Evening Star Newspaper, September 7, 1895, Page 14

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

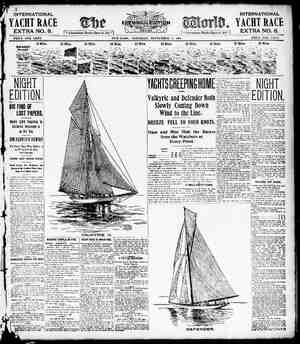

14 ————— THE EVENING STAR, SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 7, 1895-TWENTY PAGES. A MILE A MINUTE Not an Uncommon Railroad Speed in These Days. BOT HIGHER RATES WILL BE REACHED Authorities Are Confident That More Can Be Done. THE ENGLISH LOCOMOTIVE (Copyright by Bacheller, Johnson & Bacheller.) HE RECENT achievements of the 4 I English in the mat- ter of rapid raiiroad running have clearly shown that the limit of speed for passen- ger trains has not yet been reached. It is true that the mile- a-minute runs of the English trunk lines were not regular pe: formances, like those of the empire state express, which travels regularly over the 410 miles of track between New York an Buffalo at a fifty-two-and-one-half-mile rate, but the success of the experiments prove tkat sixty miles an hour is quite practicable, and, being practicable, must, sooner or later, be regularly performed. It is an interesting question, now, whether the first regular performances at this speed are to be on this side the water or in Eng- land, and a not less interesting question has to do with the possibility of regular railroad running at the higher speeds of eighty and one hundred miles an hour. No one in America is better qualified to speak upon the probabilities in these di- rections than H. Walter Webb, third vice president of the New York Central iai- road, who originated the empire state ex- press, and has had more to do with the de- velopment of high railroad specds than any one else in America. M Webb is fully conyinced that the practical limit has not yet been reached “Many persons believe,” sail Mr. Webb a level territory, with thin ballast and light rails, for $10,000 a mile, 1ot counting cost of right of way, deep cuts and heavy fills, and allowing for the usual numder cf bridges of the ordinary type. “It would cost $15,000 a mile more, I shonl@ say, to put such a road into first- class shape for the transit of heavy mod- ern trains, hauled by the big engines of to- day at speeds of from fifty to eighty miles an hour. It is likely that a road thus fitted up could stand an average of sixty miles an hour after certain modifications had been made here and there; but in order to make the higher speeds of eighty and cne hundred miles the road would have to be almost entirely rebuilt. “To average eighty miles an hour, a train would have to make an occasional dash of one hundred, the same as the fifty-mile trains now have to make occasional dashes of eighty. The track would have to be al- most perfectly straight; what few curves there are would have to be of very wide radius, grades would have to be cut down, grade crossings would have to he out of the question, rails would have to be much heavier and bridges would need to 9¢ per- fection. Otherwise it would be impossible to keep the train upon the track at all The Fastest Engines in America. The enormously increased first cost and maintenance, as outlined above, is really the greatest element of additional expense in modern high railroad speed, and cb- viously it could not be undertaken on any line excepting one erijoying a very large traffic. The cost of motive power for very fast service, however, contrary to general belief, is not mifth in excess of the cost of slower engines. This was explained to the writer by Mr. William Buchanan, who su- pervised the building of all the engines that haul the fastest trains. Mr. Buchanan believes that, with all con- ditions as they should be, the big engines now in the fast service between. New York and Buffalo could maintain a cons radly, higher speed than the present aver. and this is based upon the every day re- curring fact that the Empire State Express makes sixty, seventy and eighty miles an hour at certain portions of the run. Only the other day this train, when behind for some reason, covered the distance be a Buffalo and Syracuse—one hundre and forty-nine miles—in as many minutes, cr at a sixty-mile rate, and if It 2an run cne hundred and forty-nine miles at that rate, it can run any other distance at the same speed, providing the tracks are straight, level and clear. In fact, it is provable, though Mr. Buchanan did not say the engines now hauling the Emp’ Express could average seventy or eighty miles an hour. Number %) has move than once reached one hundred miles an hour on short stretches, and on one occasion, in 189%, ran for a short distance at one hun- dred and twelve and a haif miles, which is far and away the greatest sp2ed ever ob- tained by any motor, ither steam or elec- tric. There is no doubt that the best Amer- ican engines are fully the equals of the best English ones as regards speed, and, as is generally understood by railroad men on both sides of the water, there is no com the other day, ‘that the chief factor in the mainte of high speed is the locomo- tive. Now, while it is true that high rates cannot he made without first-class motive power, it is also true that ‘high class en- gines must have high ciass roads to run and that without these it would h mpossible regularly to maintain even miles an hour economically. In fac! the great tasks of railroad ms pr to run trains at high first,the