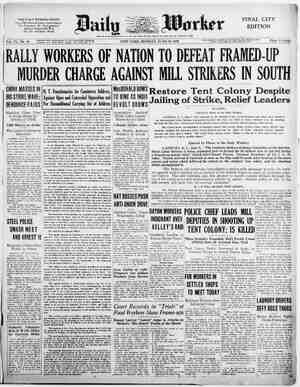

The Daily Worker Newspaper, June 10, 1929, Page 6

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

—— ; ; SRI ET TIENT iat Bs Page Six a Baily Sas Worker Central Organ of the Communist Party of the U. S. A. | Published by the Comprodaily Publishing Co. Inc... Daily, except Sunday, at 26-28 Union Ss New York City, N,’Y, vesant 1696-7-8, Cable: “DAIWORK.* Telephone St RIPTION RATE New York only): Gn six months $2.50 three months By Mail (outside of New York): $3.50 six months 2 $8.00 $6.00 a year a year 0 three months Union Square <= -. Address and mail all checks to the Daily New Worker, 26 x. York, N. A Petted Prisoner of the Parasites, r77HE Woman’s Trade Union League, that makes pretenses at being a labor organization, that is affiliated with the | American Federation of Labor, lived up to its role of pam- pered darling of the parasite rich in celebrating the 25th an- niversary of its existence. This affair was held at no less a place than the Hyde Park estate on the Hudson, of Tammany Hall’s. governor, Franklin D. Roosevelt, the same Tammany Hall that rejected every piece of labor legislation (Roosevelt himself admits 98 per cent) at the last session of the state assembly, and that is jailing daily in New York City alone scores of strikers on the picket line. One of the members of the “Honorary Committee” for the affair was Morris Hill- quit, the Socialist. The climax of this “cl lass peace” orgy was reached when Mrs. Thomas W. Lamont, the wife of Morgan’s banking part- ner who has just helped finish the job at Paris of placing the war debts on the backs of the world’s workers, handed Miss Rose Schneidermann, president of the League, a check for $30,000 to cover the indebtedness on the League’s’ head- quarters in New York City. This was cash payment to the League for driving the spokesmen of the striking Gastonia, North Carolina, textile workers out of the League’s recent convention at Washington, D. C., refusing them the right to appeal for aid in their struggle with the powerful Manville- Jenckes corporation, that also has mills in Rhode Island not far from the summer haunts at Newport of the Lamonts, Morgans and other multi-millionaires. | e occasion to make a | Governor Roosevelt seized upon th little political capital for Tammany Hall. Of this Tammany stands in great need in view of the rapidly approaching municipal election campaign. This is the only value that can DAILY WORKER, NEW YORK, MONDAY, JUNE 10. 1929 AND N ow GASTONIA ! be put on the governor’s announcement of the appointment of members to a commission “to study and report on the ad- visibility of a state old age pension law.” The governor himself in a® unguarded moment of frankness declared, “I cannot call it more than a gesture.” It is a capitalist “ges- ture” in the face of growing radicalization in the ranks of the working class, an effort to give Tammany Hall’s “labor” lackeys ‘‘one of those crumbs” (to use another of Roosevelt’s expressions) with which it is hoped they will be able to satisfy discontented workers and keep them in line at the polls, and prevent them from joining class struggle trade unions. The commission is padded with churchmen, charity dis- pensers and politicians, thus placing the whole question of old age pensions on a charitable basis, in which it is claimed that the aged will not be herded in poorhouses, but insintating that not much more can be expected. The viewpoint that old age pensions constitute a just demand on industry is en- tirely rejected. The Woman’s Trade Union League, the harlot of capi- talist politics and great business, cannot be the organizer of and the fighter for the women wage workers of this country. Neither can the W. T. U. L. and the A. F. of L. reaction wage a real struggle for:old agé@ pensions and other forms of social ansurance against unemployment, sickness and accidents. This effort grows out of the class fight waged by the left wing industrial unions under the leadership’of the Communist Party, that alone will raise the banners of class revolt against “class peace” in the approaching municipal election campaign. Furuseth Gets Kicked Again. NDREW FURUSETH, one of the energetic supporters of Green-Woll regime in the American Federation of Labor, who has followed a policy for years of destroying the Inter- national Seamen’s Union of America, rather than permit the least militancy in the organization, has just been kicked in the face again, this time by the International Labor Confer- ence of the League of Nations meeting at Geneva. Furuseth believes it is possible to get something for la- bor disguised in the role of “lobbyist.” He has been lobbying around the doorsteps of both houses of congress at Washing- ton for years without number. But without result. Now he has transferred his activities to Geneva, where he has even been denied a hearing before the committee which is dealing with the subject of loading and unloading ships. Instead he gave the committee a long typewritten statement, which was immediately thrown in the waste basket, with the refusal to allow his protest to be translated into the official languages. So Furuseth has turned to lobbying with individual