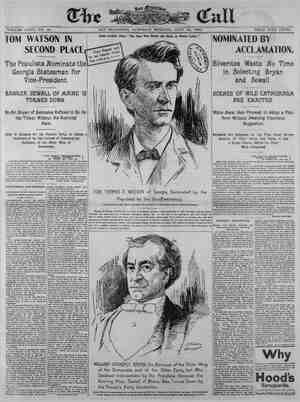

Grand Rapids Herald-Review Newspaper, July 25, 1896, Page 6

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

CHAPTER XXI. Philbrick Surprised. Dr. Williams was toc amazed at the audacity 5 Prof. Drummond’s pro- posal to think for a moment of its offensiveness. “The man’s mad!” he exclaimed. The doctor was not far from right. Whichever way Prof. Drummond turned he saw possible danger. Worse, or at least more terrifying than the dangers he could see were those that threatened indefinitely. The doctor might at any time take it into his head to disclose what he knew; and Philbrick—there was no telling what he knew or inferred or meant to do. Desperation was steadily and rapidly undermining the prof23sor’s mental balance. His violent fits of temper, his inability to conceal his passion at all times, were plain sym toms of the overstrain to which everts subjected him. The proposal for Mrs. Williams was a frenzied attempt, like “You Infernal Young Idtvt.” a last resort, to so establish relation- ships that Dr. Williams, at least, would be bound to silence. “Of course,” said Mrs. Williams, quietly; “it seems like it. I can’t think that he feels any affection for me.” “I should say not! What did you tell him?” “Why, I made it as clear as I could that such a thing was out of the auestion. He begged me not to decide hastily, but to hold the matter open. He promised not to refer to it again until a reasonable time had elapsed. He has said nothing about it since I returned here.” “Shouldn’t think he would. How monstrous it seems!” “He pleaded for Louise and Amelia more than for himself. They needed an elder woman’s companionship, be said.” “Undoubtedly he was right there.” ‘The doctor went to the bedside and gazed at his patient with tronbdled eyes. ‘The horror of the general situa- tion grew upon him as he saw tle pallid face of this innocent girl whose iife had been blasted by the villainy of the man under whose roof she was obliged to find shelter. Was it weak- ness on his part that restrained him still from exposing the professor? What was to be gained thereby? t tre undoing of murder; not the re- st-ration of Amelia’s happiness; not a thing that would be of ben to ainself or his mother. What evil would then be atteudant upon an ex- posure, granting that the crime of @arder could be fastened upen the professor ¢ In answer to this query, the doctor felt a host of ills rising before ¢ the disgrace that so far he had ward- ed from Louise; he shock to his teotecr, Who wou'd suffer he cu ila not tel bow keenly at thought of her assocatcp with t ian; discredit to biuseif. though ibat weighed seast in the balance. And yet, was it not his duty so to act that other crimes might be pre- vented? He had hardly thought of it in this light before, and he shuddered as he recalled how quick the professor was to give way to violent passion. ‘What might not happen if he were permitted to pursue his wretched course? This thought came upon the doctor with the force of a new resolution. He felt himself called on, not only to save Amelia, but to checkmate the profes- sor as well. His mind seized upon this idea with vigor, and he rapidly de- bated plans of action. He had thus far disdained to exert or develop the power he possessed over the professor, except in the matter of compelling the proper care of Amelia. It now seemed to him as if he must establish that power more firmly if for no other rea- son, that in the possible event of a trial he might have incontrovertible evidence against Prof. Drummond. “Mother,” he said, suddenly wheel- ing about, “if it were to right a great wrong could you descend to trick a villain?” “Why, Mason,” she responded slow- ly, “I hardly know what you mean.” “Of course you wouldn't,” he ex- claimed, striding across the room, with his hands behind him; “you wouldn’t understand, for you don’t know what is in my mind, and I am ashamed that I even dreamed of suggesting it. I will handle the matter myself.” Mrs. Williams went to him and laid ther hands upon his shoulders. “My poor boy,” she said, “you are very much disturbed, I know, and I wish I could help you. You feel that Prof. Drummond is a very wicked man, do you not?” “Wicked ist’t strong enough, moth- er.” “It is dreadful that we should have been brought in contact with him so,” she murmured more to herself than to him: “I am thinking of you, Mason, not of myself. What is the great wrong? It isn’t to. either of us, I’m sure.” She looked appealingly at him. “It is to her,” he answered huskily, 4erking his head in the direction of the d. Mrs. Williams pressed her hands gently upon his shoulders. ‘ “What can I do, Mason?”