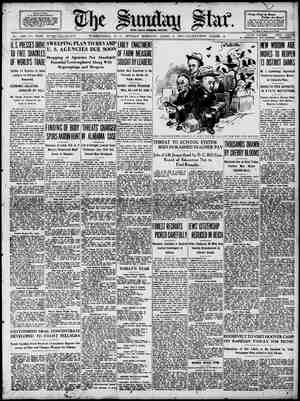

Evening Star Newspaper, April 9, 1933, Page 23

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

THE SUNDAY STAR, WASHINGTON, D. C PASSOVER HOLIDAY SEES SYNAGOGUE BY VICTOR H. BERNSTEIN. ggyptians and delivered ordained by the Lord that Jews might the first Seder, thousands of Jews the progress of Israel in Palestine. And, rael and the synagogue into a real and | Two thousand years ago Jews massed | everywhere use the Sabbath to awaken of the Levites rose above the stir of women—even Gentile voices—blend in Great Neck. Long Island, dedicated its | zt’:nsner. many club rooms. In common money on educational and recreational | Cleveland, the Sharai Zadeck congre- others, rival universities and “Y” in- There are Jewish voices that rise in and banjo almost in the shadow of the beneath the same roof that echoes the able from those of the Gentiles. Some “graven images” of clay under the see a sacrifice of the spiritual to the manufacture of a toothsome coating for But the modern, university-bred critics. - He- rests his case on the ne- ot only a center for wotship, but the mo more than “meeting place.” He schule, or school. And if he is so minded | of assembly and house of study—the | the circus”; that gymnasiums, ball| enough, that the ecstatic dance of upon the entire problem of ‘“non-re- complete assimilationist, is a place not Local conditions, the character of the | recreational equipment will lead toward | | renaissance, a movement to reattain | born almost with the times that called the first decades of the nineteenth cen- that they had been forgotten in every- {of synagogues built in his time have RENAISSANCE! Innovations and Ritualistic Changes Seek to Recapture Dominance Over Jewish Life. ) Reform synagogue in 1838, conducting | services therein along lines laid out by German leaders of the movement. Reforms spread, in grqater or lesser degree, through the demands made by similar Reform societies throughout the | country. Thus were established the congregations Har Sinai in Baltimore, Emanu-El in New York, Keneseth Is- rael in Philadelphia, Sinai in Chicago | congregations of today. . A medieval Jew, transposed to this age through some cabalistic necro- |mancy, would find much that was | strange and puzzling, but probably even |more that was familiar and understand- able in the synagogue of today. .He | would feel most at home, of course, in | some of the older European centers of Jewish worship. He might even recog- nize some of them. The synagogue of Worms, built in the eleventh century, and the famous Altneu Synagogue in Prague, built a century or two later, are the oldest in the world. The history of the latter is dlmost a counterpart of the history of the Jewish race. Catastrophe has hovered over it a hundred times during the dark centuries. Fire has licked at its walls, floods of the River Moldau have of pillage and destruction left by howling mobs, have ended miraculously at its very doors. Within, the blood of martyred worshipers has been spilled on floor and walls. Yet it stands in- tact, and our medieval Jew would find nothing about it that was strange ex- cept, perhaps, that the street on which | it faces has risen, and one now enters the synagogue by descending steps into a cellar. The synagogue at Amsterdam, though not built until the latter half of the seventeenth century, would also seem familiar to our venerable visitor. Time has changed it little, either out- wardly or in the rituals which take place before its holy Ark. In contrast to these old houses of worship, to which tradition and legend cling like vines, are the synagogues in Russia. The largest and most beauti- ful among them have been despoiled, and the majority have been turned to civic uses. In other parts of Europe, too, our medieval Jew would find that hundreds been destroyed through fire, pillage or the wantonness of hostile mobs. He would find that other synagogues have been metamorphosed into churches by papal edict. The Synagogue of Toledo, built in the fourteenth century, exists today as the Church de Nuestra Senora de San Benita and in Seville an old synagogue is now the Church of St. |and many other of the leading Reform | eaten greedily of its foundations, paths | {0 BY GOVE HAMBIDGE. SIDE from the President him- self, two men bear the brunt A 1ift American agriculture out of depression—Henry A. Wallace, the new Secretary of Agriculture, and Henry Morgenthau, jr. Mr. Morgen- thau will be known as the governor of the farm credit administration as a re- sult of President Roosevelt’s order of two weeks ago abolishing the Farm Board and providing for a merger of |the Federal farm loan agencies into a | single organization. | ‘Though the work of Mr. Wallace and | Mr. Morgenthau must of necessity be | co-ordinated, each will cover a dis- tinct field. As the line-up looks in its present stages, Mr. Wallace will deal with that | controversial aspect of the farm prob- lem known as farm relief—the means by which the farmer's purchasing power | can be brought up at least to its pre-| war level. Mr. Morgenthau will handle | the less controversial but not less im- | portant business of administering farm | credits. | Let me qualify that last statement.| Any one who watched tho recent bat- | tle against mortgage foreclosures in the | Middle West would hardly say that farm credit is a matter beyond con- | troversy, Mr. Morgenthau’s job will be | t it beyond controversy—to make | credit for agriculture so flexible, simple | and adequate that it will not be a cause of bitterness and contention. Mr. Wal- | lace, on the other hand, must deal with questions which, short of the millen- nium, probably never will be beyond controversy, even though a compromise is agreed on for a given program. Father Envoy to Turkey. A tall, rather thin man, this Henry | Morgenthau, jr, with a long face, a | high bald forehead, gray eyes, specta- cles; not a man of marked mannerisms or rugged exterior; rather, in appear- ance, the scholar, the professional man, quiet, intelligent, firm, capable, .g-i proachable. =Forty-two years old, he| was born within a block of his present | home across the way from the Museum. of Natural