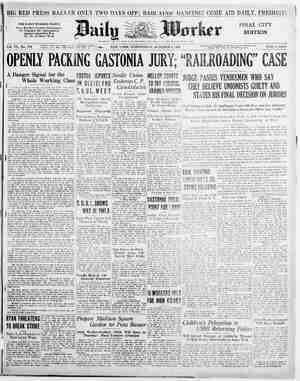

The Daily Worker Newspaper, October 2, 1929, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Published by the C: odaily Publishing Square, New N. ¥. Telephone Address and mail all checks to t Stay Page Four he Daily Worker, 26- 28 Union Square, New York, N. ¥e gan of _dorker t Party of the U. 8. A. SUBSCRIPTION RATES: By Maj! (in New York only): $8.00 a year; By Mail (outside of New York): $6.00 a year; $2.50 three months $4.50 six months; $2.00 three months $3.50 six months; “& LIFE PARTY L OUT WITH THE DISRUPTERS Unit 14f, section 3, meeting Sept. 9: “After a most thoro di and the urgent need for the elimin: in the CPUSA, our unit decide present working within the Party renegades and backs wholeheartedly the line laid down by the 10. plenum and followed by the CC of the CPUSA. distr. passed the following motion at i ion on the 10. n of remnants of fa jonalis for a stern fght against all those at in the interests of the Lovestone Our unit also condemns and repudiates the rabid antiparty speech @ J. O. Bentall made at our unit meeting.” Voting for this resolution 16 members, against Bentall and his wife. The Worcester Section committee adopted a resolution demanding the removal of Bail already in August and spoke about the raiders of the NO: “We assure these tools of the bourgeoisie that we will stand erect with the CC and fight stubbornly of the CI against all our enemies. We ask the members of the for the American section Party who take a conciliatory attitude towards the renegades so that they can be placed where they belong: in the camp of the bourgeoisie.” Liars in All Their Glory By KARL REEVE. The series of articles now being run in the New York Evening World are proof of what the National ile Workers’ Union has known since the beginning of it npaign against the speed-up in the South, that the struggle of the southern textile workers is not against one mill—the Manville-Jenckes—or against the employ tion of the country. In the campaign of the National Textile Workers’ Union for the eight hour day, against the speed-up, and for higher wages, the union is faced with the opposition of the entire strength of U; S. finance capital, the entire strength of the government, city, state and national. In its determination to drive the National Textile Workers’ Union, the International Labor Defense and the Communist Party out of the South, in other words their determination to prevent the organization of the mill workers into the union, the Manville-Jenckes company and the-southern mill owners have merely to beckon when they need help, to enlist the support of the New York capitalist daily, which goes through its contortions of lies and slander in a manner from which even the Gastonia Gazette and the Charlotte Observer may well take lessons. The front page article of the World on Sept. 19 is as filthy, as fascist, as much a call to murder of workers, as much a tissue of cheap lies, as anything the Gassie Gazette ever produced, There is “no. terror in Gaston County,” we are told. Just a few of the boys good naturedly “spanking” a few “wild reds” who are a nuisance any- how. Whereas the mill owners’ mob which nearly killed Ben Wells, did it avowedly because he was a union organizer and under the slogan, “Down with the union,” the World deliberately lies and says the mob was against “the reds.” The very hirelings of Manville-Jenckes, Bulwinkle, a very bad lawyer but an expert mob leader; Dr. Johnson, who evicted children from their homes when they had small pox and said, “They’re not sick”; the mill superintendents who were identified more than once as leaders of the mobs against union organizers, are paraded in the World as virtuous people who “decry violence.” The world, publicity agent for the mill owners, finds everything getting along lovely in the Manville- Jenckes mill. Only the old women workers, we are told are “sour.” Of course no mention is made of the twleve-hour day, which, combined with the speed-up and low wages, caused the strike. The speed-up turns, in the World, into the “remarkable dexterity” of the workers. The “dope book,” the company store which keeps the workers per- petually in debt to the mill, turns into a benefactor of the workers in the World’s columns. . The cold blooded murder of the unarmed Ella May Wiggins by the Manville-Jenckes mob, is slurred over, just a little accident of the mischievous but well meaning “community.” The homes of the work- ers are a little dirty, some of them, but that is the fault of the workers. There is a little overcrowding, and “an unhealthy condition arises from the fact that night and day workers move in and out of beds on too short headway.” But, says the World, the cottages are “neat.” The lies spread about the Gastonia strikers’ delegation to Wash- ington, of which the writer was in charge, are repeated and added to by the World. A mysterious “interview” with one of these workers is “reported.” “We