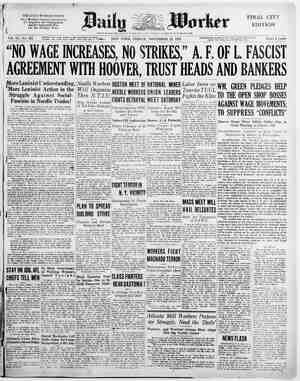

The Daily Worker Newspaper, November 22, 1929, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

‘ublishing Co., Inc elephone Stuyvesa » the Daily Worker. 26- Page Four Gans, except. Sunday, at 28-28 Union nt 1696-7-8. Cable: “DATWORK.” 28 Union Square, New York, N. ¥. By Mail (in New York only): Central Organ of the Communist Party of the U. 8. A. SUBSCRIPTION RATES: $8.00 a year: By Mail (outside of New York): $6.00 a year; $2.50 three months $4.50 six months: $2.00 three months $3.50 six months; | PARTY RECRUITING DRI\ Strengthening Our Party Organizationally -- Forward with Recruiting Drive! SMITH. ening our Party organizationally and nd in hand—was to get rid of the ) leadership of Lovestone and his renegade clique. y very effectively+in achieving this task. rotten anti-C The C. 1 Under the attacks ¢ down to its | derstand h the capitalist class, from Morgan and Hoover nd Cannon, the Party must un- n organization stronger than all the combined te: from the army and police down to the nization that cannot be destroyed and will be able to lead the working class and sharper mass struggles forward to the vic- keys, Lovestone forces of movies which, of America in broader of revolution. n spite ¢ make our whole membership under- the Party, its tasks and how they al level of our membership must be onsciousness must be steeled through a kers School, or in District Party 10st lively activity of self study in our organizational work of every member, rough permane through the t milite through syster Strengthening our Party means its Bolshevization. Organizationally the m importan ure is to bring the Party nearer to the masses especially nearer to the masses of American workers. This means to root the Party shops, mines, etc., i.e., to make the basis al politically active shop nuclei—no bluff-nuclei of the Party a f casually built up with no organizational strength and less political in- fluence. Without shop lei in the largest and most important fac- tories in the steel, coal, oil, chemical, and other key industries of this country, our Party will not be able successfully to meet and throw back the attacks of the bourgeoisie; still less will it be able to lead a vic- torious attack on the whole capitalist society. Only with well function- ing shop nuclei, especially in the all-important war industries, can, we fight for our legality and if forced down to illegality, continue our The most important feature of our membership drive is to make our Party an organization of shop nuclei instead of a conglomeration of “international branches,” street nuclei and in some instances, routine units—or rotten units—with meager political activity and no power of resistance in case an attack from the capitalist state. One of our bad routine mistakes is that we attempt to lead only through sending out of circular letters with the most splendid decisions —seldom carried out. Decisions must be carried out, and comrades or leading committees responsible for failure to carry them out must be taken to task by the Party. The beginning will be made with the membership drive; no member, no Party committee, no Party paper, will escape responsibility in case of non-carrying out of their tasks. To this end a system of reporting must be established. Every member in every nucleus must report to his or her nucleys at the end | of the membership drive what she or he has done, and if he or she could not do the task assigned, give the reasons why. Every nucleus must hand in a complete report about its activity for the membership drive to the section; every section to its district; and every district to the Central Committee. No unnecessary delay will be tolerated in delivering these reports. Every nucleus ought to have a meeting at once after February 10, 1 with all members present, where the results of the campaign are summarized. Not later than February 20 every district should have its final reports on the way to the C. C. But the system of regular reporting must be established not only for the time of the membership driv After the drive the Party will mercilessly insist upon a atie reporting from everyone, from every unit, every organization that has received certain tasks to fulfill. Only in this way will we be able to control the carrying out of decisions. Our Party press has a very important task in our organizational work. A Communist paper has altogether different tasks than a bour- geois newspaper. A Communist paper must first of all be an agitator, educator and organizer of the Par Most of our papers forget this, the Daily Worker not excepted. The Party cannot for instance tolerate that the outline for our membership drive, week after week, remains unpublished in most of our Party papers; that the Daily Worker im- mediately before this most important membership drive, failed for many days to publish a series of articles written and long ago sent in, to the Party in preparing for this drive. And the Party will, during the drive, not for a moment tolerate that a single paper should fail to carry on this drive as a real campaign; that