. “I’m very cold and tired.” “Eh—far to go? Yes, a good three miles, Cold and tired, are you? You'll get over that, I daresay.” Pansy relapsed into silence, and tried to repress a strong inclination to burst into tears. It was so dull, hard, cold, and utterly wretched that she felt as though she was under the influence of a painful nightmare, from which she would presently awake to find herself back again, happily, in her bright, pleasant bedroom at Miss Fenwick’s. The longest journey must have an end, anc length the gig drove into a long, dark avenue, the yew trees on either side of which ere densely thick, and almost met overhead. At the end of this cheerful approach there lay a long, irregular stone build. ing, green and defaced With age and damp. That it was very extensive, and had once been of imposing exterior, Pansy could see; but the appearance of utter desolation and neglect struck a chill to her heart. The blank and curtainless windows, the crumbling window sills, the moss- covered roofs and the hundreds of twit- tering birds that flew, startled, from the dense growth of ivy that hung over the portals, gave an air of ghostlin and unreality to the place impossible ; to describe. Fergus Thunder knocked loudly at ve entrance door, and bidding wait there until it w opened, he took the horse and gig round to the stables himself. “L wonder if they keep any servants,” she thought, listening intently for some sound of life inthe silent house, and shivering with cold and depr sion. “What an age they are answer- ing the door.” She was on the point, at length, of venturing a knock on her own ac- count, when she heard a hevy bolt withdrawn, and the door opened with a harsh, grating sound, as though iv were seldom used as a means of i=- gress or egress. A gaunt woman of about thirty stood on the threshold on the dark in- terior. She carried a candle, and, by its faint, uncertain light, Pansy saw that she was yery pale—pale with the sodden colorlessness that often accom- panies red hair. Her eyes were red- brown, small and closely-set, her fea- tures more unpleasing than absolutely plain. You are my cousin, Phillippa Vere- ker, L suppose?’ she said, offering Pan- sy a cold hand, which she instantly withdrew. blow the candle out.” The girl obeyed, mechanically. So this was one of her cousins! Could it be possible that these pecple really be- longed to a good family? It seemed 1n- credible. “Come!” called the woman, impa- tiently, leading the way down a dark, wainscoted passage, and opening the door of a low-pitehed, uncarpeted room. “This is one of the few habit- able rooms we hav the others are, for the most part, given over to the rats.” She set down the candle upon the table, and made as though she would relieve Pansy of her hat a cloak. “So you are Philippa Vere- ; but the name Philippa sounds nge to me,” said the girl, forcing 2 smile, though her heart died within her at these uncongenial surroundings. ‘They always called me Pansy at sehcol,” “We object to pet names here,” re- turned the woman, abruptly. “You will always be Philippa for the fu- ture. My name is not particularly sweet—Salome, but I prefer not to have it abbreviated to Sally’—with a movement of the muscles of the mouth which did duty for a smile. “You have a sister, have you not?’ ventured Pansy, hoping that the next specimen might be an improvement on thi: you mean Elsie! Yes—at least, not my sister, I am thankful to ince she is very little removed from a natural. No, she is my half- sister.” Here was another cheerful discovery rt “Poor thing!’ murmured Pansy. How old is she?” “Your curiosity seems to be inex- haustible,” cominented Salome. “She will be eighteen in a few months.” She left Pansy to her own reflections at this juncture, and went away, tak- ing the candle with her. When she presently reappeared, she directed Pan- sy to accompany her to the kitchen, where supper was waiting. To partake of refreshment in a kitch- en was, to say the least of it, unstud- ied; but Pansy was too hungry and tired to care for anything. She fol- lowed her guide down one long passage after another, until she came to an ex- ten » apartment about forty feet square, with a brick floor, and a ca- cious fireplace, provided with smoky chimney corners, where a handful of fuel smouldered dully. ‘The room was faintly illumined with an oi! lamp, which swung from the beacon rafters, and hung low over a large deal table, destitute of a cloth, whereon were some rough preparations for a meal. “The kitchen strikes cold, but you'll get used te it by-and-by,”’ observed Sa- lome, motioning Pansy to a seat near the table. “It is the stone floor, which is disposed