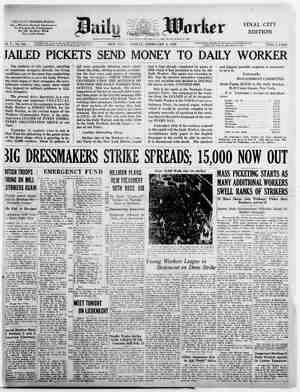

The Daily Worker Newspaper, February 8, 1929, Page 4

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

ee Page Four DAILY WORKER, NEW YORK, FRIDAY, Fe BRUARY 8, 1929 Baily 328 Worker f Central Organ of the Workers (Communist) Party SUBSCRIPTION RATES: By Mail (in New York only): $8.00 a year $4.50 six months $2.50 three months By Mail (outside of New York): $6.00 a year $3.50 six months $ Address The Daily Square, } Published by the National Daily Association, Stuyvesant DAIWORK.” MINOR to DUNNE ..... . Editor ss. Editor ROBER WM. F. Who Are the Enemies of the Needle Trades Workers? At ten o'clock Wednesday morning many thousands of needle trades workers poured out of the dress shops in New York on a strike which promises to begin a new period in the lives of the oppressed workers of the entire needle industry. Within an hour after the needle workers were out on the street determined once and for all to smash through the terrible scab conditions in the dress industry, we hear from Mr. Benjamin Schlesinger, yellow socialist and president of the bosses’ scab union in the industry. Did Mr. Schlesinger say anything about the insufferable conditions, the miserable wages and other hardships which have driven the workers to fight? No. Did Mr. Schlesinger—the alleged “labor” leader =—express any wish that the workers upon whose union-dues he lived so many years, should win an improvement in these conditions? No. Schlesinger, head of the ‘bosses’ company union, had only one idea to express: “If any effort is made by the Needle Trades Workers to « annoy” (the scabs) “in the shops which have signed up with us” (meaning with the scab company union), “we will make a con- certed effort to have the POLICE protect the shops.” At the moment the yellow socialist Schlesinger was ut- tering this unspeakable treason, the police-allies of Schles- inger and the bosses were at work committing the very crimes which he threatened. For asking the workers in the Bermand shop on West 24th St. to “come down” on strike, Henry Rosemond, a colored fur worker, one of the leaders of the strike and a member of the Joint Board of the Union, was hit over the head with an iron pipe, stabbed and knocked un- conscious by the police accomplices of Mr. Schlesinger. Simultaneously the police were busy arresting members of the Union for distributing the strike call. For a long time we have been pointing out that the so- cialist party and the trade-union bureaucrats have become in fact “a party of the police and strikebreakers.” Already a thousand times this has been proven. When Schlesinger rushes to the capitalist press—even before the employers do —to denounce this strike for the right to live, as “an out- rage,” and as “scandalous,” it is only another proof that the right wing gang is precisely on the level of the worst pro- fessional strike-breaking thugs who hire out by the day at strike-breaking. The difference, if there is one, lies in the cowardice of the “socialist” bureaucrats who dare not meet the workers on the picket line, but who merely sit in luxuri- ous offices to slander and threaten the workers. This proto- type of yellow bureaucrats not only slanders the workers who are on strike, but also attacks the Workers (Communist) Party because it is the one and only party of our class, the only party which does not betray the workers. His hatred of the needle workers who threw off his treacherous leader- ship is exceeded only by his hatred of the government which the workers have set up for themselves in the Union of So- cialist Soviet Republics. He lies about the strike, he urges the police to crack the heads of the workers for the benefit of himself and the bosses, and he spews his venom upon the workers’ cause on a world scale. This is not Schlesinger alone who speaks. It is one yel- low “socialist” bureaucrat speaking for the whole aggrega- tion of the socialist party and the crooked, treacherous, swindling bureaucrats and the bosses. Ts there a single worker in New York who doubts the guilt of this callous bunch of strike-breakers? If even one honest worker still doubts that Schlesinger, the socialist party and the “Forward” are in an outright conspiracy with the scab bosses, let them read the following words of F. C. Rogers of the Wholesale Dressmakers’ Association, published Wednesday in the bosses’ newspaper “Women’s Wear.” Speaking for the scab dress employers, Rogers said: “We have perfected an arrangement with the ‘Rights’ where- by the workers will be swung into the vacancies with little delay. Through cooperation with the ‘Rights,’ the production of the as- sociation members and any of those firms calling on the associa- tion for assistance, will be maintained.” So the treason of the “socialist” strike-breakers has be- come so brazen that they do not even conceal it, as far as the bosses’ trade paper is concerned. They only lie (very shallowly) in