is, to have every depart- ment of the paper reflect the drive in most of the headlines, in most of the news items, in artic (not only in special articles written for the drive, but in all arti of the paper), ete. When the Party carries on a campaign, this campaign must penetrate the whole Party press. Only in such a way can we make it a success. Not only the pregs, but our whole Party activity must be penetrated by this campaign of building shop nuclei and uiting new members for our Party. It must be a real campaign with the most complete mobilization of all Party resources. Leadership through circular letters means that even the best decisions in most cases remain on paper. Per- sonal contact, direct leadership through instructors in all fields of activity must be established. The C. C. must give personal leadership to the districts, the districts to the sections, and the sections to the nuclei. More personal contact, less bureaucratic, written orders. More instructions about how a thing is to be done, not only orders from above what to do. Strict discipline—much more of it than our Party ever has had—yes, and broader Party democracy. Our leadership must be based on authority, on knowledge how to lead—not on functionary titles! More proletarian self-critic in our Party, a complete break with all sleepy traditions of old social democratic lifeless routine! More political life in our units—revolutionize our nuclei, teach them to take up questions nearest at hand and to combine them with our general problems of national and international character; that is combine the local struggles with our general struggles! ai Our Party fractions in non-Party mass organizations do not fune- tion yet. Even where we have such fractions organized, their work is too poor, too maneuvering, too spontaneous, too casual instead of sys- tematic, militant and aggressive. This holds true regarding our frac- tions in the trade unions (we have too few and too weak fractions both in the old and in the new unions) and especially in the language mass organizations. The recruiting drive means an intensification manifold of all our fraction activity in all mass organizations. Every neglect of this work will be deemed a very serious shortcoming by the Party, and every member or organ responsible for such neglect will have to give real reasons or face the responsibility. No paper-fractions will be tolerated by the Party; activity and results achieved from this frac- tional activity are the only factors that count. Our auxiliary organizations such as, I.L.D. and W.LR. are today not auxiliaries of the Party; the Party is an auxiliary to them. They have not yet understood how to reack masses outside of the old circle of Party influence. Both the LL.D, and W.I.R. must understand—and “the Party has to lead them in this work—how to approach new strata of the working class, and especially American strata of workers, or -they will not be able to fill the tasks attributed to them. No splendid isolation in old spheres—march forward on new roads to contact with new and larger masses of proletarians. These are only a few of the most urgent tasks in our work of strengthening the Party organizationally. The outline for the mem- bership drive mentions more of them. Not every unit of the Party can carry out all these tasks, our leading committees must understand how to concentrate, must show our nuclei what are the most urgent, the most important tasks and concentrate our forces on fulfillment of them. Our fractions in trade unions (old and new) must get advice from their leading bodies. The same applies to our language fractions. Concentra- tion on the most important issue, away from chaotic, primitive methods —systematical leadership of our activity via simple and basic tasks, to more involved and complicated issues. ‘ Make our Party a Communist Party of shop nuclei. At least a few active, fighting, Communists in every one of the most important and largest factories and shops in America! If that is achieved we have ° the basis for a strong organization and we will be able to tackle ou other tasks@vith greater success than hitherto, % ¢ 4 = |(pportunism in the Cooperatives To the Members of the Cooperative Central Exchange: To the Members of the Tyomies Publishing Association: To All Members of the Communist Party U.S.A., District 9: Dear Comrades: Petty bourgeois and anti-proletarian influences are making them- selves felt more and more definitely in the workers’ cooperaitve move- ment. Some of the leaders of this movement, although pretending to be revolutionists, make themselves the spokesmen and carriers of these in- fluences. This is especially evident in Superior in the Cooperative Cen- | tral Exchange where George Halonen and Eskell Ronn are flaunting the interests of the thousands of proletarian cooperators. | Workers’ consumers’ cooperatives can be successful only if they be- come effective aids to the workers in their struggle against capitalist | exploitation. Whether the workers’ consumers’ cooperative can sell the pound of coffee cheaper or whether it cannot does not merely depend upon