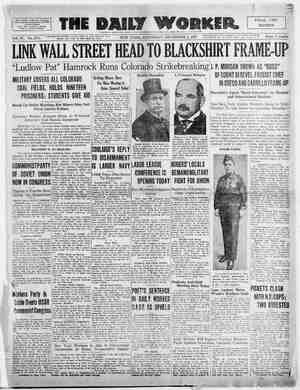

The Daily Worker Newspaper, December 3, 1927, Page 7

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

Frontispiece drawing by the noted Mexican Communist artist, Xavier Guerrero in the current issue of “The Communist.” la Russian Revolution in Literature and Art INCE art'is an expression, an emo- tional systematisation, of feeling and experience, it was natural that P oe 4 |tern of his art, like a drum, served the Russian Revolution should have a profound “influence in’ this sphere. The emotions: aroused by a. social conflict as deep as that of 1917 are generally richer and more profound than the emotions of individual ex- verienee; and the pains and the hero- ism, the uprooting ‘of old relation- ships and affections of this period, were bound te enrich artistic experi- enée, and. the sudden revolutionary break with the past to loose a flood- tide of creative energy, In the hectic days of hunger and civil war there was little pause for finished artistic creation. Emotional energy was fully absorbed in the rhythm of machine-guns or of the tammers ih the railway shops; it had no- room: forthe rhythm of the ‘son- net. The artist was employed to rush out posters overnight,. to splash illu- minated slogans on pavement and boarding, to compose political lam- poons or to sing of the Revolution in ballad and verse. The staccato pat- to whip tired emotions into activity, to add strength and pungency to mass appeals. In the realm of the theatre there sprang into being the revolutionary satire of the workers’ theatres, the creations of the Prolet- cult theatre, and later the “Living Newspaper” of the “Blue Blouses”— half-cabaret shows, — half-“Chauve Souris”, given by troupes of actors who toured the factories and workers’ clubs, illuminating and explaining the topics of the day in verse and song and ballet. Art was used for direct and. immediate ends; and what this early work (which was often crude. and hasty) lacked in form and finish, it gained in vitality, in originality and in riot of color and rhythm. Moreover, it was close to the masses and was a direct product of their own mass experiences. Serie 34. 35. Piano Op. 69. chestra, Op. 38. Op. 55, for Violin and Piano, BEETHOVEN: ( BEETHOVEN: BEETHOVEN: EETHOVEN: 9. KEETHOVEN: . BEETHOVEN: . BEETHOVEN: . BEETHOVEN: . BEETHOVEN: . BEETHOVEN: 57, for Pianoforte. a AG AO OUT TSCHAIKOWSKY: Trio Artist,” Op. 50. Masterwork | . BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 2, in D, Op. 36. . BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 8, (Hroica) in E Flat, BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 4, in B Flat, Op. 60. BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 5, in C Minor, Op. 67. . BEETHOVEN: Quartet in F Major, Op. 59, No. 1. BEETHOVEN: Quartet in E Minor, Op. 59, No. 2. . BEETHOVEN: Quartet in C Major, Op..59, No. 8. . BEETHOVEN: Trio in B Flat, Op. 97. . BEETHOVEN: Sonata in:A (Kreutzer Sonata), Op. 47, ( Sonata quasi und fantasia, (Moon- light Sonata), Op. 27, No. 2. ( Sonata Pathetique, Op. 13, for Piano- ( forte. 8 Quartet in F Major, Op. 185. Quartet in F Minor, Op. 95. Symphony No. 1, in C Major, Op. 21. Quartet in C Minor, Op. 18, No. 4. Quartet in B Flat, Op. 18, No. 6. Symphony No. 6 (Pastoral) in F, Op. 68 Symphony No, 7, in A Major, Op. 92. Symphony No. 8, in F, Op. 93. Sonata Appassionata, in F Minor, Op. Of All The Great Composers BERLIOZ: Symphonie Fantastique, Opus 14. { BRAHMS: Quartet in A Minor, Opus 51, No. 2. | 86. BRAHMS: Sonata in A Major, Opus 100, for Violin and BRAHMS: Sonata in F Minor, for Pianoforte, Opus 5. BEETHOVEN: Sonata in A, for ’Cello and Piano, BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 9 (Choral).