The Daily Worker Newspaper, June 18, 1927, Page 8

You have reached the hourly page view limit. Unlock higher limit to our entire archive!

Subscribers enjoy higher page view limit, downloads, and exclusive features.

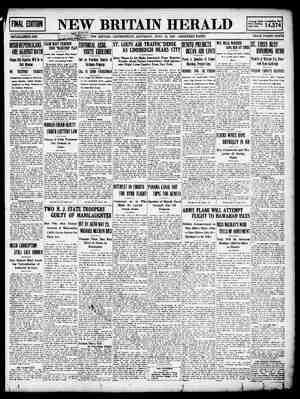

The Man Behind the Gun The Chinese Revolution The Significance of the Social Element - The opinion is often expressed in Social-Demo- eratic circles that the Chinese revolutien is purely & bourgeois movement. In refutation of this stand- woint, we may here cite some figures from Chinese, ron-Cormmunist sour:2s as to the profundity of the gocinl fermentation ameng the population. (Our sources in this connection are the publications of the “Chinese Government Bureau of Economic Infor- mation,” which publishes a weekly and a monthly report in English at Peking). The peasant organizations are rapidly increasing in number. At the beginning of March the number of organized peasants was as follows: (“Economic Bulletin” of March 2nd, 1927). Pe ae ee rs ree 1,100.000 Kwang i. Fe< die SW da KS RV ESD 50.000 Hunan 5 cheaien pebbavcaeeank 1,200,000 Hupeh Kiangsi Fukien 2,795,000 In many parts, where the work of organization is still in an initial stage, the membership figures eould not be ascertained. The returns for Fukien have been superseded. The number of organized farmers in these six provinces may without exag- geration be put at 3 millions. The efficiency of these peasant organizations is : depicted in a possibly exaggerated British report as follows: (“Times” of February 8th, 1927). “Immediately after the arrival of the Canton forces, Bolshevist agents started organizing peasant committees, which at present rule the entire province. They dictate the amount of the leases, and any landlord that offers resistance runs the risk of a sound thrashing. One land- owner was killed, the workmen’s union forcibly releasing the murderer, instituting an inquiry, and declaring the culprit to be innocent.” Other British reports (“Times” [Peking correspon- dent] of February 22nd, 1927) tell of fights between agricultural laborers and farmers; of the latter 60 are said to have been killed in the province of Kwangtung. “The peasants themselves now deter- mine the amount of the leases,” this report like- wise says, “and any farmer that contradicts them is cried down as an “imperialist.” One landowner was killed. The old system of ground lease has been abolished and new forms are being contemplated, it being intended that one tenth of the amount falls to the share of the peasant organization. We are informed, moreover, that the peasant or- ganizations “Red Lancers,” “Black Lancers,” and others, are armed and contributed not a little to the defeat of Wu Pei-fu. We need quote no further facts. The movement has all the characteristics of a peasant revolution, though, in contradistinction to former peasant re- volts, it is organized over a far wider area and is closely co-operating with the workers’ organizations. The trade union organizations of the workers reveal a similar rapid development. At Wuchang alone there were at the close of 1926 (as reported by the “Economic Bulletin,” of November 27th, 1926) no less than 80 trade union organizations with a membership ranging from 30 to 9,000. (Apparently the workers of each individual factory were at that time still organized separately). Altogether, there were in the town no less than 200,000 organized workers. At Shanghai the trade unions were, alter- nately, either outlawed or dominant in the town: in the latter cases the workers were armed. In March there were 108 trade union organizations with 287,- 042 members, (“Chinese Economie Bulletin” of April 2nd, 1927) without counting the seamen, dock workers, and business employes. The total prob- ably now exceeds 350,000. The following survey of the strike movement at Shanghai in 1926 deserves special interest. (From the “Chinese Economic Journal” of March 1927). In the course of the year there-were 169 strikes in 165 factories employing 202,297 workers. The longest strike lasted’84 days, which is tremendously long for Chinese conditions. In one factory there were 9, in one 8, and in one 7 strikes in the course of the year; in 4 factories the workers struck 5 times. In a single month there were more than 50,000 workers on strike. This shows the intensity of the movement. How heterogenous the movement, is, is demon- strated by the fact that the publication from which we quote enumerates no fewer than 71 different kinds of demands brought forward by the strikers. The most important of them were: ; Number of Cases Imerease of wageS..........:.. shea TRS 71 Re-employment of discharged workers... .35 Discharge or engagement of workers....26 Payment of wages for strike days...... +22 _ No discharge without adequate reason....24 Reduction or establishment of work-time. .18 In reading this whole list of demands, we cannot but be struck by the very great number of “solidar- ity” demands (such as for the release of arrested workers in 10 cases) and the sma!l proportion of demands for shorter working hours (only in 18 cases). The oppression of the workers is manifest by the fact that in 10 cases the demand put for- ward was for the abolition of corporal punishment! The outcome of the strike movement was as fol- lows: All demands refused........ Videwsskts ve oe Demands partially granted...............55 All demands granted. ............eee0e00+.27 Promise of investigation of claims.........18 EOGROGE osc tescetses bicsre thes nioeeekin @ In the towns in which the Canton government ruled, the labor movement was yet more extensive and successful. This is one of the main reasons why the British bourgeoisie is filled with such bitter ha- tred for the Chinese revolution; it lessens their profits. The reports in the British press reflect the fury of the British bourgeoisie. A report from Han- kow, e.g., says: (“Times” of February 22nd, 1927). * “All categories of workers, from the house- boy to the coolie, are being encouraged to de- mand more and more wages. The workers in the foreign enterprises now demand the 54-hour week, an annual bonus equal in amount to one month’s wages, and the settlement of all dis- putes by the trade unions. A large coal-mine, -with a capital of 1.5 million pounds, is now under the sole contro) of the miners’ trade aes union, which sells the daily output for the ac- count of its members.” “Strikes and demands for wage increases to quite an extravagant degree, are now the order of the day.” (“Times” of February 8th, 1927). “Business has truly been paralyzed by the ex- orbitant demands of the trade unions.” (‘‘Times” ‘of March 30th, 1927). “The demands of the trade unions under the Can- ton regime in China have become exaggerated, so that business is largely rendered impossible.” (“Times” of March 28rd, 1927). : There are innumerable reports of this “kind in the British press, all showing how deeply. the work- ing classes of China have been stirred up by the revolution. But not only peasants and workers, also the petty bourgeois circles have been affected. A special thorn in the eye of the British capitalists was the demands of the bank clerks. “It was reserved for the trade union of Chi- nese servants and employes in the foreign banks to present a list of demands to their employers which exceeds anything ever experienced. All these employes speak English or some other foreign language and are fairly well educated. The majority of them surely possess learning enough to know that there must be a limit to working expenses if business is to thrive. The demands in question range from 60 to 570 per cent increases of salary.” (“Times” of March 23, 1927). : In view of these demands, all the banks closed down. So says a report three days later. In reality, however, this step was taken for the purpose of dis- turbing economic life at Hankow by a sort of fi- nancial or credit blockade. The class struggle has penetrated far into the ranks of the petty bourgeoisie. “The chambers of commerce (organs of the great merchant class), on which the full weight of this campaign against property fell, have been substituted by commercial organizations founded on revolutionary lines (obviously re- tail traders’ organizations), while the members of the chambers of commerce are persecuted as traitors and money-grabbers.” (“Times” of Feb- ruary 22nd, 1927. The 450 millions of people in China are in a process of revolution. With the exception of the feuda] landowners and the military cliques, all classes of the population are taking part in this movement. By the treachery of Chiang Kai-shek, the bourgeoisie has separated itself from the revolu- tion and gone over to the camp of the counter- revolution. By acting thus, the bourgeoisie has also betrayed the anti-imperialist emancipation move- ment for it is impossible at the same time to fight against the proletariat and the general mass of ° the peasantry on the one hand and against the im- perialists on the other. The bourgeoisie has sur- rendered unconditionally to the imperialists. The situation may be said to be clearer now, inasmuch as China must either remain bourgeois under the yoke of the imperialists, or else become free under the jead of the proletariat and in opposition to the bourgeoisie. This state of affairs is a guarantee for the continuation of the revolution, even if a re- lapse sets in for the time being, Drawing by Jacob Burck - By E. VARGA