creation and then the m. of an adequat made as light z ptened, gra upon sulting ec such 9s tr that on the as and mai spead of and there t more rapil ru tively common a f A Readbed for Speedy Running. Undoubtedly, then, the chief engineer and his supperters, the roadmasters, the bridg builders, and all who haye to do with the “physical condition” of a railroad, are to form a more important factor in the fu- | say iM ture, even, than in the past in the admin- | istration of the up-to-date railread line. As a matter of course, therefore, the chi engineers of all the big roads are con- | stantly scheming end planning to straight- en the line here, to cut down a grade there, to get rid of this or that grade crossing, to find the be: il and to improve the brid The engineer under whose supervision the were made fit for the fastest long distance pa: vice in America is and his vigilance is um Mr. Katte is a firm a a ties for railroads upon the ground of ulti- mate economy, in spite of the greater first wood. He holds that a line of pon metal ties would be much and at the same timne more elastic, and that incidentally the introduc- n of the metal would thus help in th making of speed. Metal ties are largely d abroad und there isno doubt of their introduction he Mr. Katte’ ring the tracks for the pre | bs and invoived the intricate and rving, most intimate knowledge of a thousand things that would not readily occur to the mind or the lay reader as essential. One innovation that has b found to be of great value is the building of railroad | ridges with solid floors upon which gravel on 3 ballast is laid before the and rails are put down, ¢€ as h roadway. he driving locomotive “pound” tre- mendot upon th s, but well-laid ‘gives sufficle while remain- # strong, to tly reduce the tructive effect of this pounding. When jaid on sleepers, a in turn ly on the be the ballast ing solid a A highly imports ature of th over which exce heavy train rs to run is the vai rails of 8) and 100 | pounds to the 3 now generally eom- } Id Go-pound or quite heavy distributed by son of Rreatest the Ameri the English, nearer m, higher in pro- por 5 with much le bu it is of compar advantage girder form of rail is that it distrib- “3 the weight from a wheel over several es at once instead of allowing it to grind | n upon the tle directly beneath, an r, prevents the rail from bending under the weight, as most of the old form did, making the train constantly travel up | hill, It has been shown by repeated ex- periments that 60-pound rails of the girder type are as efficient and will wear as long as 80-pound rails of the old type. Cost of a First-Class Railroad. “I should say,” said Mr. Katte, “that a single-track road could be lald down over | whole up to 100 tons. | drivers | has b | the full parison between American and British en- gines as to tractive power, the .lifference all being in favor of the engines on this side. This is due to the greater weight borne by the drivers of American en;ines the greater steam-making power in ilers. ‘o matter how bi: the drivers may be,” sald Mr. Buchanan, “if the weight of the machine is not sufficient to hold it down to the track 9nd the boiler cannot furnish m enough to make the wheels go round s ugh, speed cannot be made. Our in building engines, therefore, is fier that will furnish plenty of 1, in order to do that, we are con- ning to increase the heating We alsé aim to secure high 1 re, and that makes it necessary to build the hollers of the very fest material and to put them togethersin the best possible marner.”* In the fast engines on the service between New York and Buffalo the heating surface i square feet. This is not the grates being less than t in size, but is furnished i top and sides of the fire box and flues, of which there are more in the new engines than in the oli ‘There is less difference in size hetween mes than is generally viers twenty-four inches long and nine- teen inches In diameter. Ten years ago the standard of cylinder diameter was but two inches less. The diameter of the drivers of the big engines now in use is 7 feet inches, and each of the four drivers carries ten tons of weight, or 80,000 pounds in all. The total weignt of the engine is 120,000 | pounds, or sixty tons, exclusive of the ten- der, which wi ighs forty tons. bringing the The weight upon the of the old engines was about twenty-six tons, or rather less than seven tons for each driver. Other Speed Problems. Many other and intricate problems had to be overcome before the speed of the pres- ent could be made. Lubrication was one of the and it was believed for a long time that it would be Impossible to keep boxes from getiing hot if run at fifty and sixty mile rates under heavy engines. But there has been no serious trouble from this fter trials of many complicated , the simple soft metal bearing was adopted, and is now in use. But the bear- ings used are very large, thus presenting ‘h wearing surface. Great pains a taken to procure the right kind of oil, and the bearings are most carefully and’ con- stantly Icoked after. So thoroughly has the lubrication pi m been solved that only boxes were reported, during a under 14,000 trains. The suc- bearing in bicy e ts with roller bearings und locomotives, but the present indications are that such bearings will not be