the specific shopkeepers’ qualification of the clerks or managers of the cooperatives; it depends on the confidence which the cooperative | as an institution can inspire among the masses of toil and exploited as an aid in their daily struggles against the capitalists and against cpitalism. It is the denial of this fundamental fact that makes the Warbasses and Alannes such dangerous enemies to the workers’ cooperative move- ment. Warbasse’s and Alanne’s enmity to workers cooperatives is dressed | in the innocent looking formula, “no politics in the cooperatives!” But “no politics” merely means “keep out all politics that collide with bour- geois polit ” It means a prohibition against any challenge to bour- geois political ideology and leadership in the cooperatives. Anyone who raises this ery of “no politics”-in a workers coopera- tive is an agent of the bourgeoisie, no matter with what cloak he may attempt to cover himself. George Halonen and Eskell Ronn who are now raising’ this banner of Warbassism in the workers’ cooperative movement are thereby at- tacking the very life of this movement. The masses of workers and toiling farmers in the workers’ consumers’ cooperatives must rally to defeat them. George Halonen and Eskell Ronn both have been members of the Communist Party and have held leading positions. They are now try- ing to utilise the confidence which the workers placed in them as Com- munists against the workers and their interests. Théy are an element foreign to the aims and aspirations of the exploited masses. Their at- titude is not new. George Halonen was associated in the Finnish language section with all social democratic elements that had made their. appearance at one time or another in the Communist Party. He was with Lore, with Askeli, with Sulkanen. When our American Communist Party was formed, it met the determined resistance of all social demo- cratic elements. These elements were very strong within the then Fin- nish Federation. Almost the whole leadership was anti-revolutionary. | This social democratic element tried to cover up its political difference, It tried to hang on to the mass organizations with their club houses, | newspapers, publishing companies, printing plants, consumers’ coopera-* tives, etc. It hoped for better times. The cleansing of the Finnish Section of the Communist Party, like all of its other sections, was the problem of its bolshevization. Every step forward made in the process of bolshevization was combatted openly or secretly by some or all of the remaining reformists in the ranks of the Finnish Section, But the process of bolshevization pro- ceeded, in spite of these elements. Our Finnish Section rid itself of such outstanding social reformist elements as Alanni, Laitinen, Askeli, Bowman, Sulkanen and others. These traitors to the working class interests found that desertion of the cause of the proletariat is not tolerated by the revolutionary Finnish workers in the United States. Those social democratic elements which remained in the Party carried on their fight on the ground of apparently non-political issues. But all these issues aimed at the undermining of the influence of the Party and “its leadership. Comrades who were loyal Party members and fought for the policies of the Party were sure to be attacked on ostensibly per- sonal grounds. Persistent defense of the Party line was denounced as factionalism. y This course of the enemies of the working class within the Party was facilitated by the factional struggle in the Party. The prevailing factionalism led to measures on the part of the leadership of the Party which were dictated by factional expediency rather than by political consideration. These conditions made it possible for the political dif- ferences to hide themselves. Only now and then did these differences appear openly. But when they appeared, they showed the full depth of the danger. One incident that illuminated like a flash of lightning the anti- proletarian tendencies in the Finnish Federation was the action of Eskel Ronn in the summer of 1928. During the stay of the strike-breaker Calvin Coolidge, then president of the United States, in the “summer White House” near Superior, the Chambereof Commerce of Superior organized a public reception for Coolidge. Eskel Ronn, a member of the Party and, incidentally, manager of the Cooperative Central Ex- change, was invited by the Chamber of Commerce to serve on the re- ception committee. He accepted. For this he was expelled from the Party. The social democratic elements still within the Party in Su- perior were ready to forgive Ronn and were busy to belittle his “error.” Their lack of revolutionary feeling could not understand what any revo- lutionary metal miner or lumberjack will understand without explana- tion. Any revolutionary worker would reject with scorn a proposal to “honor” strikebreaker Coolidge or any other tool of capitalism by serv- ing on a reception committee. A revolutionary worker cannot make the “mistake” of accepting service on a reception committee for Cool- idge. Ronns acceptance was not a mistake. It was the first