History, almost in the mid- dle of New York City. His father was President Wilson’s Ambassador to Tur- key—an authority on the Near East, an eminent lawyer, a man with liberal social views, founder of the Bronx House Settlement. Morgenthau, jr., did not follow in his father’s legal and ambassadorial footsteps. Social work he was inter- ested in—for a time he served with Miss Lillian D. Wald in the Henry Street Settlement and in the Bronx House. But there was a queer quirk in him; even as & youngster his inclination was away from the city, countryward. Back in Germany his ancestors had been Baralome. Were our Jew given wings to follow from the air the dispersion of his co- religionists over the face of the earth he would probably receive his greatest shock from the boldness with which his brethren had built their shrines in the great cities. In his day synagogues | were built in the ghetto, in the darkest and most malodorous part of the com- munity, in a narrow, crooked street that the sunshine could not enter, and the Gentile, unless on destruction bent, would not. Variety of Architecture. Though he might be impressed by the size of some of the synagogues, our Jew would not be surprised at the' variety of their architecture. Jewish farmers. Perhaps there was some old buried urge that made him think of 1 as the best of all. pursuits. With the choice of any profession or any school open to him, he chose to go to_Cornell and study agriculture. It might be noted here that the same sort of thing cropped out in his sister, Mrs. Helen Fox. She is an enthusiastic and skillful gardener, with more than one garden book to her credit—the lat- est an alluring book on raising and using the old-fashioned herbs on which our grandmothers set store. Built & Thriving Farm. When young Morgenthau’s health broke down he made a bee line for a Texas ranch, where he stayed until he builders have always been strongly in-|got well; but the farm bug only du fluenced by the country in which they | Geeper under his skin, ke & Texas were building, partly because they did | chigger. He set out on a pilgrimage to ;;n vlvnm"theihx; ;or{uw stand. ogut th see what farms were like here, there ominently ostile eyes. r Jew | and everywhere, with a view to gettin would hardly be able to distinguish the | himself snugly set on one of ‘them, The famous Five Synagogues of Rome from | upshot of it was that the Hudson Valley the secular buildings about; in Je-|looked about as good as anywhere, and rusalem he would see domed syna-|there was New York at the door for a gogues with mosque-like minarets. He ! market. He bought three old farms would recognize the Romanesque syn- | back of Fishkill Hook, 1400 acres in uBsoguen;t Worms and the Gothic and| a)), rich bottom land, almost every field yzantine synagogue at Prague. At | watered with spring or brook. It was on Nagasaki, in Japan, the synagogue|s mud road, and in spring the holes would appear almost as a pagoda. He would see in Newport, R. I, and in Charleston, S. C., synagogues in char- acteristic Colonial or Georgian style. Even in the newer synagogues, in the ‘!))uflding of which noml'estraint has een necessary, no distinctive pattern has been followed. s It is true that were this pious Jew to drift to earth somewhere in these United- States, or even in a few places elsewhere, he would refuse to enter some synagogues that at a distance would seem to be welcome refuges for his weary spirit. He might, as did Chief Rabbi Cook of Palestine a few years ago, refuse to enter a Conserva- tive synagogue in Montreal because its ark, contrary to Talmudic regulation, was not built at the east wall—the wall nearest Jerusalem. He might con- sider it profane beyond redress that the rabbi should lead a prayer with his back to the ark. Certainly he would | consider it sinful that no mechitza, or separation by curtain or grille of the women from the men in the congrega- tion, was present in the synagogue. Yet were he adventurous enough to: stifle his first aversions and continue on, he would recognize much and in his way understand much more of what was about him. He would gaze vith knowing eyes at familiar decora- tions about the ark and hangings— the interlacing triangles, the Lion of Judah, the flower and fruit forms. There are only a few emblems, char- acteristically Jewish, which may be used to give an air of devotion to a synagogue, and our venerable visitor has seen them all in his own day. Our Jew, wandering out of the syna- gogue proper, might think of the club rooms and school rooms and libraries as so many Beth Ha'madrashim, or E passed over the houses of € the children of Israel in vpt, when he smote the our houses.” Thus the Old Testament relates the origin of the Passover, a celebration not forget His power and their deliv- erance from bondage. But tomorrow evening, when the holiday begins with world over will remember other things also: the plight of Israel in Germany and Eastern Europe, perhaps, or the assuredly, many will call to mind the comparatively recent birth of a move- ment destined, it is hoped, to bring Is- abiding reunion. | History, too- lazy to be original, is | rewriting an old chapter in Jewish life. in the synagogue at Tiberias to spend | @ Sabbath declaiming against the des- potism of Rome: today foremost rabbis their congregations to the despotism or chicanery of politiclans. Two thousand years ago “the singing and the playing the vast multitudes in the court of the Temple”; today music has returned to the synagogue and voices of men and trained chorus with the sound of the | organ. | Recently Beth El congregation of | new synagogue, a beautiful Gothic structure. It has a completely equip- d gymnasium, a swimming pool, a with hundreds of other synagogues and temples throughout the country, its congregation spends more time and activities than on performance of re- ligious ritual. The Brooklyn Jewish Center, the Temple on the Heights in gation in Detroit, the West Side Jewish Center in New York City, the Reform congregation in Chicago, among many stitutions in the completeness and wariety of their physical equipment. Some Protests Made. protest at this state of affairs. The ultra-orthodox ®see profanity