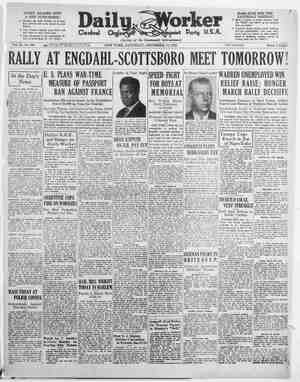

The Daily Worker Newspaper, December 17, 1932, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Pichia 4 a i | ‘ & » tO resist disease, the enemy from DAILY WORKER, NEW YORK, SATURDAY, DECEMBER 17, 1932 sath niacin Dail Central orker’ Perty USA | Published by the Comprodaily Publishing Co., Inc., daily exeept Sunday, at M0. St., New York City, N.¥. Telephone ALgonquin 4-7956. Cable “DAIWORK.” and mail checks to the Daily Worker, 56 E. 13th St., New Yerk, 6. ¥. SUBSCRIPTION SATSBI By mail 3 months, $2; 1 month, We w York City. Foreign ond 33, verywhere: One year, $6; six months, $ excepting Borongh of Manhattan and Bronx, Canada: One year, $9; 6 months, $5;_3_months, An End to All Evictions working class, employed and unemployed, there is no immediate need than organized mass struggle for drastic ainst evictions y courts from January to October ,inclusive, this third there were 259,602 eviction processes according to the of- mary figure of five per family in estimating ap- of heads of families and thzir dependents af- of landlords, real estate sharks, police and i part time workers, would approach “rotten with its ever increasing mass unemploy- undreds of thousands of families have ves, to make one apartment, tenement Consequently, instead of 1,300,000 ntices, on the basis of five per family, the neighborhood—probably in excess of Translated into verms of poverty, hunger and other forms of human y, these figures stagger the imag‘nation. against evictions in New York City. There t evictions in other cities, notably in Chicago. for reductions in rent. The Communist Party ls have taken a leading part in these battles. k certainly typifies the general situation S. Viewed from this angle it is clear ed some of the more flagrant in- capitalist offensive. t not o is the widest and most militant organ- needed but that it is entirely possible to bring ainst the eviction atrocities on a wholesale scale ions of the working class, poverty-stricken pro- ed idie class forces. organizations and the Communist to the tremendous scope of the vital necessity for extending the mass struggle on th the fight for immediate cash winter relief ance. of unemployed and part time Committee of the Communist Party of the U. S. A. greets Revolutionary paper—L’Unita’ Operaia. This paper led to win the large masses of Italian workers in ‘this lutionary way out of the present crisis of capitalism. ye million Italian workers in the United States. e in basic industries such as coal mining, steel, Their standard of living has been cut to the and the capitalist offensive. The Italian work- hardest hit by mass uncmployment, wage cuts and deportation of foreign-born workers. To this persecu- the Italian workers are answering with willingness to Hundreds of them are entering the ranks of oil fluence of fasctsm spread among them by the is press, and from the illusions spread among press which paves the way for fas- well as the Italian fascist embassy in Wash- as the role these workers will play in s of the proletariat in Italy. Proof of this was deprived of second class mailing priv- as visited upon the “Ordine Nuovo” which ‘L’'Unita,’” a revolutionary magazine, was it office authorities. that behind this persecution in the Italian embassy. pon the It: bs 's to support “L’Unita’ Operaia” by y sénding financial contributions to it, and above ze the paper among the broad masses of Italian workers ow more powerful and become a daily paper. ll our Party workers to see every Italian Party mem- ber becomes a subscriber, a supporter and also a correspondent for L’Unita’ Operaia. The lterature agents of our sections and units throughout the country must at once call the office of the paper: 813 Broadway, New York City, or write to P. O. Box 189, Station “D,” New York City, and make arrangements for a bundle order of the paper to be sold in the Italian neighborhoods and factories where Italian workers are employed. succ2ed declared “ Our Di: t and Section Organizers must see to it that some of our best Italian co assigned to build organizations among Italian Workers to str mass base of support and circulation of the MAKE L'UNITA’ OPERAIA A POWERFUL WORKING CLASS N THE MAJORITY OF THE ITALIAN WORKERS FOR THE REVOLUTION! LONG LIVE L’UNITA’ OPERAIA! Central Committee of the Communist Party of U.S.A. ! e he working class cannot be neglected by us, it | portance of the Italian workers in the class | J. cas Engdahl’s Role in Fight for Scottsboro Boys By WILLIAM L. PATTERSON. {General Sec’y Int'l Labor Defense) MEMORIAL tribute to