° SCHUBERT: Quartet No. 6, in D Minor. . SCHUBERT: Symphony No. 8,in B Minor (Unfinished) . MOZART: Symphony No. 35, in D, Op. 385. . MENDELSSOHN: Trio in C Minor, Op. 66. . SAINT-SAENS: Concerto in A Minor, ’Cello and Or- 3. BEETHOVEN: Quartet in G Minor, Op. 18, No. 2. . DEBUSSY: Iberia: Images pour orchestra, No. 2. ° . WAGNER ALBUM No. 1. HAYDN: Quartet in C Major, Op. 54, No. 2. BEETHOVEN: Quartet in B Flat, Op. 180. MOZART: Concerto for Bassoon and Orchestra, Op. 191. . MOZART: Symphony No. 41, in C Major (Jupiter). “To the Memory of a Great WE WILL SHIP YOU C. 0. D. PARCEL POST ANY OF THE ABOVE MASTERWORK SERIES OR WE WILL BE MORE THAN GLAD TO SEND YOU COMPLETE CATALOGUES OF CLASSIC AND ALL Hatt FOREIGN RECORDS. _ European American Record Co. 86 — 2nd AVENUE (Dept. C) NEW YORK CITY. 1 Later, men who had passed through the fire and ‘thunder of the heroic days had respite to frame in concrete images the torrent of experience which they had undergone. They had not merely shouldered a gun like} mercenaries: they had taken part in| the building of a new world; and the experience to which they had to give expression was in consequence excep- tionally rich. These writers had not self-consciously to “create an atmos- phere” like the bourgeois litera- jteur: the deep emotional imprint of , that experience, compelling expres- \sion, forged a form and style for it- |self from its own inner rhythm. Moreover, these experiences were so- cial experiences, in which the individu- al had been subordinated to the mass, and individual conflicts and emotions | had been absorbed and merged in mass struggles and emotions; and the new art which resulted was, conse- quently, both more complex and pow- erful and of more universal mass ap- peal. Of works of this kind we have only a few in English. There is Libedinsky’s “A Week”, the tale of a week of Soviet rule and counter- revolutionary rising in a remote vil- lage, possessing all the quiet beauty of the classic Russian work, combined with a simplicity of form and a new vigour of “atmosphere,” which serves to drag one into the sweep of a great movement, transcending individuals and temporal events, yearrying one forward with it beyond the final page of the book into a new future. There are also the sketches included in the collection, “Flying Osip,” telling of | incidents of the revolution, which seem to have the burr and beat of machinery about them, while others | echo the hum of hurried voices ming- led with the click of a hundred type- writers —energy, creation, organisa- tion. There is the cold horror of the | “photographic” method of Semenov’s “Hunger”; the feeling of clumsy, pri-| mitive forces being slowly shaped and moulded in Zozulya’s “A Mere Trifle”; the charm and freshness of | liberated youth in Seifulina’s “Law-| breakers.” We should soon have also | in _ England — Gladkov’s “Cement,” which epitomises the giant creative forces of the revolution, building out of the ruins of civil war a new Russia. * * * Meanwhile, Russia’s old “intelli-| gentsia,” with its writers and artists, |divided and went different ways. | Some emigrated to Paris and Berlin | jor Prague. Others stayed in Russia, but shrank into themselves away | |from the new forces which they ab-| horred and could not understand. | Some of them, on the other hand, like | Count Alexei Tolstoy, Maxim Gorki,* | and Alexander Blok, were willing to} accept the new order, and tried to | understand it and interpret it in their art. The two former groups soon) tended to become barren, for the rea-| son that they had lost their social roots: great art can seldom gain in-, spiration for long from contemplation of one’s own shadow or admiration of one’s own reflection, These per- | Sons turned their attention inwards, |sought to escape from reality by in- roversion, and become neurotically itra-individualist and mystical. Many of the third group, however, vhile retaining the old forms and of- en casting their work in an individu- alist mould, managed to give a very | nteresting interpretation of the new| | forces and the new ideas. Because of | their previous training, they were able |to reach a higher perfection in form than newer writers among the work- ;ors, and their energies were less ab- sorbed in political and economic | tasks. As Trotsky says in his “Liter- ature and Revolution”:— i | “Tt is untrue that revolutionary art can be created only by workers. . . . It is not surprising that the contem. plative intelligentsia is able to give, and does give, a better artistic repro- duetion of the Revolution than the *Gorki’s latest book “Decadence, recently published in England by Cassell (7-6), is interesting as a pic- ture of the rise and decline of the Russian bourgeoisie over three gen- erations. . |Some of the new forms and rhythm | produced had particular interest. The proletariat, even