in the swaying of Jewish youth to saxophone holy ark of the covenant. They look with horror upon bared heads at wor- ship, upon women smoking in club houses chant of prayer, upon prayer books shortened and so twisted, in their eyes @s to make them almost undistinguish- among them may even lament over children who, almost within sight of the tablets that expressly forbid it, fashion guidance of art teachers. In this apparent dwarfing of purely religious to secular activities the cynical commercial spirit, a bowing down to mammon and the great god advertising, an interest less in religion than in the it. The people will not go to religion, they say, so religion is coming to the people—and leaving God behind. rabbi, who can discourse with equal felicity on Talmud, technocracy or ‘Tammany Hall, has an answer to these cessity for reintegrating religion and life. He points out that the earliest history of the synagogue reveals it as «center of Jewish culture and social life as well. He recalls that the very word - e” Greek in origin, means points out that the age-old tradition of the synagogue has been such that in ‘German and Yiddish it is called he will quote Talmud to show that of | the three historical functions of the bynagogue—as house of prayer, house Jast is agreed upon as the holiest. He will admit that in certain in- itances the “side shows have swallowed rooms and swimming pools have tended to obliterate the spiritual significance of the synagogue. He sees, readily David before the Ark in the Temple at Jerusalem is a different thing from the jazz steps of today. But he looks ligious” activities as one of administra- tion rather than principle. The syna- gogue, in the eyes of every Jew but the only where Jews may foregather, but where their Jewishness should be in- creased religiously and culturally. congregation, and above 2ll the spiritual strength of the congregation’s leader- ship, will determine whether elaborate | that goal. Synagogue in Renalssance. The synagogue then is in a kind of the dominance over Jewish life once held by the synagogues of ancient and medieval times. The renaissance was forth its need. The fury for liberty, equality, fraternity, let loose by the French Revolution swept Europe during tury, and in the sweeping leveled ghetto walls that had stood four centuries or more. Rights so long lost to them thing but prayer, were now granted the Jews—the rights to citizenship, the choice of occupation, to live where they houses of study. He would not be so far wrong, either, for more and more is Hebrew being taught in synagogue schools, while increasing stress is be- would, to mingle with Christians in the | ing laid on Jewish history and Jewish schools and in the world of business. It was natural that this new freedom should press upon the old loyalties and the old traditions of many Jews. The ‘New World made insistent demands upon the time ordinarily devoted to the Sab- bath. Superstitions and legends, nur- tured in ghettos where the passing of time was marked only by the greater or lesser hostility of the world outside, could no longer survive the breeziness of the world’s market places. The sense of unity, heretofore enforced by out- ward pressure, Was now to some extent Joosened, and the communal life of the ghetto synagogue was no longer suf- ficient for the thousands of liberated Jews. In Berlin and elsewhere there was growing up a generation that had be- gun to ignore the synagogue alts gether, while their elders were giving no more than lip service to the ritual and prayers. In an attempt to revita- lize the religion for the new generation qtopics in general at the forums and | meetings of various kinds that make up the cultural life of the synagogue. Appropriately enough, our Jew would find himself most at home, so far as | the United States is coneerned, in this country’s oldest congregation—Shearith Israel, on Central Park West in New York City. Here architecture and serv- | ices alike would strike many familiar chords, for since its founding in 1655 this Spanish-Portuguese community has maintained its ritual practically intact, although it has changed its | building several times. | Certain Reform Synagogues, however, would probably prove too much for even the most liberal minded of medieval Jews. In Rabbi Stephen S. Wise's Free Synagogue in New York City there is not even an ark! What profound men- |tal and spiritual adjustments would |our visitor have to undergo to accept the confirmation of girls and the holding of | Sunday services? Were our visitor from and to make the synagogue an insti- | medieval France, he might not be sur- tution meaningful to a Jew who might | prised to see worshipers with uncovered want to be a German as well as a Jew, | heads, for some of the congregations of the reform movement was born with|the time are sald to have discarded that the founding of the Berlin Reform | Oriental custom, but he would unques- Congregation in 1810. Today this re- | tionably be shocked at the language of form congregation is one of the most |the prayers, at their shortness and at radical in the world. In common with | the deletion from the ritual of some ot only two or three congregations else- | them of all references to a future in Je- where, it has departed so far from rusalem. traditional Judaism that it holds its| But these digressions our patriarch services exclusively on Sunday. might learn to forgive did he know that, The Reform movement spread | despite them or because of them, his throughout Europe, but only lightly.