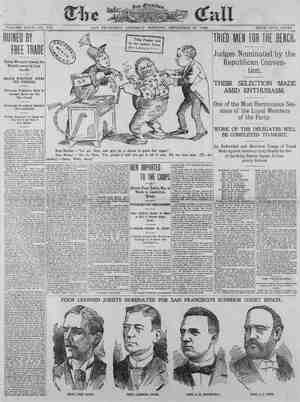

Grand Rapids Herald-Review Newspaper, September 26, 1896, Page 6

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

SS a CHAPTER XVI. he Revolt of the Negroes. When Ernest Hartrey had finished his letter to May, and surrendered it to the care of the Leutenant, who had throughout acted in so fricndly a man- ner towards him, he leaned over the bulwarks and eagerly watched the ship's cutter as she left the Osprey and puiled rapidly towards the home- wardbound vessel. He would have given the world to be on beard that ship, with her head directed tows his native land; and he had ventured to ask Capt. Salt if it were not possible for him to go back in her. , The question roused the irascible na- ture of the captain, who answered fiercely and decidedly in the regative; and Ernest Hartrey had nothing to do but watch the pzcket which contained, among others, his letter to the malt- ster’s daughter, taken on board the frigate. hen the Portswouth-bound ship un- folded her wings of white, the cutter pulled off, and ia an hour's time his wajesty’s ship Osprey was again ding through ze wide Atlantic voyage to the West Indies. The day had been fine, but the sky, towards evening bicame overcast; aud minute, as sunset drew near, inky clouds prew blacker and thicker. The heavens scowled in terrific dark- hess, and tle shadowed sea swelled and heaved until at lenpth the clouds burst in a raging fury of storm and cain. All seemed a mighty conflict. The boisterous gale tore in hideous sound the rugged ocean in wild disorder— hurled, as it were, mountain upon moun , and issued forth loud-roar- ing threats of destruction. The ship, fighting against the fury of the wate was at one moment raised high in on the crest of a wave, the next plunged into a gloomy deep, surroundered by dark and dis- ordered ever-shape-changing moun- tains which towered high above them, vhich there seem@d no pos- sibility of es Then again, in a minute, the good ship Osprey arose again amidst the clouds, and again as suddenly sunk in the dark valleys of liquid hilis. During the storm, the deep rollings of the ship—her deeper lurches—the thundering concussion of heavy seas against her sides—the hollow, dreary sound of the wind howling through her rigging, and the dismal creakings of the masts, bulkheads and other parts of the vessel, were well calculat- ed to strike terror and dismay into the heart of one unaccustomed to the sea. But Ernest Hartr»y was a good sail- or; and though in his yacht he had never experienced such a storm as that which threatened every moment to en- gulf the Osprey in the unfathomable ocean, he had still sufficient experience to understand what should be done, and sufficient strength and activity to help to carry out the orders which ‘apt. Salt shouted through his speak- ing trumpet. For many hours the storm raged with unabated fury, but towards morning the wind moderated; and though it was some time before the sea subsided, when day broke there was no immediate danger to be apprehended. Life on board ship has no very great variety beyond that furnished by the alterations of the weather; and to de- scribe wn detail Ernest Hartrey’s voy- or thither it was bis majes' ship wes ordered—would be tedious in the extreme. Through fair and foul weather they made their way—sometimes with the sea rolling mountains high, at others with scarcely sufficient wind to bulge the sails, and a broad expanse of wa- ter iying about the on every side, with scarcely a ripple, smooth as a mill pond. Seven weeks had passed since Nrnest Hartrey had been rescued from a watery grave, only to become a sea- man on board the Osprey. Tt was a stifling hot afternoon, with the good ship scarcely making any way through a sea almost as calm and mo- as gl. officers and seamen were alike lounging idly about, for there was nothing to do. The decks had been holystoned, the rigging was taut, the sails were set so as to catch every breath of the faint breeze, and all but the helmsman and the look-out were unoccupied. It was too hot and oppressive for any of those rough games in which sailors delight, and which Captain Salt encouraged, as likely to promote the hardihood and courage of his men. It was too hot even for much conversa- tion, and a stillness reigned on board, which was abruptly broken by a shout from the look-out man. “Land, ho!” he er In an instant every one sprang to his feet. Telescopes were put into requisition and eyes were strained into the dis- tance. It required a sailor’s eye to distin- guish the all-delighting coast-line amidst the clouds, and even to Ernest Hartrey a nearer approach of some leagues was necessary before he could discern the land forming amongst the clouds a dark streak above the hori- zon. This streak grew gradually