J Engdahl, N: , of the In gles of the working class. could not have been accomplished if there had not been some under- nding that Scottsboro was an national oppression. and re—that a blow in defense of ‘o liberation was at once an Me om 28 glee act of defense of the struggles of workers the whole working class. Ameri- be there. Tt imperialism helped momen- Sanh who > y to strengthen German im- Meade: iingdahl died inthe sep, | 2 of England. Imperialism Aye feces oh ‘r- shows its international relation- ete dia ship when the struggles of the He died in front ranks of the struggle. J. Louis Engdah] was a martyr of the class struggle. He was né less a victim of the bloody terror of the ruling class than if he had working class threatens any seem- ingly separate part. A blow at American imperialism weakens Eu- ropean imperialism. Scottsboro is an integral part of the struggles of the toiling and exploited masses of jaid down his life in the fiercer i lash of armed forces. Harassed | ‘RE WONG. ts 6 eenational by secret service men of America : ‘ eid end foreign countries, persecuted izer of Scotisboro, is gone, but the victory of Scottsboro is not yet | | | by the 1 f 16 E a] ~ y the police of 16 European coun: | complete. A crowning monument | tries, Engdahl was so weakened from the struggle with the class enzmy without, he had no power to him would be a complete vic- tory. Victory in the Scottsboro case personified by nine innocent Neher | tea bid means their uncondi- oa e n tional freedom; Scottsboro is the gene could have been no more | srmboi of an oppresied nation, ite aed climax to his life than that victory marks the end of its ‘op: Pe should have died in Moscow, | 7c " Rita of the workuty oseoW, | pression nationally; victory in was while J. Louis Engdah! was its general secretary that the In- ternational Labor Defense and its Supporters leid the basis for com- plate victory in the Scottsboro case Only a partial victory was achieved in his lifetime. That partial vic- ‘tory was realized because the Scottsboro case was international- tzed—because the current of Negro liberation was merged with strug- Father- | s m | Scottsboro, the symbol of world op- Mes tat_saved ‘Tom Money's | PTessio%, theans a world lberated, fooney rs i ; rnc presser BY defending the Scottsboro boys, & links them together. There is the struggles against mass un- ‘an inseparabl: link between the | ©™Ployment and mass starvation Struggle Engdahl led and the so- | 2% defended. By defending the Cialist construction of the Russian | Scottsboro boys, American im- workers. ‘The one gives added | Perialism is attacked. By attack- strength to the other. ing American imperialism the so- * , . cialist fortress is defended. By de- fending the world of socialism the imperialist world is attacked. J. Louis Engdahl saw this. As an enduring statue to J. Louis Engdahl, Labor Defense into an irresistible weapon of working-class defense. The memorial to J. Louis Engdahl should launch the victorious march toward which he led so decisive a forward step. This | n to support the toppling | build the International | ‘ANOTHER LITTLE X-MAS GIFT FOR YOU, BROTHER!” £< BRO SO OREICIAN —By Burck Frame-Ups of TampaVictims By LUIS ORTIZ ‘Here we have a case, born of the class struggle, in which Amer- ican and Latin American workers who have taken their places in the revolutionary movement of the United States, to which they be- long; who had the courage to raise the banner of the Communist Party of the United States. with its program of national liberation of the oppressed Negro people in the United States, in the Southern State of Florida, with its criminal system of jim-crowism, segrega~ tions, etc., for the Negroes, rotting in jail and the murderous chain- gangs. ‘This fact must serve to bring the Party and the whole revolutionary movement of the United States to frankly look at the true causes which underlie the underestima- tion of this case. ‘HE Tampa case, in which col- onial workers from Cuba, Mex- ico, Uruguay, and other Latin- American countries, are victims of the most vicious frame-up, must be the signal fora general mobil- ization of the revolutionary work- ing class and: toiling masses in the United States, under the leader- ship of our Party and the Inter- national Labor Defense, Forward to the defense of the ‘Tampa prisoners! Long live the unity of the Am- erican and Latin American toilers! (THE END.) The Battle of Wilmington The Courageous Fight of the Militant Hunger Marchers By MOISSAYE J. OLGIN. 