though the re-crea tions of the intelligentsia are some- what off the line.” 4 Some of them, indeed, who had shared the workers’ experience in the days of civil war were able to inter- pret the emotions of ‘those days with power as well as perfection of form. For instance, in Veressaev’s “The Deadlock” (which is in an English translation) one feels the primitive force and creativeness of the Revolu- tion grappling cumbrously with the old order, brushing aside like flies the impotent theories and ideals of | BOOK R EVIEWS HISTORY ACCORDING TO VAN LOON. AMERICA. By Hendrik Van Loon. Boni & Liveright. Price $5. THE author of the latest “history” is one of those “popularizers” who have surfeited the market these past few years with what they imagine to be the knowl- dro of the ages, so simplified and condensed that one well-meaning “intelligentsia.” Thc conflict is here less impersonal thar \ in Libedinsky, and is shown as reflec. | ted in individual feeling and con | |flicts; but the spirit of the Revolu | tion is there, unadorned, gargantuai | and real. Some of this group, however, par | ticularly the younger among. them | reacting violently against the circum. | stances of their birth and the tradi | tions which had formerly held then in thrall,-sought in an ecstasy of re lease to out-revolutionize the revolu “| tion. They were anarchists in th: | cultural sphere: old forms, old tradi | tions must be scrapped and the clas sics must be banished to museums which these “Leftist” experiment ecstasy of breaking all ties with the past produced several works of high artistic value, such as those of the peasant poet Yessenin and the futur. ist Mayakovsky. But as Trotsky says of the futurists:— “Futurism carried the features of its social origin, bourgeois Bohemia, into the new stage of its development. A A Bohemian nihilism exists lin ‘the Futurist rejection of the past, but not a- proletarian ‘reyolutionism. We Marxists live in tradition, ‘and we have not stopped being revolu- tionists on account of it The | working class does not have to, and cannot, break with literary tradition. | because the working class is not in the grip of such tradition. The work- ing class does not know the old liter- ature, it still has to commune with it to master Pushkin to absorb him anu overcome him.” * * * Present-day art in Russia there- fore, transitional: like Russia’s eco. nomics it is at present a mixture of various streams. As the confusion of a transition period passes into the of the future, these various currents are likely to merge to form a Social- jist art. Meanwhile Communist criticism ex- ercises a selective’ judgment among this transitional variety. This it does by taking, not merely the usual cri- terion. as to perfection of form;’but also a judgment as to value as a con- stituent of a new art adapted to the new order. To judge art by this cri- terion is a recognition of the fact— a recognition possible onlv to the Marxist—that art isa product of so- cial conditions. Art. is the formula- tion of complex emotions in symbols, and it is successful to the extent that those symbols (be they sounds, color, lines or words) have sufficient gen- erality and similarity of appeal to awake a similar complex of emotions in the minds of others. (I. A. Rich- ards in his “Theory of Literary Cri- ticism” says that it evokes in the nervous system a complex of “atti- tudes” or incipient impulses to ac- tion). The deeper the layer (so to speak) of emotions which these sym- bols touch, and the fuller the gamut of emotions stimulated or released by art. it “systemmatises” emotions and gives them more harmonious and effective have had. Since emotions are the |result of experience, and the richest of them the product of social experi- ence, a new society, with new experi- ences and relationships, will require a new art. Sinc the new art, to ful- | fil its social function ‘and’ ‘to’ have value and permanence, must, there- fore, be adapted to the new society, one can judge a work of art from this point of view; and in this sense one can speak of a Socialist art and con- sciously help in its creation. * * . We in this country are still too cireumscribed by circumstance to pre- sent an alternative as yet to bour- geois art. Our efforts in this sphere are necessarily confined