.she asked. “Nothing,” he replied abruptly. ll see the professor.” He started to leave the room. “Are you going to mention his propo- Professor’s Secret. “Very well,” said Mrs. Williams after a moment. “I have confidence in you, but I hope you won’t provoke him. It seems to me he would be dan- gerous if enraged.” The doctor smiled grimly. If his mother had known, as he did, to what excess of rage the professor was sub- ject she would hardly have let him go so readily. “Prof. Drummond does not dare trouble me,” he said confidently; “but I do not intend to provoke him.” In the hall near Amelia’s door the doctor saw Betsey Hubbard gliding slowly along. “A fit inmate of the professor's house,” he reflected. “She moves about as silently and apparently as aimlessly as a cat. What can she be up to? Why does she stay here after her place has been taken? Or why does Mrs. Apple- ton stay? He stopped under the impulse to speak to Betsey, and she looked over her shoulder as if she, too, wished to say something; but as he hesitated she glided on. “T’ll have to think up something in order to lead her into a conversation,” thought the doctor. “For the present I require all the craft and dissimula- tion ¥ can muster with the professor.” At the foot of the stairs he heard Philbrick’s light-hearted tones from the direction of the dining room. A low rippele of laughter assured him that Louise was, as usual, giving the visitor admiring audience. A low rum- ble of bass from the room across the hall testified to the professor’s where- abouts. The doctor knocked at the door, and an instant later the profes- sor opened it. “Ah, doctor,” he said, with an ap- proach of his ordinary blandness, “something wanted for the patient?” “No, thanks,” replied the doctor. i wanted a word with you on a matter not directly connected with the pa- tient. If you are engaged, Vl wait.” Greatly surprised at the doctor’s agreeable manners—for since Amelia’s illness the young man had been curt to the point of insult—Prof. Drum- mond looked across to the dining room. He, too, heard Philbrick’s voice, and, after a slight hesitation, said “Come in here. I am alone.” “T thought I heard—” began the doc- tor. “I was discussing domestic details with Mrs. Appleton,” remarked the professor in a rather loud voice. “She went out by the other door when you knocked.” The doctor entered the room and Prof. Drummond closed the door. “after what has passed, professor,” said the doctor, unsteadily, finding it more difficult than he had supposed to play a part, “it is rather hard to begin a conversation with you on even terms. I have used very harsh language— “Don’t mention it, my dear boy; heat of passion, you know; very natural. I err myself in the same way.” “I am glad you feel that no apolo- gies are called for on either side. I have come, however, not to speak for myself, but for my mother.” “your mother?” exclaimed the pro- fessor, nervously. Really—-” “She has told me of your posal——” “You infernal young idiot! What do you mean?” The professor’s capacity for rage was great, as the doctor already knew, put he was unprepared for the sud- denness with which it burst forth now. As usual, of late, the professor made a strong effort to control himself, with the result that he shook so that the room seemed to vibrate. Dr.“ Williams was completely taken back. “She tells me you proposed mar- riage,” he retorted, after a little pause of astonishment. Prof. Drummond’s mouth was open to speak, but only an inarticulate rat- tle sounded there. Another voice spoke, however, with sufficient clear- ness and emphasis. Conincident with the words a tall screen standing before the fireplace fell down, and there stood Mrs. Ap- pleton, with eyes ablaze and cheeks aflame. pro- Stood Mrs, Appleton. ‘tae professor turned upon her furi- ously>, “Eavesdropping, eh?’ he _ snarled, and raised his arm threateningly. Dr. Williams was thrown complete- ly off his chosen track by this. Diplo- macy, craft, dissimulation vanished into air. He caught the professors arm. “I wouldn’t,” he said, indignantly. “If you must abuse somebody, take a man for once.” “He wouldn’t strike me,” muttered Mrs. Appleton, defiantly, but her voice shook with excitement or fear