|descendants are growing in stature as The Liberal Congregation in London | Jews, feeding gladly upon the culture alone can compare in liberality with |and the religion that has given to clvili- the Berlin institution. For the rest,|zation those twin nobilities, monotheism the many that are called liberal in|and the conception of the brotherhood | Germany, in France. in England, in|of men. It is this spiritual appreciation Ttaly, here would be called conservative. |of Judaism that the leaders of Jewry ‘Their reforms have been more of the | today are seeking to spread. Once upon lJetter than of the spirit. a time the synegogue and life—Jewish It remained for the United States, |life—were one. The modern world, with her tolerance and her adventurous | catching up with the Jew in the early #pirit, to nurture the Reform movement | nineteenth century, tended to break into full maturity. The Reform Society | down this union. Will the unity be re- of Tsraclites of Charleston, §. C, was stored now that the mods spirit 15 stablished in 1824 and built the first |catching up with the synagogue? went all the way through to China. rHe spent a couple of years filling them up with all the picturesque old stone fences. Today the place is a thriving farm— yes, it throve even in the black year 1932. Two farms, rather—one devoted to fruit, one to dairying. There are some 250 acres in apple orchards, one- half now in bearing, mostly McIntosh; | a few peaches. In 1932 the apple crop | was 23,000 bushels—fine fruit, well grown, well handled, sold in New York for the best the market would fetch. ‘With pardonable pride Mr. Morgen- thau says: “The cold figures on our income tax return show that we made & sizable profit, even last year. Not only on fruit, which is my end of the game along with my Yankee manager, Jim Bailey, but on the dairy, which I let out on shares to Arthur Hoose. We have 100 head, registered Holsteins and registered Jerseys. Built up the herd slowly, with only a half dozen good cows to start with. Say, I wish you could see that prize Holstein bull of ours —Pishkill Sir May Hengerveld Dekol. A | wonderful animal—he increased the production of his daughters over their dams by 30 per cent—and I haven't heard of anything better than that, not in this State, anyway.” Eleven years ago Mr. Morgenthau bought the American Agriculturist, one of the oldest farm papers in the United States—founded in 1842, in fact. This he publishes in Poughkeepsie, the near- est big town to his farm, and he has built up the circulation from 100,000 to 160,000, almost entirely in the New York milkshed — that cluster of States and parts of States from which rivers of milk flow daily into the metropolis. Roosevelt Watches. Franklin Delano Roosevelt meanwhile had watched the farm, the paper and the man himself with interest. Mr. Morgenthau has not played the political game, but he was immediately drafted to head a non-partisan agricultural ad- visory commission when Mr. Roosevelt became Governor. Two major pieces of | legislation in the interest of rural com- | munities can be chalked up to the credit of that commission. First. they reapportioned State aid for dirt roads. Previously State aid had been given on the basis of the assessed valua- tion of property. Suburban communities nearest the city, with the highest assessed valuation, got the most help. The Morgenthau commission changed that. Today, if the community spends $50 on a dirt road the State matches it with $50—with the result.that poorer | communities get just twice as much help as they had before. The same principle was applied to State aid for rural schools. Secondly, the commission put through | legislation to discontinue county as- sessments for paved highways entirely —hitherto the counties had had to con- tribute 35 per cent of the cost—and to reduce the contribution for the elim- ination of grade crossings from 10 per cent to 1 per cent. In his campaign for re-election Gov. Roosevelt was able to tell the taxpayers of up-State counties esactly what they had been saved to the penny through the vigorous work of the Agricultural | Advisory Committee. One of Mr. Morgenthau's strong in- terests is conversation. During his sec- ond term Gov. Roosevelt put him in charge of the State Conservation De- partment to work out the big re- forestation program for which tax- payers had voted $20,000,000. As every- body knows, reforestation still holds a large part in the Roosevelt creed. Qualifications Listed. Henry Morgenthau, jr., then comes‘ ito his job as governor of the Farm | Credit- Administration with these qual- { ifications: ‘ (1) A practical interest in farming from boyhood strong enough to have molded the course of his life. (2) As good a university training in agricul- | ture as can be obtained. (3) 18 years' of the administration's fight to | HENRY MORGENTHAU, JR.—HIS of experience in farming. (4) 11 years of experience as a farm paper editor, which means close acquaintance with the problems, disappointments, Kicks and achievements of farmers. (5) Four years of experience shaping and putting over legislation for the benefit of rural communities. (6) Close acquaintance with the views and meth- ods of his chief, now President. Some probably will object that he does not represent the agricultural Middle West. Some are bound to point out that he is not a dirt farmer brought up in overalls from boyhood. If he fails at his job these things will be held up against him. they won't cut any ice. ter of fact, they will have nothing to do_with success or failure, eithcr one. Now, what is the program on which he sets out? Up until the time of President Rocse- velt's order, agricultural credit in the United States ctuld hardly be dignified by the name of a system. It was a complicated chaos. This was not any- body’s fault, especially. The whole thing just naturally grew up more or less helter-skelter. The first Morgenthau job is to reduce this chaos to order and simplicity. The second, after the system is organized, is to turn it over, as far as pessible, to the control of the farmers themselves. Varied Credit Given. Aside from financing done by local banks and by insurance companies, the Federal Government has given_several different kinds of credit to farmers, JOB IS TO HELP THE FARMER. ~—Underwood Photo. |large. Add these costs to interest and | the charges became excessive. [ be able to go to a single building and there get any kind of loan to which he | was entitled—a short-term loan for planting or harvesting a crop, a two or three year loan for the purchase of live stcck, a mortgage on his farm, a loan to finance a co-operative market- ing organization. All of these functions, the executive order specifies, will be under a single department, the Farm Credit Adminis- tration, with Henry Morgenthau, jr., at its head. There still will be separate ivisions, each with a