to political satire through the workers’ theatre movement, to songs and verses and cartoons. Isolated attempts of writ- ers, close to the proletariat, there may be to anticipate the future, and express the class sruggle in art, such as Toller’s plays and Martinet’s “Night.” Some may try to interpret the new Russia through the eyes of an observer, like Ralph Fox in “The People of the Steppes,” in which there lives the spirit of the Hast and of Bolshevism as a new leaven at work slowly transforming Asiatic Russia into something orderly and new, or Maurice Hindus’ “Broken Earth,” which mirrors the working of the new forces against the old in the Russian village. But not all which have a Socialist theme are nec- to lack form and quality, while some of it may be défeatist in spirit and not revolutionary, or a mere copy of bourgeois forms, with the hero re- versed. For the renaissance which will replace the decadence of bour- geois art-~its introvert — preciosity and tendency to mysticism, or its sheer commercial philistinism as seen in the cinema and the stage— we must wait till the bursting of the shackles of bourgeois society has un- loosed here as in Russia new creative spirit and new creative experience, MAURICE DOBB (Plebs, London) | | | completer, more homogeneous society | the symbol, the more powerful the) Art will have value in so tar as | expression than they would otherwise | essarily either literature or proletar- | ian; and much of what is thrown up| by our movement at present is bound, can know all that is worth nowing about anything by the imple expedient of reading one or two books. We thought Will urant with his falsification and vulgarization of the history of philosophy had reached the owest depths attainable in the o-ealled literary and historical ield, But Mr. Van Loon in his ook “America” has crawled ven beneath Durant. ie he From beginning to end the rork is a crude, smart-alecky ndeavor to reduce history to jazz. In the confines of 463 sages, printed large and pro- fusely illustrated, Van Loon YAN LOON. spans the centuries from the dawn of civilization to the year 1927. The great migra- tions of peoples were due to the fact that the younger generation suffered from the “wanderlust.” But there have always been “younger generations.” (Though, cur- iously enough, Van Loon implies that this phenomenon “the younger generation,” appears only occasionally.) We have them always with us. But we have not al- ways had hordes of people wandering upon the earth in search of places of settlement. The fact that des- ication of the land set in, driving the tribes of Central Asia forwar to the outposts of civilization is not known to Van Loon. He dismisses the ancient world in a few pages about Mediterranean civilization. The facts of economic ge- ography are unknown to him. As far as can be learned from Van Loon the ancient civilizations were pure ac- eidents. He doesn’t even mention the fact that they sprang up in the great river valleys of the Nile. the Euphrates, the Tigris and the Hwang-ho. These rivers do not even appear in his “map” of the old world. His treatment of subsequent history is equally as incompetent. To point. out all the errors contained would necessitate refutation of the whole book sentence by sentence. The crusades were not the result of the ereed of the christian flunderers for pelf, but to save the tomb of Christ and were caused by “the puritan Mohammedans.” Wher Van Loon discusses the Reformation he does not attribute it to the rise of the bourgeoisie, but to Calvin’s individual achievements. According to this “historian” Calvinism was not the religious reflex of a rising capitalist class, but was itself the motive force in history. Thus, on page 62 we read: “For if it be conceded that reasonable freedom | and happiness of the average individual is the goal | «:toward which all civilization is striving, then Calvin deserves a special and prominent niche in that hall of fame which every sensible man erects in some secret corner of his brain.” * * ° It is when he comes to his main topic, America, that his historical method is revealed in all its sublimity. Here, too, it was the great men and not social forces |that determined the course of history. His des i of Washington is played down to the underst any