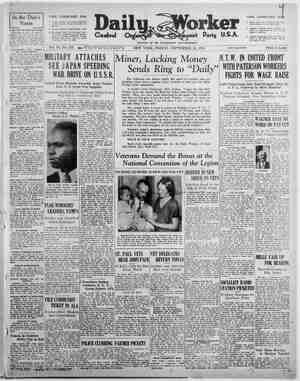

The Daily Worker Newspaper, September 16, 1932, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Daily, Worker ¥ o aily ex day, at 0 E. by the Comprodaily Publishing Co., Inc., daily exexept Sunday, E. Res New York City, N. ¥. Telephone ALgenquin 4-7956. Cable “DAIWORK. dress and mail eheeks to the Dally Worker, 50 E. 18th St., York, N. ¥. SUBSCRIPTION RATES: i$ hs, 2 By all everywhere: One year, $6; six months, APY ERuth of Maitiatian and Bronx, New York’ City. six months, $4.50. Reosevelt’s Farm Program HE democratic candidate for president relieved himself of two months, $1; exeepting Foreign: one year, $8; considerable wind from the State House steps at Topeka | on Wednesday, under the pretense of giving the farmers a “program.” But the kindest thing that even the New York Times, that eminent organ of finance capital and a Demo- Cen aee > rola th ” cratic party paper, could say about Roosevelt's program speech had to be accompanied by the following: farmers must have eagerly debated what » “Some things seem doubtful or at least ambiguous . . . “. . , not offering any concrete plan. . .” “did not suggest any icular method to make his program effectiv that may “program”? set forth in ce other things?) is made zation of the other five “points.” words of the first (that the “plan” must “not nulate f er production”) are either worthless words or, if not, they Il defeat the whole “plan.” t about > known for some time that Roosevelt was flirting with what is he “domestic allotment” plan, born in the brain of a cer- tain college y This “plan” aims to survey each farmer's pro- duction for the past five years and “allot” him certificates on his aver- age crop. For example, a farmer's average crop of wheat is 1,000 bushels, If he grows 1,200 bushels under Roosevelt's administration, 200 must be sold at the “world price,” but for the 1,00) bushels he gets the world price—plus the full or half the amount of the tariff on wheat, which is now 42 cents per bushel f This is the “plan” which Roosevelt is flirting with. And his Topeka speech was a “trial balloon” to see how it might be received. But he surrounds it with a barbed wire barricade of conditions. It “must not stimulate production.” But that is precisely what it will do, and to such a degree that it will make the whole “plan” collapse. His second condition is that it “must finance itself.” One of the most painful saibjects in the “domestic allotment” plan is—Who is going to pay? Who will pay these “certificates”? Which certificates, by the way, will be a rich source of discount robbery by the bankers who cash them for the farmers. And Roosevelt speaks for himself, but not for the farmers, when he says that “agriculture” does not want any ‘relief from the federal government. Third, Roosevelt says his “plan” must not result in “dumping.” dum will inevitably be the most marked result of the plan outside of the result that the small and middle farmers of America will be more impoverished by it than at present. Though their crops will grow just the same, they will be discriminated against in “allotments” in favor of the rich farmer, who will raise a big surplus because dumping will be so much velvet to him. Fourth, Roosevelt says his plan must be “decentralized.” This to avoid federal responsibility, though he wants the political credit for it and also to put its operation into the hands of the’local bankers, politicians and rich farmers. Fifth, it must “strengthen the cooperatives” (started as one of Hoover's pet ideas) which surely need “strengthening” both finan- cially and politically, since they are pretty much bankrupt and Iowa farmers who belong to them have seen their “cooperative” officials hiring gunmen with their money to beat them up and help the rich farmers scab. The sixth “point” is that the plan must be “as nearly as possible’— “volunt ” Anything is either voluntary or compulsory; and nothing can be “voluntary as nearly as possible.” Since the “plan” will help only the rich farmers and will injure the small and middle farmers, Roosevelt hesitates to say it will be compulsory, but if it is not compulsory and enforced by a dictatorship, it will not work at. all. Roosevelt’s further proposal, that “Federal credit” (denied by him to the farmers directly) “be extended to banks, insurance and loan com- panies” has the same bad smell as Hoover's “program” now being shown as no aid at all to impoverished farmers; and Roosevelt makes it certain by saying that these parasite bankers and other usurers shall be restricted in giving loans only to “sound mortgages. In short, helping the rich farmers who don’t need it, and refusing to loan.or