adopted, sinc t has been found that while it re- ‘t a train on roller is less pow than on ry ones, ther bear’ The problem of efficient brakes w: also an exceedingly important one when high speeds came to be considered, but it also solved, and so has the problem of building c: strong enough to stand the strain of quick stops. lirection was stri. ‘trated ne artford some years ago, when an sr suffered an accident at he must bring his y, suddenly applied The stop was ed suce! east so far as ning gf was concerned, but the was serious upon the car bodies. did not stop with the wheels. The loosened them from the trucks and id off, causing a gen the meantime the electri ing ready to do some fast promise: neral practice. Th train to man ect They strain thi an hour without dif- understood that r of the arts of that must , Will be t of careful t the Baldy m locomotive works, recently reorgani: in harmon: with the Westinghouse electrical interes! Whether the use of ty on long f: runs will be found as practicable and e nomical as on short slow ones cannot be known till these experiments are com- pleted, but there Is little doubt that before next ar has passed the present fastest time of the English roads will be bested in Americ: perhaps by sted perhaps by the electric current, and very: likely by both. The English locomotive, of which a pic- ture is given, is one in regular service in the Caledonian railway. It has but one pair of drivers, and they are eight feet in diameter. This is understood to be one of the engines that made the recent remark- able speed between London and Aberdeen. DEXTER MARSHALL, (Copyright, 1895, by Irving Bacheller.) CHAPTER [. The telegraph messenger looked again at the address on the envelope in his hand, and then scanned the house before which he was starding. It was an old-fashioned building of brick, two stories high, with an attic above, and it stood in an old-fash- joned part of lower New York, not far from the East river. Over the wide arch- way there was a small and weather-worn sign, “Ramapo Steel and Iron Works,” and ever the smaller door alongside was a still smaller sign, “Whittier, Wheatcroft & Co.” When the messenger boy had made out the name he opened this smaller door and entered the long, narrow store. Its sides and walls were covered with bins and racks containing sample steel rails and iron beams ard coils of wire of various sizes. Down at the end of the store were desks, where several clerks and bookkeepers were at werk. ‘As the messenger drew near a red-headed office boy blocked the passage, saying, somewhat aggressively, “Well?” “Got a telegram for Whittier, Wheatcroft & Co.,” the messenger explained, pugna- ciously, thrusting himself forward. “In there!” the office boy returned, jerk- ing his thumb over his shoulder toward the extreme end of the building, an extension, roofed with glass and separated by a glass sereen from the space where the clerks were at work. The messenger pushed open the glazed door of this private office, a bell jingled over his head, and the three occupants of the room looked up. “Whittier, Wheatcroft & Co.?” said the messenger, interrogatively, holding out the vellow envelope. Yes.” responded Mr. Whittier, a tall, handsome old gentleman, taking the tele- gram. “You sign, Paul.” The youngest of the three, looking like his father, took the messenger’s book and glancing at an old-fashioned clock which stood in the corner, he wrote the name of the firm and the hour of delivery. He was watching the messenger go out when his attention was suddenly called to subjects of more importance by a sharp exclamation from his fath “Well, well, ell,” said the elder Whit- tier, with his eyes fixed on the telegram he had just read. “This is very strange—very strange, indeed!” “What's strange?” asked the third occu- pant of the office, Mr. Wheateroft, a short, stout, irascible-looking man, with a shock of grizzling hair. For all answer Mr. Whittier handed to | Mr. Wheatcroft the thin slip of paper. | No sooner had the junior partner read | the #aper than he seemed angrier than ever. “Strange?” he cried. “I should think it Was strange! Confoundedly strange—and deuced unpleasant, too. “May I see what it is that’s so very strange?” asked Paul, picking up the dis- patch. Mf course, you can see it,” growled Mr. Wheatereft, “and let us see what you can make of it. ‘The young man read the message aloud: “Deal off. Can get quarter cent better terms. Carkendale."" i Then he read it again to himself. At iast he sai confess I don’t see anything so yery mysterious in that. We've lost a con- tract, I suppose—but that must have hap- pered lots of times before, hasn’t it?” | “It's happened twice before this fall,” | | | } | not | the combfation. I told him we had per- returned Mr. Wheatcroft, flercely, “after our bid had been practically accepted, and just before the signing of the final con- tract!” “Let’ me explain, Wheateroft,” inter- | rupted the’ € Whittier, gently. “You | must not expect my son to understand | the ins and outs of this business as we s he has been in the office only understand, exp him to growled Wheateroft t understand it myse! | Cl at door, Paul,” \ tier. don’t want any | know what we are tali | the f. you will case. Paul, that they Mr. Wh a_ third bidder: just soni i a fraction of a cent and stv thought