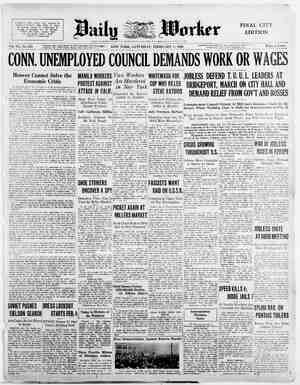

The Daily Worker Newspaper, February 1, 1930, Page 6

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Central Organ of the € \ Published by the Comprodaily Frvisning Co., Inc., dafty, except Sunday, at 26-28 Union Page Four Square York City, Y. Telephone Stuyvesant 1696-7-8. Cable: “DAIWORK.” Address ll ¢ to the Daily Worker. -28 Union Square, New York, N, Y. ——————— Sas ee: <a By LOUIS KOVESS. ICHAEL KAROLYI, first E Hungarian “People’s R touring the Ur ,weeks, During meetings, mai gave interviews. / and criticise his ideas, his speeches and wr The Background of Karolyi’s Certain remarks of Karoly meetings make us think that his tivities are aimed not so much m (that is his regime) only ng classes may be thankful!” Question—He stated that today he 1ot_ accept his former land reform pro- ause “he wants such a solution of ion, which will leave the land- rs without land.” n dictatorship—It is his opinion tha rian dictatorship could not stand in Hungary.” Concerning proletarian dictator- ship in ‘the Soviet Union, he states that the fall of the proletarian dictatorship in the Soviet te iese permit s he expressed Tour. workers tp underst ans Union would be followed by an unprecedently starvation, oppres: severe capitalist dictatorship. sed-it, but mainly de: On Fascism and Anti-Fagcism—He states that fi and the sm is an international phenomenon, gary. Conditions in H n ght against it must be based on the ed up with that of background of his An pr ariat and must be of an international In the growin te: He states he is an anti-fascist. He capitalism, we are ‘I am not a Communist and I am not a Beanie ig Hen cary l-democrat. I am a 100 per cent social- with.a political ¢ He explained later meetings that he fascism. There is ans he is an anti ist. ployed Pan Europa—He stated he proposes imperial- c irredentism. for a ype on a soci On War. police. “United trial and and mas letariat to list. basis. Ss he is opposed to imper- n is an element of war dan- Eu rutal oppression ani of their standard of alization drive, in capital, is being carried clusively by speed-up. cial-fascist methods with m and in ¢ keener foreign down of the to the production, as a resul tion, speed-up increases unem) the standard of living of ‘al proletari Th re es to the offensive. \ Criticism of Karolyi. will keep to the anti-fascist li tently than he did up to now, | his line would be that given by the Berlin | His expression “socialist” places him in the position of a left reformist, as so- cialism can start to develop only under condi- of proletarian dictatorship and he is op- posed to proletarian dictatorship. His “social- urope”’ is meaningless, as one must choose between a_ social-fascist controlled Europe, which would be a combination of capitalist compe home ma mi ployment of fascist oppression countries for imperialist war and counter-revo- cist demagogy to check the revolt lutionary war against the Soviet Union, under velopment; multiplication of the imper fascist leadership, or European Soviet irredentist propaganda for “a Great Hung and at the same time increas! making a pact with Roumania, this propaganda is “Little Entente,” but The irredentist dem. posed. It is quite oy Bethlen government, of “Great Hungary war against the Little I for Hungary’s participation in the Union war ide w imperialist blo If Karolyi has in mind, that after the fall the of Horthy regime a new “democratic” regime may come, he is mistaken. The destruc- tion of the remnants of feudalism is not the ga task of a new bourgeois democratic revolution, k the task of the coming proletarian revolu- In its onward march it will sweep away The rose of the an October (emblem of Karolyism) has The time for bourgecis revolutions is . This is the period of ptoletarian revolu- tions. The new revolution in Hungary will not tart, the Hungarian October started: It will start, where the Hungarian Commune left it, er hed by the experiences of the Russian October, the 12 years of the Union of Social- ist Soviet Republics. Only the proletarian dictatorship can solve the land question. Only a clear proletarian revolutionary line can lead the fight against the danger of imperialist war and for the the Bri war. wor i keeps n pro elopme s uitered meet- n this belief. his position on differ them: He Now let tions as he Social Democ oppositior social-demor I cluded with ent ques- said he arian sec ” becau he Horthy regime. acy He re- it fused to speak “under the augpices” of the defer of the Soviet Union, which is a task Rand School. At the New York m of every true anti-fascist. of the An’ orthy League he accepted the | en if nobody expects that Karolyi will opposed but to time realize the historical necessity of the proletar- ian dictatorship as the transition of true social- ism, he must throw overboard, at least, every- thing that is contradictory to the program of the Berlin International Anti-Fascist Congress. y. An anti-fascist can not have