extend loans to hard- pressed small and middle farmers. ear Roosevelt’s “farnr program” is only another trap to catch Tf it could possibly work—which it cannot in the long ould help only a small percentage of rich farmers and farm » and e the great masses of toiling farmers worse off this demagogy and deception, the Communist Party Yet * L told, “Emergency relief for the impoverished farmers without restrictions by the government and banks; exemption of impoverished farmers from taxation, and no forced collection of rents or debts.” ports the farmers in actual ve in life. It supports the g the “Holiday Movement” 1 farmers not only to vote the fb: action, and nd forecloseures, ti More Power to “Pioneer” ! By HELEN KAY Editor of “New Pioneer”, ig? well-known Jewish writer, Moishe Nadir, hearing of the critical situation in the NEW PIONEER, sent a liberal donation, to insure the appearance of the September issue and with it, wrote | Is anything wrong?” “I can't, by the way, help telling 2 you that T-consider the New Pio- | SUFFORT COMES IN | factor in the appearance of the August issue. For this reason thru- out the month hundreds of letters and post cards came into our office sent by our readers with the ques- tion “why didn’t the August issue of the New Pioneer come to me?” I've been waiting for it all month. neer » splendid magazine from the point of view of imbuing our work- ers’ kids with the class struggle idea. “I don’t know of any other red magazine of this kind that is edited with more care or is bet- ter illustrated and ornamented, or of one that comes nearer achieving what is set out to do So, here’s more power to the ‘New Pioneer, “ALWAYS READY” ‘The September issue is now off the press. A special school number, since the schools open on Septem- ber 10th, and with it the fight ior Free Food in the schools, the New Pioneer emanates the life of the workers’ children. From the lively cover, made by Juccb Burck to ta back strip, it breathes life, vivacity, and struggle. The New. Pioncer 1s a true Pic- neer. While it was forced to skip its August issue Cue to the fact that there was ro money, and that bills from the districts were due and not paid for, its appearance in September is a real comeback! ‘The New Pioneer promises its readers that as long as their sup- port is as keen and wide awake as it has been, it will continue to ap- pear regularly, and lead them in their fight for food and clothing. IN AUGUST we could not inform our readers through the mails that we were unable to appear. ‘This was due to the fact that the post office would have demanded Our young supporters in the cities and in the camps, hearing of our situation in various ways, rushed around and collected funds to in- sure the appearance of the Sep- tember issue. Frank Rallat, East Claridon, Ohio, sent the New Pio- neer a donation and said that he had worked for it. We wrote back immediately and asked him what work he had done. He answered: “You asked me how I earned the fifty cents. Well, I was driving a horse when he was holding the cultivator. We cultivated six acres of corn and a half an acre of po- tatoes and I get the New Pioneer every month.” From Bruce Crossings, Michigan, Pioneers write in from a territory where workers are starving: “We donate twenty-five cents for the Pioneer and challenge the Pioneers of Mass., Michigan, and Ironwood, Michigan, to do the same.” Here is a comment by Charles Yale Harrison, author of “Generals Die In Bed”, and other novels: “I wish to congratulate you on your splendid magazine. It is vital up- to-the-minute and breezy. It cer- tainly ranks with the best of the proletarian publications I have seen. I hope you succeed in raising your list of readers to 100,000. You merit success. My son asks me to tell you that the revolutionary ‘funnies’ on the back page are better than the ones he reads in the capitalist newspapers,” Adult workers, support the chil- dren! Subscribe for your child, for your friends’ child, for yourself, Spread, circulate, build the only at least $150 for our five thousand Recount wor hve een & big magazine for workers’ and farmers’ children, the New Pioneer, P. O. Box 28, Ste, D, New York. 1 White Chauvinism in Providence, R. I. By LORETTA STARR ‘HE struggle against white chau- vinist tendencies, both concealed and‘open, in the Party, was sharply dramatized by the famous Yokinen case. We still find, however, that our work among the Negro masses does not bring the results that we should attain. This is largely due to the lack of understanding of the Negro question and the failure of our comrades to root out white chauvinist tendencies from our ranks. Many comrades who are not in- volved in Negro