were told not to take a bath,” says this mysterious person interviewed. Of course, the name of the membe rof the Wash- ington delegation is not given. This is not necessary when lies are manufactured against the workers. The Baltimore Sun said the Wash- ington delegation was typical of thousands of starved mill workers and the only “order” given the delegation was to tell the truth as to their conditions. The World blandly turns the pellagra-ridden, notoriously underfed, starving and overworked Southern textile workers into happy, well- ‘fed, contented, well paid workers for the altruistic, profit spurning, Big Brother, the Manville-Jenckes company. All we have to do is to sshut our eyes to the child labor, the fact that most of the mill workers have been to school less than four years, and large numbers not at all. “Some of the mill workers have been through high school.” All ‘we have to do is to shut our eyes to the crushing out of children’s lives in accidents in the Manville-Jenckes, to ignore the figures of average wages of $10 in the Manville-Jenckes mill, to ignore figures of huge profits. All we have to do is to forget the tearing down of the union head- | quarters by the Manville-Jenckes mob, of the eviction from the homes by the Manville-Jenckes deputies, of the kidnapping, murder and bay- onetting, beating and wholesale arresting of strikers and union organ- izers by the Manville-Jenckes agents; of the fact that the 16 strikers | and, organizers who led the strike are in jail, charged with murder and that those who were known to have murdered Ella May and half killed Ben Wells are at liberty; to forget that Solicitor Carpenter, and other city and county officials and police were leaders of the mob; that the Manville-Jenckes company pays the city’s expenses for prosecuting union members, that the Manville-Jenckes, in the person of the no- torious Bulwinkle, defends every degenerate like Troy Jones, when he‘ gets “playful” and throws dynamite, murders defenseless women, or beats young girls. ; Let us “forget” that Ella May was murdered. Let us “forget” ““that armed gangs, with the cooperation of the government authorities, ‘re roaming the roads spreading terror, trying to prevent meetings, and lynch union men, It is healthier for a reporter for a Wall Street paper to “forget” these things. Ask the reporter for the Daily News Record, who, when ~ he went inside the Manville-Jenckes mill during the strike, was almost lynched because he had interviewed union organizers. Ask Leggette Blythe, of the Charlotte Observer, who was naive enough to think he ~ “gould talk to Fred Beal, and got knocked on the head with a blackjack “and learned his lesson. Ask R. 0. Williams what pressure was exerted » «on him by the mill owners to try to get him to doctor his stories for , the Raleigh News and Observer. the same question. Ask Catledge of the Baltimore Sun The present situation, the united efforts of the capitalist class, of the Wall Street banks controlling the textile industry, and their gov- ernment, brings the Gastonia Gazette and the New York World to the fore in all their glory. What the mill owners want now, and what they are getting in the World, is a direct inciting to work their will un- harmed, and praised, to the mill owners’ mob, on the union members, a direct invitation, to beat, slug and murder union organizers. . The mill owners are determined to save their profits. They are . determined to get rid of the National Textile Workers’ Union, And any dirty little job like praising murderers of unarmed women, or in- _ citing to lynch union members, or lying about conditions, or, glorify- ing lynch law, police brutality, and Manville-Jenckes murder—the World, the paper of Wall Street, is glad to do for the class of which it is a part. s of one sec- | | GASTONIA 1929: CLASS By Fred Ellis The Peasant Movement in the Philippines | The Philippines are a purely agrarian country. The predominat- ing form of economy on the Islands and the chief occupation of the population is agriculture, The agricultural population, including the agricultural workers, comprises no less than 85 per cent of the total population. (The population of the Philippines is 12 millions). Despite the fact that the density of the population in the Philippines is far less than in a number of neighboring countries such as Indo-China, Indonesia, Chnia, and in spite of the vast tracts of land which are not cultivated and have no titles (as for nistance in the Southern Islands), where one-third of the area of the Philippine Archipelago is populated by less than a million semi-nomads), the position of the Filipino peasantry is very bad indeed. F According to the census of 1918, there were 1,855,276 individual peasant farms in the Philippines, more than 932,000 of which, that is, about half, owning not more than 0.35 Hectares of land each; about 500,000 farms had less than one hectare each, and 435,259 farms were on rented land