delegates. The “labor” section of the League of Nations is headed by the French socialist, Albert Thomas, extreme jingo during the War, and its chief object is to misrepresent conditions in » the Soviet Union, and fight militant labor in all countries. It should have annexed Furuseth to its staff for strike-breaking purposes. Perhaps it has too many applicants from the social-democratic faithful in Europe, however, to be bothered with candidates from the United States. There seems to be too much crowding at the capitalist pie counter. In the meantime the seamen and the waterside workers in America carry on their organization activities, joining up with transport workers of all kinds for a real class struggle trade union that will fight for its demands and not beg for capitalist favors. MacDonald’s “labor” cabinet in Great Britain has been appointed and consists of an aggregation of knights, lords, millionaires and trade union traitors that should startle work- ers in all countries to do some serious thinking. It is this capitalist outfit that socialists, in every country where they are to be found, will try to peddle off as representing labor. _ J. H. Thomas, who helped break the general strike in 1926, now gets the title of “Lord Privy Seal.” He ought to make a good political Siamese twin alongside the millionaire Sir Oswald Mosley, who becomes nothing less than Chancellor‘of ‘the Duchy of Lancaster, concerning, which no worker ‘is ;sup- posed to ask questions. Sir John Sankey should have been made Lord High Keeper of the Queen's Garters, but he had to be content with “Lord Cyncellor.” the duties of which are cee Sean 3 —— = xAhe fish and he | By E. YAROSLAVSKI. | I have used the expression | “leave” although I might better have said “Decay, Dissolution of the Trot- skyist Organization.” About two- thirds of the Trotskyists expelled from the Party within recent years | have severed themselves from the Opposition, and the majority of these | have reverted to the path of the Party and rejoined the Party. Not only is the Trotskyist organi- zation in decay, the mainstay of the 'Dezists (Sapronovists) is disinte- grating, and the Mjasnikov group, | | which illegally published the news- | ‘paper “Path of the Worker to, | Power,” the journal of the IV Inter- |national, is also breaking up. | Within the last few days, the Cen- | tral Control Commission and the lo- | | cal branches have been receiving col- | llective declarations in regard to | breaking away from the opposition. | Moreover, it is chiefly workers who are thus departing from the Trot-! skyists. 1 | The cause of the breach is chiefly | | that, through the experience gained in the fight with the Party the work- | ers have become convinced that the | Trotskyists are on the wrong path. They have taken a survey, not) only of themselves, but also of the} | Trotskyists and of the Party. They | !have convinced themselves that the \talk of Thermidorian degeneration |of the Party is partly due to the former bureaucrats, who do not take into account the facts of the tense) proletarian class fight, which the Party is carrying on against the capitalist elements in the country. They have convinced themselves {that the country of the Soviets is defending the positions captured in |October, 1917, and that it is) strengthening these positions. They | have convinced themselves that the Party is carrying on an implacable, | ruthless fight against bureaucracy. Every honest proletarian is ani- mated by the desire to take an active | part in the work of socialist recon-| struction and not hold sulkily aloof and maliciously snicker over this or that deficiency, difficulty or mistake. They now comprehend the fruitless- ness, purposelessness and shallow- ness of the scholastic discussions of the opposition “leaders,” who quar- rel interminably as to the percentage to which this or that development in the country has progressed, and hold endless, dreary and phantastic speeches to the effect that the work- ing class will finally have to call upon the opposition to put things in order, ete. The workers in the Op- position looked things over and con- vinced themselves that, with these self-enamored politicians, who so lightly broke with the good prole- tarian party, they are not following the right path. Trotsky Speeds Degeneration. It should, however, be mentioned that this process, which has long | been in progress, been fomented by Trotsky’s confusion and particu- larly by two facts: the first is Trot- sky’s letter of October 21st, 1926; the second, Trotsky’s appearance in the reactionary bourgeois press. This bloc, composed of the most divergent elements and set up with- out principle, on the basis of a mere platform, fell to pieces at the first severe test. Expulsion from the Party aggravated che question of the differences of opinion within the | bloc. But the discipline in the frac-| jtion, on the one hand, and the in-| flux to the Opposition of anti-Party elements (and such there will al- dures) checked the decay. For in- stance, Trotsky’s declaration to the| VI Congress of the Comintern was signed by people, who were not at all in agreement with this document, | a fact for which documentary evi-| dence