Babbitt or chairman of a kiwanis or ro Describing the attributes of Washington we are told: “All in all, a fine gentleman. Not the sort you'd slap on the back. No, not exactly. But if he de- | cided to go somewhere, you somehow or other de cided that you would go th’’.e too. Leadership, they called it. Well, he had it.” On page 92 and 93 we réad this piffle: “They were strong men of pronounced convictions. “They knew what they wanted, | “They were dead serious.” Van Loon is so ignorant of the geography of his own country that he imagines Massachusetts Bay is sur- rounded by “snow covered mountains.” Benjamin Frank- lin is depicted as a court jester, “the wit of the re- bellion.” aud. * . . On page 118 the author declares that he has read “through all the more popular volumes that have been published these last twenty years on the history of our country,” and all of them are inadequate. He alone has the correet system, He is a modest man! Every war in which the United States participated is misinterpreted by Van Loon in a fashion that would disgrace a high school boy were he to write such rot in an essay contest. It is when he comes to the close of his arduous his- terieal labors that Van Loon’s stupidity is positively delightful. The world war. is described as a great con+ flagration and the eminent. fire-chief, Mr. Woodrow Wilson, on April sixth of the year 1917 “called out the first of the engines. A few weeks later they made their appearance upon the soil of Europe. A few months later they were ready to start to work. . . . Within a very short time the walls of Germany and Austria began to crumble.” This noble act, extinguishing the fire in Europe, in- dicates our future destiny. No long are we isolated. We have a great historical missionfto perform and so the readers of Van Loon’s “history” are left with the admonition: “For our nation, our country, the fortunate strip of land which we call our own, by a strange: turn of fate has been called upon to be the guardian of mankind’s future.” Thus the “popularizer” of history, Van Loon, winds up his work with the dirty sermonizing of a pen valet of imperialism. He wants America to rule the world. It is an ambitious dream of empire that would make of the government of Wall Street a super-state, the ravager of all the earth. This filthy fawning before imperialism is the out- standing characteristic of this whole school of “popu- larizers.” Durant concludes his “Story of Philosophy” in the same servile vein when he says: “But we have become wealthy and wealth is the prelude to art... . We ate like youths suddenly disturbed and unbalanced, for a time, by the sudden growth and experience of puberty. But soon our maturity will come; our minds will catch up with our bodies, our culture with our possessions. Per- haps there are greater souls than Shakespeare's, greater minds that Plato’s, waiting to be born.” When we achieve the historical destiny depicted by Van Loon, then our benevolent ruling class can devote itself to developing new Shakespeares and Platos, to the satisfaction of Will Durant. How much lower can the lackeys of imperialism sink to gain the applause of their masters? —H. M. WICKS. FRUITS O¥ CLASS COLLABORATION. WRECKING THE LABOR BAN F Trade Union Educational L s. (Distributed thru the Wo shers, N. Y.) WA N the Exec the labor un judgment” shou banks and investment companies makes danger s. to trade union car have not given up the ve Council of the A. F. 3 opened lers of labor ion with the What did happen was the crash ¢ labor banks and investment companies the brot od of loc motive engineers which was exposed in all its rotten- ness at their last. convention. This not only meant a loss of about million dollars of the money of the workers in those trades y wrecked one of the strongest unions in the eount vs oT corruption of the leaders, the robbery of the treas the rifling of the insurance and pension money, all the vile pragtices of class coHaboration became known to the American labor movement, * * ars The membership, even tho noto: ly conservative “aristocrats of Labor,” were forced to rebel out in plain language in convention. 