more and more distinct. The nearer the ship approached the more unequal became fits form, till finally it took the shape of land and mountains. It was the northern point of the island of Barbadoes. One of the officers lent Ernest a tele- scope; and as they approached nearer to the shore he was able by its help to discern houses, huts and windmills seattered near the coast; the sugar works and plantations, the foliage and the mountains, doubly precious in his eyes after the length of time which had elapsed since he had seen land. ¥ was almost night when they re ‘d the entrance to the harbor, and the land breeze blowing right in their teeth, they were forced to stand out a little to sea till morning. On the morrow the sun rose in all his glory, gilding the beautiful scenery of Carlisle bay; and before many hours lad passed his majesty’s ship Osprey was safely anchored in the splendid harbor. It was a fine open bay upon which the eyes of Ernest Hartrey rested on the morning of his arrival at the island of Barbadoes. The two peints of land which pro- jected at the end served to make the harbor secure, at the same time that they added matecially to the beauty of the scene. One of these pcints was strongly for- tified, while the other showed to ad- yantage the luxu-ciant vegetation, the mountain cabbage and cocoa-nut tree growing in groves upon it in great profusion. Through the shipping at the end of the bay were to be seen nuntbers of neat cottages, interspersed with vari- ous tropical trees, which afforded the inhabitants the protecting shelter of their umbrageous branches. dn ihe extreme distance the land rose high above the town, and compl%ed to perfection an enchanting land- scape. Verdant fields of sugar, coffee and cotton; fine groves, dark with luxuri- ant foliage; country villas, clusters of negro huts, windmills and sugar works scattered in every direction, and served to remind the heir to the Hart- rey estates, that, though he saw land before him, it was not Wngland, and to recall, with a painful, heartbreaking pang, the many thousand miles of ocean which separated him from his darling May. The good ship Osprey now arrived at her destination, Errest Hartrey sought an interview with Capt. Salt. His anger at his abduction from England had had time to subside in a great measure; but, for all that, he was determined to let his command- ing officer show, now that he could appeal to the civil authorities for sup- port, that he had acted shamefully— not so much in pressing him, for the ship was well under way when his condition in life was made known— but in refusing to allow him to return to England in the ship which bore his letter to May. irnest knocked at the captain's door and was bidden to enter. “Mr. Hartrey,” said the old sailor, extending his hand to him, “I want to talk, with you.” “And I with you, sir. Your authori- ty over me is now at an end, and 1 can speak my mind.” “There you are mistaken. I can place you in irons this minute, but I have no wish to do so.” Ernest Hartrey stamped his foot im- patiently. , Iny lad, don’t be angry about an affair which couldn’t be helped. We were short of hands—terribly short; and every one made a differ- ence, the more especially 4s my orders were to proceed with the utmost speed. “Still, Captain Salt, I do not see—” “Stay—stay! I know all you would say; and as we view the matter in a totally different light, it will be useless for us to discuss it.” “T shall go on shore at once and re- port your conduct.” “Tush! tush! You will do nothing of the kind.” “Pray, why not?” “In the first place, you cannot leave the ship without my permission. In the second ,if you quarrel with me it may be months before you can leave the islaid for England.” “How so?” “Because passenger vessels do not leave every day.” “What do you propose, then?” “That you should return with me in the Osprey.” “Never!” cried Ernest Hartrey. “You cannot suppose I would voluntarily serve as a common sailor?” “Nonsense! Who said you were to serve as a common sailor? I can fill up the vacancies in the ship’s company here, and you shall come back as pas- senger.” Ernest hesitated. “Don’t bear malice. The public ser- vice quired me to make use of you in the hour of need; but now I am pre. pared to atone for any real or fancied indignity. You cannot suppose I was actuated by any ill feeling toward you when I forced you to serve before the mast?” “No, I do not suppose that.” “Well, then, now take my hand in yours and say you will share my cabin with meQome to England.” As he spoke he looked so good na- tured and spoke so cheerily he could hardly refuse. “You will be in England a month sooner than if you waited for the or- dinary passenger boat.” “Thank you—thank you!” said Ernest, the last inducement being too great for him w resist. “I