'VER since we left New York we knew that trouble was brewing in Wilmington. Wilmington, we were told, would not permit a parade of the Hunger Marchers. Wilmington would not permit us even to leave our trucks. Press, |. pulpit-and city administration had | | | | |} And here, conducted an insidious propaganda against the Hunger March. ‘The Hunger Marchers had to pre- pare. We had to reckon with the possibility of an attack. We dis- cussed the question in our trucks. We made a unanimous decision. And there could be only one de- cision: We demonstrate on the streets of Wilmington! WE SHOW OUR STRENGTH! When we arrived in Chester, Pennsylvania, twelve miles distance from Wilmington, we were perfect- ly aware of the fact that the stronger our stand in this last stop before the state of Delaware, the more. the Delaware authorities would appreciate our power. It is necessary to understand the psychology of the rulers and their armed servants in relation to the March. They know that there are in the world men of power and | beggars. The men of power de- | serve respect; the beggars deserve | contempt. A man like DuPont is | @ power; he owns Wilmington; he owns its plants and its ammuni- tion factories on the other side of the Delaware, in New Jersey; Governor Buck of Delaware is proud to have married into the house of the Du Ponts. A Du Pont certain- ly deserves respect. The Hunger Marchers, on the other hand, are beggars; they wear poor clothes; they are unshaven, underfed; they hhave'no food stores and must rely on outside aid; we had no place to sleep in and lay down wherever we found a spot. According to all rules and regulations of capitalist society, people like the Marchers were to be meek, submissive, docile, thankful for not being locked up. the unexpected thing happened; these beggers came with a pride and a dignity, these tatter- ed individuals did not beg, but de- manded, like one who has power. They did have power. What could the authorities do with this kind of a crowd? a Sig ‘HEY were in a quandry and we knew it. We also knew that everything depended upon our stand. If we are better organized, more determined, if the rank and file understands better the whole plan of action, it will be easier for us to confuse the rulers. We marched into Chester like a well-organized army. We paraded through the city in excellent order. We arrived at the center of the city, in front of City Hall and we told the workers about ourselves and our aims. We told them we were going to parade through the streets of Wilmington under any circumstances. “We will fight to the last ditch,” said Carl Winter, one of our leaders, and his words were heard not only by the workers of Chester, but also by the police; they were heard by the capitalist reporters who transmitted them to Boyd, the Wilmington chief of police, and Black, the superintend- ent of public safety. who learned that. the Hunger Marchers (Our Column) were an army of 1,200 united, embittered and determined fighters. OUR PROGRAM AND TACTICS Between Chester and Wilmington our trucks tightened their discip- line and. made their last-minute preparations. Hers are the major points of our program and tactics | as worked out on the road and agreed to by every member of every truck: 1. We parade through Wil- mington with banners, placards, music and singing. 2. Individual marchers receive orders from nobody but their commanders. 3. We do not attack the po- lice, but if the police attacks we defend ourselves. 4. We do not break our ranks if individual marchers are arrest- ed. 5. We defend the Negro com~ rades who would possibly be the first to be attacked by the po- lice; we do not allow them to be snatched out of our ranks. 6. The Negro comrades defend themselves also, not waiting for their white comrades. 7. We hold at least two open- air meetings in Wilmington. 8. We stay over night in Wil- mington. When we reached the city limits of Wilmington, we were all taut like a bow string. A delegation had been sent by us to inform the police officials that we were going to parade. The answer was “No, you won't parade.” However, when we all approached, when the comrades left the’ trucks and, obeying commands, formed a Powerful column in as short a time as five minutes, when the chief of police and the superintendent of public safety, standing at the head of a few dozen policemen, realized our power and saw our comrades declaring bluntly, “We are going to parade,” they said, “Go ahead.” I do not think they liked it very much. | WE PARADE We paraded. We marched with unusual agility; we kept our ranks closed; we sang; we exclaimed; we chanted in chorus, and