the “socialist” papers—meant for boobs to read. Who are the needle workers’ enemies in this strike? ‘Answer: The bosses AND the “socialist” trade union bureaucrats. The bosses and the bureaucrats of the A. F. of L. com- pany union AND the police, AND the courts AND the state * power of the bosses—all these are the forces lined up against the workers. But the workers have a new and more powerful union weapon than they ever had before. The new union is the workers’ own union—not the bosses union, which the old Sigman-Schlesinger scab union is. It is not a narrow craft union, dividing the workers, but an industrial union uniting the workers, and which will ultimately unite all the workers of the entire needle trades industry. It has a new leader- ship, chosen by the workers themselves, held to their duty by the workers, and subject to recall by the workers if they do not perform their duties as militant leaders of class struggle. The workers have confidence in this leadership. ‘Again we say that the dress strike must not be con- ceived or conducted as merely a craft strike in a single branch of a light industry. Industrial unionism and the class strug- gle must be the strong guiding line in this strike. The future and the present needs of the dress makers and of the needle workers and the working class must be held in view at every ment. Then we will see that the dressmakers’ strike in few York can blaze a pioneer trail for American labor. Don’t forget who your enemies are! Straight ahead and this ‘nied strike of the new Needla Trades Workers’ In- bi ion, While Packard Prospers .. ROBERT L. CRUDEN. e “Detroit Free Press” has just meed that “Directors of the ard Motor Car Company clared an extra cash dividend 0: |per cent on the com common |stock. . .. This e: disbursement pany calendar I can appreciate this after working in the factory several months! Ten Per Cent Hired. After trying every big plant in town at least once I got in Fack- jard’s as ventilator assembler. Out jof the jrooni while I was awaiting finai in- | spe ction there were about 20 taken jon. This was not uncommon at the time the Detroit Employers’ Asso- |ciation was announcing that em- ployment had reached its highest peak in Detroit's history. I have gone «around to factories o'clock in the morning and men there who had been wait- ing from Pour, so that they would be first in line when the office epened. Just what they got by that I don’t know, for all that happened was that a clerk came out, waited until you passed before him and shook his head. Never a chance to ask a second time, for the man back of you pushed you on! Bottom Wage. At the Chevrolet plant one after- noon T watched 800 men go through in this manner without one man be- | ing hi I was very lucky to “land” a job at Packard! I was hired in at 52 cents per hour and I almost immediately found that I was the lowest paid in the gang. Other workers endeavered to explain to me that it was because I was new; but that lost color when a fellow 50 who passed through the | The Daily Worker hopes that contributions to help in its present crisis will enable us to resume printing the Fred Ellis cartoons, beginning tomorrow. The paper is far from being out of danger, however, and the need for rushing contributions to its aid is more urgent than ever. THE DAILY WORKER, | 26-28 Union Square, New York. | The Slaves Who Wait to Be Hired; A Scheme to Break Unity; Speedup; Starvation Wages he demurred he was told that there were plenty outside just begging to co it for 45 cents without the bonus. He got transferred to a job at 54 cents and bonus. On our job the lowest rate paid had been 58 cents; all new men were taken on at less than that amount. Yet this same company’s personnel manager had the gall to tell the Student Research Group in Detroit that there had been no general wage-cut in Packard for five years! Minus Bonus. The bonus also began to act strangely after “vacation.” No one knows how it.is reckoned, and after “vacation” it just didn’t come. Our |gang had drawn a bonus of 20 per }cent on 100 jobs a day; we put out |180 jobs a day and got a 2 per cent | bonus once in eight weeks! The wet- sanders and polishers had also been making high rates; with increased joutput they were now getting less j than 10 per cent. | Low Pay for Trade. Evidently the company didn’t find that enough to bolster up an extra dividend, for they stopped the wage- vaise which was due immediately |after vacation. Compared to other plants, their wages are low. | Poiishers get 64 cents at Packard. Sprayers, working under conditions |menacing to their health, get 65 jeents for work for which in some | other plants they get 80 cents. In jthe oil-sanding department the |workers have to get rubber boots ‘costing $5, and they have to pay \this out of their wage of 60 cents hired after me got more than I did. |an hour—and they also have to pay I became suspicious when I found | doctor