we for cut under us by the job. got e were going to get the bnilding of the Barataria | ntral's bridge over the Little Mackin- | tosh rive el Company that got the contract. | there was the order for the fifty and miles of wire for the Transcon- | tinental telegraph—we made an_extraor- | dinarily low estimate on that. We want- | nd we threw off not only eur profit, but even allowances fer office expenses—and yet, five minutes before the last bid had to be in, the Tuxedo Company put in an offer only a hundred and twenty- The Telegraph Messenger Looked Again at the Address. five dollars less than ours. Now comes the ram today. The Methuselah Life In- nce Company is going to put up a vig building; we were asked to estimate cl framework, We wanted that work—times are hard and there is little , as you know, and we must get work if we can. We meant to have this contract if we conld. We offered to do it at wk s really actual cost of manu- without profit, first of all, and any charge at all for’ office for on capital, for de- of plant. The v! lent of the one v is to all te, is Mr. Carkendale. He told me yesterday that our bid was very kw, and that we were certain to get the contract. And now he sends me_ this,” and Mr, Whittier picked up the telegram ain. Do you mean to say that you think Tuxedo people have somehow been > acquainted with our bids?” asked oung man. hat I'm thinking -no’ was harp answer. “I can’t think For two months we haven't ssful in getting a single one of the big contracts. We've had our share of the little things, of course, but they don’t amount to much. The big things that we really wanted have slipped through our fingers. We've lost them by the skin of our teeth every time. That isn’t acci- dent, is it? Of course not! Then there's cnly one explanation—there’s a leak in this office somewhere.” “You don’t suspect any of the clerks, do you, Mr, Wheatcroft?” asked the elder Whittier, sadly. “I don’t suspect anybody in particular,” returned the junior partner, brushing his hair up the wrong way. “And I suspect everybody ‘in general. I haven’t an idea who it is, Sut°ft’s somebody!” = “Who makes up the bids on these im- pertant contracts?” asked Paul. “Wheatcroft and I,” answered his father. “The specifications are forwarded to the works, and the engineers make their esti- mates of the actual cost of labor and ma- terial. These estimates are sent to us here, and we add whatever we think best for in- terest and for expenses, and for wear and tear for profit. “Who writes the letters making the offer—the one with the actual figures, I mean?” the son asked. “I do,” the elder Whittier explained. “I have always done it.” “You don’t dictate them to a typewriter?” Paul pursued. “Certainly not," the father responded. write them with my own hand—and what's more, I take the press copy my- self, and there is a special letter book for such things. This letter book is kept al- ways in the safe in this office—in fact, I can say that this particular letter book never leaves my hands except to go into that safe. And, as you know, nobody has access to that safe except Wheatcroft and me.” “And the major,” “corrected the junior partnel “No,” Mr. Whittier explained, “Van Zandt has no need to go there now.” “But he used to,” Mr. Wheatcroft per- sisted. “He did once,” the senior partner re- turred, “* but when we bought those new safes outside there in the main office there was no longer any need for the chief book~ keeper to go to this smaller safe; and so, é “Mike, whé shuts up night?” last month—it was while you were away, Wheatcrogt—Van Zandt came in here one afternoon .and said that as he never had cece: nm te go to this safe, he would rather ave the responsibility of knowing th ico at fect contidenca in him— “T should think so!’ broke in the ex- plosive Wheateroft. “The major has been with us thirty years now. I'd suspect myself of petty larceny as soon as him, “As I said,” continued the elder Whit- tier, “I told him that we trusted him per- fectly, of cougse. But he urged me, and to please him I changed the combination of th safe that afternoon. You will re- member, Wneatcroft, that I gave you the new word the day you came ba ON I remembe: said Mr. Wheat- I don’t see why major don want 'o know that te. Perhaps he is he ars nuw. He mt be I've been thinking for some time he looked worn.’ utes later Whittier, Mr. med priva ely through n Zandt, whose high d that he could ove: e, had been watching r ce the messenger had deliv- dispatch. plac te of ered th CHAPTER IL. After luncheon, as it happened, both the senior and the junfor partner of Whit- tier, Wheatcroft & Co. had to attend meetings, and they went their several . leaving Paul to return to the office When he came opposite to the which bore the weather-beaten isn of the firm he stood still for a mo- t and looked across with mingled pride and affection. The building was old fashioned, so old fashiored, indeed, that only a long-established firm could afford to occupy it. It was Paul Whit- tler's great grandfather who had founded the Ramapo works; there had been cast the cannon for many of the ships of the little American ray that gave such a Good account of itself in the war of 1812. Agair, in 1848, had the house of Whit- tier, Wheateroft & Co.