distinct function, but in accordance with Rooseveltian principles of administration there will be no boards or alibis. Each division will be headed by one man, who will be fired if he does not make good, and these four division heads will be re- sponsible to one department head. The work of each division will be logically defined so as to do away with overlapping. All local farm credit cffices will be located, as far as possible, under cne roof, and they will be located for the greatest possible convenience in meeting the needs of the different farm- ing regicns. Of the four divicions, cne will carry out the former functions of the Farm Board—financing co-operatives. One will handle all crop loans and direct loans formerly handled by the Depart- ment of Agriculture and the Recon- structicn Finance Corporation; one will handle the mortgages of the Federal Under the plan as recently- ordered | | by President Roosevelt, a farmer would | handled through four different agen- |Farm Loan Banks and the rediscount cies. (1) The Farm Board advanced | functions of the intermediate credit money to co-operative marketing as- | banks, and one will handle the re- sociations. (2) The Department of | financing of existing mortgages and xAgflcuuu:e flmnde L‘ixretcé1 losgsh to | other debts owed by farmers. armers to finance plan and har- yesting. (3 The Reconstruction Fi- T T D nance Corporation granted regional| hat last, for the present moment, credits and also to some extent made | js Jikely to mean more to farmers than direct loans to farmers in competition | aJ] the rest of the credit plan put to- with the Department of Agriculture. | gether. There are those who say that (4) The Treasury Department, through | the farmer does not need ‘relief” in Federal Land Banks and intermediate | the sense of schemes for bringing up credit banks, gave loans on mortgages | the level of prices or reducing the and rediscounted other agricultural | acreage of crops; that the chief thing paper. he needs is to get off his back a load of From the Government’s standpoint | debt contracted when property values all this meant unnecessary overlapping | and all values were very much higher and duplication. . From the farmer's | than they are today. Whether or not it standpoint it meant confusion and | iS true that this is all the farmer needs, costliness. This last was partly be-| it is certainly the most imperative and cause credit agencies were not by any | immediate need for vast numbers of means always conveniently located. | farmers. The farmer sometimes had to travel| Much has been accomplished by hundreds of miles to get his loan, pay | President Roosevelt’s recent order, raflroad fare or buy gasoline, put up | especially in the way of centering re- at a hotel. Few direct farm loans are 'sponsibility; but legislation will be ADVENTURE BY BRUCE BARTON. ANY men who do not admit it publicly have secretly surrendered to the defeatist philosophy. They say to themselves: “We are in the grip of forces too great for us. Nothing can be done except to await the out- It is useless to try.” M come. Contrasted with this I find in many younger men a point of view which is full of hope. They say: “These are thrilling times. We do not know where we are going, nor what will occur. But whatever happens is bound to be exciting. Before us lies a great adventure.” The president of Dartmouth College, Ernest M. Hopkins, reflected that attitude in a fine speech which I heard him deliver at the inauguration of Stanley King as president of Ambherst College. ” ¢ Said Mr. Hopkins: “If I were to pick out one quality that I thought most essential for a college president I think I should start with inconsistency. For such an one thing is so indispensible as the willingness to be open-minded and toler- ant toward new points of view and the willingness to be re- ceptive to those points of view to the extent of changing his own mind if, after due consideration and reflection, his earlier beliefs prove to have been insufficient or inexpedient. . . . “Sir Thomas Browne said three centuries ago that it was too late to be ambitious, that all of the great mutations of the world had taken place. We know how wrong he was, and yet we find in every age and in every time men who believe that it is too late to be ambitious for further service. . . . “In olden times Spain put upon her coins the legend ‘ne plus ultra’—nothing more beyond. And then the mariners of the Mediterranean sailed out by the Pillars of Hercules and explored the great outside waters and the distant shores bounding the seas, and Spain then changed her motto to ‘plus ultra’—more beyond. . . . “Today . ..I would emphasize more particularly than any matter of policy or even than any glory of tradition the statement that Paul makes in regard to Abraham—that when he was called to go out into a place which he should receive for an inheritance, he obeyed and went out, not knowing whither he went.” I make no apology for this long quotation. There is no better mental picture for us to carry with us these days than the picture of Abraham who went out, not knowing whither he went, but sure that an inheritance lay at the end of the Jjourney. All the pioneers, all the explorers gnd leaders and build- ers have gone out not knowing whither they went. Our danger is that because we cannot see where we are going we do not even try to start. It isn’t necessary to know the end. If the whole path ahead were clear, there would be no adventure. e are on our way to something. Something exciting and worth while! b ' (Coprright, 1933.) APRIL 9, 1933—PART TWO. New Chief of Farm Credit Here Is a Study of the Man Who Will Lead the Fight to Restore Agriculture. needed to perfect the plan, and this. is up to Congress. But all this, as was said above, is |only the first part of the farm-credit program. The second part, though not Once a clean-cut, simple credit structure, adequate to meet the needs of agriculture, is set up, or is well on the way, it is the President’s further thought that it should be decentral- ized and made a co-operative imple- ment owned by the farmers them- selves. The system would consist es- sentially of regional co-operative credit