bills for the skin diseases that since “vacation” a lower wage- | they contract due to the oil used in scale had been in force, I soon the operation. found out. Men Quit. To. Break Unity. While speed-up in Packard is not The wet-sanders were being sped- | so bad as in other places, I found it up; men were leaving wholesale. | fast enough for my liking. I also The workers who could not afford noticed that the polishers’ and wet- to quit determined to get together | sanders’ gangs never were in full and protest to the boss. All those | strength. One line in particular we making 54 cents an hour joined |called the “Visitors’ Line,” because them; those making 68 cents an hour | no man stayed on it more than half politely told them to go to hell. By a day. The turn-over was huge; such a simple precaution Packard} ne could almost say that the en- sterilizes organization at its source. | tire department’s personnel changed New men might be paid “hi er” | every two days. Even a belated than mes who had been on the job l|wage-raise could not prevent the longer, but the “high” rate was ac- | trek of the workers. You can judge how hard a job it is when you re- member that these men know what lit is to be out of a job in Detroit! Painful Work. The work consists in rubbing the | auto body with wet, fine sandpaper, so that all your energy has to be }concentrated in your hands. The {strain on the arm and hand muscles lis tremendous. On the polishing job the swing of the body causes intense pain. After about six hours the men slow down, “all in’; but still the lines crawl relentlessly along and the foreman comes strid- ing down, “Come on now, boys, get on the job! Snap out of it!” On our job output was increased daily and not a man was added. Naturally, we worked like fiends, |slways under the displeasure of the general foreman, who did not like the “quality” of our work. Besides, our gang was never complete, thanks to fatigue; to make up for the in- complete gang, they made us work Hi hours a day, Big Boss a Tyrant. We all feared and hated the “big | boss.” Our own foreman was a fine, likeable chap who was himself junder fire for not speeding up the men under him. The general fore- man, the “big boss,” was called “the slave-driver,” and that fits him. He would not allow us enough men to do the jobs right. He fired the best man on our gang for talking back to him and he threatened to fire an- other one for explaining why we could not do the jobs well. When I asked him why he criticized me for something I’d never seen nor heard of before he nearly exploded and told our foreman that he was go- ing to “fire the whole god-damned bunch!” The men don’t stand up against the bosses, for an integral part of the “American” plan is the blacklist, in Detroit, as elsewhere. When the boss comes around they speed-up, speak to no one and try not to draw his attention. If he leurses them, they stand for it. Discontent. There is real discontent. The older men are angry because they have received no raises; the newer men are resentful because they are tually lower than the rate prevail- | ing before the annual compulsory | “vacation.” Youth is Penalty. | On the body line wages had been cut from 70 cents to 54 cenis per | hour; top-trimmers found that new | trimmers were being hired in at 54} cents where formerly they had 1 ceived 65 cents. A young fellow, 18, | was getting 9 cents an hour less | than others just because he was| younger. Another man, who had} been with the company since 1915, told me how he had gone back to \his job, for which he had been get- | |iing 60 cents, and had been offered 48 cents an hour with bonus. When By A. B. MAGIL. “You can’t lose what you haven't got. It looks to me as if we’re go- ing to win this strike!” | Rose Medoff, dressmaker, speak- ing. She works in the Deutsch and |Klein shop at 115 W. 30th St. That lis, she did until 10 o'clock Wednes- |day morning, when she came out on | strike with every worker in her shop ‘and helped pull out most of the ether shops in the building. Her |levflets,” one of them said. And the eyes flashed and she laughed con- | police -be damned! \fidently as she spoke. ore eke | I met her as she was walking] In the garment center, particu- with other strikers to Irving Plaza. |larly between Sixth and Bighth She was selling the Daily Worker Aves., and above 24nd St., workers and holding up a copy with the big | throng the streets. They come down headline; ‘Dressmakers’ Strike To-|in groups from the shops and wait |“Can’t Lose What You as 12 workers discovered yesterday when they were distributing the call for the dress strike. But the police couldn’t scare them. They cheered land sang as they were arrested. “We're sorry we didn’t have enough Slavery at the Belt; in an Auto Plant day!” so that everyone could see it. “Are you selling many copies?” T asked. She laughs. “Over a dollar and sixty cents worth! I was selling them at 53rd and Broadway early