—the present Mr. Wheatcroft's father having been into partnership by Paul's grandfather— been able to be of service to the govern- ment of the United States. All through the four years that followed the firing on the flag in 1S6L the Ramapo works had been run day and night. When peace came at last and the people had again jeisure to expand a large share of ihe rails needed by the rew overland roa which were to bind the t and the West together in iron bands, had been rolled by Whittier, Wheateroft & Co. Of late years, as Paul knew, the old firm seemed to have lost some of its early en- ergy, and, having young and vigorous competitors, it had barely held tts own. That the Ramapo works should once more take the lead was Paul Whittier’s solemn purpose; and to this end he had been carefully ned. He was now a young man of nearly twenty-five—a tall, handsome fellow, with a full mustache over his firm mouth, and with quick e: below his curly hair. He had spent four years in college, carrying off honors in mathematics; he was popular with his classmates, Who made him class poet; and in nis senior year he was elected president of the college photographic society. He had gone to a technological institute, where he had made himself master of the’ theory and practice of metallurgy. After a year of travel in Europe, where he had investi- gated every important steel and iron works he could get into, he had come home to take a desk in the office. It was only for a moment that he stood on the sidewalk opposite, looking at the old building. Then he threw away His cigarette and went over. Instead of entery re, he walked down the pen for the hea When he came opposite the private of in the rear of store he examined the @oors and the windows carefully to see it he could detect any means of ingress other than those cpen to everyboc : As Paul entered the private office he found the porter there putting coal on the fire. Stenpipg back to close the glass door behind him, that they might be alone, he sad Mike, who shuts up the office at night?” Sure I do, Mister Paul," was the prompt answer. “And do you open it in the morning?” the young man asked. “I do that,” Mike responded. Do you see that these windows are al- fastened on the inside?” was the next way query. Yes, Mister Paul,” the porter replied. “Well,” and the inquirer hesitated brief- ly before putting this question, “have you found any one of these windows unfasien- ed any morning lately when you came here?” “And how did you know that?” Mike re- turned in surprise. “What morning was it?” asked Paul, pushing his advantage. “It was last Monday mornin’, Mister Paul,” the porter explained, “an” how it was I dunno, for I had every wan o’ the windows tight Saturday night—an’ Mon- ; wagons day mornin’ wan o’ them was unfastened whin I wint to open it to let a bit o’ air into the office here.” “ “You sleep here always, don’t you?” Paul proceeded. “I've slep’ here iviry night for three year now come Thanksgivin’,” Mike replied. “I've the whole top o’ the house to myself. It’s an iligant apartment I have there, Mister Paul.” When Mike had left the office, Paul took a chair before th@/fire and lighted a cigar. For half an hour he sat silently thinking. He came to the conclusion that Mr. Wheatcroft was right in his suspicion. Whittier, Wheatcroft & Co. had lost im- porent contracts because of underbidding jue to knowledge surreptitiously obtained. He believed that some one had got into the store on Sunday while Mike was taking a walk, and that this somebody had some- how opened the safe. There was never any money in that private safe; it was intended to contain only important papers. It did contain the letter book of the firm’s bids, and this is what was wanted by the man who had got into the office and who had let himself out by the window, leaving it_unfastened behind him. What grieved him when he had come to this conclusion was that the thief—for such the housebreaker was in reality— was probably one of the men in the em- pioy of the firm, It seemed to him almost certain that the man who had broken in knew all the ins and outs of the office. And how could this knowledge have been ob- tained except by an employe? Paul was well acquainted with the clerks in the cuter office. Ther+ were five of them, in- cluding the old bookkeeper; and although pone of them had been with the iirm as long as the major, no one of them had Leen there less than ten years. While Paul was sitting quietly in the private office, smoking a cigar, with all his mental faculties at their highest tension, the clock in the corner suddenly struck three. Paul swiftly swung around in his chair and looked at it. An old eight-day clock it was, which not only told the time of day, but pretended also to supply_miscel- Janeous astronomical information. It stood by itself in the corner. For a moment after it struck Paul stared at it with a fixed gaze, as though he did not see what he was looking at. Then a light came into his eyes and a smile flitted across his lps, He turned around in his chair slowly and measured with his eye the proportions of the room, the distance between the desks and the safe and the clock. He glanced up at the sloping glass roof above him. Then he smiled agiin, and again sat silent for a minute. He rose to his feet and stood with his back to the fire. Almost in front of him was the clock in the corner. He