organizations, locally controlled and getting somewhat the same kind of supervision from Washington that the Federal Reserve System exercises over member banks. At first the Gov- ernment itself would have to operate the entire system, but as rapidly as | possible control would be turned over to_the communities. i If such a plan were carried out it would nullify any criticism that farm credits were arbitrarily controlled. So much for the farm-credit set-up as it is conceived in these early stages. Mr. Morgenthau's job is not by any means confined to the heady and in- spiring work of helping to formulate and carry out a broad plan like this. There are the devilish and messy de- tails of cleaning up the legacy left by previous efforts to stabilize the market in various farm commodities. Wheat, which is now statistically strong, is probably the least troublesome of the problem. Much more difficult is the matter of more than 2,000,000 bales of cotton on which the Farm Board made loans, and & nice bill for carrying charges coming in inexorably cvery menth. This represents about one-third of the annual consumption of cotton by domestic mills. But in ad- dition, Mr. Morgenthau, as a result of his office, is a coffee merchant on a large scale and under the reorganiza- tion will inherit from the Crop-produc- tion Loan Division of the Department of Agriculture liberal supplies of al- most everything from cotton to canned tomatoes. Of roughly 2,900,000 bushels of bluegrass seed in the United States, the Farm Board had loans out of around 2,300,000 bushels. And so on. Acts as Super-Salesman. How to get out from under this stag- gering inventory is enough to turn an ordinary man into a nervous wreck. Mr. | Morgenthau apparently remains calm, | in chief—and what a job! Mr. Morgen- | thau has been acting as the Govern- ment’s super-salesman himself. One thing he determined to do and that was to liquidate as rapidly as pos- sible. The policy of hanging on is | stantly increasing loss; it means that | existing funds that might be made | available for the legitfmate marketing operations of co-operatives must be used to hang on to stocks that are nothing but a drag on the market. | Getting rid of them -is a painful op- | eration, but it has to be done. Also | Mr. Morgenthau is against keeping se- cret any longer the amounts of va- rious commodities on hand. Unicertainty, |in his view, helps to keep the market | depressed. | “Moreover,” he sald, “once imme- diate commitments are out df the way, Farm Board loans—or what used to be Farm Board loans—will be made only | for the actual marketing business of | co-operatives. Co-operative marketing | reduces costs and makes possible a | greater return for the producer, and this is a legitimate use of Government funds. But public funds cannot be used to aid speculation commodities, whethet on the part of co-operatives | or anything else.” Another change in policies has been the speeding up of loans. “Formerly | the making of a loan was a cumber- some procedure that sometimes took weeks. We have simplified it to the point where we can get a loan lhrou?h within 24 hours of the time the appli- cation for the loan is made. In tl speeding-up process, Dr. W. L. Myers of Cornell, my assistant, and Herbert E. Gaston, who was appointed secre- tary of the Farm Board when I took office, have gladly taken on new and difficult responsibilities.” Which seems to be the spirit in ‘Washington these days. }Railroaded'F;e;lch Law Ties Hands of Police PARIS.—In the excitement of pass- ing the March budget the French Parliament unwittingly passed a con- siderable amount of miscellaneous leg- islation. One new law, when it was promulgated the next day, gave the entire French police organization the shivers. In practical effect, it is a habeas corpus law, a thing France has never had before. Deputy Guernut, head of the “bill of rights” group in the CI ber of Deputies, is responsible for its passage. Heretofore it has been possible to arrest and detain any citizen for an al: most indefinite period, without bail anc without trial. 'These so-called ‘“pre- ventive arrests” were used on a large scale by the police whenever there was a threat of trouble. On the eve of labor mass meetings it was customary to arrest the principal Communist agi- tators and keep them behind the bars until the meeting was over. Under Guernut's law preventive ar- rests are forbidden and magistrates are required to release prisoners on bail except in the case of serious crimes, When deputies learned the nature of the law, after it was passed, they asked the minister of justice to delay pro- mulgation until it could be reconsid- ered. Guernut promptly gave notice that if the minister of justice failed vo promulgate the Jaw_he would move s impeachment. As Guernut is a promi- | nent member of Daladier’s majority in the Chamber he had his way. (Copyright, 1933.) Wales Gets Another Handle to His Name LONDON.—The Prince of Wales has acquired another handle to his name. He has accepted the presidency of the Highland Society of London on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of its founding, and will preside at the annual dinner of the association on June 8. King George is chief of the society, which includes scores of noted Scotsmen. Among the Prince’s many titles are four that definitely link his name with the northern kingdom. As the eldest son of the King he is _the Duke of “PAN-AMERICAN DAY” FINDS' LATINS SURE OF NEW DEAL Next Friday’s Celebrants Envision Opera- tion of Policy of “The Good «Neighbor.” immediate and urgent, is not less im- | | portant 1n the whele picture. BY GASTON NERVAL. HE celebration of “Pan-American | day.” next Friday, seems a most appropriate occasion to dwell upon certain fundamental prin- ciples on which the pan-Amer- ican ideal is founded Of course, to those who still think of pan-Americanism in terms of the Monroe Doctrine and of the “big stick” role advocated by Theodore Rooseveit, the pondering of such principles will be & waste of time. But to those more en lightened students of international a fairs who are beginning to look at thes: things from angles other than those of | sheer physical force or of immediate | profit, in