only. There were over 90,000 land estates which were rented or used for plantations, large stats with ovr 100 hectares of land aech numbering more than 9,500, of which about 1,000 were in the hands of native landowners and the rest belonged to the for- eigners. Thus the entire cultivated land of the Philippines is so divided that 5 per cent of the owners have 70 per cent of the land, nad only | 30 per cent of the cultivated land falls to the share of 95 per cent of the peasant farms. The peasantry’s lack of land is constantly being aggrevated by the natural increase in the population and the further breaking up of the already small peasant lots. Thus, for instance, during the: period from 1903 to 1918 the average amount of land owned by the farms decreased from 1.6 hectares to 1.24 hectares, while since 1918, in view of the intensified development of plantation cultivatin of the peas- antry’s position is still further increased. The eviction of peasant- rentiers from the land rented by them and often cultivated by them from generation to generation, is becoming a mass phenomenon; ow- | ing to the arbitrariness of the local authorities not only rentiers are |. evicted but also peasant small-holders who are unable to prove their right to the land, and illiterate peasants as often as not being abso- lutely unable to do this. This all pursues the aim of creating the greatest possible reserves of cheap labor power for the big capitalist plantations which are continually growing. Besides this, the domination on the market, of monopolist organ- izations, which dictate their prices for the chief agricultural products such as sugar cane, hemp, tobacco, cocoanuts, and so on, the income of the peasant farms decreases to the very limit. It is natural, there- fore, that in view of all these conditions, the livingstandards of the Filipino peasantry are very low, The position of the peasant-rentiers, is still worse. The predom- inating system of renting is the share-system, when if the rentier | has his own cattle and equipment, he pays the owner half the harvest, while if he uses the owners cattle and equipment he has to pay two- thirds of the harvest. Of course, the peasant-rentier gets no discount in his rent in the case of the not unfrequent natural calamities, such as bad harvest, typhoons, floods, As the half or third of the harvest which is left to his share is not even sufficient to cover his most vital reduirement, the rentier usually contracts absolutely hopeless debts, which make him completely dependent on the land-ownr, who advancs the rentier seed for th new sowing or even rice for his food at fabulous interest. The usurious activities of the landowners—the scourge of | the Filipino peasantry—are very extensively developed. The Insolvent debtor (and debts go down from generation to generation), becomes | the absolute serf of the creditor, forced to work off his debt together with the whole o his family. This peonage system is even now very widespread in the Philippines, despite the fact that the laws reinfore- ing this system have been annulled, for the difficult position of the peasant is better measure for enslavement than any of the laws. In all the peasant uprisings, which are very numerous in the history of the Philippines, nad even now, the question of the struggle against the usurious pracitce, the struggle against peonage, plays a very im- portant part. At one time, under the threat of the detachment of the Sounthern Islands (The Southern Islands fo the Archipelago—Mindanao, Pala- wan and others—are the least developed, populated by semi-nomad Mohametan tribes, who are hostile to the Christians, who mostly populate the rest of the Philippines. This enmity is artificially kindled | by the Americans, who desire to separate the Islands in order to use 4 their lands for vast rubbed plantations), the Government of the Phil- ippines began to carry out a policy of colonising these islands, subsidis- ing the peasants who migrated to them. However, under the pressure on the one hand of part of the bourgeoisie, who feared that the sources of labor power would be exhausted, and, on the other hand, of the American Governor-General, the Parliament refused to endorse the necessary sums, andthis practically put an end ot the colonization, ° The agricultural workers comprise a very considerable section of the agricultural population of the Philippines. They number more than ‘ 2,000,000, practically half of them being women nad children, There is no need to state that the position of these workers is extremely bad. Their working day, which is not limited by legislation, usually lasts from sunrise to sunset; for isntance,.when gathering the sugar-cane at the plantation work is carried on in two shifts—day and night, despite the fact that according to official government data the work- ing day lasts 94% hours—while wages are so low that even when sev- eral mbme resof the family work, their earnings do not suffice