work maintain that they are devoid of chauvin- istic tendencies. When drawn into Negro work, their concealed white chauvinism comes into the open. Such is the case in the Providence, R. 1, unit. During the Lucille Wright tour, | this sister of two of the Scottsboro boys was scheduled to speak in Providence. The Party unit was informed and asked to make ar- “producers of | rangements for this meeting. FIRST WRONG STEP At the unit meeting, the Party made a decision that one comrade | should visit a Negro worker who had dropped out of the Party. This Negro comrade was to prepare for the meeting, get @ hall, draw up a leaflet, and they, the Party, would help him give them out. This wrong attitude is typical of many units in connection with Ne- gro work. The idea that only Ne- gro comrades should be given Ne- gro work and the indifference and passivity on the part of our com- rades who allowed this to happen is the most prevalent expression of the influence of white chauvinism. Y¥.C.L. FIGHTS CHAUVINISM Seeing this incorrect an dindif- ferent attitude to the Lucille Wright meeting, the section of the Young Communist League ang adr. other Y. C. L. comrade fffed to form a united front with Negro and Cape Verdean workers. Prep- arations were made by these com- rades, a hall secured and leaflets printed. During the course of these preparations, a discussion arose on the Negro question, between a lead- ing Party comrade in this section and the Y¥.C.L. comrades. There this leading Party comrade made a statement which openly exposed his white chauvinistic tendencies: “Those ‘niggers” don’t want to be organized,” “They're too dumb,” ete. This brought about further discussion which involved other Party comrades. The chauvinistic tendencies which have so long been concealed were expressed in statements such as: “The Party is on its knees to the Negro workers, flinging arms around their necks in its desire to keep them in {ts ranks”; insinuating that the Negroes are inferior be- cause “their brains are smaller than the white”; “No special at- tention should be paid to the Ne- gro workers; they are exploited more than the white workers and should realize who their enemies are.” This was followed up with white chauvinist bourgeois talk about sex. “PRACTICAL” POISON At the next Party meeting, the unit decided that they could not raise the deposit on the hall. Their excuse was that in the first place the Scottsboro meeting would be a flop, anyway. To save money, their suggestion was that Lucille Wright should speak on a street corner. -No arguments could con-" vince them otherwise. They said they were not white chauvinists. They were only “being practical.” When it was pointed out that their statements and their attitude towards the Scottsboro meeting were clear-cut white chauvinism | the comrades denied it. It is clear that the comrades who made these statements do not think themselves chauvinist. They prepare for Ford’s meeting”; “I was angry when I called them nig- gers.” SOCIALIST PARTY POISON Not. one comrade could give any facts or examples to prove any of their statements. No Stientist has ever proved the slightest inferiority of Negro to white. The Party is not “on its knees” to the Negroes. This is the most vicious kind of Socialist Party propaganda. Our Party, which is a Party of Negro and white, does state, however, that special atetntion must be paid to work among the most oppressed Negro masses. ‘The Negro masses have a justi- fied mistrust of the white work- ers because they have been op- pressed, misled and betrayed by the white master class ‘and by such fakers as the Republican and Democratic politicians, the A. F. of L., the N, A. A. C. P., the Social- ist Party, other reformists, etc. Though we are the only Party fighting for Negro rights, we, as yet, have not proved to the Negro workers in Rhode Island that we are sincere and that together we can better their conditions. That is why we must pay more attention to the Negro masses. To say that one was angry is not enough to cover over a state~ ment so contradictory to the Party Bne. One is not a chauvinist for just a moment; the remark was an outburst of concealed chauvinism, UNIT CONDEMNED Some comrades in the Providence Unit are allowing capitalist views to influence them. These views have to be condemned as anti- working class, as views that strengthen the capitalist oppression of the Negro workers, “The Negro masses know every- thing that goes on in our Party | that relates to the Negro question. It is not possible for us to extend our political influence among them, except upon the basis of daily, con- tinuous, uncompromising, relentless war, against every manifastation of white