dollars and cents those fund- | amental principles reveal themselves | more clearly every day. Let us begin, however, by stating at | ica—except the Buenos Alres leaders who disliked Bolivar's growing infli- ence—thought of mysterious designs, of evil intentions, of imperialistic ambi- tions hidden behind the name of pan- Americanism. Nobody thought, then, of any of the nations on this continent using the pan-Arierican scheme ftor furthering t own interests to the detriment of those of others. Years 1ii~ however, when the statesmen of the North rescued the pan=- American idea from oblivion and unae:= took to carry it out—though not before having dep-ived it of its contractual, obligatory features—the lack of under- standing of the purposes of the United States resulted in a sentiment of fear and suspicion on the part of the Latin republics. Afraid of Disproportion. the start that - pan-Americanism as| The Latin Americans became afraid practiced today is quite far away from | of the enormous disproportion in po- the goal set by those who gave it to | tential resources and economic strength the world. Pan-Americanism today is between the United States and the still merely a state of mind, a school of | scarcely organized states of Latin origin. thought based on geographic propin- | Such disproportion was more appar- pending the appointment of a liquidator H quity, economic interests and the simi- | larity of governmental institutions | among the nations of the Western Hemisphere. But it confiines itself, merely, to the casual furtherance of social, economic and, very rarely, cul- tural links between the two Americas. It can scarcely, then, be called any more than a movement, a tendency. Ideal of the Pioneers. The ideal of the pioneers of pan Americanism, on the other hand, wen much further than that. They dreame: of a political system in which all the states of the New World wouid be closely bound to each other. A sys- tem in which they would all be polit- ically united, without losing their in- dividuality or their internal sovereignty, and in which all would enjoy equal rights, share the same responsibilities and comply with similar obligations. This, at least, was the pan-Americanism of Simon Bolivar, and since Bolivar no one has spoken so forcefully or so plainly. This is the only kind of pan- Americanism compatible with the ideals of equality voiced by Elihu Root, which have been so often forgotten in the past. This should still be considered the goal of all true, practical, worthwhile pan- Americanism. True enough, the present pan-Amer- and respect for others, | ent and more dangerous in a free as- sociation like the one suggested by Uncle Sam, without a political com- pact, with no rules, no duties and no specified rights, and in which every | one of the Southern republics had to stand by itself beside the “colossus of the North.” They could not understand, more- over, the sudden enthusiasm of the United States for ' pan-Americanism, xcept on the supposition that it velled lesigns on her part for obtain > ‘The War with Mexico had left bitter memories. This misunderstanding was later in- creased by certain mistaken policies of the United States in the Caribbean region, by the distortion and misuse of the Monroe Doctrine, by the glbenul- | istic_attitude followed from Cleveland to Coolidge, by the so-called “dollar | diplomacy” and others which until not long ago were well-known features of | the Latin American policy of the State | Department. In recent years, it is true, much of this suspicion and resentment has dis- appeared, particularly since the Hoover- Stimson policy of non-intervention and | greater respect for the sovereignty of | the smaller Latin American countries came into being, the old legend of jcan tendency may be the path which “Yankee imperialism” has been giving will eventually lead us to such a goal. | way in Latin America to new confi- Let us hope it will. But it is only fair | dence and new hopes. But, of course, to admit that in nearly half a century | there still remains much to be accom- finished. It not only means a con- | | that the creditor could continue to de- it coud have brought us much nearer to it than we are at present. As a mat- ter of fact, whenever this current pan- {fcalappearance, whenever it has ven- tured on political ground, it seems to have taken us farther away from that goal. Refers to Blaine Movement. When I say “the present pan-Ameri- can tendency” I am, of course, referring to the movement started by Blaine— the pan-Americanism of the pan-Amer- ican conferences, of non-committal, diplomatic flirting, of flowery speeches and forgotten ‘“‘recommendations”— which is still the pan-Americanism of 1933. And by “the incursions of this | tendency on political ground” I mean the abuses committed under the Mon- roe Doctrine, the “North American fiat” of Cleveland, the “big stick” of Theodore Roosevelt, the “big brother attitude of Taft, Wilson and Coolidge. It can hardly be denied that these things have hurt-the political prestige of pan-Americanism. But it was so, only because they were improperly cov- ered with the pan-American label. Really the only thing they can prove is that the fault was in letting one { political scope of pan-Americanism and | the rights and duties which this would justify. Under a general and perma- nent organization, under a pan-Amer- ican system of equal obligations ana equal rights, no such misunderstand- ings, and no such misuse of power as i the former gave rise to, would have been possible. Indeed, the very errors committed in the name of pan-Americanism should be the strongest arguments to empha- size the need for a mofe substantial, a more concrete, a truly political pan- American scheme. At this time, when South American peace is being dis turbed by two undeclared international wars, such need is tragically magnified. Coincidence of Good Friday. Pan-American day happens to fall this year on Good , the day set aside by Christendom to mourn the crucifixion of the Lord. It is & sad coincidence, to say the least. Now, what—besides fixed and common aims and this lack of political organization—has been, mainly, in the way of a better under- standing between