this morning, and a cop came over to me and tried to chase me away. But I put it over on him, alright. If I was giving the Daily Worker away free he could arrest me, be- cause that’s like distributing leaf- lets. But I was selling them and selling a lot, too, s0 he couldn’t touch me, the poor thing!” She was right. If you distribute leaflets, and they happen to be leaf- lets calling workers to militant ac- tivity, you are offering insult and injury to the majesty of the law, for the workers in the other shops in their building. Strike! Every- body out! The fight is on. se * In a shop on 38th St. two pressers are loath to go down. The boss comes over and begins ingratiating himself with the two faithfuls. He thinks it’s a good idea to attack the left wing. He does. The two press- ers drop their work, grab their hats and coats and-—the shop is down 100 per cent. * * ° At the office of the union at 16 W. 2ist St. workers are milling sround. “And we told the boss that we're all going down together!” $24 A middle-aged worker is speaking | workers. Thunderous applause greets Snapshots of First Day of Dress Strike Haven’t Got”; Strikers Show Determination in Fight to a group of fellow-workers. Among the listeners is an old man with a beard, his eyes lit with a happy smile. A man comes in sell- ing newspapers. “Hey, there, got a Forward?” Everybody laughs. Outside’ workers are marching past, singing “Solidarity Forever.” The fight—the fight of the classes is on! *. * * In the afternoon, meetings in the strike halls. Every hall is jammed, hundrede of workers are forced to stand. I park myself somewhere in Webster Hall. “Feb. 6, 1929, marks a new page not only in the history of New York labor, but of American labor.” Wil- liam W. Weinstone, district organ- fzer of the Workers (Communist) Party, is talking to the workers. His words are a clarion call ‘o struggle. “We have seen the united front of the bosses, police and so- cialist party union officials against the workers in countless struggles. Now the workers must estabiish a united front of their own.” He tells of the role of the Com- inunists in the struggles of the getting less than the men before | |them; all are inflamed because of the bonus gyp. -A man who had | been given a watch by the company for 10 years’ service almost tear- fully protested to me, “Wot dey want give us gold vatch for? Dey eut vages for vatch.” Another, more violent, “This watch ain’t worth a damn! And d’ye see them bodies ?—Packard junk!” A south- erner told me, “Yo cain’t save a cent in this damn shop,” and a younger fellow, sore at the bosses, chimed in, “Yeah, an’ if we only had a union them god-damned bosses wouldn’t jbe_so smart in bossin’ us around.” Want Union. | Every issue of the “Auto Work- ers’ News,” organ of the Auto Workers Union, was greeted with enthusiasm. At lunch time we'd sneak in behind bodies and read and discuss it. Out of all the men I talked to through all the body de- partment I found only two opposed to unionism. We talked politics, of course, for I passed out oropa- ganda. They were cynical regard- ing the socialist party, counting it in the same boat with the cohorts of Tammany and Teapot Dome; and they thought of the Communists as “Reds” from Russia—although they had more hope in the Workers’ Party than in any other. One mild, Scotch fellow said to me: “Over in the Old Country I was a member of the social-democratic |federation, but here I am more a Communist than anything else.” A. F. L. “Not Ready.” With this throbbing discorttent before me I dashed off a letter to the American Federation of Labor, asking for information and propa- ganda for the auto workers. I am still waiting for a reply to my let- ter, but two weeks ago I sent the same inguiry to President Green and he writes me that “the Amer- ican Federation of Labor is not yet ready to make a formal report of its endeavors to organize the auto- mobile industry. We are still ac- tively engaged in this work in dif- ferent sections of the country, but as you can ‘appreciate our activities jare greatly restricted for financial jteasons.” This bit of boloney comes |two years after the Detroit conven- | tion, when fat boys of the A. F. of |L. made their bluff at organization |by passing another resolution. So Packard, like all the rest of the motor corporations, goes on piling up profits, speeding up the workers and cutting wages. The workers are waking up; faced with a declining standard of living, and | worn out and angry, due to the ner- vous and physical strain of the speed, they are slowly developing a collective consciousness. The cam- ‘paign to organize the auto workers, jlaunched by the Auto Workers | Union, should have a quick and | warm response from the workers. | The workers in Packard’s, and all other big plants, will welcome the speakers and the literature. The workers are getting ready to make | of Detroit one of the mosi important oeio battlefields in this