chauvinism.” (Eary Browder in April “Communist.”) “_E-R-R-- I'd make as good a president as Hoover or Roosevelt” WORK, NV run, rns, OL EAI 10; 10a By J. BURCK. cers NEC roosevert, Ft ADs rh: BUR, oe Guns and Rope for NegroesWho Fight for Their Right to Vote By ELIZABETH LAWSON Ee hundred Negro citizens of Shreveport, La., approacheg the doors of the Lakeside Auditorium not very many weeks ago, prepared to hold a meeting in which they would plan to cast their ballots. ‘They were, in the overwhelmingly majority, followers of the Demo- cratic Party. These Negro citizens found the augitorium guarded like a fortress. P&ce, armed with rifles and ma- chine guns, stood sentinel at every | door. ‘The meeting was broken up. | “¢mocratic right, the ballot. | most two-thirds of the American- Albert White, editor of the Shreve- port Afro-American, who was to be @ speaker at the meeting, was driven out of town and forced to remain in hiding for many weeks. Said the police: “Before Negroes are allowed to vote, the streets of this city will run red with blood.” “WE DON’T WANT YOU TO VOTE!” At about the same time in Hous- , ton, Tex., C. N. Love, editor of the Houston Informer, who had also. been active in the fight for the suffrage, awoke at midnight with the smell of fire in his nostrils, He found that slabs of wood saturated in oil had been pulled around and under the house, and lighted. A short time later, at Denison, | Texas, leaflets were distributed in “T helped | Hashes, ® Negro, on the court-house steps in Sherman, seven the name of the Klan. .They read: “Negro: the white people do not want you to vote Saturday. P “Do not make the Ku Klux Klan take a hand. “Do you remember what hap- pened two years ago, May 92” (This | | 4,000,000 Negroes Now Barred from the Polls refers to the date when George Hughes, a Negro, was burned alive at Sherman.) . * . UR million Negro citizens of the United States are today de- prived of that most elementary Al- born Negroes 21 years of age and over, are disfranchised, In ten states of the Union and the District of Columbia, the na- tion’s capital Negro citizens ‘are today barred from the polls. The area of disfranchisement covers an immense territory of the South— including the states of North and South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Virginia, Ar- kansas, Louisiana and Texas. It is through these states that the Black Belt runs—that great territory in which the majority of the popula- tion is Negro, SHARE CROPPERS, TENANTS RESISTING This year, the struggle has sharp- ened. The increasing unity of Negro and white workers, the struggles in the South, the resist- ance of Negro croppers and tenants against robbery and peonage—these have struck terror into the hearts of the white robber landlords, bankers, bosses and state officials. Their furious efforts to continue NEGRO The White People Do Not Want You To Vote Saturday Do Not Make The Ku Klux Klan Take A Hand ===: Do You Remember What Hap- pened Two Years Ago May 9th? AND THE N, A. A, C. P. SAYS IT WON A VICTORY IN TEXAS!— ‘This is a copy of a leaflet scattered by the Ku Klux Klan in Denison, ‘Texas, several weeks ago, just before the Democratic primary elections, The last pargraph refers to the lynching on May 9, 1930, of George and extend the disfranchisement of Negroes is one of their ways of trying to fight back the wave of resistance, Peer ee ¥ what methods are the Negro citizens disfranchised? First, high poll taxés, and the requirement that all personal taxes be paid before registration. In Georgia, all taxes legally required since 1877 must be paid six months before election. Picture the poverty-stricken Negro worker or tenant-farmer, deliberately kept on the verge of starvation, being able to meet these requirements. Second, a high property quali- fication, Third, a fake “educational test,” whose only purpose is the dis- franchisement of Negroes. No Negro will ever be able to read to the “satisfaction” of the lily-white committeemen or poll-watchers of | the South. Fourth, an “understanding and | character” test. But obviously, a | Negro who wants to exercise his | right of suffrage thereby becomes | an “undesirable citizen” in the eyes of the poll-watchers, Fifth, the famous “grandfather” clauses, which operate to permit persons to vote even when they are | not able to meet other tests, or their ancestors, provided they voted in 1867. The lily-white purpose of | this clause is obvous, Sixth, sheer terror—the use of armed force, by police, sheriffs and militia; the threat of lynching; the stirring up by the white press and other boss agencies of crowds of white hoodlums against would-be Negro voters. ‘ SOME RECENT EXAMPLES Here