never- theless. The professor, with his arm still raised and held by the doctor, looked from one to the other, as if frenzied. He brought his arm to his side with such force that even at that tense moment it occurred to the doctor how feeble he would be.in an encounter with this man. “Leave the room,” he commanded, harshly, to the woman. With bowed head and faltering limbs she obeyed. When she had gone the professor sank into a chair and covered his face with his hands. Dr. Willlams wos all at sea. He re- gretted that he had tried to effect anything by craft. “So your mother spoke to you about it.” stammered the professor, present- ly, without looking up. -“It was very natural, and so was your action, but it was terribly unfortunate that that woman overheard you. You see, she’s a relative of mine, with an interést in my property, and that interest would be affected by my marriage. She exacted half a promise from me once that I wouldn’t marry again, and talked about being-a mother to my daughter and all that, but you can see, of course, that she’s wholly un- fitted for such a place. I wouldn't have her in the house now but that Betsey’s departure some time ago made it necessary to have somebody about.” “Your daughter seemed to greet Mrs. Appleton as a stranger,” remark- ed the doctor, who was convinced that Prof. Drummond was lying. “Yes, they never met before Mrs. Appleton came to Fairview. You see is was my plan, if your mother con- sidered my offer favorably, to have the marriage take place without Mrs. Appleton’s knowledge. I wanted to avoid just such sceLes as you witness- ed a moment ago.” The doctor made ro comment. “You were saying about your moth- er,” resumed the professor tentatively. “T think,” resperded the doctor, with- out disguising his ecntempt, “that 1 won’t continue the Giscussion.” “Some other time, then,” said the professor. “Possibly, but let us understand that I am to speak for my mother. If you have anything to say, address yourself to me.” “Agreed, my dear boy, agreed. Pray don’t let my little exhibitions of tem- per disturb you. My bark is worse than my bite.” ‘ Dr. Williams hurried from the room with a consciousress of ignominious failure. The dramatic contretemps he neither regretted por considered. it was sufficient that he felt wholly un- equal to the task of artfully winning some confidences from the professor. “How differently that smooth Phil- brick would save managed!’ he thought. The “smooth” Philbrick was certain- ly having an easy time of it in the course he had chosen to follow. Lou- ise, with her ready faculty of disre- garding disagreeable things, was bright and talkative when with him, and never withheld her companionship. A hundred times he seemed to be on the point of pronouncing the magic words “I love you,” and as many times he drew back, just avoiding them and keeping her heart in a constant flutter of expectancy. She had teased him about himself, and he had told her many a yarn from his experiences, never defining his position in the world with absolute definiteness, but giving her to understand that he was a man of means, that he traveled much, and lived where and as long as his fancy suited. That morning when the professor’s voice was heard in angry altercation with Dr. Williams and the other phy- sicians, she had expressed alarm, and a wish that her father could avoid such distressing scenes. Philbrick had said he guessed he could stop it and had gone through the window. She had not seen what he did, or heard what he said, but she observed the ré- sult, and it filled her with wonder ap- proaching awe. What Wonder, she re- flected, that a man who exercised so strong a control over her father, should have completely mastered her own spirit? Prof. Drummond remained where the doctor left him for several min- utes, and then sought Mrs. Appleton, with whom he conversed at length. After that he went out to the piazza and paced back and forth its entire length. A glance in at the dining room window showed Philbrick in his cus- tomary attitude of leaning slightly to- ward Louise, as if every breath she drew were a precious message to him. “What does he know? What does he know?” rang repeatedly in the pro- fessor’s thoughts. He wished that he had managed bet- ter with the doctor. “If Mrs. Williams will even consider the proposition,” he reflected, “that end of the situation may be covered. Then there’s Philbrick, and Louise will fix him. I’m ony holding back with