took out his watch and compared its time with that of the clock. Apparently he found that the clock was too fast, for he walked over to it and turned the min- ute hand back. It seemed as though this was a more difficult feat than he supposed or that he went about it carelessly, for the minute hand broke off short in his fingers. A spasmodic movement of his as the thin metal snapped pulled the chain eff its cylinder, and the weight fell with @ clash. All the clerks looked up; and the red- headed office boy was prompt in answer to the bell Paul rang a moment after. “Bobby,” ssid the young man to the boy as he took hat and overcoat, “I've just broken the clock. I know a shop where they make a specialty of repairing time- pieces like that. I'm going to tell them to send for it at once. ve it to the maz who will come this afternoon with my card, Do you understand?” “Cert.," the boy answered. “If he ain't got your card, he don’t get the clock. “That's what I mean,” Paul responded, as he left the office. Before he reached the street door he met Mr. Wheatcroft. Paul,” cried the junior partner explosive- ly, “I've been thinking about that—about that—you know what I n:ean! And I've de- cided that we had better put a detective on this thing at once “Yes,” said Paul, “that’s a good {dea. In fact, I had just come to the same con- clusion. I—~” ‘Then he checked himself. He had turned slightly to speak to Mr. Wheatcroft, and row he saw that Maj. Van Zandt was Standing within ten feet of them, and he noticed that the old bookkeeper’s face was strangely pale, (Continued in Monday’s Star.) «—— DR. PARKHURST’S EARLY TRAINING. The Home He Was Born, Loved and Chastixed In. If I speak confidently and feelingly upon this point it is because I know how much I owe personally to the fact of being brought up in a home where I was taught to appre- ciate the greatness of righteous ii the vastness of its meaning, the advantaze of ubmitting to it, and the serious risk of ng it, writes the F Chari in the Ladies’ Hone Jour nal. No anarchist could ever have grad- uated from the home I was born, ioved and in. Such ehildren who know but that of caresses and sweetmeats, and mekes me more than pity the parents who have neither the discernment in their men- al constitution nor the iron in their mo} ttution to perceive that mpthing whi a child can know or can win can begin to take the place of sense of superior authori- ty, and of the holy right of that authority to be respected, revered and obeyed. The moral strength of a man is measured pretty accurately by thg cordial reverence with which he regards whatsoever has the right to call itself his master. Estimated by this criterion, the average American boy is a discouraging type of humanity, and is a severe reflection upon the crude attempts at manhood manufactured by the typical American home. If our homes cannot turn out children that will respect authority, there will be no authority in a great while either at home, in the state, or anywhere e.se, that will be worth their respecting. A Story With a Moral, From Life. AT BEINN BHREAGH The Summer Home of Alexander Graham Bell. A LOVELY NOOK IN NOVA SC How Mrs. Bell Has Established a Native Industry. LACE-MAKING AND SCHOOLS (Copyright, 1895, by Johnson, Bacheller & Johnson.) NE OF THE MOST interesting and least known of American summer colonies is Baddeck, on the Is- jand of Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. Bad- deck does not figure in the watering place correspondence of the Sunday newspapers. It is not noted for its casino, or its golf links, or its hops. Neither is it a yacht- ing rendezvous. Yet the number of its cot~ tagers is increasing steadily, and the ef- forts put forth by one group of its warm weather colonists, in behalf of the all-the- year-round populations, are making it the seat of an important industrial experi- ment. Some five or six years ago Mr. and Mrs, Of those in his employ many were the original owners of the soil become “land poor” and forced to part with their patri- mony through dire necessity. Large sums of money are spent by Mr. Bell in the im- provement of the country round about Beinn Bhreagh, connected with Baddeck by the little ferry boat that plies back and forth with the mails twice a day, until the once impassable forests that cover the hills for miles inland are today pierced in every direction with smooth roads, over- hung by the grand old pines and hemlocks. *Some idea of the condition of the country five years ago may be obtained from the . experience of a house party who set out by boat from Baddeck and landed at Beinn Bhreagh with the intention of making their way across the point to the shores of the Braddore lakes. When the party left the landing they were forced to hew their way through the tangled under- growth in many places, using hatchets with which each guest was provided to cut a foothold in the rocky soil. In the rapid march of improvement a driveway stretches across the peninsula and ramifies- inland for many miles toward the sheep farms beyond. Some twenty-five miles from Baddeck, in the heart of the country, there is a beau- tiful little hunting lodge, occupied by Mr. Bell and Mr. George Kennan during a portion of each season for the cariboo hunt. An extensive laboratory adjoins Mr. Bell's house at Baddeck, in which