accept your offer in the same spirit which it is made.” “There, that’s settled.” Captain Salt brought a heavy hand down on Ernest’s back, and, with the other shook him warmly by the hand. “I took a liking to you that night of the storm, Hartrey. Your spirit was wonderful?” “I did no more than my duty.” “Of course you didn’t; but that’s just it. When you found it was no use kicking, you settled down quietly in the traces and pulled on with the oth- ers; and I think now you must see the benefit of it.” Ernest smiled somewhat doubtingly. “What I mean is this,” continued ! Captain Salt, “once on board his maj- esty’s ship which I commanded you were bound to Barbadoes, whether you liked it or not; but you had the choice | of going idly and in irons or btsily as a sailor. You chose the latter, and you showed your good sense.” “J hope I shall never have to show it in the same way again.” “Well, for your sake, I hope not, too. ! But now I have no mere time to spare. TH Bj IHNLUUIAHTAVLUUII This day week we leave for England. Go on shore, see as much of the place as you can in seven days, and be on board in time, for 1 wait for nobody.” the opportunity,” said Ernest, leaving the cabin. “Stay! You will want money. Help yourself from that purse and repay me | when you get to England. Get a new rig-out, hire a horse and go up the country. There is much seeing.” With many thanks Ernest ayaued himself of the generous offer, and, in an hour's time, +° or ~» stood on terra firma, wondering greatly at the difference between Captain Salt in nav- bor and Captain Salt at sea. Emest Hartrey had a mind suflicient- ly philosophical to be able to resign himself to circumstances, however un- toward they n same time, it was ever his evdeayor to make the best of them. He knew that for seven da not leave tne under these ¢: he set him- self to work to d st pleas- ant way in which he could pass the week which must elapse before he was again on his way across the ocean. He determined before long m under- taking a journcy into the interior of the country, as Captain Salt had sus- gested, and meeting an Englishman who was already minded to make the journey, they agreed to go together; and, upon the morning following that upon which his majesty’s ship Osprey had anchored in Carlisle bay, the young squire and his new-found friend—a Major Carlington—set forth, accompan- ied by a guide, to visit the interior of the island. To those who are unacquainted with the West Indies it is necessary to ex- plain that every gentleman's house in traveling becomes a hotel, with the pleasant exception that no paymedt has to be made. The hospite y of the West India planters is boundless. Any stranger is welcome for as many days as he may chose to stay, and the best of every- thing is spread before him by the mas- ter, who has ever a kindly word to “Welcome the coming, speed the part- ing guest.” . The scenery through which the trav- elers, passed was beautiful in the ex- treme; but in whatsoever direction they turned their eyes, they saw that hid- eous slavery so long the stain on the fair possessions of England. Black men and women working in the fields, superintended by a white man, lounging hither and thither, but ever carrying in his hand the dreadful, heavy-thonged whip, which ever and anon would fall upon the unprotected backs of the toiling slaves, who dared, neither by word or look, resent the punishment, which but too often was uncalled for. Ernest’s heart sickened within him at this sad sight, and, by his expres- sions of sympathy, won the heart of the negro guide, who was unaccustom- ed to hear kind words from a white man. This negro, whose name was Ja worked up to a pitch of talkativen 5 began to drop sundry da hints, which the young squire unable to interpret, though he gathered from that an outbreak of the negroes on a certain estate not an improbable event, in consequence of the cruelties and hardships to which they had been subjected by their owner. When questioned closely he became silent and no further information was to be obtained from him. The part of the island in which the tourists found themselves as the day drew to a close was vncommonly pic- turesque, comprehending a grand and interesting variety of scenery—com- pining the stupendous irregularity and the dark shades of the Alps with the romantic wildness of the mountains of Wales and Scotland, and a liv va- riety of the soft, undulating landscapes of England. In the distance was a wide view of the encircling ocean, while the for ground was rich in the wild luxuri- ance of tropical vegetation. This lovely scene, illumined by the rays of the setting sun, made the travelers in no way regret the expedi tion they had undertaken, thou sight of a neat and pretty planter’s house, nestling amid umbrageous foli- age, was