her anyway for the sake of securing the doctor. What’s the use? The doc- tor seems to be out with her and all chances must be taken on that side with his mother, and the fact that he is publicly committed to an opinion that ought to settle the matter. Phil- brick it is, then.” When he came to this conclusion he was standing in the front door looking toward the dining room. Philbrick and Louise came out at that moment. The time seemed opportune for a stroke, and the professor tried to play it. Mrs. Williams was at the head of the stairs, but he didn’t see her until he had be- gun to speak, and then it was too late to back out, even if he had cared to. “Philbrick,” said he, with ponderous jocoseness, “in my day a young man never carried on his sparking so long without bringing matters to a head.” “Why, papa!’ exclaimed Louise, blushing and feeling extremely uncom- fortable. Philbrick looked down at the ground, his face working and twitching. It would have been hard to say just what emotion was trying to find expression there. “Well, professor,” he began, trying to assume his customary ease, “your daughter and I may yet understand one another, eh, Louise?” He took her hand, and in spite of her embarrassment she nestled close to him. “Amasa!” came in a shocked voice from the piazza just Sass of the pro- fessor. The latter turned about quickly. A tall young woman stood there staring at Philbrick with amazed eyes. Philbrick dropped Louise’s hand as if it were red-hot iron. His face was a study, a mixture of surprise, discom- fiture and huge embarrassment. “Well, well, Mary!” he said, stepping forward with outstretched arms, “how did you come here?’ Then, as she drew back a little, Phil- brick turned to the professor and said in his most nonchalent manner. “Prof. Drummond, allow me to pre- sent my wife.” re CHAPTER XXII Amelia's Awakening. When a man’s wife suddenly appears oe os in a comedy and catches him in the { act of what might be called aggressive flirtation there are two ways of bring- | ing the scene to a conclusion. The au- thor either makes his wife incredibly gullible and an easy prey, therefore, to her smart husband’s ingenious, if pos- sible, explanations, or, in despair of working out the situation logically and naturally, he writes “curtain,” and the spectators are left to supply the sequel according to their several fancies. Often enough it happens in real life that the chief actor in a domestic drama longs for a quick curtain, or, as it is more commonly expressed, “that the earth would open and swallow him up,” but the curtain never falls and the earth never opens. It might have been expected, per- haps, that the genial, entertaining Mr. Philbrick would be equal to the very awkward emergency with which he Nar” “I Am Miss Drummond.” was confronted, but there are limits to every man’s possibilities, and Phil- brick had come to his. Whatever his game might be, it was up, beyond the power of anybody to save it, and he was the first to recognize it. There was nothing for him but retreat. Havy- ing delivered, so to speak, his brazen introduction of his wife, he turned to her, his lips forced into his smile of assurance, with the words: “Shall we return to the hotel, my dear?” “Not so fast,” she retorted, and made as if she would address Prof. Drum- mond, but Louise interposed. “Mr. Philbrick,” she said, going for- ward with extended hand, “had not warned us of your coming and has for- gotten to introduce me. I am Miss Drummond. Your husband is a great friend of ours, and I am charmed to meet you.” All three looked et Louise in amaze- ment. Her face was highly flushed and her voice was a bit unsteady, but otherwise she seemed to be perfectly composed. She was so eagerly insist- ent in presenting her welcoming hand upon Mrs. Philbrick that that lady was forced to take it, and having grasped it she held it while she looked into Louise’s eyes and said: “Tell me the truth, Miss Drummond! Nothing is to be gained by playing a part with me, though you begin won- derfully. I have only sympathy for you. My husband never told you of my existence.” Her glance was keen and searching, and Louise quailed before it. The part she had assumed was too much for her. Tears showed in her eyes, the flush on her cheeks gave way to palor and she turned to Philbrick. “Where is your assurance?” she cried bitterly, “that you compel me to suffer this?” s Louise found herself addressing Philbrick’s back. When she had gone