and un- guarded reaction of one who sees nothing wrong in principle in such an ; act but who might, on more serious consideration, come to the conclu- | sion that it was otherwise an unwise act. | Ronn’s action and consequent expulsion did not make him an out- | cast among the leading spirits of. the Finnish Section of our Party in Superior. On the contrary, he became a martyr. He was pictured a victim of “persecution” by the Central Committee representatives of the Central Committee who participated in Communist Fraction meet- ings in Superior were usuaelly considered fdreign usurpers by these “Communists” while they found it perfeetly in order to invite Eskel Ronn, the expelled Party member and ex-reception-committee member to Coolidge, to the same meeting. The ideological leader for this tolerance toward Ronn and intoler- ance toward the Party was George Halonen, a close co-worker and | protagonist in their time of Askeli, Bowman and Sulkanen. He man- aged, however, to remai in the Party. Although he never publicly dissociated himself from these traitors, he was careful enough not openly to associate himself with them after their unmasking. There was ample evidence, however, that he associated freely with them. Ar- ticles published by the social democratic Raivaaju and speeches by Sul- kanen are clear indications that George Halonen kept up connections with the anti-Party elements, supplying them with information and se- cretly supporting them. George Halonen is educational director of the Cooperative Central Exchange. This organization is built and maintained by revolutionary Finnish workers. These workers want the cooperative to be an instru- ment and.a school of cJass struggle. They want it to be an aid to the workers in their class battles. George Halonen utilised his position as educational direetor to counteract this will of the rank and file of the Cooperative. Instead of training the functionaries as revolutionists, he trains them as grocery clerks. A glaring illustration of Halonen’s conception of revolutionary “education” is .his several-hours’ speech at a workers’ club picnic at Inshpeming before five to seven thousand workers where he used a few minutes to speak perfunctorily about the revolutionary movement and the rest of the time recited the price list of the groceries of the Cooperative Central Exchange. When the Party takes up criticism of actions such as Ronn’s or Halonen’s, it is continually confronted with the argument made by those peopie that the Party criticism makes it hard for them to work among the masses. Therefore, they conclude, this criticism should not be made. Their petty bourgeois socia] democratic conception prevents them from seeing that it is the duty of the Party to win the confidence of the workers away from them as long as they utilise their influence among the workers in order to mislead them. Halonen’s social democratic point of view found clear expression after the receipt of the Address of the Communist International to our Party. This Address was a rallying signal for the struggle against the , Right danger. But in Halonen’s mind it became an action on the part of i the Comintern ending the:“crazy leftism of the Central Committee.” His anti-proletarian conception sees in every proletarian action disturb- ing factors and classifies them as “crazy leftism” while he attempts to raise opportunist inactivity upon the pedestal of realism. . This is Loreism. It leads to a paralysis of the revolutionary Party. The re- sults of such a policy are open resistance to revolutionary action. Halonen was a Loreite and, evidently, still is. One of the disciples of Halonen in Hancock, Mich., voiced his revolutionary conception by con- demning the anti-war demonstrations of August First on the ground that they “made trouble.” The same objection is voiced by Halonen’s fol- lowers to the organization of the metal miners in Upper Michigan and Northern Minnesota. The motto of these Loreites is: “It can’t be done. Why try? It only brings you trouble.” Another manifestation of the serious Right danger in the Finnish Section in Superior is apparent in the propaganda concerning the Com- munist policies of “Tyomies.” Tyomies is a revolutionary paper. It was established and is maintained by revolutionary workers who want it to be their instrument. of strugglé. These workers have accepted the leadership. of the Communist International. ‘The Communist Inter- national insists that Communist papers are guided by the Communist International exclusively. The revolutionary value of the Comintern and the Communist. Party lies exactly in its revolutionary principle, program and tactics and in the revolutionary steadfastness with which this program is carried thru. The only guarantee for the revolutionary quality paper is that it sticks to the program of the Party and that it makes itself the organizer and mouthpiece of the revolutionary workers in all campaigns and. struggles. The Communist International con- sidered this so important that it made one of the 21 conditions of admis- sion to the Communist International that “All periodical and