to be damp; and besides, it is a waste to keep large firés, when you nave little to cook.” Pansy acquiesced, mecherically. She was wondering if it were her fancy, or if someone was seated in the chimney corner most in the shadow. Salome, noticing this, paused in her occupation of cutting bread, to call. gently: “Mordant! Mordart Cain! Are you asleep?” Keceiving no answer, she drew near- er, and called again. “What do you want?’ growled the occupant of the chimney corner, angri ly. “When I don’t answer, it’s because I don’t want to. You’ve no delicacy, Salome, no tact.” Pansy was rather surprised at the vi- olence of the speaker, but Salome was evidently used to it, for she returned to the table with no further comment than that supper was ready. “That is Mr. Cain,” she whispered to Pansy. “He is an old and valued friend of the family, and you must be very civil to him.” Pansy looked as if she did not see the a ruttian, bnt she did not venture to say so, for 2 movement in the direction of the chimney corner warred her that the owner of the rasping voice was coming forth. So strange and uncanny-looking a man as Mordant Cain Pansy had never seen. He was short, but enormously “Come in: the draught will | necessity of being so very civil to such | broad, and as he crossed the room she noticed that he was lame. This deformity must have been caused in early youth, for the foot wearing a clubbed boot was small and wasted, while the other limb was fine- ly-proportioned, His face was strangely pale, and the very sinister expression it wore was ac- centuated by a deep-seated, irredicable sear which crossed the forehead, and grievously marred the features of What must have once been a handsome face. His head was massive, his eyes lurid with a fierce light, and his brows dark and overhanging. He approached the table and seated himself next to Pan- sy. “Well.” be said, abruptly, after he had closely scrutinized her features, “so you are Fergus Thunder’s ward. You're pretty—you need not blush, no good comes of too much beauty-—de- cidedly pretty, but wanting courage, common sense, and most other attrib- utes which go to make up the charac- ter of a useful woman.” Pansy shrugged her shoulders, vouchsafed no reply. ‘The entrance of Fergus at this junc- ture was the signal for the commence- TMent of the meal. . It was the oddest refection with vrhich Pansy had ever been regaled. Four bowls of oat meal were set on the table, and a huge pitcher of milk. ‘This, together with the ruined walls of what had once been a Gloucester cheese, were the sole provisions tor the even- ing meal. “You don’t seem to make much prog- ress With your porridge, Philippa,” said Salome, when, presently, Pansy gave up the bulk of the oat meal in despair. “You will have to accustom yourself to it, as we seldom provide anything else.” “Thank you; I have no doubt I shall get used to it by-and-by. I am not very hungry,” said the girl, covertly watching her guardian, who devoured his portion with avidity, and occasion- ally exchanged a remark, sotto voce with Mordant, between whom there seemed to exi good understanding. “Where is Elsie?’ inquired the latter, with his accustoined abruptness. “When I saw her last she was war- dering about the kitchen garden with Rover,” said Salome, indifferently. “She can have her supper when she comes in; it don’t matter.” “But L say it does matter,” said Mor- dant, angrily. “It is not to our inter- est to have that half-daft child left to herself so much. She will get talking, you short-sighted creature, you—” “I fail to see to whom she can talk, since we are a mile and a half from any habitation,” returned Salome, cast- ing a warning glance at her fathe “Besides, what signifies her tongue? There is nothing to talk about here that would interest anyone.” “Well, Mordant, let the child be—let her be,” said Fergus, who transferred the glance he had received from his daughter to Mordant Cain, who, in turn, looked at Pansy searchirgly. “Would you like to go to your reom, Philippa?’ said Salome. “If so, light one of those candies and follow me.” They went away together, the men talking over the dying embers. It was barely half-past nine, but Pansy thought anything would be better than remaining a moment longer than was necessary in such uncongenial society. She followed Salome up the broad, handsome oak staircase, and thought how different the stately old place would have looked had it been well kept and filled with light-hearted ten- ants. She almost fancied she could hear the ripple of laughter and hum of many blithe voices, but it only resolved itself into the soughing of the March wind, that wailed round and rattled the crazy casements; and yet—yet, surely that was a_ wild, unearthly luugh she heard! “Why are you pausing?’ exclaimed Salome, impatiently, peering into the gloom for her companion. “What is itz “L[ heard someone laughing ,I think— a strange sort of laugh, too. It sound- ed more like a shriek. There—there it is again!” She clasped her hands round Sa- lome’s arm and looked into her f: with startled eyes. Salome wa pale, or looked so by the candle’ ly light. She frowned and shook off the girl's clinging hands, impatiently. “Nonsense! You are absurdly fanci- ful. You will hear many strange noises in an old house like this, where every door creaks and the wind rattles every casement. Heard a laugh, did you? It would, indeed, be strange to hear anyone laughing here, for we are by no means heertully-disposed tam- ily, as you will tind when you know us better. Here is your room,” she said, halting at the end of a long passage, and throwing open a door. “It is not a fanciful bower, such as you have doubtless been accustomed to, but no good comes of too much luxury. | will leave you the light, but you must not burn it long, as it will have to last you a week.” and CHAPTER Hl. Pansy, left to her own reflections, proceeded to inspect her new quarters by the uncertain light of the candle. The rcom was large, and the windews, three in number, were so high up that she could barely see out, even when standing on tiptoe. The room was partially covered with a faded carpet, and here and there were old-fashioned articles of furniture that had evidently once been hand- somely upholstered, but were now but a harbor for moth and dust. The bed, dingy and canopied, struck Fansy as particularly uninviting. She pulled back the old silken coverlet, and shrinkingly inspected the yellow bed- linen. This had once «been costly enough, for it was of the finest quality, and even now trimmed with tattered lace. “Oh, dear, oh, dear!” sighed the girl, miserably, “1 don’t think I can sleep in this bed. I believe it is infester with ghosts. I've a good mind to ring the bell, and tell that Salome that I'm frightened to sleep here alone. And yet, suppose she offered to sleep with me herself? No, no, that is not to be ! thought of.” She began to undress quickly, keep- ing her back towards the dreary four- poster, lest her courage should fail her, and had just unpacked her night dress from the small traveling bag she had | carried, when the door opened softly, and someone glided in. Pansy was too much astonished to | call out or remonstrate at this uncere-_ monious Visit. leaving | “Hush!” whispered the girl who had entered. ‘Pray do not call out, or they will know I am here!” She seemed so terrified, and cast so many agonized glances at the closed door, that Pansy forgot ber owr. fears at the other's distress. “I’m not going to call out; only your coming in so silently startled me,” she said, gently. “Are you my cousin El- sie?” Yes, yes. Don’t speak so loud. Whisper, or they will find I am with you, and they never allow me to talk | to anyone—and I am so Icnely.” She drew nearer to F ook sa at her searchingly. ragile and v delicate! tena girl, w ith a small, f. face, that would have been pretty had it been less painfully pinched and col- orless. Her hair hung in elf-locks of lustreless brown about her shoulders. Her dress was badly made and of the t material. sy stooped and kissed her kindly. “IT am very glad to find I shall have a companion so nearly my own age. It will not be half so dull as I feared. We must be good friends.” “Ah! no. You don’t understand. We cannot be friends openly, They will never allow me to have a companion, for fear I might tell something!” xclaimed, with a wild look in her eyes which seemed bred of a haunting fea “I know very little—nothing, indeed, of their business; but this is a dread- ful house—a dreadful prison, as you will find.” She crept closer to s and caught her by the aria. “Put out the light, or Salome will see it under the door. I have shot the bolt, so she cannot come in. If you will go to bed, | 1 will lie outside on the coverlet, and we can talk, but only in whispers. To say the truth, Pansy was rot very sorry to have a companion; so she ex- tinguished the light, as desired, and got into bed, with a shudder of irre- | Pressible repugnance. Klsie extended herself outside, but not without listen- ing, breathlessly, for any sounds in the house, “They think that I am safely in my own little room. Salome always locks me in every night, and I used to fear being left alone so much that I founa a way of getting out of the window on to the sill which runs along from ore window to another. From thence | can get into the house, for none of the fastenings are secure. Salome never troubles about me until morning,” she said, shuddering as though with nd- den terrible thought. “I think she would leave me locked up if the house were on fire. They all wish I was dead—l! know they do!” y don’t say such terrible a urged Pan horrified at se strange revelations. “Why are you so frightened of them all? You have been brought up here, haye2’t you?” “Yes, yes. Ah! such a weary life!” wailed the girl, pressing her cheek against the hand Pansy had extended to her. “How often I have longed to die since [ was a child! In time—in time I will tell you more—all I know, came home with father, though you did nét see me, ard | liked and trusted your face. Yes, I will tell you some things that will make you fear the dark as much as 1 do. Hush! How horribly the wind shrieks.” She clutched at Pansy den terror. “Promise me you will never let them know I have been talking tou you, or L shall never get another opportunity. They believe me to be half-witted; it is not their fault that I am not, for tney have done their best to drive me mad. I never talk rationally to them, lest they should set a closer watch on my movements, for they seem to be aid of every word 1 utter in the sence of strangers.” She paused to listen intently, and Pansy noticed that even the s¢ of mice behind the wainscot caused her to start violently. She felt in- stinctively drawn to this friendiess girl, aithcugh her wild and exciting Gisclos- ur were r from rea Tell me,” she whispered, mother dead?” Yes, so they tell me,” said the ¥ mournfully. “She went to Italy for her bealth when I was a child and died away from home. It is said that the death of my uncle, her twin-brother, caused her last illne Ah, it makes me shudder when I speak of that!” “Was she, then ,so attached to him?” asked Pansy, stroking the girl's thin hand reassuringly. “Yes; but his death was so sudden, so terrible. I can just remember the confusion and horror of it all. He— Husht” ain she raised herself uponher el- bow to listen breathlessly. “He was found dead in the marsh tield—dead, with his head battered ir She smothered a faint cry at this hid- eous recollection. “They brought him home here cov- erect With a shee nd my mother went quite mad. I was very youn: the time, but I can hear her shrieks and upbraidings now. After that evening I never saw her again. My father took her abrad almost directly, and I think I must have been very ill, for I cannot remember anything beyond that dreaa- ful time for years. I think,” she said, dreamily, “that they are partly right. My head is affected—at least, I am oft- en so dazed with loneliness and monot- ony that my memory fails me. Now— now I have talked too long—too much, and the past is growing dim and uncei- tain.” She broke into a passion of quiet weeping that, with all its bitterness, was so subdued, that Pansy’s heart ached to hear her. She ventured one more question: “Who is Mordant Cain? What is the bond between him and your father?” “IL know not; but sometimes | think” sinking her voice to a whisper—“that he is the Evil One. To him I owe much of the misery of my life; though why he should treat me with invaria- ble cruelty I know not. I fear and hate him, but he can quell me with one glance of his evil eyes. My father is | eruel, neglectful, harsh, and Salome is ! cold and implacable; but I do not fear them as I do him.” “I disliked him at first sight.” saia | Pansy. “He would not be bad-look- ing, though, as regards mere features, were it not for thet hideous sear.” “No one knows how he came by that sear,” said the girl, fearfully. “When L recollect him as a child he was with- out it, I am sure of that; but when 1 saw him again, after a lapse of two or three years, he was disfigured as you now see him.” “Flow loag has he lived here?” asked s hand in sud- for 1 saw you this evening when you | Pansy, who felt strangely interested at the girl's recital. “As far back as Tean remember. He sometimes roams about the grounds, but never within my recollection has he been beyond them.” “But you must have had some educa- tion,” said Pau y, “for you speak cor- rectly, and know kow to express your if. “Yes—he, Mordant Cain, used to teach me when L was a child. I think it amused him to tortvre aud oyertask me, for I was perpetually in punish- ment. My lessons were always too many and too difficult for a child twice my age, and I was never a very apt pupil. At last he locked me up for some hours in a terrible room, built in the thickness of the wall. How welll remember that day! I felt ill, stupid, miserable, and could not learn, and he locked