for a more or less tolerable existence. The official living minimum in the provinces is 1 peso 82 centavos (1 peso is about 2 shillings), while the average wages for an adult worker, according to official data are 82 centavos, women getting 49 centavos, and adolescents 40 centavos. In reality the wages received are far lower, All available investigations into the history of the Philippines from the beginning of the Spanish rule (over 300 years ago) and during the 30 years of American reign afe full of peasant uprisings, as the inevitable consequence of the unbearable position of the peasantry. Last century alone numbered over 100 uprisings. At the beginning of the present century, exhausted by the arbit- rary measures dealt out by the Amercians to the participants in the first Philippine national revolution of 1896-1898, the peasant move- ment down. 1917, and from 1917 to 1925 there were 54 instances of so-called agrarian disorders, which involved over 50,000 participants. During this period the peasant movement acquired more organ- ized forms. In 1917 the first Peasant Union was organized, which conducted the rentiers strike, lasting for about tfwo years, leaving the field at the very height of the season. Of course, it needs no saying that all supposable repressions fell to the share of the strikers —they were evicted from the houses, arrested on th accusation of supposed spoiling or stealing the property of the landowners, and were thrown into prison for long terms. Despite the deprivations endured by them, however, the firmness of the union members, thir unanimity, increased the authority of the organization, and the num- ber of peasant unions began to grow rapidly, and in 1922 at the first peasant confress of the Philippines the “National Confederation of Peasants and Agricultural Workers of the Philippines” was fnuded, uniting the fromerly disunited peasant unions, having a membership of over 15,000. As formerly, the present influence of the conference, however, covered a far larger number of peasants and agricultural workers. The Conederation, led by a group of people revolutionary inclined, devoted to the cause of liberating the Filipino peasantry, is develop- ing its activities along the only correct line—close connections with the labor movement of the Philippnies. The Confederation affiliated to the largest workers’ organization of the Philippines—the Workers’ Congress, and through the Congress it is affiliated to the Pan-Pacific Trade Union Secretariat, and is thus drawn into the orbit of the labor and national revolutionary movement of the colonial and semi-colonial countries in the Pacific. Since the present year the Confederation has likewise been a member of the League Against Imperialism. * A new revival of the peasant movement is now taking place in the Philippines, , The intensified offensive of capital in agriculture and the growing investments, partially of native, but chiefly of American capital in the big plantations, are accompaniel by all sorts of evasions of the agricultural laws*of the country and the mass impoverishment of tens of thousands of peasants and rentiers estates as a result of the peas- ants being deprived of the plots of land cultivated by them, which by the labor of generations have been transformed from the swampy and wild lands of former days to flowering fields. The’ mass eviction of rentiers of which we have already spoken is taking on unprecedented dimensions, The consequences of this agrarian policy are already being felt in the growth of urban unemployment nad the offensive on the wages of both urban and agricultural workers. This policy naturally provokes the indignation of the peasantry which is expressed in the growing wave of the peasant movement. The peasants act in a united front with the* labor movement of the Philippines in this protest and resistance to the nitensified ex- ploitation of the toiling masses by the united forces of American im- perialism and native capital, The recent workers’ and peasants’ demonstrations in May in pro- test to the mass’ eviction of peasantry attracted ten of thousands of participants, The Confederation of Peasants and Agricultural Workers, which leads the peasant movement of the Philippines, at its last Congress drew up a militant program of action for the peasant organizations. This program, which has become the watchword of thegrowing peasant movement, contains the demands and call for the struggle for: (1) national independence of the Philippines; (2) for improving the position of the peasantry by nationalizing the big estates and mon- astery lands; (3) for improving the position of the rentiers by de- creasing the rent, prohibitnig evictions, discounts being provided for in case of natural calamities, prohibitnig compulsory labor and'peon- age; freedom of coalition, word, press, strike, and pickets, etc.; (4) with regard to the agricultural wérkers,—for the eight-hour day for adults, weekly rest day and two