other pub- lications as well as all Party publications and editions are subject to the control of the Central Committee of the Party independently of whether the Party is legal or illegal. It should in no way be permitted that the editors are given an opportunity to abuse their autonomy and carry on a policy not fully corresponding to the policy of the Party!” Party control of its papers and of the activities of its editors has always been the center of the most bitter attack of the social democratic remnants within the Party. These anti-revolutionary elements have al- ways considered it their inalienable right to utilise their chance con- nections with the revolutionary press for dissemination of their non or anti-Party viewpoints. Against control by the Party they raise, first, the issue of the right of opinion and, second, the issue of control of a paper by its readers. The first of these-arguments is petty bourgeois anarchism. The revolutionary section of the working class has the duty to guard its institutions and papers against their being misused for anti-proletarian purposes. The revolutionary working class allows freedom of opinion only within the boundaries of pro-working class principles. Where these principles end, the duty of struggle against the so-called freedom of opinion begins. Revolutionary working class papers give voice only to fighters FOR the working class. A revolutionary working class paper is not.a platform of debate but is a weapon in the class struggle. The efficiency of the weapon cannot be permitted to be impaired by anti- “revolutionary contents. The second of these issues, control of the paper by its readers is a demagogic cloak of bureaucratism. Those who raise the issue of con- trol by the readers raise it because they want to escape control. They raise it because they hope that by this method they can cover their own bureaucratic misuse of the paper and can win the unsuspecting reader for support against control by the working class through their only working class Party. The Tyomies has recently become again and again the instrument of anti-Party elements. Attacks against the Party were made under the disguise of attacks against individuals, Those responsible for these attacks knew that the individuals they attacked were voicing the de- sires of the Party and were carrying out the policies of the Party. These activities are impairing the effectiveness of Tyomies as a weapon in the hands of the revolutionary workers. They are aiming to under- mine the influence of the Communist International which is the only guard and guide of the revolutionary interests of the proletariat. Under the leadership of Halonen and Ronn, some bureaucratic. ma- chinery was perfected in the Cooperative. The class interests of the mags organized in the Cooperative are openly flaunted and disregarded by these bureaucrats. The desires of the masses of the membership, to have in the Cooperative an aid in their struggles against the bosses are frustrated by Halonen and Ronn who are attempting to manage the cooperatives merely as grocery stores. In order to escape control, they shout about the right of control by the membership, By shouting about this control which they know cannot exist, in a political sense, they want to escape the control which the Comintern puts upon them as members of the Party in the 21 points. The Comintern demands that “Wherever follower’ .of the CI have access and whatever means of propaganda are at their disposal, whether the columns of news- papers, popular meetings, labor unions or cooperatives, it is indispensa- ble for them not only to denounce the bourgeoisie but also its assistants and agents—reformists of every color and shade.” Halonen wants to make the workers believe he is a Communist. The revolutionary work- ers know that a Communist is a revolutionist because he accepts and follows the lead of the Communist Imternational. There are no other revolutionists. The revolutionary workers expect the Communist Party to guard their interests in all organizations, including the cooperatives. They expect the Communist Party to exercise the contro] over its mem- bership also in the Cooperatives, a control which the masses of the rank and flie cannot exercise by the very nature of the organization. The “freedom” of control by the-membership as talked about by Halonen and Ronn turns in reality to a “freedom from control” for the bureau- crats. ° The slogan of Halonen and Ronn for rank and file “control covers up a struggle of unprincipled bureaucrats against rank and file control. That is why the campaign of Halonen finds such a ready and sympa- thetic echo in the organs of the enemies of the working class, in the social democratic “Raivaaju” and in the petty bourgeois anarchist “In- dustrialisti.” ey The Communist ‘Party sees before it the tremendous tasks of the -pre-war period. It endeavors to concentrate all efforts upon the or- ganization of the unorganized masses. This is especially important for the slaves of the copper And steel trust in upper Michigan and North- ern Minnesota. The poor farmers in this territory, many