me up for hours as punish- ment.” “Brute! Inhuman wretch!” said Pan- dignantly. “And were your fath- er and Salome too neglectful to inter- fere in behalf of a poor, ill-treated child?” “They did not care. so treated befor monstrated. Th I had often been nd they never re time, though, he for- got m nd I grew so awfuily fright- ened of the dark, that I sereamed and clamored to be released until LE became insensible. When I came to I was u own room, and they told me I had been i for weeks. Since then he ne er offered to resume my eduction, for I eculd never afterwa commit any- thing to memory. That is partly why Lam always so vague, so "tterly incon- sequent before them. You must ap- pear to humor my childish flightiness, and never, never let them know that with you 1 can be ratiovat enough. To them I am fantastic—almest idiotic, and in that lies my immunity from much oppression and ervelty.”” Pansy assured her, again and again that she would never, by look or ges- ture seem to be aware that she had an- other side to her sbarecter. To Pansy, this night of revelations wes the strangest she lad ever known. The v nd shrickirg of the wind, the unc $ broke the still- and the wierdly-fan- tastie disclosures of her newly-found conspired together to fill her error and vague misgivings. CHAPTER Iv. “f want a few words with you, Mor- dant, if you will be kind enough to step into the girden,” remarked Fer- Thunder, the day after Pansy’s ar- t Craige eakfast, a served re table was being cle perintendence of lome, by a buxom young country girl, who acted in the capacity of charwoman. “IT am at your ser Mordant, following his friend out into the bright March sunshine. They walked down the path together, crossed the stile and entered the orchard, with- out exchanging “Well,” rem: ‘anty and roughly- just over, and the ved, under the su- answered rgus, when he e from eaves- pu think of the Tom “what do Strikingly like her father, eh?” pretty and stylish,” admitted Mordant, grudging] but, unfortun- no fool. A great deal too wide to suit our purpose. almost think you would have been wiser to have left her at sch ool. ” “The ! that ii your way, alk med Fe’ testily. “Did you not yourself suggest that by bring- ing Ler here to live, we could save the ‘iter part of the five hundred year Nowed, before she comes of your own sugg' Don't excite yourself un- said Mordant, cynically. not complaining; but I still es. am think she may be a trouble to us. You see, With all Miss Sz sv nee, it will be difficult, almost impos ble, to keep a girl of Mi ge trom ing about the place as then, there is that ic. How can we si- poking and pi she kas a mind t wretched child, E lence her?” “Pshaw! She krows nothing, and can, therefore, impart nothing,” saia Fergus, with an evil frown upon his fac Besides, if you order her to held her tongue, she will not dare te disobey. She is frightened to death of you, Mordant.” “It is essential that she should re- main so. Now, Fergus, there is anoth- er matter which has been occupying my thoughts for some time. This girl, Philippa. on attaining her majority, will be an heiress to the tune of some ywundred thousand pound: Fergus looked up at him suddenly, and as their -eyes met,, both men smpiled. “LT see you follow me.” said Mordant, “Well, to be brief, I made up my mind to marry that girl.” “How about her probable disinclina- tion to the arrangement?” asked Fer- gus. “She has plenty of determina- tion, I should judge, from her fa rhe plan is an excellent one, but 4 fle difficult to work cvt.” “I do not anticipate much trouble in the matter,” rejoined Mordant, dri “You leave all to me. When the girl has been at Black Tarn Grange for a few months, the repression and sol- itude will work wouders—she will wel- come, even my attentions as a relief; but, if that fails, I shall find means to mould her to my will.” (To Be Continued.) tri- What She Learned. Mamma—Well, Elsie, what did you learn at school to-day? Elsie (aged six)—Learned to spell. Mamma—Now, what did you learn Lo spell? Klsie—Man. Mamma—And how man? Kisie (promptly)—M-a-an, man. Mamma—Now, how do you spell boy ¢ Elsie (atter a moment’s reflection)— The same way, only in littler letters. Town end Country Journal. Not So Strange as It Scemed. Mrs. Riggs—Isn’t it strange that the life inshrance company should cancel your policy just when it did? Mr. Riggs—Yes, indeed, considering the fact that the agent came to my office the other day, trying to induce me to take out another $5,000. I told him to-wait a few miutes, as I had te step across the street ta look at a folding bed I had bought; but when I came back he was goue—-New York Journal. do you spell