there was a hot flame of enthusiasm surg- ing through the ranks. The population poured into the streets to watch us. Many applaud- ed. The crowds stood in thick tows all along the streets, some- times several hundred in one block. We passed thirty-two blocks. When we saw & Negro crowd we chanted: “Negro and white, Unite and fight.” ‘This never failed to call forth enthusiastic applause from among the Negroes. ‘The Column kept marvelous or- der. The marchers walked like one, rhythmically, crisply, keeping time, heads erect, eyes ablaze. It wasn’t & mob, no indeed. It was not a crowd of beggars either! It was an organization of fighters! ee 18 WORD must be said about the marchers. They were elected haphazardly on bread lines, in pool Tooms, in flop houses, in block com- mittees. Most of them were a raw element, just drawn into the move- ment. Most of them had never participated in a clash with con- stituted authorities. For the first time, they were learning the mean- ing of revolutionary proletarian struggle. They were awakening to a realization of something over- whelming: the power of their clscs. We approached the garage at the corner of Front and Madison Sts., where about 800 of us were to stay over night. Another group of about 200 was sent to the Italian Labor Lyceum. A third was to stay over night in a Polish Club, in the for- mer building of a Catholic Church. ‘There were many women in this latter division. IN THE POLISH CHURCH With shouts and laughter we poured into the Polish church. A large building—one big hall with a platform; a few steps leading down to a kitchen in the basement. The hall was almost empty except for a few dozen chairs. But the entire building was well heated and the floor was clean. We sat down on the chairs and on the floor—some 250 men and women. There was a great deal of shouting, singing, joking. We were all somewhat in- toxicated with our own victory. Supper was served down below. The tables could seat only about 80 and we had toeat in three shifts. But that made no difference, since the meal was gobbled up in a minute or two. Exhilirated after the march, and cheered by the warmth of the rocm, we started dancing. Somebody banged the piano which we dis- covered on the platform. Soon several dozen comrades were whirl- ing around the hall. This did not prevent others from spreading their belongings on the floor and going to sleep. It was 9 o'clock. Soon everybody would settle down for a night's rest. KNOW OF POLICE ACTIVITY We knew that there were police detachments on the corner of Chestnut and Adams. .We knew that a street meeting was to take place not far from the church. We knew, however, that, our speakers were to address the local crowd. For us, the mass of the marchers, the day was over. Still, when we heard that a meeting was in prog- ress right in front of the church, many of us stepped out to listen and to support the speakers. We learned that the police had dis- persed the meeting scheduled to take place at Chestnut and Adams, and that this was our second at- tempt to address the local people. We saw police everywhere. Squads of police. Uniforms all around. Trucks with mounted ma- chine guns. Policemen armed with sawed-off shotguns. They were forming groups and lines in front of the church, trying to separate the mass of Wilmingtonians gath- ered in front of the church. ND this is the scene before the battle started. Police in various corners of the street. Police in front of the church on the oppo- site sidewalk. Police in the mid- dle of the street flanking the crowd. Our speaker, at the head of the stairs leading from the church to the sidewalk. Around our speaker several dozen. hunger marchers, while the majority re- mained inside the building unaware of what was going on outside. The police were obviously in an ugly | temper, but who cared. We had carried out the first part of our program. We were determined to carry out the second part as to an open-air metting. Our activities were to serve for the local work- ers as an example of how organ- ization, and determination could break police bans. The battle started with the po- lice beginning to mount the stairs. Policemen began to push our speakers, Some attempted to make arrests, The march- ers offered _ resistance. Police clubs were raised, but strong hands seized police arms, fists met f.sis, The biuecoats be- came enraged. They didn’t ex- pect that, They began to push us back from the porch into the church, The marchers entered the hall but refused to let the police in. They locked the door and pushed against it