is available. (They signed on} the ground of fraction discipline.) Those who did not sign were “work-| ed” and treated as rascals: such is the “democracy” of the Trotskyists. The confused attitude in regard to the assertion that the Thermidor | in Soviet Russia had already been} |reached, awoke in the Opposition workers doubt as to whether the talk of the Opposition about the Thermidor was at all justified. The uncertain attitude of Trotsky in re- |lation to the “leftward” tendencies among the Trotskyists also disin- tegrated the opposition. And when Trotsky—after his various tackings and after loose theorizings about the tackings within the Party with the secret voting and with talk to the effect that the path of reform was one of the temporary ways,-— as one might say, the preparatory way—put the unambiguous question whether other paths were possible, when he called the Sovietistic devel- opment an “inverted Kerenskiade,” the workers immediately felt that} they were being led into abyss, that the Trotskyists were leading them on to a fight against their own class. Trotsky Unmasks Himself. The expulsion of Trotsky made the question critical. The Trotsky- ists tried all means to work upon the feelings of theif followers. They distributed leaflets; in the declara- tions and expositions of the Opposi- tion to the C. C. C. and other or- gans the*strongest words were used. But Trotsky was a conspirator. And he had to become a conspirator when everybody saw that “the king was naked.” The Opposition workers read with disgust Trotsky’s articles in the | “Daily Express,” New York Times, and other bourgeois journals. In vain the Trotskyists sought to bridge over the differences which arose in their ranks. Trotsky him- self had driven a wedge into the gap through his reactionary articles Butcher of Hungarian Workers Reviews Killers torture and murder of thousands of murderers in Budapest. Growing signs of revolt mean that the wer of the Hungar ways be in our country as long as Y aie: im ad <4 Admiral Horthy, whose ‘fascist terror government has thrown thousands of Hungarian workers into dungeons, who has lead in the ian workers and peasants Trotskyists Leave Trotsky Jin the fascist bourgeois press, and] this wedge spread and deepened the | gap. Many people then saw Trot- skyism in a new light. And every honest Opposition worker, if he does | not ask himself today the question |of his quitting the Opposition, will certainly do so tomorrow. That is| inevitable. We must dwell for a moment on the declarations of former members of the Opposition, which have been made recently. S. Baranov, former member of the Bolshevist Party since 1918, has become convinced | that “the Opposition does not help the working class with its activity nor does the Opposition help the Party to overcome the difficulties in the way of the working class, but, on the contrary, only disturbs and injures through its destructive work and shakes the foundations of the proletarian dictatorship. The Opposition will inevitably land in the camp of the enemies of the proletarian State and of the Soviet Power.” Workers Disown Trotskyism. A former worker of Factory No. 22, W. Rips, condemned Trotsky’s publications regarding the attitude of the Lenin Federation, when the llatter set up its own lists for the German parliamentary _ elections. Eleven workers from Poltava de- clared that they have completely | |broken with the Opposition and |mention in their declaration the an- ti-Soviet work being carried on by the Trotskyists. In Dnjepropetrovsk a member of the Trotskyists,. M. Gottlieb, dis- closes in the “Swjezda” the activity of the Trotskyist district head- quarters: agitation against signing the industrialization loan, attempts to undermine the collective con- tracts, agitation for strikes, perse- cution of the G. P. U., discrediting the Communists, punishment of those who leave the Opposition. In reply to his inquiry of the Moscow Trotzkyist8 why they did not send the letters of Radek, Preobrashensky and Smilga, Gottlieb was informed that “in accordance with the resolution more workers, reviewing his army |is counter-revolutionary. lideologic fight against the anti- | anti-Soviet group. | must not turn its back on those who can not much longer ort p , in powss were ieee of the All-Russian executive of the | Trotzkyists, the material of these comrades was not published, be- cause Radek—who has lately pub- lished a book and a quantity of other matter—describes Trotzky | as a Menshevik, especially in re- gard to the Chinese question; Preobrashensky and Smilga sup- | port Radek’s statements concern- ing the Chinese question. For this yeason the All-Russian Trotzky executive is not in a position to send this material, and it will not | be distributed, as it does not corre- spond to the ideology of the ‘Len- inistie Opposition’.” Oh, defenders of the purity of Trotzkyism! How beautiful is your “democracy within the party’! Again, in Dnjpropetrovsk, the workers G. Wlassoy, S. Gaponov, G. Mogilevich, Michel, declared that they have broken with the Trotzky- ists, because it is now clear to all of them that the Trotzkyist Opposition In Charkov, the declarations of the workers N, Illinski, W. Sachar- enko