are the some recent ex- amples from the field of struggle for the suffrage: North Carolina: Negroes of Ra- leigh who were unable to pronounce words in the state constitution or explain them to the “satisfaction” of the poll-watchers, were stricken from the lists. Two hundred and ten colored Democrats were de- prived of their ballot in this way. In other North Carolina localities, a last-minute challenge to Negro voters—so late that there was no time to answer it—resulted in the disqualification of over 1,400 Ne- groes. No whites were challenged. Tennessee: The state convention of the Democratic Party did not pass a proferred resolution against the franchise for the Negroes, because’ it “would be inefficious” —that is, it wouldn't work, But ‘terror and intimidation were used to try to keep the Negroes from the polls. Former Governor Paterson, now once more a can- didate for the governorship, said: “It is a travesty upon law and decency to allow the votes of these Negroes to determine ‘the result of a Democratic primary.” Paterrson is being urged in the campaign as. “the white man’s choice.” Texas: In Houston, election judges refusing to admit Negroes to the polls were backed up by the police. At Sherman, a flaming cross warned Negroes in the name of the Klan to keep.away from the voting booths. South Carolina: Democratic com- mitteemen invoked the grandfather clause to strike from the lists the names of Negro citizens. i . 8 8 8 by one method and another, millions of Negro citizens are deprived of one of their elementary INSTALMENT I kloverdale, penn. “dear comrade do you still re- member johngavro from valar i only got three weeks for it and this is the eighth week that’im out at kloverdale and im writing i greet you comrade and all the communists, johngavro member of the communist party Clie HY, of course I remember John Gavyro from Volar. A summer storm greeted me when I stepped off the train about noon, at the Valar station, I was told that the section had informed the miners’ committee that they were sending someone out here today, but there was no one waiting for me at the station. I thought that it might be because of the storm. Hardly waiting for the sun to come out, I started for the camp. Leav- ing the shopping district, I passed over a little bridge into the camp of the miners. In times of strike, it is not ad- visable to inquire regarding the whereabouts of the miners, because it is likely that one may bump into @ spy, and then the company’s gangsters will know that one is in town before it is desirable. If the worst happens one will immediately find oneself either in jail or in the hospital. So, on the alert, but not looking too much to the right or left, I went through the town, MEET JOHN GAVRO Suddenly Hungarian words struck my ear. Ten or a dozen Hungarian, mners, sitting on chairs and bench- es on the stoop in front of a store were talking. A young giant, well over six feet, with mustache and clean-shaven cheeks—as I later found out, this was John Gavro— was just explaining how, in his sailor days, a machinist was shot down by the officers because he stood up for a Negro stoker. “Well,” I thought, “judging by this, I'm on the right track.” I went over to them ang told them where I was heading. The district had sent me out be- cause for the last three days, since the arrest of the strike leaders, there had been no news of the miners. One by one, they shook my hand warmly. I grabbed John Gavro's big palm with both my hands. I sat down to talk with them for a while, and then we quickly sep- arated to call the miners together on the empty lot behind the relief kitchen, for a meeting. They ar- ranged among themselves where each one was to go, and they part- ed. Only Gavro stayed with me and the storekeeper. iu “NO PLACE TO GO” J" “T have no place to go now, and I can’t call anybody because I’m living in the company district among the strike breakers, mostly Poles and Negroes. They just pick- ed them up and brought them here from the Chicago garbage heaps. They all look it. There isn’t a single miner among them. “My landlord is a company man, but his wife is Hungarian.” He said this hesitatingly, and when he mentioned the woman, he turned his eyes away like a school- boy. The storekeeper winked at me and I understood. In spte of the fact that John Gavré was on strike, his landlady did not kick him out of the company’s house, because . . . “Because, you know, she is Hun- g@arian, and I’m.Hungarian too,” John tried to explain, but the store- keeper laughed, at which Gavro said: “Well, what of it! I’m not home all day, and I don’t eat a single bite over there even though the woman offers it to me! And I don’t even see the