weeks’ vacation annually; for the recognition of the unions and collective agreements, social insurance of the workers at the expense of the employers or the state and old age pensions, and for the immediate extnsion of factory Igislation to the agricultural workers, fener: a 4 However, a new revival of the movement set in in 1916-° Position of Workers in China All eyes have been following up the heroic struggle of the Chinese workers during the last few years. Attention has been called to their bitter living and labor conditions, the harsh treatment they receive, their miserable wages, or the incredible length of the working day in China were it not-that these matters deserve the constant attention of everyone. Is it possible to forget, even for one’moment, that in some branches of industry in China, the working day lasts 20 hours? Can we pass over this? Is it not time to raise the alarm? fi In all branches of the small-scale industry and the handicraft trades, | where hundreds of thousands of workers are employed, the “normal” working day is somewhat shorter, although a 14 and 16-hour day is by no means rare. Thus, the Chinese worker spends nearly all his life in the factory, in unsanitary conditions, amid the din of the machines. Seventy per- | cent of the workers are not allowed any days off at all throughout the course of the year, the only exception being perhaps the Chinese New Year. Frequently, the workers eat their meals while tending the ma- chines, for in many of the enterprises, even in the largest, no meal intervals are allowed. Add to this the almost prison-like regime existing in the bulk of the enterprises, where the workers have to get special passes even to go to the lavatory, the abuse they suffer at the hands of the foremen, the frequent and unwarranted discharges, coupled with the absence of all safety measures—and we have a clear picture of what labor conditions are like in China today. The absence of elementary safety appliances is directly responsible for the numerous accidents that occur daily in the factories. The work- ers crippled in this way, unable to support themselves any longer, are thrown on the streets to starve. Mateial support in such cases depends wholly on the good will of the employer, but even so, these maimed workers can expect nothing more than a couple of dollars. Only when a fatality occurs does the bereaved family receive 20 or 30 dollars, and. then not always! Should we scan the wage-rates in force we see that things are just as deplorable. The following table shows the average monthly nominal wage obtaining in the various industries (in Chinese dollars): Men Women Unskilled Skilled Unskilled Skilled Cotton Mills ..... 9 26 15 BJ Railroad Shops . 15 ea ese rey Mining Trades .. 14 22 — _— Silk Spinning . 19 22 7.5 9 Other Industries 10 15 5.5 12 Children receive from 10 to 20 cents a day. There are branches of industry where wages are lower still. For example, in the canning industry the monthly wage of the women workers fluctuates between $2 .40 to $10.50, the men getting-from $2.40 to $15. In the sma shops we find juniors as well as children working only for their board, which consists of a miserable ration. Many different*fomrs of exploitation exist in China. In the central provinces, for example, the employers frequently pay, their workers part in money and part in kind, e.g., after working a whole month, the workers receive from one to three dollars in money, the balance of their earnings in maize, rice and beans. Tha tthe wages of the Chinese workers are truly miserable is made clear by the figures given above. But we only get a true idea of the actual position of things when we remember that a worker employed in a Shanghai cotton spinning mill has to spend two weeks’ wages to buy a pair of leather boots, a month’s pay to buy a pair of sheets, one day’s pay to buy two poundsof pork, ete. Much light on the actual position of things can also be gleaned from a study of the worker’s budget. Let us take a family of four (husband, wife and two children), where both the husband and wife are working receiving between 17-18 dollars. To live, such a family must make the following expenditures: 30 klgs. of ree—$8; veegtables and seasoning—$5.50; heating and lighting—$1.50; rent and taxes—$2; tobacco and drinks—$1; miscellaneous expenditures—$2; total, $22. This budget does not include a single cent for meat, or for fats, or for the nourishment of children. It is so meagre and poor in every respect that it would be impossible to take off a few cents to purchase a paper or a school-book for the children, to mention such items alone. But the workers never receive even these miserable wages in full. Fines are deducted. This always’ makes big hol in their wages. In China the workers are fined on the slightest pretext, which include late- coming if only for a few minutes, to talk to one’s neighbor during the work, failure to carry out foremen’s instructions, and