of whom former slaves of the steel and copper trusts, must be won and organ- ized for the support of this campaign. Halonen takes issue with the Party on this policy. He does not accept the Communist International and our Party’s analysis of the third period. He prefers the issue of selling groceries to the issue of organizing a revolution. Instead of subordinating organizations such as cooperatives to the interests and necessities of the basic struggle of the working class he insists on subordinating this basic struggle. to the price list of the cooperatives. With his social democratic, petty bourgeois shopkeeper’s mind he does. not. recognize that the success of the workers’ cooperative (and even the attractiveness of its price list) are dependent upon the degree to which the cooperatives succeed in strengthening. the workers in the class struggle. Halonen’s shopkeeper conception is that if the coopera- tive can sell cheaper, it is successful. Any revolutionary worker can inform Halonen that if the cooperative succeeds in being an effective aid to the workers and toiling farmers in the class struggle, it will inspire confidence (and subsequent participation). on the part of the masses of workers in them and will thereby enable them to lighten the economic burden of its members, yes, and to sell cheaper. In other. words, an attractive price list of a workers’ cooperative is not the em- bodiment but the result of its success. The success of Tyomies as a mass paper of the Finnish speaking proletariat, the success of the cooperative movement as an instrument of class struggle in the hands of the masses of the Finnish proletariat demand uncompromising fight of the policies and tactics of Halonen and Ronn. The policies and tactics of Halonen and Romn are the policies and tactics of social democracy. The program of Halonen does not aim at a defense of the Tyomies for the workers. It defends the Raivaaju against the revolutionary Workers. It wants to deliver Tyomies to the bunch of social democrats who daily betray the interests of the working class in Raivaaju. The policies of Halonen do not aim to defend the cooperatives for the revolutionary workers. They want to deliver the cooperatives to Warbasse who daily betrays the interests of the work- ing class in the Cooperative League of North America. . « Against these social democratic maneuvers of Halonen, the Com- munist Party calls upon the Finnish, workers everywhere and upon those in Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin in particular, to rally round the Party of the Communist International in the United States. “It calls upon them to help in strengthening the Tyomies as a weapon in. their struggles, by insisting upon’ a clean-cut revolutionary ,editorial policy. The Communist Party calls upon workers to help it to combat bureaucratism in the cooperatives so that the cooperatives may become a most effective aid in the class struggle. It calls upon them to repu- diate the social democratic line of Halonen and help the master od 4 OF BREAD Reprinted, by permission, from “The City of Bread” by Alexander | Neweroff, published and copyrighted by Doubleday—Doran, New York. TRANSLATED FROM THE RUSSIAN (Continued.) Mishka stepped back and pulled his hat off. The rain poured down, the wind blew, and. Mishka stood there like a beggar, near the footboard of the engine, holding his old torn cap in his hand. The engineer came along with his flaming torch, and the livid flare, hissing in the rain, fell on Mishka’s face and drew it out from the darkness. “Have pity on me, uncle, in the name of Christ!” Mishka cried. The engineer said nothing. Mishka stood there. . The rain poured down, the wind blew, they kept on hammering at the wheels, and Mishka stood there with uncovered head, shrinking against the foothoard of the engine, tremblitg with cold and despair. Again the engineer appeared with his flaring torch, and this time Mishka seized him by. the hand. “Uncle, I'll die if you leave me here.” The engineer stopped. Mishka did ‘not know who he was himself any longer; a famine boy, from the Buzuluk district. He had set out for Tashkent to get bread. His comrades had deserted him. No one would let him on.the train. Couldn’t they manage to take him along? He could pay a little, if necessary—he had a knife and a thousand rubles. “Wait here!” said the engnieer. “The conductor will be along in a moment, ask him.” Mishka fell on his knees, stretched out his arms, cried out des- perately, in the tormented voice of his pain and despair: “Uncle, comrade, in Christ’s name take me along! Tl diet” The engineer said nothing. For a long time he kept.on moving around the wheels and hammer- ing, and then he went off to the station. The rain poured down, the wind blew, and Mishka stood there by the engine wheel, in a torment of suspense and fear. Suddenly, without asking anyone, he climbed up into the engine. He warmed his back a little by the engine chimney, and then he warmed his chest. Then when his chest was a little warmer, he turned his back again. Toward morning the rain ceased. Everything was silent and