two sets of ideas. n, révolution with the wor not only to, Hungarian i i neral n social-democracy i —At a mass meeting in Lor Ohio he still uttered words lauding ce phases of hi But at later meetings in Cleveland, Pitisburgh and New York he stated he does not stand on his former plat- His non-anti-fascist utterances will be severely cr sed and condemned by the workers, who especially in this period of crisis and sharp class struggles want to know, who is who and what he stands for! ae: Unemployment and Misery Grow Among Illinois Miners They know they can’t depend upon it to fight their battles for them. They are turning to the new union and to the leadership of the Communist Party. The National Miners’ Union has proved to the miners of southern Illinois that it is a fighting union. Where the National Miners’ Union leads a strike it is a militant strike— not a vacation. In the days of the U. M. W. A. iners in s a rich of prosper- rying to convince the r ‘Southern Illinois that Am country and that this is a pe ity. They will point to their u ragged children. The will show miserable homes. They will set be: IT is no use t Jernourish their you t at all) that is composed of potatoe and black coffee. And they will ask, “Is this prosyerity ?” | picket lines were almost unknown—strikes © They are starving. Even the miners that | Were vacations during the slack season in the have -had work during what is supposed to be coal industry. ‘The miners sat home; the mon the busiest mining season in the year are no officials eon bunsed they Desceral luxurious better off. Everyone of them owes the com- life, hobnobbing with the social elect of the Mice. store: from $800 to $500; Many never | bourgeoisie and when the slack season was Gisiwaonéy’ on: pay. day: they get only script | oer the miners returned to work and were which is redeemed at the store for food and | fortunate if the new contract included a few supplies on credit. Script is worth only 89 eae jin their favor. Under . the National Mesiaon the deliat, ‘Thevzuiner: pays 11 per. | ners Union militant picket lines are thrown cent interest for the privilege of trading at | around the Reema Beciahsottes of strikers sre ear iiany store, from mine to mine spreading the strike, the leaders of the union are in the thick of the fight, facing the guns of the militia and the clubs of the police and the deputies of the U. M. W. A. The National Miners’ Union is a fighting union and the miners know that the Communists are playing a leading role in it. There was a time when the cry that Commu- nists are running the N. M. U. had some in-~ fluence, was able to confuse some of the work- ° ers—terrorize them away from the union. Now that time is past. The miners answer Oh, there is prosperity in Southern Illinois. No one can deny that. Illinois is a rich ter- Titory. v oiee coal harons live in Illinois. Some of the fnines are the richest in the country. The operators have plenty of prosperity. Since | the machines went into the mines they have been able to produce more coal at a lower cost of production. They have not had to use so | many men. They laid off thousands and di- | vided the time and work between those that — remained. Full time work now means only | the cry with, “If that is the kind of a fight ‘ about three days a week and even this is un- | the Communists put up—I’m for the Commu- | usual. Fat, beautifully clothed children par- | nists!” ade the streets of the larger towns with their In spite of the terrorism that has been used nurses. Beautiful stone mansions grace and | against members of the N. M. U., in spite of beautify somé of the towns. There are three | the raids and expulsions and threats of depor- and four car garages for families of two and | tation the influence of the N. M. U. and the three people and these cars are housed in a | Communist Party is growing daily among the manner that no miner is able to house his | miners, The next few months will see large | children. Sure, there is prosperity in south-. numbers of miners coming into the Party and - ern Tlinois—but not among the coal miners. the League. Dope Peddelers Flustered SHANGHAI—The Christian missionaries in China, being inherently somewhat below normal intelligence, are in a flutter at the growing mass anger against their further hold- ing special privileges and the rumor that the British are to agree that such privileges be | ended. While they have loyally served as cul- . tural agents of imperialism, cold-blooded busi- | ness men at times think the special privileges . of missionaries hurt business by provoking ; anger of the masses leading to boycotts. If there is any agreement to end their privileges, it will be in the interest of imperialism, and | since they loyally support*it, they have no kick coming. & But there are some thiffgs that you can tell | these miners and that these miners can tell | wu even better. They can tell you that since the operators put in conveyors and machines hundreds