1 freely that not only were t engineers’ oned, but all the reactionary lieutenants the A. F. of L. became s: iously worried. This bomb-shell that exploded all the theories of cl laboration and make the whole practice so obv: ug to the membership. It proved every word of the warning made by the Left Wing in the unions and substantiated every charge of the Communists. Foster has put the facts together in most readable fashion just as they happened. It is a record so start- ling as to be almost unb vable. It is hard to imagine that the workers could h: been robbed so brazenly. Since 1920, banks and investment compan: grew to the enormous proportions of $150,000,000. The control of all this wealth lay in the hands of reactionary, un- scrupulous officials. How they stole these funds, how they saturated the membership with capitalist ideas, how they made policies that betrayed the workers, Foster tells us in this book. To what extent all this had gone, can be seen from a delegate’s expression at the conyven- tion that “You-stand here today confronted with a situa- tion that I do not believe a labor organization at any 7 1 WHEN 90 \ ( \ 2 MILLEN 7 time before this, in-all the history 6fthe ‘world, had te combat.” Another delegate likened the situation to the San Francisco earthquake. The temper of the delegates can easily be guessed from the fact that even A Grand Chief Engineer Edrington, who himself w: involved in the financial disasters, was forced to pl “I hope to see the day come when we can forget about investment companies, holding companies, realty com- panies—and get back to the old Brotherhood as a labor organization.” * * * Never was there such a presentation of the dangers of class collaboration. ‘This will do more than any other ten books on the theory of it. The book reads easily lt is extremely interesting, popular in style and damns the whole business of the “higher strategy of Labor” as it has never been damned before. If you want to de the trade union movement a service—put this book ir the hands of the men in your union. This is mental dynamite. This is a book that will start your brother members on some heayy thinking. —WALT CARMON, PERIODICALS. 'HE “New Masses,” in its December issue, lays off the dialectic and publishes instead two articles on the mine situations in Colorado and Pennsylvania—which is, as Oswald Garrison Villard would say,—a step in the right direction. * Altho Kristen Svanum’s “Colorado on Strike” is merely a chronicle of the events leading up to the Colo- rado walk-out, that and a colorful bit of reporting by Don Brown of a Pennsylvania mine town furnish the December issue with a certain stamina which the two or three preceding issues of the magazine have lacked. The issue contains nothing ‘startling but the mine stories, an,article by John Dos: Passos on the revolu- tionary theater. movement, an article on a southern mill town by Art Shields, and a story by Alice Passano Han- cock called “Escape” are all worth reading. —H, # COMMENT. nee cugrent issue (No. 64) of the INPRECOR (Inter- national Press Correspondence) is found a most in- teresting wealth of detail on the recent controversy in the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. It includes articles by J. Stalin, reviewing the history of the Opposi- tion and on the expulsion of Trotskv and Zinoviev by the Central Committee of the Russian Party. The Workers Library Publishers of New York have be- come sole American agents of this important publication which serves as a news and feature service to revolution. ary papers thruout the world. * * * * “Minor Music,” a volume of verse, by Henry Reich, Jr., will be published next Thursday, it is announeed. Reich is a frequent and popular contributor to .The DAILY WORKER and has written much notable postry, His poem on the death of Sacco and Vanzetti is. in- cluded in the “Sacco-Vanzetti Anthology” edited by Ralph Cheney and Lucia Trent. BOOKS RECEIVED—REVIEWED LATER. A Short History of Women. Davies. Viking Press. Venture: A Novel. By Max Eastman. Charles Boni. For Freedom: A Biographical Story of the Ameri- can Negro, By Arthur Huff Fauset. Franklin Publishing Co. The American Songbag. By Carl Sandburg. Har- court, Brace & Co, Standing Room Only: A Study of Population. By Edward Alsworth Ross. Century Co. Trader Horn. By Alfred Aloysius Horn & Ethel-- rada Lewis. With a foreword by John Gals worthy.—Simon and Schuster, By John Langdon- Albert &