misty and dead. In the pale light of dawn the station became visible and the Kirghiz tents behind the station. ‘ The engineer came along. He saw Mishka’s blue face, and Mishka’s tormented eyes, filled with pain. In a voice that was notgangry, he, inquired: “So you’re coming along with us, comrade?” Mishka answered piteously: “Don’t chase me: out, little uncle. all night long... .” “Where are you bound, for boy? gol” I'll die here, T’'ve been freezing with cold You'll go under wherever you Things are easier when people talk together. Your courage comes back again. Mishka told where he came from and where he was going. Then he began to brag a little. If he could only get to Tashkent, he had relatives there. Twice they, had written to Mishka’s mother, and begger her to send him. They wrote: if he likes it with us, he can stay here for good: but if he doesn’t like it, we will send him back, with a ticket. ° The engineer listened, and smiled, glanced at Mishka’s blue lips, and suddenly said: “Come along with me.” At first Mishka did not believe it. When he found himself by the engine fire, and all about him saw familiar levers, wheels, knots, bolts, keys, handles, and the fiery throat of the engine, with its leaping flames, fantastic thought began to circle through his starving head: what sort of place had he fallen into? The engineer pulled one of the levers—up above, over the roof. a. whistle sounded. He pulled another lever-—the engine stirred, got under way: first slowly, cautiously; then it broke loose, and dashed along at such a speed that Mishka’s heart stood still and his thoughts began to turn somersaults in his head. What force was this that bore them along, and of whose contriving? On the upgrades, the engine toiled along slowly, then it would dash off again at full speed. The engineer in his black shirt leaned out of the window and smoked his pipe. Another man kept throwing wood down the engine’s fiery throat, and suddenly he picked up Mishka jokingly and called over to. the engineer: “Comrade Kondratyev, shall we throw him in instead of wood?” “In with him,” laughed Kondratyev. That will make it hotter!” Mishka observed these new people closely: he saw that they were joking with him, and this joking of theirs and the warmth of the en- gine, made his heart feel lighter. And when Comrade Kondratyev turned a little stopcock and filled his ketle with boiling water, drank himself, and gave Mishka a tin cup of hot water, Mishka, happy and warmed by this friendliness, said: “Tt’s a long time s‘nce I had hot water to drink!” And then Kondratyev broke off a piece of bread. “Have some?” No, it wasn’t the bread that did it. It didn’t begin to satisfy his hunger. The bit of hard bread was much too little. No, it wasn’t the bread that made him happy, but the friendliness and the kindly smile op Comrade Kondratyev’s face. He sat on the warm stove, completely “at home, kept falling into a doze, sleepily fondled his knife in his pocket, thought peacefully and happily: “What good people!” As they approached a large station, Kondratyev said: “Now you'll have to get off, Michaila: the engine is going into the station’ yard for repairs. We must fix it up so it won't play any tricks on us, then we'll go ahead to Tashkent. . .. It’s not much further now.” * Mishka hung his head. > “What are you afraid of?” ¥ “People are different! Some let'you on, some chase you away.” Kondratyev patted him on the shoulder. “Don’t afraid, Michaila. You're coming with me, only don’t run too far from the station. When the engine leaves the yard, I’ll whistle twice, and then hrrry back here. Understand? If you won't see me, wait for me... .” “Thanks, little uncle, I'll do as you say.” “All right.” % “And meantime I'll take a look around the station, Maybe I'll bump into some of our own mujiks. ' Do you smoke cigatettes?” “Why?” ‘f 3 4° “Maybe I could buy you a couple at the market.” .Kondratyev laughed. “If you buy me cigarettes I won't take you along......” When they arrived at the station, Mishka gave Kondratyev a last friendly glance and jumped off the engine. Then he sat. down by the train, took off his bark sandals, unwound the linen strips, threy away the torn sandals, and tying the stockings together with the strips, flung them over his shoulder and Went off to the market place barefoot, his cap on the back of his head. (To be continued) * Party to mobilize the workers for the struggle against impérialist war, It calls upon them to rally for a most intense organization campaign among the unorganized slaves of the steel and copper trusts. It calls upon them to repudiate the principles of the Second International enun- ciated by Halonen and to maintain the principles of the Communist In- ternational, the principles of Bolshevism which guided the victorious | revolution of the Russian proletariat. Down with reformism, opportunism, Loreism! Long live the workers cooperatives as weapons in the cl struggle! Long live the Communist International! Long live the Communist Party of the United States! CENTRAL COMMITTEE, COMMUNIST PARTY OF U.S. Ae SECTION OF THE COMMUNIST,INTERNATIONAL, .