coun- try. his concluding words: “We fight against the sweatshop, we fight against the capitalists; yes, we fight for the cverthrow of the entire cap- italist system and the establishment of a workers’ and farmers’ govern- ment in America.” + 2 * Other speakers, The words of Ben Gold are fire, He is tired, he hasn’t slept all night, he has been on the go for hours without rest. But his words sweep on with tire- less eloquence. They grip his hear- ers, the workers are filled with his earnestness, his determination to fight on until victory. Louis Hyman, president of the in- dustrial union; Charles Zimmerman, M. J. Olgin, G. Oswaldo, Italian or- ganizer; they bring a fighting mes- sage and the workers are roused to action. To the picket lines! “You can’t lose what you haven’s got.” The fight is on—and the workers will win! LEJUNE RETIRED, WASHINGTON, Feb. 7.—Major General Lejune, commander of the U. S. marine corps, hero of a dozen wars of conquest for his Wall Street masters, retired today. During the world war Lejune commanded the Second Division, made up mostly of marines, and by use of the best press agents in the army, managed to popularize even the marines. We Ay Copyright, 1929, Publishers Co., Inc. by Internatio; BILL HAYWOOD’ BOOk The Fight for to Make the Eight-Hour Da Effective in the Denver Smelters; a Monument to the W. F. M. All rights reserved. Republica- tion forbidden except by permission, In previous chapters Haywood wrote of boyhood years among the Mormons; his youth and young manhood as miner and cowboy in Nevada; mining at Silver City, Idaho; his rise to Secretary-Treasurer of the Western Federation of Miners; the fight of the W. F. M. against the open-shop Citizens’ Alliance at Telluride, Colorado. Now go on reading. te? a ee By WILLIAM D. HAYWOOD. PART XXXI. r is seldom that organizations find their monuments already buil but this unusual thing happened to the Western Federation of Min ers, The monument had only to be named. One of the desperat struggles of the W.F.M. was with the gigantic Guggenheim Corpora tion and other smelting and milling interests in Den- ver, in connection with the working hours of smelter men. It had taken more than two years of persis- tent agitation to get sufficiently well organized to demand that the eight-hour law of the state be com- plied with. This was to be the first step. We had been hoping and working for the strength to strike to enforce this law. A general meeting of smelter men who were working on the day shift was held in Globeville town hall on the night of July third, 1903. This. meeting was to be the deciding factor and to give the defi- nite answer as to whether there was going to be a strike. Moyer wa in Butte, Montana, I telegraphed him about the growing demands o the part of the smelter men for a strike, and of the meeting that wa to be held. To my surprise, he wired to “postpone action till I re turn.” Postponement seemed to me inadvisable, if not impossible, said nothing about Moyer’s telegram to the workers, and the progran went ahead without a hitch. However, Moyer arrived in Denver jus in time to take a desultory part in the meeting. The men were ii earnest and enthusiastic, not to be tempered with any idea of delay They were ready to strike, and wanted to do it at once. There wa: much rough and ready discourse about the indignities heaped upor them, the injustice of the long hours of work, the enormity of thi “long change shift,” in which a man worked twenty-four hours throug} when changing shift at the end of each two weeks. Some of the workers assumed the high moral ground of compell ing the smelter companies to comply with the law and constitution o: the state, which made it mandatory that all men employed in certair designated hazardous or unhealthful occupations, including smelte: men, should not labor more than eight hours. One contended that th long hours they were: working gave married men no chance to get ac quainted with their families. Their children were asleep when the} left home for work in the morning, and were ready for bed when they returned at night. The general spirit of the meeting showed a1 awakening of minds long dormant through the inhuman hours of harc work, and of an active, interesting period for the smelting companies while the strike lasted. It was decided that no one should leave the hall. At the hour oi midnight a resolution declaring the strike was adopted unanimously Outside, cannons boomed, anvils exploded, whistles blew. Fire: crackers were popping. It was the fourth of July. The noise anc bedlam was the beginning of the celebration of the Declaration of Independence, *_ 8 8 What a hollow mockery! What a miserable sham it seemed! Ir this stuffy little hall in the capital city of Colorado the spokesmen of thousands of wage-slaves were making their crude preparations for a bitter struggle, not for independence but for a shorter work-day. The fourth of July or any