far from an unpleasant sight to them after their long day’s ride. At the house they were received with the greatest cordiality, and after a pleasant evening, spent principally in recounting th? latest news fron England with which they were ac- quainted, Ernest Hartrey and Major Carlington retired to rest. ‘The next morning they bade a warm adieu to their hospiteble entertainer, from whom they learned something of the character of the man at whose house their next night would be passed. He was a cruel and hard master to his slaves, though civil and courteous to Englishmen; but it was p {1 the hints dropped, that he was a man more feared than liked by all who kuew him. So much did the description given set Ernest against the man who w: to be his host, that, had it been pos ble, he would have altered the pro- posed route to avoid passing a night s he could adoes; and, <0, was impossible, for human habitations were then few and far Barbadoes, and so they proceeded on- ward. The account of thei interesting to themselves, tedious to the general reader. it that, at the end of the second day, journey, though would be who, by his tyrannical behavior, it was said, had more than once roused his slaves to rebellion. It was a low house, built almost en- tirely of wood; and, as they ap- and welcome them. From his reception of them and his subsequent kindly behavior, neither Ernest nor the major would have thought it possible that his character pitable; and left them at night with | after having volunteered to ride witb them next morning some miles upon their way. Poor man! He little foresaw what would happen before that time. He little guessef that never more would he mount a horse—nay, nevermore see the light of day. Ernest Hartrey had been asleep 1 some time, when a wild, piercing “You may be sure I shall not miss | well worth | ht be, while, at the | under his roof; but such an alteration | between in| Suffice | they reached the house of the planter, | proached it they met the owner who, | cigar in mouth, came forward to meet had been correctly described to them. | He was courteous, affable and hos- | | good wishes for their sound repose, ; shout awoke him from his slumber. His room was brilliantly illuminat- ed, but it was not with the golden rays of the early sun, but with the crimson glare of fire! In an instant he sprang from out the bed and looked from the window. The cause was but too apparent. Some of the outbuildings bad been set fire to, and, being of dry wood, | blazed furiously, while gathered around was a concourse of yelling, frantic, half-naked blacks. the dvor of Hrnest’s rsom. He opened it and gave admission to his host ana Majer Carlington, who were both ned with vistols and cutlasses. “What is the meaning of this?” asked the young squire. “The blacks have risen,” answered their entertainer, in an ited tone of voice; “and unless we can devend an hour’s purchase.” Even wuile he spoke the negroes, perceiving that their work of destruc- tion as regarded the outbuildings, was completed, rushed upon the house. ‘Their master, quick as thought. grasped a double-barrelled gun—one of those heavy, 2umbrous things in use before the invention of percussion caps-— and discharged the contents of both barrels at the advancing troop, at the same time calling upon Ernest and the major to follow his example. It was in self-defense; for the b! 5 in their present state, inflamed with fury and rum, were not likely to show mercy to apy white man. “I have barricaded the door,” said the master of the house. “It will take some time to force it. If we can only keep them off a little longer we may escape.” : Again and agaia the guns were dis- charged, and cach time some of the blacks fell ,or retreated, howling dis- mally, although they still mustered a hundred to one. They were terrific odds to fight against, and but small was the chance of the besieged escaping a dreadful Geath. Foiled in their attempts to force an entrance into the house, the furious negroes rushed to the still blazing out- buildings, and, pulling from them fired wood, they hurled it against the house, and piled it, blazing as it was, beneath the verandah. In a very few minutes the wood- work caught fire. A suifocating smoke penetrated to the room in which the three white men were, and the heat became almost insupportable. “It scems a choice of deaths,” said their entertainer; “but anything must be better than stopping here to be roasted alive. Follow me, each with a cutless, and we will try to cut our way through those howling blacks.” It was the only course remaining. As noiselessly as possible they un- barred the door, so as to give their enemies no notice of what they w about to do; and then, brandi their swords, they rushed forth. A shot of batred and derision greeted