in a big compact mass, The police were locked out. In the kitchen below a few dozen women gathered. There is a door leading from the kitchen to the street. The police tried to break that door. But the women built a barricade of tables and chairs. The policemen brought hatchets to break the door. In the meantime the ‘electric light went out in the kitehen. When the bluecoats finally forced their way into the kit- chen, they were met by. chair legs, wielded aptly. A battle en- sued, with the women fighting even botter than the men. “The wom- en fought like tigers,” said the Wil- een Press the following morn- e. . . a main hall was beseiged for awhile with the police unable to get in. Then, tear gas bombs were thrown ‘from outside into th2 hall. Many exploded. Some were snatch- ed by our comrades and thrown back through the window before they exploded. The big hall was filled with gas. The marchers coughed. Their eyes smarted., First they tried to lay down on the floor where the gas was not as heavy. Some comrades broke all the win- dows to let air in. Others were throwing parts of the ‘chairs into the police forc2 outside. Finally a comrade suggested that all leave the hall through a side window opening into the street. The com- rades, about 200, mostly women, soon found themselves in th? street —and here the mass battle only began. PROLETARIAN RESISTANCE The marchers must be given due credit. They showed an example of powerful proletarian resistance. They did not attack but they did not take attacks passively. They did: not provoke, but they did not allow themselves to be provoked. A policeman drew a gun. The mo~ ment was tense. H2 was in a white rage. One of the woinen comrades began to talk to him. / She did not say anything soothing. She just said, “You are a coward. A man with a gun against unarmed people. ‘You better put your gun away and step up; Jet's see how you can in Du Pont’s City fight.” While she was talking she was moving down the stairs, facing the policeman, drawing closer to him. He finally put his gun away. The comrades never yielded ground. They fought for every inch. They returned blow for blow. One policeman tries to arrest a Negro comrade. Several comrades sur- round him, open his arms, free the Negro. Another policeman lifts his club over a comrade’s head—a strong hand seizes the club, turns it the other way and soon there are‘ blue marks on the policeman’s face. A woman comrade is being hammered with a club over her shoulder. It is painful. But, as she tells subsequently, “I caught him by his necktie and began to pull; he knocks with his club while I pull his tie; it hurts me but I know it hurts him too: he is choking.” A heavy Negro woman is being poked in the ribs by a policeman. She told us later sho didn’t want to start a fight. She was just draw- ing away. But then a little white woman comrade, just a slip of a girl, saw a Negro comrade being attacked and rushed to her rescue; she screamed, she scratched, she bit the policeman’s hand. “Well,” says the Negro comrade, “T sees this little kid fighting the cop, and I says to myself, ‘Here is your chance, I give him one sock and he just sits down.” The Negro comrade smiles quietly, ex- hibiting two rows of magnificent white teeth. 23 ARE ARRESTED 3 The battle lasted for quite a while. Superintendent Black was hit with a bottle over his head, and received lacerations. The police be- came wild, but the comrades would not allow themselves to be fright- ened. The upshot was the arrest of 23 comrades, the first the police could lay their hands on. The po- lice had planned to put us all into patrol wagons and lock us up but they soon realized they would have their hands full all night long, and many of them would suffer. As it is, four policeman were taken to a -hospital. In the meantime the air in the hall became more tolerable and we all returned to our “night's lodg- ing.” ‘ EAN PY IT was a strange picture. Most of the chairs broken, their legs having been used as weapons. The floor—all covered with glass, rem- nants of broken bottles and shat~ tered window panes. Nearly all the window panes—colored too—bro- ken. The doors smashed and splin- tered. Perhaps three-quarters of the marchers had one injury or another—scratched faces, lacerated skulls, welts on back and hip. “ You come over to a comrade, and put your hand on his shoulder, only to see him writhing in pain; he had just received a blow over his shoulder. The doctor and the nurses, our W.LR. medical aid, had their hands full. Bandages, scis- sors, knives, blood—but what spirit! erybody happy