of thousands of miners have lost ‘their jobs and the rest are working part time. They can tell you that one man is now doing work of four and five men. They can tell ‘vou that the pace at which the youth works jin the mines today the average young worker li be old and worn out before they are can tell you that the United Mine of America is no longer a union fight- i’ the interests of the miners but a com- nion—a strikebreaking agency that re- force every attempt of the miners a militant fight agaifist the bosses. Slavery on the Job—Starvation Without It! * Baily [2: Worker | Party of the U.S. A. By Mali (in New York City only): $8.00 a year; By Maii (outside of New York City): $6.00 a year; SUBSCRIPTION RATES: $4.50 six months; $3.50 six months: $2.50 three months $2.00 three months By Fred Ellis A Month in the Ohio Pen By TOM JOHNSON. gs aoe toughest joint in the country to pull time in.” That is what the old timers with the scars of half dozen pens seared deep in their grey faces, tell you when you first pull into the Ohio State Penitentiary at Columbus. And take it from ont who knows, they are not far wrong. Charlie Guynn and I were brought down from Belmont County on December 18th to do 5 to 10 years in the Ohio Penn, for the crime of being Communists and attempting to hold a | demonstration against war in Martins Ferr last August. Warden Thomas, a typical prod- uct of capitalism’s penal system himself, met us at the big gate. “Boys,” he said, “I want to give you a tip before you go in. You have political ideas different than mine and different than most of us have. If you are wise you'll keep them to yourselves. If you start any agitation in here you'll damn soon find out that we can get pretty tough. Also there are over 600 ex- | service men in here, and if you talk against the government in here one of them may take a notion to punch you in the nose. That’s all.” Such was our introduction to the Ohio Peni- tentiary. We were immediately separated, and that night as I marched to my cell I found that | 83 ex-soldiers had been assigned me as cell mates. As soon as we were locked in our little 12 by 14 cell, one of my cell mates told me that he and the other two boys had been called down to the Deputy Warden’s office the day before and told that they were to cell with a wild Bol- shevik, and that they were to do their best to show me the error of my ways and to “Amer- icanize’ me. Quite evidently the “punch on the nose” was to come early if the Warden could maneuver it. - . Unfortunately for the Warden’s plans for my “Americanization,” my ex-soldier cell mates, two of them wounded in France, and then kick- ed out of the army with less than $100 each and no job in sight, had* been thoroly disillu- sioned with American “prosperity.” In no time at all, these boys, at the same time products > cand victims of capitalist exploitation, were ask- ing me if the Communist Party would accept them as members on their release from prison. “A punch on the noge,” the Warden had said. I doubt if any ver ever had the “unquestioned sympathy and admiration of the other prisoners which Charlie and I had. Our first. week behind the walls saw us receive close to a score of ‘notes—“kites” they are called in. prison °slang—from fellow convicts, con- gratulating us on our fight against. American capitalism and pledging solidarity in the fight. And each one.f’ these notes. was “passed or delivered to use at the ‘risk of the writer or those who deliveréd it, being thrown in the “hole” (solitary confinement. in the dun- geon on bread and water) for a week or more, if they were caught. Gifts of tobacco (a pre- cious commodity in prison) magazines, etc., came to us unsolicited. F And small wonder that the best of the pris- oners were with us. Most of them workers, if their experiences on the outside had not in- stilled in them a hatred for the capitalist social system, the brutal treatment within the walls completed the process, For brutality is the key-note of the Ohio Penitentiary. Guards speak only to curse, and as often as not to brutally club into unconsciousness some luck- less convict who has been guilty of the most minor infraction of prison rules. On the othexshand, if you are caught taking | the next morning when court convenes. an extra piece of bread at the table, smoking in your bunk, out of step in line, or doing any of a hundred things the authorities have de- ereed you may not do, the guard may prefer to turn you over to the tender mercies of the prison court. ‘ A real parody on justice, this prison court. The usual procedure is reversed. You are punished first and then tried. You may try to sneak a piece of bread off the table at break- fast to help fill that void that you are sure to feel before noon on prison fare. The guard 's it or thinks he de: He calls you out and takes you over to the “hole.’ Here he strips you downto the overalls and underwear, makes sure you have no tobacco with you, and places-you in an ingenious instrument of tor- ture. This is a narrow cage of iron bars, measuring about 214 by 2% feet and 6 feet high, which is attacked to the inside of the dungeon door. Once in-this cage there you remain, unable to lie down or sit, forced to stand up right. If you are unfortunate enough to have to perform any of the normal bodily functions while in the cage- it is as my cell mate expressed it, “just too bad for you and your overa both.” There you stand until Then you are taken out and brought before the Dep- uty Warden for trial. He may find you guilty, and back you go to the hole for another day or more. He may find you not guilty, in which case off you go innocent and with your record clean, but with the scars of the cage still on your innocent back. This brutal treatment, together with the féar- ful monotony of prison life, breaks men down, ages them, kills them in time. Day after day the same drab routine goes on. Up in the morning, march to breakfast, then march to work in the knitting mill. At night march to supper and then march back to be locked up in the cell. This was our routine, day after day. At night in the cell read magazines until nine and then to bed. I say “read magazines.” We brought in with us some revolutionary books with the hope of doing. a bit of studying “Not these books,” said the Deputy Warden, as he took from us the three volumes of “Capi- tal’ and our other books. Not even a scrap of paper to write on would they allow us. Even under Czarism some differentiation was : made between ordinary criminals and. political - prisoners. But not in America, Here the poli- tical prisoner is thrown in with the worst scum of the underworld. Foréed) to’asso¢iate with | degenerates, with diseased.men.”.A, syhiliptie - cell mate is a common oceurrenée,”No radical | literature is allowed: « Even thé,Daily Worker is barred at the Ohio Penitentiary.’ No food, no tobacco, is allowed to each’ the political prisoner from the outside...Far from being better treated the Communist is the subject for the worst brutality of debased and degenerate guards, anxious to gain the approbation of an ignorant and reactionary Warden. Such is the Ohio State Penitentiary. Today Charlie Guynn and I are free after a month behind those gray walls. Lil Andrews has been reelased from the womens reformatory at Marysville, where conditions are even worse. We have been released on $5,000 bond each pending action by the Court of Appeals. Will we go back in May to complete our ten-year terms or will we remain on the outside, fight- ing in the front ranks of the Ohio working | class? The answer to this question depends solely on the workers of Ohio. Their mass power expressed in revolutionary action can alone protect us from the.vengeance of the ruling class, ‘ THE SOCIALIST TRANSFOR: - MATION OF THE SOVIET VILLAGE By J. STALIN. The following is the second installment of the text of the speech delivered by Comrade Stalin at the Congress of the Marxist Agra- rian Research, on 27th of December, 1929. —Editor. ae . (Continued) 3. The Theory of the “Tenacity” of the Indi- vidual Small Peasant Farm. Now to the third prejudice in political econ- omy, the theory of the “tenacity” of small peasant economy. The objections raised by bourgeois political economy against Marx’s well known thesis on the advantages of large- scale undertakings over small, which these economists consider to apply to industry only, and not to agriculture, are well known. Social democratic theoreticians of the stamp of David and Herz, when defending this theory, have sought to “base” their arguments on the fact that the small peasant is enduring and patient, that he is ready to bear every deprivation in defense of his plot of round, and that in the struggle against larg®-scale agricultural un- dertakings the small peasant farmer evinces the utmost tenacity.. It is not difficult to grasp that such a “tenacity” is worse than any irresolution. It is not difficult to grasp that this anti-Marxist theory pursues one sole aim: to eulogise and strengthen the capitalist order. It is precisely because this theory pur- sues this aim that it has been so easy for the Marxists to shatter it. This is not what con- cerns us at present, but the fact that our actual practice, our reality, is supplying us with fresh arguments against this theory; but our theoreticians, strangely enough, either will not or cannot make use of this new weapon against the enemies of the working class. I refer to our practical experience gained in the abolition of the private ownership of land, in the nationalization of the soil, in the practical lib- eration of the small peasant from his slavish attachment to his patch of soil, by which we have facilitated for him the transiton to the paths of collectivism. What has in reality fettered, and continues to fetter, the small peasant of Western Europe to his small commodity economics? Above all and mainly the fact that he owns his piece of ground, the fact of the private