so on. The foremen pocket a substantial part of the workers’ wages since they arrange for the employment of the workers. Usually they em- ploy their own countrymen when requested by the employers to get more workers. The employersand the workers having only to do with the foremen in al! financial matters. They pay off their workers and cheat them in the most unscrupulous way by paying the men “small money” having received themselves from the employers “big money,” which means that the men lose on an average of 30 percent of their ‘wages, The workers have to pay the foremen a definite sum of money, amountin gusually to a month’s or six week’s pay, for being employed. Afterwards the foremen have to be continually bribed if discharge is not to follow the good relations maintained. Although the workers of China work inhumanly hard, they eke out a miserable existence in semi-starvation. Not only are they unable to gratify their cultural needs, but they have not even time to think about them. Their living conditions are just as bitter and unsanitary. Living practically in holes in the ground, without any conveniences whatever, where a box takes the place of a table and a newspaper is used as a shet (and frequently there are no newspapers to be used at all), we find that the working class districts are so overpopulated that several familie sare forced to live in one tiny room. Young children are left by their mothers unattended at home or are taken to a factory, where the children spend their childhood. Hunger drives not only men and women but even children to seek work at the factories. The capitalists willingly employ them since female and child labor is very cheap. On the average,*40 percent of the workers employed in the Chinese enterprises are women. In the Chinese textile mills of Shanghai this percentage is 57 percent, in the foreign mills, 70 percent. In the Chinese enterprses of Shanghai the children comprise 13 percent of the workers employed; at the British mills, 17 percent, and at the Italian and French mills, 46 percent. It was the inhuman exploitation of the capitalists that compelled the Chinese workers to take up the struggle. Several remarkable vic- tories were won by the working class during 1925-27 when the revo- lutionary wave was at it sheight. Wages were increased. The work- ing day was shortened. Labor conditions were improved. The workers raised their political status. However, the victory of Kuomintang reaction put an end to all these gains. On every hand we see wage-cuts being introduced. For example, the wages of the Kwangtung ferrymen were reduced by 20 percent; dockers’ wages ame down by 30 percent; the seamen lost 10 percent; and so the list could be continued. The abrogation of pre- tmiums and rewards has also indirectly reduced wages. In Wuhan, for example, no premiums have been paid out since the cost of articles of first necessity is continually going up. Although wages are being cut, both output standards and working hours have been increased. For example, hours were lengthened by one hour and output standards increased by 25 percent on the rail- roads, and in the arsenal and cartridge factory of Kwangtung. In the textile mills the workers are now tending three looms nstead of two, and so on, But this is not all. Mass discharges and the agrarian crisis have increased unemployment. No figures are available showing the posi- tion of things throughout the country. We only know that in Wuhan there are more than 100,000 unemployed; in Shanghai more than 75,000 (which refers only to the members of the yellow and fascist unions); in Peking there are more than 100,000 unemployed. Besides this, there are no less than 100,000 unemployed seamen in China at the present time. There is no doubt at all that the workers will commence a counter attack to repel the onslaught of the bourgeoisie. Numerous strikes are being undertaken in China today to defend existing conditions. But there are also strikes to improve things. The working cl: of China is not laying down its arms. This is compelling the Nationalist Gov- ernment and the Kuomintang to endeavour to get control fo the labor movement, to get the workers to renounce a consistent class policy for “peace in industry.” Why, the.Kuomintang Government has endorsed the basic features. of the Draft Labor Law, where an eight-hour day is given prominence as well as minimum wage-rates, rest days, accouchement leave for women workers, etc. All subject to a host of reservations. It is clear that the present draft measure will never be put into execution for many a day to come. The position of the ‘Chinese workers is very similar to that of the workers of India, Indonesia and other colonial and semi-colonial coun- tries. All the workers of these countries are equally interested in improving their conditions. Their interests are one and the same, Hit! They must uni ite their forces to struggle against the present system! _ . an ttt. scsi Bil { \