strike breakers. I go home in the evening and I leave at dawn. Where else could I sleep? I haven't money even for cigarettes. In the morning there’s the black coffee with a little piece of bread from the relief kitchen. If there’s some kind of slop for supper, we are lucky, but most of the time, there isn’t even that.” JOHN GAVRO A STORY OF MINERS’ LIVES AND STRUGGLES By EMIRY BALINT. ONLY BREAD AND COFFEE. “There Has been no supper for two days now, and today only the kids got bread with their coffee,” interrupter the storekeeper, The storekeeper, to show me his poverty, led me into his store and pointed at the empty shelves. He explained that, actually, he was a miner, that now he was striking too, arid that he only kept this little store on the side. He had no money to buy stock, and except for a few packages of cigarettes, there was hardly anything in this store, “Why should I keep any stock?” he explained, “no one has any money to buy with. They even get the cigarettes one at a time tor a penny apiece...” When we came out, John Gayro was no longer in front of the store, The storekeeper said that he must have got to feeling ashamed be- cause of the woman. “WHAT A MAN JOHN IS” “But what a man John is!” he said. “He would not miss the picke et line for anything. He can harde ly move his bulk, he’s so hungry; nevertheless, he walks six miles there. Packet for one hour, and then six miles back, and here he gets a cup of black coffee with the rest. Today we had no bread either. He used to mine twice as much as any ordinary man, and he could lift a two hundred pound potato barrel like a bottle of beer. That's the kind of a man he was. All the same, I wouldn't like to take a wal- lop from him today either. ... That , Woman is his ruin. She was al- ways a rotten one She doesn’t care whether it’s a Pole, Gypsy, or Ne- gro If the miner has any money left, she takes it away at cards or for whiskey. That’s why she keeps the strike breakers in the house. ; “That's the kind of woman she is...” 3 “Well, if he likes the woman—” I interrupted. “I don’t know. I only know that these single miners are like mon- grel dogs. It’s hard for them to leave the door where they get a bone.” ig ae hee ht the strikers gathered on the lot behind the kitchen. Men, women, children. Blacks, whites, There were those who had hurried up pantingly inquiring after the provision truck. One or two women had come-with pots. The children began to“blnbber when they heard s a popeetanrepanenpso tan ante r eat Twenty or thirty miners were buzz- ing around me, each one trying to push the other away so to be the one to tell me their troubles. “The mine is operating with strike breakers. Formerly, four hundred of us were working, now only two hundred and fifty. True, about a hundred of that number are = w, but the rest, we are sorry to say, are from among us. We came out a hundred per cent five weeks ago, but the miners are so poor around here, that if they come out in the morning, in the evening they are already asking for relief. So, one by one, most of them have gone back.” (To Be Continued) McNamara By HENRY GEORGE WEISS Because he was strong and fearless Tn Labor's behalf They have caged him here, Yet he has grown stronger In their brison of stone and stecl, ‘The labor-fakers have dropped away. The tools of corrupt politics Whom his martyrdom saved Heed him no longer. They are afraid of such men, Afraid of their sublime courage, Proletarian strength. In the grey light of prison depths He looms a A Prometheus it, und to a rock For daring to light the torch of Freedom At the fires of rebellion. democratic rights, as part and par- cel of the struggle of the white bosses to keep them apart from the white workers, to maintain them as a spedlally exploited group. White workers are also dis- franchised—to a greater extent this year than ever before. The for- eign-born, the soldiers and sailors, the youth, are disfranchised by law. An enormons percentage of the unémployed are disfranchised in fact, by residence qualifications, by poll taxes, by property-require- beeen ete., ete. Ree necessary against, disfranchisement of the work- the ers, black and white, But we must never forget—while a certain ‘centage of white workers are dee prived of the right to vote, the Ne« groes in the South are deprived the ballot—almost to a man. ‘This national aspect of the problem, should never be lost from sight, In another article to be published soon, I shall show how the Repub- lican, Democratic and Socialist parties have combined to deprive the Negroes of the South of the right of the ballot, and I shall take up the question: What is the duty of the Communist Party and of the revolut 3 Q I)