in the knowledge: “We have stood our ground!” ‘Lhe gasses are still strong. Eyes are smarting; tears are running. Some- body says, “Don’t rub your eyes,” and the comrades let their tears flow freely—and thus they are talk- ing to each other, exchanging smiles and explanations while the tears are running down their faces. What a sight! Such a night ties comrades together with insoluble bonds. . AN ORGANIZED ARMY ' They had weathered the storm. They had showy the workers of Wilmington and of the whole coun- try that they were an organized army, a power, a collective body carrying out the will of a yet big- ger colleci:ve body—the working mass>s that had elected them to the Hunger March. ¥ The moment. required that we make clear to ourselves the ‘mean- ing of what happened. We discuss the situation in groups. The first question is: “Docs anybody regret? Is anybody frightened?” Not in the least. We feel, stronger than before. We have carried out our decision a hundred per cent. The second question: “Has the enemy won?” No, they haye lost. They didn’t expect such a counter-attack. ‘They didn’t appreciate the fighting workers. ‘The WHAT WAS THAT SONG? A STORY OF AN UNEMPLOYED WORKER By FRED R. MILLER (Copyright by Revolutionary Writers’ Federation) rs) INSTALMENT IT. THE STORY SO FAR—Previous instalments of “What Was That Song?” described the conversation between an unemployed worker an@ his wife who were about to be evicted. The worker has told her that the judge had given them five days to move; he then described his fruitless visit to the charities, and the demonstration for relicf outside. Return ing to his flat, the worker scrapes together the last bits of stale food. Now read on: . ‘The last thing I did was scratch off about a dozen oat flakes that was stuck to the inside bottom of the Quaker Oats box; I put them in’ my hand, and after pouring plenty of salt, and pepper on I gol- loped it up like it was a plate of ham and eggs. There was some coffee left in the pot, so I poured out a cup to wash the feed down with. It froze my teeth. I felt like smoking after that. The snipe wasn’t dry yet. I thought of the pipe on the mantelpiece and took it down. I didn’t have anything but ashes in it. For some reason I got the crazy idea of trying to smoke a pipe full of coffee. So I went, back to the cupboard, got the coffee bag, and then I knocked the ashes out of the pipe and loaded up with the ground coffee. ‘The first couple of pulls wasn’t bad. In a minute, though, the stuff began to stink like burning hair. I said out loud, “What the Jesus,” and made a beeline for the sink. ee next morning I was going to the station house for a bag of coal. It was like this. A plain- clothes bull came around to the house to investigate, see. He seen the old lady sitting there next to the stove with her coat on, so he tells me about'a load of coal just coming in from the Mayor's Com- mittee. He said every family that was registered at the station house could take away a hundred pounds of it. “You dust around there with a bag,” he says to me. “I’m going to put you down for an active case, so you'll be all set. They'll bring you a food check today or tomorrow, and every two weeks after that. By rights you ought’ to get a check “They Started Putting the Furniture Back.” © the old lady looked starved. ¥ says, “Before I go out, ain’t there anything left that we can put in hock? So’s youse two and the kid could have a couple of more meals, Can't tell when these cops’ll come through, all of that red tape.” Ellen says, “Only my coat. ‘The one with the fur. Maybe you could raise a buck or so on it.” I says, “Like hell, your coat. What're you going to wear in casé we get kicked out in the street? Your nightgown?” I banged the door shut and went out. Patek ee It was pretty windy outside. 1 had to put my hands in my pock- ets. I didn’t have anything to bring the coal home in, but 1 stopped in at the vegetable store up the street and got a loan of @ burlap bag. The wife used to buy most of her vegetables and stuff there when I was working, so the guy couldn’t turn me down for a nickel bag. Well I was going to the station house, like I started to tell you. I only went a short ways, and I was bending down to pick up a cigar snipe when I noticed a crowd, mostly kids, standing around in front of a tenement house. Some~ thing was up. I crossed over the street to see what was the matter, It was some old lady getting evicted. Two guys was carrying out her furniture and stacking it up on the pavement. She was sit- ting down on a bundle of clothes and crying. She