most of his scientific experiments are conducted. In this laboratory the professor spends a large part of his time, and here are per- fected many of the inventions that have made his fame world wide. To increase yet further the attractions of his chosen retreat, Mr. Bell has built a house boat, which is kept anchored in the little harbor at the foot of his grounds. “Mabel Beinn Bhreagh” is the name of this dainty craft, given in honor of his wife and his pet hobby. The boat is pat- terned upon the plan of a catamaran and propelled by a small tug engaged by Mr. Bell for the transportation of the mails between Baddeck and Beinn Bhreagh. The river Denny, one of the most beauti- ful of the little streams which indent the coast, is a favorite tract for these ex~ cursions, :tudded, as it is, with countless tiny islands. When the passage becomes too narrow for the tug the house boat ig BADDECK BAY. Alexander Graham Bell cf Washington, D. C., were making a pleasure tour aleng the coast, in company with Mrs. Bell's parents, Mr. and Mrs. Gardiner Hubbard, when the rugged cliffs, the bright skies and the great pine-clad forests of Bad- g@eck bay caught their attention. Upon a towering crag overlooking the water, which here has the thunderous rise and fall of the Bay of Fundy, they built a cottage. Every summer since has found them in residence, and for a few years past Mr. and Mrs. George Kennan have been of their neighbors, and have joined them in the work they found to their hand. It was carpets that first interested Mrs, Bell. When she came to know the women about her, she found maay of them the from the uncertain sea. be of use, she praised their bright-hued carpets, hand-woven, from gay wools, and bought so many of them that she and her friends and her friends’ friends had’ more than they could walk on in two or three life-times, To develop this carpetanaking industry, to find a marxet for the preducts and thus to supply an occupation that should keep the older girls at home, In- stead of secing them driven to the New England towns for a living, became with her an absorbing consideration. One of Mrs. Bell's first practical steps was to start a school for the little ores too oung for tleld tasks. With the help of eorge Kennan, classes were formed, fter the kindergarten model, e tots and their bigger sisters, § running as high as sixteen, w trudging ten mil barefoot over the cliff: in order to attend. As the school grew favor the mothers of the chil also, whenever their brief leisure would allow. Knitting was a favorite occupation, and, remembering the great revival of the lace industry among the Irish peasantry, Mrs, Bell Getermined to introduce the same thing into her little colony, With this plan in vicw, she tried to get Irish teachers, offering salaries from her own purse, well as the expenses of the voyage. Bs nobody could be found to settle among the ‘olk of Cape Breton. Still, undaunted, Mrs. Bell got patterns and teachers from Boston and before long the class in lace-making was in full swing. Sy rapid was the progress of the Cape ston girls that before long the fineness and beauty of the designs more than equaled the original samples. Mrs. Bell's efforts throughout were ably seconded hy Mrs.Kennan and the sale of Cape Bretoy lace was pushed until today the supply more than meets the demand. This was a not altogether unexpected check, but not the less discouraging. So long as the duty remains as at present, there is small pros- pect of lace-making proving profitable as a means of livelihood. ‘There is another difficulty to be met also. During the winter months the education of the children was at first continued by the elder scholars, but owing to the impossibil- ity of obtaining employment at home, these one by one have gone to lock for places In the large cities of the east, and paid teach- ers have been engaged from Boston. The seeming impossibility of making a living at home has been Mrs. Bell's greatest dis- couragement, as no sconer gre the children trained in lace-making and various kinds of needlework, with the view of educating | the younger ones in their turn, and by de- | ating a permanent industry, than ssity compels their departure. In this way each year the number of workers de- creases. Boston is the usual objective point of those who leave home to make their fortunes, but at least two-thirds of the wanderers return after a year or so, broken in health, many to die of consump- tion. Accustamed to the free open air of the mountain region the Cape Breton folk are unable to endure a sedent: life in a climate less suited to their constitutions. he average attendance at the school is from fifty to seventy-five. There are at present five resident teachers, three of whom are from a distance on a regular salary. Owing to the rigors of the climate these are unable to remain during the win- ter months, when the classes are left to the care of but two native born. | The classes have long overtiowed Mrs. Bell's cottage, and a special building, better suit- ed to the Increased numbers, has been s: cured. Originally used as a mission church, jong since dismantled, this structure has been repaired and fitted up as a school house with club rooms and library. Here during the sump qnonths the classes hear lectures from well-known men, who vist the spot