the two Americas? The mwe‘ri:)wnwned in one single George ‘Washington of the Southern Hemisphere, laid down his plans of continental union, in 1826, no one in Latin Amer- American tendency has taken on a polit- | country alone interpret by itself the. eignty | plished in this respect. The misun- derstandings of three decades cannot be | undone in three years. | Prospects Brighter. |, Yet the prospects for the future, as far as relations between the two Amer- | icas are concerned, seem brighter to- | day. The President of the United | States has just dedicated this Nation to the “policy of the good neighbor— the neighbor who respects himself and because he does so respects the rights of others"—and Latin Americans in- terpret this as a promise that the policy of non-intervention and of friendly co- operation toward them, recently in- | augurated, will be continued. They are | confident of the “new deal” in inter- | American relations. Clearly, the trend of the Latin-Amer- jcan policy of the United States has been, for the past few years, one of de- parture from the wrong policies of the past and of closer and clear a) tion to the idesls set forth Secretary of State Elihu Root in visit to Rio de Janeiro 111906, when he declared: § “We wish for no victorles but those of peace; for no territory eéxcept. our own; for no sovereignty except sover- ‘We deem Bk i e £ : rights or privileges or powers do not freely concede to every ican republic. We wish to prosperity, to expand grow in wealth, in ] 8 1p] ers and profit by all friends to a common this absence of | ests And once they have, who can say that we shall not then be\ready for the real, ultimate, pan-Americanism, of rights and mutual obnnfim—thw- Americanism _ which Simon var dreamed of, while his con armies were creating one South Te- public at the seat of each high Andean peak? (Copyrisht. 1935, | (Continued Prom First Page.) assume that Congress, by one act or another, puts the country’s currency “off the gold basis.” about all these billions of dollars of bonds, mortgages and other contracts containing the old “gold clause.” ‘The universal assumption has been mand and insist on getting gold dol- lars of the old size, weighing 23.22 grains. [Especially has that been as- sumed by the creditors. ‘The question, of course, would go into the courts, ultimately to the Supreme Court. What the Supreme Court would do is a thing about which there can be only surmise. Some similar ques- tions arose during the previous period of controversy about currency, during the 1870s. They were decided in a group of decisions called “the legal tender cases”—those old cases are now being pored over by lawyers every- where. The most important of the old “legal quote WY ports Annotated—*“established "the doc- trine that express provisions for pay- ment in gold were valid and enforce- able, as if they were for payment in wheat or any other valuable thing. * * * In that event, what would be done | Rothesay, and he is also Baron of Ren- TR s e e 21 real 'ward of Scotland. e 8cot- | such contracts.” tish section of his wardrobe at York| 1t should be added, neverthele House is exceedingly extensive, for it|gsome lawyers who have nmg?y“ gu;;: g”&?:fi regimental as well as other|gver the “legal tender” cases hold the cv dress, view that those cases would not, as of (Copyright, 1933.) today, act as a conclusive precedent pre- venting the courts from holding, under present conditions, that a contract con- taining the “gold clause” must be in gold only and cannot he satisfied by ordinary “legal tender”; that is, ordi- nary paper currency, for example. There is, in short, difference of ROME.—The autobiography of Prime | opinion about what the courts would Minister Benito Mussolini has just been | now do, under today's circumstances, published in a Chinese translation, ac- [after a lapse of 64 years, and a great cording to the Roman press, which re- | change in conditions, since Bronson vs. gards the event as another evidence(Rodes. In any event, there is a prob- of Fascism's expanding influence in the | ability, at least, that the courts may Every case decided by the Supreme Court has r the validity of Duce’s Autobiography In Chinese Translation world. The translator is Pel Hsuan, who is described as having translated numer- ous books on. sm. (Copyrisht. 19330 { ::l!:' have occasion to pass on the “gold A recent and extremecly important and interesting case, arose year U. S. Courts May Have to Decide Validity of “Gold Clause” in Loans lawyer in the United States will be look- ing this case up shortly—for a similar case, many similar cases, may arise at any time, in any county court in Illi- nois or Iowa or Kansas or_California. In 1928, in England, a Belgian com- | pany, the “Societe Intercommunate,” | borrowed £500,000. They gave in return bonds. In the bonds was a “gold clause” similar to the American one, stipulaf that the company would pay “in coin of the United Kingdom of or equal to the standard of weight and fineness ‘?’9‘%}“’9' on the first day of September, | Last year, when interest came due,. a holder of a bond demanded gold. In | |the mean time Great Britain, on Bef-‘ tember 20, 1931, had “gone off the gold } | basis,” and the paper pound had be- which was and is $4.86. Gold Held Not Necessary. The debtor pounds, The fused that form of paymens = case went into the British High Court of Justice, Chancery Division. This court handed down its decision on October 27 last. In part, the said that the obligation was to “one hundred pounds” and that if sum were now paid in gold the pay- ment would actually be more hundred pounds. “It is not a contract. * The contract is a sim- Pple contract to secure payment of & sum of money, and if the defendants ten- der the sum in whatever pen to be legal tender at the date payment was due, they have discharged their obligation. * * * In this country there are certain things, paper and metal, which are legal tender, and for lhelgurpono(unnxldebtlm of the appropriate amount of any of those symbols is sufficient to the obligation. * * * This is not a con- tract for the delivery of gold; it is & contract to pay & sum of money.’ This decision was in e in England, xnmgwmom