on, hoping, by the impetuosity of their charge, to force a passage through the revolted negroes. But it was all in vain. re they had gone a hundred yards, a heavy club and a shary knife had robbed the owner of the slaves of his ] and sent him to answer for his misdeeds before the highest tribunal. Ernest Hartrey and Major Carling- ton were surrounded. They stood resolutely back to back, and fought with the courage of desperation. Their powerful arms, and sha~p cutlasses, did great execution, but it was all but useless contending against so great a number, even though they were unarmed. A sudden blow felled the Major to the earth, and then, beset on every side, Ernest was speedily overpowered. A heavy club, wielded by a gigantic negro, was raised high in air, and de- seended with crushing weight, m our here’s head, at which it was aimed, ing him to the ground. For a moment, ng upwards. The next, a hnee was planted on is chest, a sable countenace grinned ly close to his own, jointed knife was clevated to give the death-thrust. Instinctvely, His thoughts, in that one moment of darling May. He thought a prayer removed his he felt the knee suddenly from his chest, the hand from to rise from the ground. CHAPTER XVII. The Black Shadow. For some days after the event of the interrupted marriage, John Gridley and his punishment formed the staple gossip of Annadale. People were not wanting to take the part of tke maltster’s clerk in the r | ter; for his conduct, as faz as the vil- j lage knew, had always been irre- | proachable; and ‘uany declared it to be impossible that »ue so quiet, order- ly and sedate could be tempted to the commission of the dreadful crimes | with which he was charged. | May‘s name, coupled sometimes | with that of Ernest Hartrey, and at | others with that of John Gridley, paged from mouth to mouth; and many were the free comments made upen her behavior by those who, from only possessing a distorted and un- truthful account, believed her to have been in we wrong. | John Gridley, by underhand means, | found a way of fanning the flame. He caused whispered hints which affected | May’s fair name, to be circu ed through Annadale, and at the same time boldly stated circumstances ¢on- | nected with her father’s insolvency. | Net that he himself entered Anna- dale to do so—he knew better than that; but by using his friends as his and enlisting an unprincipled the landlord of the inn, in his », he managed indirectly, to cast . a shadow over the already deeply- shaded life of our poor heroine. Stil, Matthew Rivers had many staunch friends who refused to be- | lievs nd him to show their sympathy; but the maltster was a proud man, and the averted glances of many of the Elverton market caused him inex- pressible pain. But if to a strong, hale man the suf- . fering of unmerited disgrace was so | There came a violeat knocking at | the house, our lives are barely worth | their appearance; but still they rushed | but falling on his shculder, and bear- | he lay helplessly | and aj nest closed his eyes. | agony, flew back to England--to his | for her future welfare. and then—then | throat, and a strong arm helping him | these calumnies, and who flocked | great, what was it to a poor, tweak, tender girl? Formerly, when May walked through Annadale, every cap was raised to her; many eyes sparkled at her ap- proach; the men left their work to speak, if only but a single word, with her; the women gathered round her. So it had been yesterday. Now, faces were turned from her; spiteful tongues whispered cruel slanders, often loud enough for her to overhear; | mothers cautioned thir daughters not ' to mix with her; fathers cautioned | their sons to beware of her blandish- ; ments, and even those who came for- | ward to meet her as usual, spoke as if they were doing a meritorious action in addvessing her, sacrificing their own feelings to do her a kindness. The evil reports spread far and wide as they rolled on, gathering fresh ma- terial and increasing in the way that a few inches of snow, dislodged upon an Alpine peak, mey become an ava- lanche huge enough to sweep a pine forest to the ground. It was not long before the erpressed opinion was that John Gridley had had a very lucky escape. The accusations brought against him were forgotten— , the rumors which he had d to be circulated respecting May were so much more interesting to the | gossips, that his crimes were obliterat- ed by the imaginary ones attributed to her whom he had hoped to call his wife. Where John Gridley went, no one knew. That day he left Annadale he turned upon: the brow of the hill to shake his fist menacingly and vow vengeance, but whither he went was a mystery. He had not been seen in Alverton— he had not been seen in Annadale | since. | Mrs. Rivers suffered severely from the