from Boston, Washington an other cities, either as guests of Mr. and Hl, or tourists attracted to the spot th. Today the community iterature and a of sts sey’ asses in lit Current Events Club, mz daughters of resi deck. In full sympathy with his wife Mr. Bell has instituted the Worki Club, among the men in his e1 z *p herders on hi 1 Beinn Bhreagh. Gradually it | sope until at present its mem- | up is over a hundred. Mr. Rell 5 up the t its weekly meetings. Through M: "s interest a free library has beer established, and during the bitter cold and fogs that infes certain se, sons, opportunities are afforded for study and entertainment, otherwise unattainable. Just across from Baddeck, at “E Bhreagh,” Mr. Beil has purchased an fr mense tract of pine clad forests jutt out, peninsular like, into the Bras d'Or lakes on the north and the Bay of Fundy on the south. Here he has opened up stock farms in the higher regions, upon which he has already lavished a fortune in | improvements. His sheep ranches are Mr. | Bell's hobby. Hundreds of fine bred sheep roam over the stubble fields and brows upon the herbage of the rocky summits, undisturbed by fear of slaughter. Every year Mr. Bell adds to his herds, just as a biblomaniac collects rare and treasured volumes. It goes without saying, that these ranches are run at a very consider- able annual expense. | propelled by two canoes in the hands of sturdy paddlers. When their destination is reached the boat is secured in its place by means of ropes stretched from island to island. Then begirs the poetry of exist- ence. Among the towering pines and hem- locks, what more perfect dream life coulds be desired? At night hundreds of lanterns, Uke fireflies, dot the surface of the water, gliding hither and thither, strung from the bows of tiny row boats or birch canoes. Among the most enjoyable features of this floating existence are the charmingly in- formal entertainments given by Mr. and Mrs. Bell, who know how to enjoy as weil as to work, and to give as weil as to ree ceive. ANNA P. THOMAS. — WORKBASKET TRIFLES. Three Visitors From the Country Are Shocked, ‘From the New York Tritume. The workbasket of the up-to-date woman of leisure is provided with many costly trifies, the use of which is not directly ob- vious to the uninitiated. This fact was re- cently impressed upon the writer at the counter of a jewelry establishment. A group of women, whose manner and ap- pointments indicated that they were stran- gers in the city, were looking at gold thim- bles, and, incidentally, at various other ar- ticles displayed by the clerk. “Look here, Mary Ellen,” said the oldest of the three, holding up to view a flat little square of gold with ric! chased edg “What do you reckon this is?” “It don’t look like anything in particular to me,” answered Mary Elien after close It's a thread-winder, and it's worth $). “Nine dollars for a thread-winder!” ¢ claimed Mary Ellen, aghast at the idea “Well! I never! I always wrap my ol scraps of thread or silk round an empty Spool or a piece of cardboard, like the scooped-out piece of wood the boys at home wind their fishing lines on. That's right convenient, though,” she added, examining the pretty baubie interestedly. “Here's something else,” said the third woman, balancing between her fimgers a pencil-like arrangement exquisitely chased and having a smooth oval bulb at either end. “I wonder what this is for?” and she glanced appealingly at the clerk. “That's a glove darner,” he explained, much amused at her perplexit “And how much does it cost leven dollars. The trio exclaimed in horror at this reve- lation of extravagance, and Mrs. Mary El- len remarked sternly that $11 would supply her with gloves for two years, All three examined the glove darner crit- {eally, and then, pursuing their investiga- tion, speculated in turn as to the merits of the solid gold thimble holders, emery hold- ers, needle cases and other articles that seemed curious to them, Finally, when a finger protector was shown, Mrs. Mary El- *s patience became exhausted. ‘hese idle women ought to be proud to show a few needle pricks on their forefin- eer,” she exclaimed. “I'd like to know how @ little needle prick can hurt!” She did not conceal her amazement that so insignificant, every-day an affair as a little round tape measure could be contriy- ed to cost ${; and a small ivory case, equip- ped with tiny gold-handled scissors, needle — case, thimble and bodkin, the value of which was $100, nearly took away her breath. “It seems outrageous to squander so many doilars on nonsense,” she declared energetically as the party left the shop. ———._ -+e+-__ She Did Not Parchase. From the New York Weekly. Woman—“Have you any stove lifters?” Hardware Clerk (from Boston)—“We have stove lid lifters, madame. I presume that is what you mean.” Woman (defiantly)—“I mean stove lift- ers?’ Clerk (patronizingly)—“A stove lifter Would be something to lift up a stove. A jJackscrew, for instance.” Wom: “Have you any jack- Cler lieve so, Wot (surprised)—“Y-e-s, madame, I be- in the basement in (meditatively)— ‘Are they silver- Clerk (dumfounded! Woman (triumphantly want 2 stove with a jac asn’t plated. I'll go deal at some store where they have a better class of custom, keep aristocratic goods. Good morni No, madam ‘Then I don't Losing ground.—Life,