and 0. Simanovich were pub-| lished on March 17th, 1929, in the| “Charkovski Proletarij.” In Tiflis twelve comrades, mostly workers, and some of them mere than 15 years in industry, have) broken away from the Opposition. | In Saratov, a letter signed by six | comrades, who have broken with| Trotzkyism, has been received by) the editorial department of the “Povolskaja Pravda.” They are all} workers of the street parks. In this | case, too, it is workers who are leay-| ing Trotzky. Many Other Declarations. Dozens of other declarations have been received from -individual Trot- zkyists. We are convinced that the movement will not cease at this ini- tial stage. The more the “leaders” of the Opposition confine themselves to analysis and introspection, the less chance they will have of doing anything else as individual intellec- tuals, which many of them are. It is comprehensible that we must deal thoroughly with these declara- tions of former Trotzkyists. We de- mand definite and complete sever- ance from the Opposition, un- reserved fulfilment of the resolu- tions of the XV. Party Congress con- cerning the Opposition; we must help the waverers and not drive them away, especially if they are work- ers, if they are people who have been valuable comrades in the past, and if we are convinced that they really wish to return to the Party in order to make good their mistakes and serve the Party. At the same time, the fight against Trotzkyism should not lose its intensity. On the contrary, on the grounds of the whole develop- ment made by Trotzky and those who followed him, we must fight still more determinedly against the Trotzky atmosphere. In _ the Party tendencies, determination is the best guarantee against an oppor- tunistic conciliatory attitude towards opponents, and that is the only proper attitude in regard to devia- tions towards the Right or towards the Left. We must fight against the Trotzkyist elements, who are build- ing up their organization, just as we would fight against any other illegal But the Party break with the Trotekyists and re- turn to the Party. The resolution of the XV. Party Congress is still valid and the Party need not depart from] this resolution a eRe ~ Pe |\CEMEN By FEODOR GLADKOV Translated by A. S. Arthur and C. Ashleigh All Rights Reserved—International Publishers, N. Y. Gleb Chumalov, Red Army commander, returns to his town on the Black Sea after the Civil Wars to find the great cement works, where he had formerly worked as a mechanic, in ruins and the life of the town disorganized. He discovers a great change in his wife, Dasha, whom he has not seen in three years. She is no longer the conventional wife, dependent on him, but has become a woman of de- cided independence, with a life of her own, a leader among the Com- munist women of the town. Gleb wins over the workers to the task of reconstruction and gains the support of Badin, chairman of the District Executive of the Soviet. Badin and Dasha go on an important mission to a place at some distance from the town. i 4 * . * NE of. the two boys shcok his tatters and took to his heels like a running scarecrow. Dasha started laughing and broke the bread into two pieces. ! “But do come here, little piggies! the Home. Here, there’s a piece for each of you. cowards you are!” She was so jolly and friendly (if it weren't for the red scarf!) and the golden bread should be sweet as honey. The boys glanced sideways at each other, and approached slowly and furtively, stretching out their hands from as far away as possible, She gave them each a piece of bread. She wanted to pat the tangled hair of the second one. But he shrieked and rushed away in terror. Nurka was in the Children’s Home, but was she happier than these naked beasts? Dasha had once seen Nurka with the other children digging in the rubbish heap behind the dining-room of the Food Com- missariat. It had seemed to her then that her daughter was already dead, and that she, Dasha, was no longer her mother; that Nurka had been abandoned to hunger and suffering through Dasha’s fault. It seemed that her occasional caresses in the Children’s Home were not the fondling of a mother, but of a sterile blooming. She had carried the little girl in her arms right to the Children’s Home and her heart was ravaged with pain, I’m not going to take you to But what little sot @ ey was standing near the carriage now, his black leather coat shining. He looked straight at Dasha from under his bony forehead. “Get in, Comrade Chumalova, and we'll be off.” He did not wait for her but clambered in, and all the springs creaked under his weight. Dasha sat beside him and felt the unyield- ing pressure of his hip. Badin took more notice of her; he was re- served, cold and severe as usual. “It’s impossible to make this journey in an automobile. Even in this carriage we shall only go at a snail’s pace in the mountain. Are you afraid of bandits? I’m only taking my revolver with me. Per- haps I should have arranged for some Red Cavalrymen to accompany us?” Dasha glanced at him. Was Badin himself afraid? But she could not make out. His face was firm and immovable as always—a face of bronze. “Just as you wish, Comrade Badin. If you are