must of ‘been pretty near as old as Ellen’s mother. I stayed there for a minute to watch her. A couple of women came over. One of them says ta the other, “Ah, ain’t it a shame? By QUIRT every week, but the Mayor's Com- mittze ain't giving us enough checks to go around. So we have to deal them out the best way we can. “And say,” he says, “I’m going to recommend you for financial aid, see? You owe three months’ rent —is that right? Well, I’m pretty sure the Committee won’t pay it all, but you can bank on getting a check out of them. Mightn’t be a whole lot; maybe say just enough to pay one month’s rent and a little over.” “You mean enough for us to move to another dump like this, huh?” I says. The kid was squawking in the front room. I could hear Ellen trying to calm it down, The squawks made me jumpy. eee The bull says, “Well, you know. ‘We ain’t supposed to advise no ten- ant to beat the landlord out of his back rent.” He give me a wink. “You know how it is. When they bring you the check, just use your own judgment.” “Sure, I get the idea,” I says. “But will this jack show up before we get kicked out, that’s the ques- tion.” ; “Oh, you'll get it all right. Don’t worry. Just keep your head out of the barrel, that’s the main thing. Everybody gets a bad break some- time. So long, uh, Harry.” i ida Yous got ready to go out. I went over to the sink and washed my hands. Then when I was wiping myself I happened to look in the looking glass and seen I needed a shave. The whiskers was so long they made me look like some Bol- shevik in the movies. But it was no use trying to shave with that blade I had. I got about fifty shaves out of that blade. It wouldn't pull out the hairs any more, let alone cut them. Ellen came in wh‘le I was put- ting my coat on, Both her and realize that it is possible to break the attacks of the police. A third question: “Will we allow our March on Washington to be interfered with?” “No. We coming every alfficul ty in our way. smart, but spirits are high. few comrades had been sent out quietly to learn the situation in the other lodging places. They come back with the information that both the garage and the Labor Lyceum had not been molested. The neighborhood around the church, on the other hand, is all aroused: There are groups of peo- ple in the street and the police is Putting an old tady like her out in the street in this weather.” The two guys had all of the fur= niture out in no time. There was a lot of people watching them, but they never paid any attention. A big beefy cop came out of the house and stood there on the stoop, looking down at the crowd. He moved over to let the two guys carry a little bureau down the steps. After they put it next to the other stuff, one of them took his hat off and wiped his forehead with the sleeve of his coat. I think he was the Marshal. “Wel) that’s that,” he says to the cop. “Where's that landlord hiding at, do you know?” Before the cop could say anye thing, everybody heard hollering down the street. We looked and scen a bunch of men coming along the pavement. ‘They wasn’t losing any time. The Marshal says, “Well, T'll be God damned. They're Reds, Til bet a dollar, Here’s where we have a@ battle.” The men piled right through the crowd and started to grab a hold of the furniture, You might of thought the cop wasn’t there, for all they cared. They says to us, “All right, comrades, Back into the house with it. Th'rd flor front.” \ The cop come off of the stoop, He shoves up to them and says, “What the hell do you think you're going to do?” et They says, “We're going to put this furniture back, that’s what", “Oh, no, you don't.” | “Come on, get out of the way," they says. | Well, while the flatfoot and the Marshal was trying to hold back | one bunch, three other guys runs into the house carrying some stuff. I Gidn’t sce where the Marshal's helper got to. The crowd began booing at the cop, saying it was a dirty shame to put an old lady oug in the street. Then it started. (CONCLUDED MONDAY) watching everywhere. The major part of the column ig untouched. Ths major part of the leadership is safe. We had telee phoned ~ Philadelphia and Baltic more to the representatives of the ILD. They are coming. They will take care of the prisoners, Our family is on the alert. It is way past midnight. The nurses have finished their work, The crowd is gradually overwhelm- ed with sleep. Only a few are awake Those are the older and most re« sponsible comrades. They are work+ ing out a plan for tomorrow. They are mobilizing the forces of the Hunger March for a new day of struggle. {