to his wife and attempted an impossi- ple smoothing over of the situation he had shrugged his shoulders and faced away, as a silent acknowledgment of his utter defeat. Prof. Drummond, meantime, had been standing as if paralyzed by the unexpected disclosure. His lips were parted and his hand half upraised. Anger raged within, but found no ex- pression because his fear was greater. What ought he to do? He knew that he ought to feel and express indigna- tion for the imposture practiced by Philbrick, but he dared say nothing lest he arouse the man to active hostil- ity, and his feelings were more con- cerned with his own safety than with sympathy for Louise. Had it been pos- sible for the professor to learn that there was a Mrs. Philbrick in exist- ence he might have held the threat of exposure over Philbrick’s head; but there she was, the exposure was made and all hold upon a possible enemy was lost. Louise’s prompt attempt to save her pride gave the professor a cue to which he tried to speak. “There is evidently some misunder- standing here,” he said feebly; “if there was any fault in the matter it was mine, I assure you, Mrs. Philbrick. I yielded to an impulse for fun, and was just playing a practical joke on your husband, whom I regard very highly as a friend.” “It was a cruel joke to me, papa,” said Louise, tremulously; “you see what a false position you’ve placed me in.” These were valiant efforts to bring about peace, and while Prof. Drum- mond for the first time in his life felt a positive admiration for his daughter, Philbrick felt perhaps for the first time, a sense of shame. He turned slowly around, and, without any trace of his characteristic confidence, said: “I am exceedingly sorry, Miss Drum- mond, that I had a share in the practi- cal joke. I might have stopped it—” “No, no,” interrupted the professor, seeing his vantage clearly now; “it was all my fault. It was bad taste on my part, and the end would have had no fun in it. Provided only we under- stand each other now, and proceed without acrimony, I shall be very glad that Mrs. Philbrick came in upon us as she did. Won’t you come in, madam, and make yourself as much at home as your husband does?” “There!” thought the professor, “if he doesn’t feel grateful to me for get- ting him out of a scrape, I’m mista- ” Mrs. Philbrick had dropped Louise’s hand, and now stood looking from one to another in embarrassment an doubt. ‘ “J arrived in Belmont about an hour ago,” she said slowly, as if talking to herself, “and went to the hotel. Mr. Philbrick was not in, and I hearned that probably I would find hima here. So % came down without the least thought of making a scene. I think we'd hetter go to the hotel, Amasa.” “Certainly, my dear,” responded Mr. Philbrick humbly. “Let me get the carriage and drive ' you down,” exclaimed the professor. “Thank you; no,” returned Mrs. Phil- brick firmly, “I much prefer to walk.” “I'l not urge it, then, but won’t you sit down and rest?” “I am not. tired. The business I came to see my husband about is press- ing, and I must speak to him.” The professor was very urgent with his hospitality. He was congratulating himself that the device attempted by Louise was succeeding under his hands. Could he but succeed in pre- venting a domestic break in the Phil- brick partnership he would have one danger fairly disposed of. “T should be only too glad,” he said, with his usual blandness, “to have you take possession of my parlor. You shall be wholly undisturbed for as lit- tle or as long as you choose to remain there, and later we will have lunch. What do you say, Mrs: Philbrick?” There was an expression of haughty displeasure in her face. She glanced doubtfully at Louise, as if wondering just how far that young lady was sin- cere, and replied: “J must Cecline. Come, Amasa.” “Then you'll come up in the after- noon or evening. I shall look for you, Philbrick. We will want to get ac- quainted with your wife.” “I shall not remain in Belmont,” re- marked Mrs. Philbrick, stiffly. Philbrick went to the hall rack for hig hat, while his wife stepped out to the piazza. Louise remained in the hall, holding herself well in control, but expressing contemptuous resent- ment in the glance with which she fol- followed Philbrick’s movements. “Iam hors du combat, you see,” he whispered, with a grimace, as he passed the professor. “You'll come along all right,” re- joined Prof. Drummond, in a low voice, and he gave Philbrick a playful