afraid, order an escort. But I’m accustomed to be sent away without an escort.” “Right then! Off we go, Comrade Yegoriev!” Comrade Yegoriev, frightened, turned round two or three times looking at Badin, longing to say something, but unable to get it out, Then he clucked to his horse, blew his nose and gathered up the reins, ¥ HILE they were driving through the town they were silent and it was unaccustomedly pleasant and gay for Dasha to swing along so comfortably and easily. On the street they saw Serge. He inclined his red bald spot to her, and his ruddy curls shook like wood shavings. Shuk met them also and stood still astonished with a confused expression on his face. Badin’s thick lips curled with a disgusted smile, “I can’t stand that type.” “Comrade Shuk? Really? But he’s a good turner and a con- scientious Communist. He doesn’t like our generals and bureaucrats and worries a lot about it. “Shuk is simply a good-for-nothing and a disrupter. should certainly be driven out of the Party.” “No, Comrade Badin. Comrade Shuk is good and he speaks the truth. And when he finds something out, you’re all angry. Is that right? Isn’t it true that all you responsible Party workers. see the working class only from your private workrooms?” “You're mistaken. The private office of a responsible militant is nearer to the working class than are such wranglers as your good Comrade Shuk; because everything passes through these offices, from complicated questions of state to the smallest details of daily life. It was in the private bureau of a responsible Party worker that I made the acquaintance of your husband.” He laughed, not with his customary laugh, but like the roll of a* drum; and his words and his laugh were alike. This laugh of Badin’s always disquieted Dasha. F * * * Such fellows “ * * eS town was already behind them. They were driving through the ravine; on the left the mountain slope was covered with vineyards; on the right was a wood still bare and blue, dusky, with burst buds decking the branches like cobwebs. The trees were moving: the front rows retiring, and the succeeding rows going forward with Dasha; and it seemed that. the wood was revolving, in commotion, accomplishing some immense labor hidden from human eyes, “Well, and how is your homelife getting on? On the one hand marriage duties: a common bed and dirty linen. On the other hand Party work. And I believe that you have also offspring. You'll have to choose between the Women’s Section and home cares. No doubt your husband is already making specific demands. You've a big- fisted lad there.” Dasha shrank back in her corner. her heart to her head. “My husband lives his life and I live mine, Comrade Badin. We're Communists first of all, and not loafers.” Badin’s laugh again drummed out. He placed his hand on Dasha’s knee. “You speak like all women Communists, but the bed is the bed all the same. Although it sounds more sincere from you than from most; from you it comes from the heart. I know already how difficult it is to find common ground with you.” Dasha pushed his hand from her*knees and drew herself as far away as she could. “Comrade Badin, Communists can always meet on common ground in their common work.” Badin again became reserved and heavy as iron. He stirred away ren Dasha and she caught a flare in his eyes which affected her pain- ‘ully. “Sit more comfortably. I’m not going to eat you.” He twisted his lips in an offensive smile. ‘ “Tm not afraid of your teeth, Comrade Badin: We know each other well,’ Hi i * H Kaneda journeyed in silence, each looking away on his or her side of the carriage, along the ravine, where the morning was darkened by cliffs and thickets, where brook murmured and colored boulders lay. \ But Dasha sensed how Badin’s blood leaped, and how he hid the clamor of his heart with a broken cough. She knew he was fighting within himself, without having the strength to throw himsejf violently upon her. She knew that he was not yet tamed; when he was close to her a frenzied beast stormed in his eyes. If at this instant he was not going to throw himself upon her, he would seek another moment when he would be stronger than she. She felt her blood throb with sus- pense and could not conquer her anxiety, her fear for her own strength. If it were to happen now, she could not resist his muscles of a mad- dened bull; the unsteady swaying of the carriage over the rutted road prevented her bracing herself firmly to resist him. The ravine was three miles long, and then came a smooth, wide road through the valley. At the end of it lay the Cossack town, at the foot of the hills among gardens and orchards. The mountains rose with cliffs and steep, brown slopes to the sky. Cliffs and rocks flamed in the sun; the twisting ridges and heaps of stone and slag seemed to flow like streams of molten metal. Down | below the hovering misty darkness quivered over the woods and | thickets. Above the mountains and woods streamed the blue sky, | and the clouds stood in it like ice-bergs. The wood down below seemed to have been hurled from the steeps: impassable, and the night crept, fertile and moist, through the dense forsts, rustling with dim, foreboding, 5 A wave of disquiet flowed from * *