ownership of land. He has saved for years in order to buy a piece of land; he has bought it, and now, comprehensively enough, he does not want to part from it; he will endure anything, suffer the greatest deprivations, live like a savage, in order to retain his piece of land, the basis of his individual economy. Can it be maintained that this factor will continue to exercise this effect under the conditions given by the Soviet system? No, this cannot be maintained. It can- not be maintained, for with us there is no pri- vate ownership of land. And since with wu there is no private ownership of land, for this very reason there is no such slavish attach- ment to land among us as may be observed in the peasants of the West. And this fact is bound to facilitate the transition of the small peasant farm into the system of the collective | undertaking. This is one of the reasons why the large-scale undertaking in the village, the collective farm, is able to demonstrate with such ease in Russia its advantages, as com- pared with the small peasant farm, under the conditions given by nationalized land. Here lies the great revolutionary importance of our agrarian laws, which have cancelled absolute rent, abolished the private ownership of land, aml nationalized land. This places an argu- ment at our disposal against those bourgeois economists who proclaim the tenacity of the small farmers in their struggle against the large-scale undertaking: Why is this new argu- ment not sufficiently utilized by our agrarian theoreticians in their struggle against all bour- geois theories? When carrying out the nationalization of the land, we follow, inter alia, the theoretical as- sumptions given in the third volume of “Cap- ital,” in the “Theories of Surplus Value,” and in Lenin’s well-known agrarian theoretical works, which represent an extremely rich treas- ury of theoretical thought. I refer especially to the theory of ground rents and in particular to the theory of the absolute rent. It is now clear to everyone that the theoretical asser- tions made in these works have been brilliantly | confirmed by the actual practice of our social- ist reconstruction in town and country. Only it is incomprehensible why our press should be thrown open to the unscientific theories of such “Soviet” economists as Chayapov, whilst the works of genius of Marx and Engels, deal- ing with ground rents and the absolute ground rent, are not popularized and brought into the foreground, but lie hidden under a bushel. You will of course recollect the care and deliberation with which Engels treats of the question of the transition of the small peas- antry to the system of socialized economy, of the collective farm. In his essay on “The Peasant Question in France and Germany,” Engels writes: * “We stand decisively on the side of the small peasant; we shall do everything per- missible to render his lot more bearable, to facilitate his transition to the copera- tive should he decide in favor of this, and even should he not yet be able to come to the decision, to make it possible for him to have a longer period for consideration on his piece of land.” We observe the circumspection with which Engels approaches the question of the transi- tion of the individual peasant farm onto the path of collectivism. What is the explanation of a circumspection which at a first glance ap- pears exaggerated? What was his point of densrture? Obviously it was the fact of the existence of the private ownership of land, the tact that the peasant possesses his patch of soil and will not part with it easily. This is the peasant of the West. This is the peasant of the capitalist countries, in which the private ownership of land rules. It is comprehensible that here the matter must be approached care- | fully. Can it be maintained that such a situation as this exists in the Soviet Union? No, this cannot be maintained. And it cannot be main- tained for the reason that we have no private Rie ieee of land chaining the peasant to his individual farm, It cannot be maintained for the reason that our land is nationalized, smoo- thing the way of transition from the individual peasant farm to the collective. This is one of the reasons of the comparative ease and rap- idity with which the collective movement has developed among us of late. It is regrettable that up to the present our agrarian theoreti- cians have not yet attempted to draw a clear line showing this difference between the posi- tion of the peasantry in the Soviet Union and in the West. Work in this direction in the West would be of the utmost importance, not | only for us Soviet workers, but for the Com- munists of all countries. It is not a matter of indifference for the proletarian revolution in | the capitalist countries whether socialism will have to be built up there, from the first day of the seizure of power by the proletariat, on the foundation of the nationalization of the land, or without this foundation. In my latest