pat on the shoulder. “Good day, Miss Drummond,” mum- bled Philbrick, as he passed her. She did not reply, and when Mr. and Mrs. Philbrick started down the steps she turned to go up stairs. “You do magnificently, my dear,” ex- claimed her father, his eyes glowing with appreciation. Louise stopped an instant, gave him a glance of withering contempt, and then hurried over to her room, where she locked herself in tnd gsve way to tears of mortification. Wher Mrs. Wiilinms saw that a “scene” was impending she was more than half way down stairs. Instinct- ively she retreated, but the real mean- ing of the situation was revealed be- fore she had come to the top. Se sur- prised was she, that but for an in- stant she steod still, and so heard a rert of ihe conversation that followed Philbrick’s introduction of his wife. Then, as the mischief was done, the professor had seen her again, and she cculd not be regarded as an interleper, she remained listening until the end, after which, with amazement and trepidation at the unceasing complica- tions in Fairview’s affairs,she returned to the sick room, just avoiding being seen by Louise. The docter saw at once that something had happened, ond asked about it. “As if there wasn’t already enough to perplex one.” she responded. “Well, but what is it, mother?” “Mrs. Philbrick.” “Mrs. —-—. What? Philbrick mar- ried?” The doctor himself was so aston- ished that he sat staring, open- mouthed, while his mother briefly re- counted what she had heard. “What a villain he is!” he exclaimed, and he went to the window, forgetting for the moment that it gave him the Miniski, and not upon the road to Bel- mont. “Who's a villain?” asked his mother. “Who? Both of them! Poor Lou ise?” He left the room abruptly. Curiosi- ty had its place in his make-up, as it has in that of all of us, and he wanted the satisfaction of seeing Mrs. Vhil- brick with his own eyes. He heard the professor pacing heavily in the broad hall, and, unwilling to have any words with him then, he went to a window over the piazza and looked up the road. It didn’t seem, at a distance, as if a serious cloud had come upon their re- lations, and the doctor wondered whether Philbrick had succeeded, with his customary assurance, in hoodwink- ing his wife. They were walking close together, and Philbrick seemed to be indulging in one of his extravagant fits of laughter, iu which his wife appar- ently joined. “Extraordinary man!’ muttered the doctor. When he returned to the sick room his mother said: “J think she’s waking up.” The doctor hastened to the bedside, and his mother left the room to com- plete the errand that had been inter- rupted by tbe advent of Mrs. Phil- brick. Amelia’s eyes were open, and she was lovking up to the ceiling. Her express- ion was clear, but a little wondering, withal. The doctcr felt his heart beat- ing strangely as he saw that she had returned to consciousness. He held his breath as she roused from ber rey- ery and turned her eyes to nis. A faint flush overspread her eheeks as she rec- egnized him. “Dr, Williams? ’she said, with glad surprise ringing in her faint tones. “How Do You Feel, Asked. Amelia?” He Impulsively she thrust one pallid” hand from beneath the coverlet, and as he took it and pressed it gently be- tween his own, the color upon her face brightened. “How do you feel, Amelia?’ he asked, in a choking voice. “So strange!” she answered, with a smile that belied her words. For an instant her >yes closed, and when she opened them again the doctor felt a slight but unmistakable pressure from her hand. In that moment those two read one another's souls; ibe seerats’ of their hearts were laid too plainly’ be- re them to need words of avowal. } aha yet there was hesitation and there : was so much that each one conscien- tiously thought needed explanation y pr em the first to feel the diffi- a dence that ever stands as a bar to the t complete expression of love, but en she tried to withdraw her haw the doctor resisted. She smiled again, @ = happy smile, end turned away her | suppose I’ve been awake only 2 ; | minute or two,” she said, “but so much has gone through my mind in that wy time! . How long have I been sick?” “Two or three days,” replied the doc- tor. “Don’t let that distress you. You are going to get well.” \ “Yes; I know I am. I feel it, and—I } am very glad. I wouldn’t have sup- posed I could feel glad again.” Dr. Williams remembered that he was the physician and bent his nead, i} not trusting the man to speak, but his whole being thrilled with a joy that 5 would have found words a sorry vehi- ele. He would have liked to sing, but, to keep strictly within the bounds of truth, the doctor’s singing, while it might have been highly satisfactory to | himself, would have seemed sorrier than words to listeners. 