trials and unpleasantness to which | her husband and daughter were con- | tinually exposed. She said but little; | but she grew more feeble, scarcely ever | leaving the house ,but sitting for hours |at a time watching 1 ut her spin- ; ning wheel, with an expression of deep compassion, not unmixed with anxiety, on her once-handsome face. | It seemed as if a deep, black shadow had settled permanently on the cottage | in Annadale which the Rivers’ inhabit- je d,and that the sun never more would | lighten it. All its inmates went about with a | heavy care weighing down their h and a smile on any of their faces w: |as rare an occurrence row as it had | formerly been frequent. | The months passed slowly by, and Matthew Rivers still struggled against misfortune; but the business which had | formerly been so profitable now barely ts expens and though the ~ man fought bravely to main- is credit, it was a hard fight, and y day became more and more doubtful in its results. ba < months since ™ vs’ word had been good as e, at the w et days | | | | | | + » z g § ® ES e 3 but now— |now, many of his former friends turned | their backs upon him, and his de: | Which had formerly been so large, g' | weekly less and less. Insolvency stared him in the face, put through no fault of his own. A conded, and the ye to meet his ew | before been accustomed to; and, iimally, |he had to sell the cob which for so | many years had carried him so well. | It was a pitiful sight to see that old man, bowed down by misfortune, s ting out to walk to Alverton, 5 without recog ion, on the road by | many whose fortunes he had helped to | make. The crushed, white-! ded wearily on h iors and his inf | in their market ce | vily past him on th Si He was down, and no one lent him a helping hand. On bis return he would sink into his | arni-chair, exhausted wike in body an spirit, and hardly speak a word dv ing the entire evening. How d ired man plod- while 5 hed by otted iner- as this from the jovial man who for. merly would come back to s home with a light heart and a n to retail the new. he brough | yerton, and perbaps produce fror ecapacious pockets some little tr | for his pretty useful present for bis staid but happy | wife- Things were, indeed, strangely a tered since then; but even yet Mat filled to the brim. As winter gave place to spring, and ; the trees, before a genial sun, pu forth their first brilliant buds, Mes, | Rivers grew weakev and weaker, and the doctor who called in pro- nounced her suffering from heart d ease, which sudden excitement might end fatally at any moment. It was another blow to the maltster, who loved his wife fondly and well. Turn which way he would, nothing but misfortune stared him in the fac and though he still struggled on, it was as a bowed-down, crushed and hopeless man. He had returned one afternoon from Alvertor. more disturbed even than i—for events had occurred that day connected with his business which threatened to bring down upon him that ruin which for many months had been suspended over his head. For an hour he sat, silent and de- pressed, returning only monysyllabic answers to the questions of his wife and daughter. “We shall have to leave Annadale,” he said slowly, and with a feeble voice filled with emotion. “Leave Annadale?” echoed his wife. “Yes—forever!” Mrs. Matthews only sighed. She knew time was not far distant when she must leave the world and those in it she loved so well; but she litile thought how near that time was at hand. | “Oh, father!” said May, “must we | leave the cottage?” | “Yes, dear, yes.” | “And for ere?” | | “Beaven knows, my child! I old nan, and feel older than my ye: but for your | aust begin life anew.” ‘Oh, has it, indeed, cone to that? What shall we d>?’ “Shall we go to Alverton, father?’ | “No, no! Farther than that—fartLer | than that'” “To Portsinout?” thew Lives’ cup of bitterness was not | ke ard your mother’s i | “Maybe, dear—Portsmouth or Leéns don.” “But what will ycu do, father, when you leave this place? How can you begin life afresh at your age, and with- out money? Cannot I do anything to help you?’ “Nothing, my child—nothing. I can think of no plans—I can arrange noth- ing. I can only hope that heayen may send me help and congort. h, it is hard to feel ruin and disgrace prising on me- But it is not my fault.