other holiday meant little to the smelter men, for their work must never cease. The fires that melted the ores, like the fires of hell, must never cool. There were no rest days, nc Sundays, no holidays. These were the men with whom the real battle was to be fought. They wanted relief from a most vicious system of exploitation by a giant corporation, the head of which was Simon Guggenheim. It was terrible to realize that most of these smelter workers now striking, fighting for the betterment of themselves and their families, gave little thought to the terrible injustices imposed upon the people of the United States by corporations, bankers, politicians, who have transformed what might have been a free republic into a bestial slave- shambles. Certain it was that these strikers would face privation and imprisonment. They would have to contend with scabs, detec- tives, courts and perhaps soldiers, they would have insults and in- dignities heaped upon them, injunctions would be issued against them, and yet some of them would hurrah for the fourth of July! nme eae The strike was to begin at once, as soon as the men on shift could be notified. The men knew that to be forewarned was to be fore- armed. The first knowledge that they proposed the company should have would be when the smelters closed down. The men left the hall in three divisions, the Argo smelter men first because that was farth- est away, and then the Globe, the Grant smelter men last. It was in- tended that the calling of the strike should be simultaneous in the three big smelters. There were to be no parleys. “Quit work. Quit now. Strike!” That was the order. It was obeyed on the instant. The bosses were in a flurry, “Keep up: the fires! The furnaces will freeze!” But their orders were not obeyed. The strikers shouted as they hurried about in flare and shadow, “Strike! Strike! The strike is on! Strike while the iron is hot!” The smelters were in the suburbs of the city. It was some time before the patrol wagons with the Denver police arrived on the scene, and when they got there, there was little they could do. The men had quit work, the strike was on, the battle had begun. At the Globe and Argo smelters, the bosses and office staff and as many officials as they could call up by telephone, managed to keep the fires going somehow, but at the Grant smelter the furnaces froze, the fires cooled, the. metal and slag congealed. These furnaces never blew in again. The smokestack of the Grant smelter is one of the highest in America. Since the fourth of July, 1903, no smoke has curled from its top. It stands, let me dedicate it, a monument to the eight-hour day for which the Western Federation of Miners so val- iantly fought. * * * At the meeting of the miners’ committee in the Senate Chamber and the assembly hall, I described the conditions of the men who were working in the smelters, and the kind of homes they lived in, and com- pared a striker’s home with the palace of ex-Governor Grant, who was one of the principal owners of the Grant smelter. There had been a description in the papers of the Grant home and some of the mar- velous furniture it contained. I said that a single piece of Grant’s furniture would buy a dozen such houses and furniture as the strikers had. I compared the rustling silk of the wives of the smelter owners with the clatter of babies’ skulls; the infant mortality of the <melter district was, higher than in any other part of the state. After I was, through, ex-Governor Grant came to me with tears running down his cheeks and said that he himself was willing to have complied with the constitution of the state and would have tried to make the conditions of the men around the smelter better than they were, but that the company prevented him from taking any individual action. I had just finished talking with Grant, when Manager Guiterman’ of the American Smelting and Refining Company, Guggenheim in- “terests, came up and said to me: “Mr. Haywood, we were taken by surprise when the strike was declared in our smelter, as Mr. Moyer had told me that there would be no strike without notification to the company.” I was astonished at this, as I did not think it possible that Moyer had intended to act as a traitor to the organization. He knew that he was not authorized by his position as president of the W.F.M. to make such a promis#, either to Guiterman or to anyone else. He further knew that the company would receive no notice if the workers could possibly avoid it, as they intended to make the strike effective. I did not take Guiterman’s statement seriousl}; it seemed untenable and I let it pass as a slander. z i In the next instalment Haywood writes of the fight of the W. F. M. to make the cight-hour law effective in the ore-mills and mines of Telluride, Colorado, in 1903; the lockout; Bulkeley Wells, leader of the Citizens’ Alliance; Governor Peabody ships in militia; martial law as it works in Colorado, n