4 “Of course, when I awoke,” con- tinued Amelia, “I couldn’t think at first what had happened, but I saw that I was in my own room. I remembered leaving it intending never to return. e Then I was conscious that I had beep a ] here for it seemed a long, long tim and I thought, somehow, tnat you hat been here, too. So I wasn’t surprised exactly when I saw you—though—” She paused a moment and added with an effort: ‘Though it seemed t very natural, and I was happy.” ‘ “You mustn’t talk any more now, } dear,” whispered the doctor, hardly - able to form his words. “Remember, #&? I am your physician, and I must see to it that you do not overdo.” “How good you are! But I wanted you to understand that when I said I felt strange it was because I couldn’t quite understand how I could feel any way but hopelessly melancholy. And yet it is so natural, too?” She sighed lightly and closed her eyes. The doctor released her hand at last j and stood up. The realization of his ae | surpassing interest in this patient was » now full upon him. He had fought off truth during her long hours of uncon- sciousness and had told himself that his watchfulness and anxiety were dic- tated by impulses of common human- ity mingled with resentful determina- tion to prevent Prof. Drummond from accomplishing any further wickedness. He had admitted to himself no more than a longing, not altogether vague, that he sternly tried to regard as a weakness and to suppress, and if Ame- lia had awakened with her tortured mind still directed to the unhappy 5 past, with no outlook but misery and 4 no thought of him, perhaps he would have suppressed it. Some men can measurably control their affections, but yw if the doctor was one of them, Ame- lia’s awakening dissipated all thought and desire of banishing from his life that which was sweetest. The physician standing by the bed Began to Mix the Contents in a Mortar. F and gazing down at his patient, still feared to excite her in this incipient _ conyalesence; the man bent over an > pressed his lips to her bro w. Tha * 1 faint flush returned to her cheeks, they °/ lips parted in a happy smile, but the eyes remained closed. It might have been too much just then for her to bear the sight of a loving face, but not even the methodical physician could fear that the expression of love would prove to be too strong a tonic. “She is much better, mother,” said the doctor quietly, as his mother re- 4 entered the. room; “she will get well.” Prof. Drummond was vastly disturb- | 4 ed by the scorn his daughter displayed as she swept past him and went up stairs. Into his heart there came some- thing like a reminiscence of human ¥ tenderness, and he remembered that Louise had substantially admitted to him that she loved Philbrick. Intent upon the fears of his own situation he had not contemplated the reality of hopes, aspirations and emotions on the part of his daughter. He felt dimly and resentfully that there were other persons in the world besides himself, other interests than his own, and his selfishness rebelled while his distorted pereeptions began to take on new sus- picions and new fears. Perspiration é was on his brow, indicative of the agony in his mind. He strode up and down the broad x hall several minutes trying to get hig thoughts in order, and at last went tog” his “shop” and locked himself in. om did not busy himself with mechanic appliances, but took several bottl from a closet and began to mix the contents of some of them in a mortar. (Lo be continued.) Wanted His Money's Worth, The robust looking old farmer for the first time traveled on with a dining car. He had read ut the high prices for train meals, when he sat down at the table he dered some bread and butter and a of coffee. The waiter looked at him and whistled softly. After the robust farmer had concluded his slim repast a ticket for $1 was handed him. “Great Scott! Do you charge a dok lar for what little I eat?” he asked. “Yes, sar; $1 is the price of de meal > no. ak roe vee ordah.” & peter somanied Fy ipa Ara aman who w: 3 “well, bill of fare," said the farmer ea he cal Sore oes the Pipers under his w bis