*Oh, what have I done that these trials should come upon me now, in my old age, when I have not the energy or strength to tight them as I could lave done forty years agg?” “Hush, father! Do not complain of the trials providence has sent for some inscrutable reason.” a] “You are right, May,” said the old man, rising and endeavoring to speak cheerfully, “you are right; and we must all put our shoulders to the wheel and do the best we can. He approached his wife and looked tenderly in her face as the dusk of twilight spread its shadows across the room. “Come, Sus: you and I were made one for better for worse, for richer for poorer—now comes the worse and the poorer; but you will bear up bravely, I know, and help me to meet the trials.” She did not answer, but remained in the same attitude, her head supported by one hand, the other hanging by her side. “We must leave Annadale, and begin life again; but with you and May by my side to comfort and cheer me I will not despair.” s he concluded he took her hand in his; but the next moment, with a gasp- ing sob of terror, let it drop. It fell heavy and Hfeless by her side. It was icy cold—the pulse had ceased to be The imalster’s wife was dead. Calmly and peacefully she had pass- ed away, making no sign to those around her . May threw herself at her mother’s feet, and taking the cold, ssive hand in hers covered it with k 5 “Oh, mother, mother!” she cried; “eome back to us; come back to us!” “No,” said Matthew Rivers softly, “it is for the best! She has gone to a better world; and if the Almighty ever allows the spirits of the dead to re- visit earth and those they loved we may gather consolation from the belief that her dear spirit, though invisible, will ever hovering near us—maybe, guiding us in the way we should go, or whispering words of love and com- fort in our ears. Seek not to recall her to a life of sorrow. It was wisely and well ordained.” May burst into a flood of tears, cry- ing as if her heart must break; and Matthew Rivers stood with dry eyes, but with a feeling which was agony in his heart despite his calm words, and which was almost more than he could bear. | \d For some months the Rivers family. | had been all in all to each other; for they had no sympathizing friends—no kind advisers. True, when the news of Mrs. Rivers’ awfully sudden death was known in Annadale there were some who came and offered their services. They meant well by so doing; but Matthew was soured and was growing daily more gloomy and misanthropic. He courte- ously but firmly refused all aid from his neighbors’ hands. h, how the wind wailed round the moaning and lamenting in A son with the father and his ch}d! v the trees shook their branches ateningly about the cottage! clouds gathered loweringly an ly, as if forbidding him to hope’ The closed shutters, the dismal weather, her father’s grief, coupled ith her own, and, above all, the con- iousness of that which lay so sti! in upper room, bearing the outward rm of her mother, but which would ore speak words of love to her, made poor May ecp about the house as if dreading to hear the sound of her own footsteps. Two men, whose trade was death, ved from Alyerton, clad in sombre and trod noiselessly on the floor room where the body lay; and nt shuddering and starting at sound, however faint, which is- s chamber of death. Matthew Rivers seemed like one in a dream. For hours he would sit rance-like, staring into vacancy; and denly arousing himself by an ort, would try to talk naturally, al- most cheerfully, of his plans for the future. But ere anything could be done, his late wife must be placed un- the fo never, never f the preceding that fixed for the ‘oke dull, heavy and threat- g; and altho! 1 it was yet early an oppressive heat seemed to ise from the earth. Father and daughter sat down to their morning meal in silence, neither daring to speak; for there was a | solemnity which hung about the house which spread itself over the inhabit- ants. It was yet early when a loud and au- \ | thoritative knock sounded against the ter door. opened it and gave ingress to two sturdy-looking men, clad in riding dress, who, without question, entered the room. “Matthew Rivers?” ingly. “That is my name,” answered the malster. a ‘The man laid one hand on his shoul- er. “I arrest you, in the king’s name, at the suit of John Gridley, for a debt of twelve hundred pounds!” (To be continued.) said one inquir- Little Girl’s Wenderful Nerve. A wonderful exhibition of nerve and coolness in the face of deadly peril was shown by Jennie Sheets, aged eight years, recently, near Kagisas City. A heavily-loaded passenge? Frain left Cabool, Me. A small tyestle ter- muinates a sharp curve a few miles east of the town, and the train was making forty miles an hour when the curve was reached. As the train ap- ploached the trestle the engineer Cai two women and twe little girls on the trestle. ‘To stop was impossible. he women jumped to the dry bed of the creek below; the children remained on the trestle. Jennie Sheets was one, “A and she seized her companion, threw her ou the extreme edge of the bridge sleeper and there held her until the train had passed. The train was stop- ped, and the passengers ran back, to tind little Jennie anxiously inquir- ing if her mother was hurt. Ho y