article: “The Year of the Great Change,” I brought forward the well known | arguments on the advantages of the large- scale agricultural undertaking as compared with the individual farm, referring thereby to the Soviet farms. It need not be proved that all these arguments apply equally to the col- lective farms as large economic units. I speak here not only of the advanced collective farms working on a mechanical and tractor basis, but at the same time of the primitive collective undertaking representing, so to speak, the manufacture period of collective economic construction, and working with the accesso: of the peasant farm. I refer to those primi- tive collective farms being formed atthe pre- sent time in the fully collectivized districts, based upon the simple pooling of the peasants’ | means of production. Let us take for instance the collective un- dertakings of the Choprin districts of the for- mer Don province. Outwardly these collective farms scarcely differ technically from the small peasant farm (few machines, few tractors). | And yet the simple combination of the peasant means of production in the form of collective farms has produced an effect undreamt of by our practical workers. How has this effect been expressed? In the fact that the transition to collective farming has brought with it an increase of the cultivated area by 80, 40, and } 50 per cent. And how is this “dizzy” effect to be explained? By the fact that the peasants, powerless under the conditions imposed by, in- dividual labor, found themselves converted into a mighty force when they combined their tools and joined together in collective undertakings. By the fact that it became possible for the peasantry to till uncultivated land and cleared woodland, difficult of cultivation by individual labor. By the fact that it was made possible for the peasantry to get the cleared woodland into their hands. By the fact that the tracts of land hitherto uncultivated, the occasional untilled spots, and the field borders, could now be cultivated. | _ The question of the cultivation of untilled | land and cleared woodland is of the utmost im- portance for our agriculture. We know that | in old Russia the pivot upon which the revolu- tionary movement turned was the agrarian question. We know that one of the aims of the agrarian movement was to do away with the lack of land. At that time there were many who believed that this shortage of land absolute, that there was no more free cult able land to be had. | And what actually transpired? Now every one sees plainly that there werd dozens of mil- lions of hectares of free soil in the Soviet | Unio: The peasant, however, possessed no possibility of tilling this soil with his inade- quate tools. Since he was excluded from the possibility of cultivating difficult and woodland ground he inclined to the “soft soil,” the soil belonging to the landowners, the soil adapted to tillage with the aid of the implements at the disposal of the peasant under the conditions of individual labor. This was the cause of the “shortage of land.” It is therefore not to be wondered at that our grain trust now finds it possible to place under cultivation twenty mil- lion hectares of virgin soil, hitherto untilled by the peasantry, and indeed uncultivable by individual labor with the equipment of the | small peasant farmer. The importance of the | collectivization movement’ in every one of its phases, whether its most primitive phase, or in the advanced phase in which it is equipped with tractors, lies in the fact that the peas- | antry is now placed in a position to till uncul- tivated and woodland soil. This is one of the advantages of collective farming over the in- dividual peasant farm. It need not be em- more incontestable if the primitive collective farms over the individual farms will be even- | more incontestable of the primitive collective | farms themselves are given the possibility of concentrating tractors and combine machines in their own hands, (To Be Continued) Notice of Decision of the Cen: tral Control Commission of the Communist Party on the Case of Vanni Montana Having disconnected Vanni Montana from | the Communist Party (in the spring of 1929), | because of reports of unreliability, the Central Control Committee of the Party has recently passed a final decision, by which Montana is | declared outside of the Party and disqualified | for admission into the Party as an unreliable, 1 petty-bourgeois individual. , Besides information as to his previous ac- tivities and conduct, the Central Control Com- | mission acted also upon the basis of Montana’s un-Communist actions during the period of disconnection. | | That Montana played. a double role toward the Party has now been plainly demonstrated by the fact that, after learning of the Central Control Commission decision, Montana arranged a meeting in the Rand School together with other anti-Party elements, CENTRAL CONTROL COMMITTEE COMMUNIST PARTY OF U. S.jAs J \ _ y 4